The South African

The South African

by Squadron Leader D.P Tidy

EDITOR'S NOTE:

Major Cornelius Arthur van Vliet, DFC

Cornelius Arthur van Vliet (known to the South African

Air Force as Corry) was born in Johannesburg on 27th

March, 1918. His parents had come to South Africa from

Holland at the turn of the century, and he was one of a

family of six, having two elder brothers and sisters, and a

younger sister. His junior schooling from 1925/30 was at

Yeoville Intermediate School, and he modestly confesses to

average performance both scholastically and in the sporting

field. His senior schooling was at the school which has

produced so many personalities of South African life,

Parktown Boys' High, Johannesburg. He was a prefect in

1935 and again, modestly, (modesty is Corry's middle name)

he says he 'made the 1st XV at rugby but never considered

myself much good. I was not very interested in cricket and

played tennis, and swam, as my summer sports.' He was a

student officer in the school cadet corps and 'very proud of

my 2nd Lieutenant's pip.' He took his duties seriously and

enjoyed the military atmosphere. In fact he very nearly

filled in the necessary enrolment forms to join the S.A.

Merchant Navy Academy, 'General Botha', at Simonstown

(which had earlier nurtured Sailor Malan, as described

in No.2 in this series in Vol.1, No.3).

Major C A van Vliet, DFC. In the background is a wrecked Me109

Then came a sudden void, as the Pupil Pilot Scheme did

not allow for training once a pupil had his 'wings', and few

articled clerks could afford private flying. After a few months

of flightless frustration he and a colleague from flying course,

Don Ord, felt they should do something about it. At that

time there were reports of air warfare in China, so they went

along to see the Chinese Consul in Johannesburg, but their

day-dreams were dashed on finding that they would have

to pay their passages to China out of their own pockets.

In any case, by then it was July 1939, and the war clouds

were gathering over Europe, and this kept alive their hopes

of real military flying. When Britain declared war on 3rd

September, 1939, Corry was quite annoyed that it took the

South African Government a few days to follow suit.

He was equally frustrated when, after numerous phone

calls, it took the Defence authorities about a fortnight to

call up the Reserve Officers. Looking back, however, Corry

admits that the SAAF mustered a fairly effective force in a

few weeks.

He had already had several training flights on the Hartebees

before September ended, with the emphasis on gunnery

and bombing. With 75 hours solo in his log book he was

'ready to take on the whole of the Luftwaffe', he recalls

wryly. He was posted to No 2 Bomber Fighter Squadron at

Waterkloof Air Station under Captain J. A. de Vos, flying

the Hartebees (which was, of course, the South African-built Hart).

He enjoyed the next seven months from a flying-training

point of view, but found them frustrating in that there were

no signs of moving to an operational theatre. The highlight

of this period was his being allowed to fly the only Fairey

Battle (K9402) in South Africa; in fact the only modern

bomber in the SAAF.

On 6th May 1940 he was posted to No 11 Bomber Squadron

under Major R. H. (Bob) Preller and shortly afterwards

received the news that the Squadron was 'going North'. By

that time Italy was obviously coming into the war and, with

her military presence in Abyssinia, prospects looked bright

for some real action.

The next few days and nights were a hectic scramble for

spray guns, and grey, green and brown camouflage paint.

Each pilot had a mechanic allocated, and worked with him

as a team responsible for getting their particular Hartebees

ready for the trip.

On 19th May 1940, No 11 Squadron left Waterkloof Air

Station with 24 Hartebees, the first to fly north as a unit

with its own aircraft ready for battle. Girl friends, wives

and families were allowed entry to the station to say farewell.

With a large number of aircraft flying as one formation

(apart from an advance flight of three), the hops were short

and the route was:

When he got to Nairobi he had 'the magnificent total of

167 hours' flying'. At one minute past midnight on 11th

June Italy declared war. At 0800 No 12 Squadron's converted

Junkers 86s set out from Eastleigh on the first bombing

raid on the enemy.

Corry's first raid was flying one of three Hartebees on

16th June. The target was supposed to be Mega, but he still

has his doubts that the leader found the correct target 'but

it was good fun dropping real bombs on real buildings'. His

operations at that stage were short-lived however, for on

21st June 1940 some of the Squadron were sent back to

South Africa to fly up the Fairey Battles with which the

Squadron was to be equipped, the Hartebees being taken

over by No 40 Army Co-operation Squadron under Major

J. T. (Jimmy) Durrant (later Major-General, CB, DFC and

OC 231 Heavy Bomber Group, RAF, and post-war Director

General SAAF with rank of Brigadier, the highest rank in

the SAAF at that time). The Battles could only carry

1000 lbs of bombs for 1000 miles at 240 m.p.h. On 7th

August 1940 Corry flew one back to Nairobi and, by 12th

August, the Squadron had re-formed and was stationed at

Archer's Post, a bush aerodrome about 40 miles north of

Mount Kenya on the fringe of the North West Frontier

District, fifteen Battles being assembled there. The 'aerodrome'

was notable at that time as a landing strip used by

Martin Johnson, a well-known big game hunter and photographer.

It was actually only a clearing in the bush.

In taxying out for take off on 17th August 1940 to go to

Wajir for an overnight stop, Corry burst a tail-wheel tyre

and was an hour behind the others. At that stage he had

done no night flying, and had to find Wajir in the moonlight

and land by the light of a few army trucks placed in a

line. He made a good landing but, when taxying back, fell

into a bomb crater made that afternoon by Capronis which

had bombed Wajir. Luckily he suffered no damage and was

later pulled out.

Next day, 18th August, the first flight of four Battles

under Major Preller (of which Corry's was one), failed to

reach the target, Mogadishu, owing to adverse weather

conditions, and struck at Merka instead, damaging a

Caproni and administrative buildings.

On 21st August 1940, Corry flew on a raid against

Mogadishu once again. The drill was to take off from

Archer's Post and fly to Habaswein, a long stretch of semi-desert

which was a natural landing ground.

During a low-level pass over Mogadishu, Corry's aircraft

was hit by machine-gun fire and Lt W. J. B. Chapman, the

Squadron Armament Officer, 'who had come along for the

ride', says Corry, was wounded in the leg. As he was bleeding

fairly badly, Corry got back to Habaswein and procured

medical attention for him as soon as possible. James Ambrose

Brown, in 'A Gathering of Eagles' (Purnell) says: 'The

Squadron's photographer being in Nairobi with the photographs

taken on 19th August, Lt W. J. B. Chapman,

familiar with the F24 camera, volunteered to act as photographer.

He took the initial photographs but, after being

wounded during the third bombing dive and unable to

stand to operate the hand-held camera, he instructed Air

Sergeant Wright how to use the camera and they brought

back useful photographs'. Three aircraft were destroyed,

six seriously damaged, five hangars damaged and the

covering of a petrol store destroyed. One rear-gunner

claimed three mobile kitchens and the Italians confirmed

destruction of five Capronis, according to Brown (ibid).

Having been in the accountancy field, Corry was made

bar officer which had its advantages, with regular trips to

Nairobi to keep the bar stocked. On 7th September he took

part in another raid on Mogadishu, the targets being aircraft

and a 'motor transport yard'. During one of the

bombing runs he suddenly found an Italian Romeo 37 (a

reconnaissance aircraft the Italians were obliged to use as a

fighter) just ahead of him. Unfortunately the Fairey Battle

had only one forward firing gun which jammed after a few

rounds had been fired. Major Preller wrote later of this

target:

'The big joke was that the collection of vehicles (Corry's

"motor transport yard") was a collection of ancient derelict

vehicles abandoned since the Abyssinian war' (Brown ibid).

On 12th September 1940 (at the height of the Battle of

Britain over far-distant England), Corry was led by Captain

J. R. de Wet, in company with Lieuts E. G. Armstrong and

J. E. Lindsay on the other two Battles. Brown (ibid) reports

'The Italians had also learned from experience that the

South Africans attacked at three-day intervals'. They were

ready with fighters when No 11 Squadron returned to

Shashamanna on 12th September. Three Fairey Battles

made low-level and dive attacks, scoring a direct hit on the

headquarters building with a salvo of 250 lb bombs, destroying

one Savoia and seriously damaging another. Four

CR 32s engaged the Battles, one of which crashed in flames,

killing Lt E. G. Armstrong and A/Sgt C. C. Adams.

The fourth Battle, flown by Lt J. E. Lindsay, had orders

to take photographic evidence of the bombing, says Brown,

and 'turned back for its base at about 2000 feet. Warrant

Officer Marescal Gobbo (a veteran of the Spanish Civil

War) came out of the clouds below. Before Air Gunner

V. P. McVicar could get in a burst, he had opened fire,

wounding McVicar and Air Sergeant L. A. Feinberg, the

photographer. The aircraft caught fire. Lt J. E. Lindsay

put the Battle down in a small opening between trees. As it

landed it struck and killed a villager and burst into flames.

The escaping crew were set upon by armed natives and

would probably have been killed had not the Battle's

ammunition begun to explode. The villagers fled and the

Italians, arriving on the scene, took the airmen into captivity,

the wounded being flown to Addis Ababa for treatment'.

This, says Corry, was the first time it really dawned on

him that in a war, bullets went both ways. (Louis Feinberg

survived and lives in Johannesburg and we often meet for a

chat about old times.-AUTHOR).

Months after the crash, a propeller blade from the crashed

Battle was found among the Shashamanna graves, with a

fence round the wreck of the aircraft, a cactus plant at each

corner, writes Brown (ibid). On the metal of the propeller

was engraved: 'Luggotente (sic) E. G. Armstrong 11

Squadrone Bombardamento, SAAF 12.9.40.'

On 14th October 1940, Captain J. de Wet led Corry and

Lt Hamilton on a bombing raid on the aerodrome at the

western town of Jimma. Corry destroyed a Caproni, but

when re-forming, the formation was attacked by two

CR 42s; they took cover in some very welcome cloud. The

three Battles were in formation and heading, Corry thought,

for home. Brown writes (ibid), 'The controls of Captain de

Wet's aircraft were badly damaged by a CR 42, and a

burst of anti-aircraft fire put the instruments out of action.'

Corry recalls that it was the custom in those days 'to set

the compass for the course to the target, and on returning

to merely steer the reciprocal, i.e. red on red to the target,

and red on black for home. It was all pilot navigation and

no luxuries such as radio, or even oxygen. Suddenly Lt

Hamilton waggled his wings violently and broke away from

the formation. I thought he still had a bomb left and had

gone to drop it as we didn't worry overmuch to stay in

formation, and raids were semi-individual affairs. After

formating on Jannie de Wet for about 45 minutes, I happened

to take a more serious look at my compass and was amazed

to see it was red on red and not red on black! I immediately

closed my formation position with Jannie and made violent

arm signals for him to turn back (no radio), but he didn't

understand my signals. I was on the point of turning back

myself when a large river showed up ahead of us. Navigation

at that time was a matter of map reading and compass

and Jannie realised we had got to the Blue Nile - in fact

we weren't very far away from Addis Ababa!

'He waved me forward to lead and I immediately turned

180 degrees for home. On a rough calculation I knew we would be

lucky to get out of enemy territory, and fuel economy was

vital. I climbed to 21 000 feet which I felt was the maximum

we could risk as we were not fitted with oxygen, and throttled

back to minimum cruising revs. By this time I had been in

the air for about six hours and badly needed relieving. This

was achieved with the aid of an empty Verey cartridge shell

which I normally used as an ashtray. After that incident

the perspex covering never lost its stains.

'I was making for a landing strip at Lodwar as I was not

aware of one at Lokitaung at the north end of Lake Rudolf

Jannie knew of the existence of Lokitaung and, when he

broke away to land, I thought he was out of fuel. I knew I

wouldn't make Lodwar with my fuel but thought it best to

get as far as possible. Being a semi-desert area, I felt I had a

good chance of doing a dead engine forced landing and

decided to fly to the last drop of fuel. I am still amazed how

I missed all the boulders when I finally had to land. From

21 000 feet the ground looked like one big areodrome, but

at 500 feet you see all sorts of unpleasant things especially

when you have a dead engine and no chance of going round

again! Anyway, my luck held, and I did a successful wheels

down landing. Air Sergeant Wright (my gunner), and I,

collected the canisters of water and iron rations, and started

our hike to Lodwar some 60 miles away. I had seen a road

track from the air which we reached fairly soon. We walked

until some time after dark when we saw car lights in the

distance. I was fairly sure we were out of enemy territory,

and waved the vehicle to stop. It was an army vehicle going

to Lokitaung. We got there to find Jannie de Wet had

crash-landed as the fighters at Shashamanna had damaged his

elevator controls (he had landed using only elevator trimming

tabs.-AUTHOR).

'The following day we returned to my aircraft with some

fuel and I carried on to Lodwar for a proper re-fuel. The

total time in the air was 7 hours 40 minutes which I think

remained the record on the Squadron with the normal fuel

capacity, without special tanks.

'An interesting side issue was that Lt Hamilton got back

to base and told Major Preller he had left me flying on the

wrong course. Major Preller predicted correctly that, when

we reached the Blue Nile, we would realise our mistake and

turn back, and also predicted almost exactly where we

would finally force land.'

After a few more routine jobs without incident Corry was

sent to Lokitaung to carry out an offensive reconnaissance

for the King's African Rifle Regiment stationed there. He

recalls: 'I had a full bomb load of small anti-personnel

bombs in containers, which meant that they were instantly

live when they left the container, and therefore were not a

very pleasant load with which to carry out a forced

landing - especially a belly landing!

'I took off from Lokitaung with Air Sergeants L. Lamont

and E. Murphy as rear-gunner and observer. We flew at a

fair height above what appeared to be a military encampment

of sorts, but at that height I couldn't observe any particular

activity or detail, and so made a low-level pass over the area.

Too late I realised that there were machine-gun nests on

either side of me and I collected a shot in the glycol radiator.

My pass over the encampment was fortunately in the direction

of home so I continued flying low and straight ahead

with white smoke pouring out. I considered I probably had

about five minutes of flying before my engine packed up.

With mixed feelings of trying to get as far as possible but

yet not wanting a forced landing with a probably white-hot

engine, and still lots of petrol around, I decided to get a

little more height. I also still had to make a decision about a

belly landing with a full bomb load, as I certainly would

never make the necessary height to jettison the bombs.

'The area was fairly level with scrub bush, and as the

temperature gauge left the clock, I let the wheels down and

took a chance on what lay straight ahead. Just before landing

we saw hostile Merille tribesmen ahead. They were the

Italian mercenary counterparts of the Turkana tribes

supported by us. The Merille in particular had a reputation

for performing certain anatomical operations on their

victims, and certainly would not have been very partial to

us in view of prior bombing raids.

'As we touched ground, the left wheel hit a bump. The

wheel was torn off, hit the tail of the aircraft and came

bounding forward past my head. The aircraft slid along on

its belly on a dry mud swamp, and we held our breath,

hoping the bombs wouldn't explode. Our luck held, and we

scrambled out to see smoke coming from the engine. We

quickly collected two water containers holding about 2,5

gallons but, fearing that flames might burst from the engine

at any moment, we did not wait to collect food. I took my

rifle.

'We cracked a hole in the internal fuel tank (with the axe

carried on board) before leaving, and heaped our maps and

other documents in the cabin. I fired a Verey pistol into it

and the machine blazed up.

'We cleared off for all we were worth, covering more than

half a mile before we looked back, when we saw a mushroom-shaped

column of smoke 50 feet high and heard the rumble

of explosions. We made for a hill, knowing that the Merille

tribesmen would easily track us across the soft, dried mud

of the swamp. After an hour's walking and running we

crossed the border. Later we saw a lorry approaching. A

small advance party of one officer and two Askaris came

forward and our anxiety about their identity was dispelled,

for they were friends. They had seen us come down and had

come forward to rescue us.

The next three months were occupied bombing enemy airfields and supporting the army advance which was putting the Italians to flight. By March 1941 the Squadron was based near Mogadishu, where the former CO, now Lt-Col Preller, was at Wing HQ. He wanted to get a captured Italian Caproni 133 bomber down to South Africa, and it was Corry and Captain Meaker who flew it down after heroic efforts to make it serviceable. The three-engined monoplane was the first captured aircraft to be seen in South African skies and Mrs Smuts, wife of General J. C. Smuts, the Prime Minister, flew with Corry around Pretoria with her family in the aircraft. He relates:

'The Caproni had a form of stable door on the port side at the rear. The top half when open allowed for a machine gun. I was horrified during a left turn over the city to see all the children (four of the Smuts grandchildren and Mrs Smuts's daughter, Mrs J. H. Coaten, were in the aircraft with Mrs Smuts.-AUTHOR) leaning over the top of the door to get a better view. I hurriedly changed the left hand circuit to a right hand, with visions of scattering the Prime Minister's grandchildren all over Pretoria.'

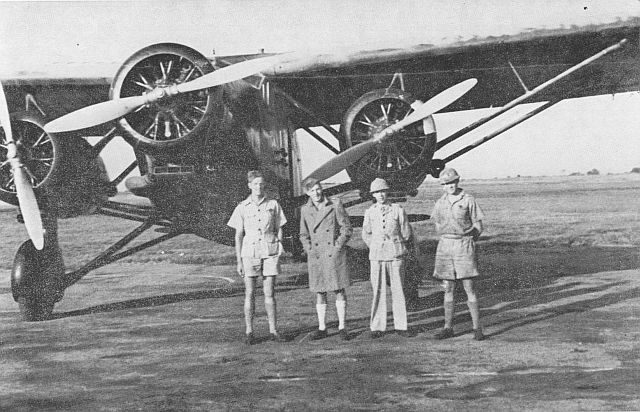

The captured Italian Caproni CA133

at Broken Hill on the flight to South Africa, 27 March 1941.

The crew (left to right)

Lt C A van V, Capt J Meaker,

A?Sgt Knottenbelt and WOII Botma

In the combat above Halfaya Pass on 24th September

1941 (reported in detail in No 8), Corry was shot down,

after being attacked by three Bf 109s which shot away his

controls. He baled out and landed safely, but injured his

shoulder, but then he was lucky because he was picked up

by our forward troops. He was sent to Mersa Matruh for

medical treatment and, as soon as he could (after three days),

he rejoined the Squadron with his arm in a sling, and walked

into the Mess to a rousing cheer, looking much his old self.

He was out of action for most of October owing to the

shoulder damage, but on 4th December 1941 he led 10

Hurricane MIs as top cover for No 274 Squadron, Royal Air

Force, in the Bir el Gubi/Gabr Saleh area. Eight enemy

aircraft were seen in a gaggle (i.e. in no particular formation).

No I Squadron's ten Hurricanes were flying in pairs,

line abreast, a formation which had shortly before taken

the place of the former vic.

Corry climbed in a left hand turn to meet the MC 202s

and the final score in the encounter was two Macchis

destroyed, three probably destroyed and three damaged.

Next day, again with No 274 Squadron, RAF, Corry led

his formation of 10 Hurricanes to the west, turning north on

spotting a MC 202 which dived in the rear of the formation.

At the same time his formation was attacked by several

aircraft which dived out of the sun. In the mix-up which

followed one Bf 109F was claimed as a probable, three

damaged and a MC 202 damaged.

On 17th December 1941 only eight Hurricanes could be

mustered by No 1 Squadron SAAF, to provide a close escort

to five Blenheims of No 84 Squadron RAF and three of

No 14 Squadron RAF, bombing Derna. Coming back, 12

miles south-east of the target, 12 Bf 109s attacked the formation

of eight Hurricanes and eight Blenheims. Corry, leading

the escort, saw two of the Messerschmitts, for no apparent

reason, fly right across the front of the Blenheims. Without

altering course he was able to open fire from a range of

50 yards, and one of the Bf 109s pulled away and burst into

flames. Corry saw the tail weavers drawn away from the

formation, and fall back to protect the rear. He fired a short

burst at a 109 which pulled out of an attack on a Hurricane,

but Corry observed no effect of his fire. He saw two Hurricanes

hit the ground and flame, and also two Bf 109s.

Captain Voss reported that two Bf 109s shadowed the

formation all the way back to Gazala. Near the airstrip one

of them dived from 3000 feet, then levelled out and began

an attack on the Blenheims. The 109 opened fire on the rear

bomber at a range of 100 yards, but did no damage, as

Corry got in a full-deflection burst on him at only 50 yards,

and forced him to pull out in a climbing turn, and break

off the engagement. This was the only attack made on the

Blenheims, the Messerschmitts having made many attacks

on the Hurricanes, apparently intending to draw them

away from the bombers. Although no Blenheim was

damaged, four Hurricanes were lost, three pilots killed, and

two Hurricanes, (one of them being Corry's), very badly

damaged by cannon fire. For the remainder of December

1941 and early January 1942, heavy rains made the landing

ground unserviceable. On New Year's Day came news that

Corry had been Mentioned in Dispatches for his work with

No 11 Squadron in Kenya, and on 7th he was awarded

the DFC for his flying with No 1 Squadron, SAAF, the

citation being carried in the Government Gazette for 20th

January 1942. A suitable party followed, as Benny Osler's

DFC was announced in the same Gazette.

The end of January saw a general withdrawal as the

Germans pushed back the Allied forces in the desert. In the

afternoon of 5th February 1942, Corry led four Hurricanes

on a strafe of the coastal road north of Tmimi. Leading the

aircraft out to sea, he crossed the coast a mile north of his

target, and completely surprised motor transport and gun

posts along the road, and the run was almost complete

before army guns opened up. Two lorries were set on fire,

two more damaged and several gun-posts were attacked.

By now he had flown 144 operational sorties, and had 355

operational and 261 non-operational hours, and was ready

for a break when he was ordered back to South Africa,

arriving on 19th March, 1942 for a month's leave. He spent

seven months with No 10 Squadron SAAF in Durban,

flying Mohawks and Kittyhawks and also flew a captured

Italian CR 42. He recalls that the most exciting moments of

those months were flying a Kittyhawk as target for searchlight

practice.

In December 1942 he was promoted to Major and

formed No 3 Squadron, sailing from Durban in the Nieuw

Amsterdam (as I had in March-AUTHOR), and finished up

in Aden training new pilots.

He found this rather boring and managed a transfer to

No 7 Squadron SAAF in the Western Desert. The Squadron

was equipped with Hurricane IIDs (Tank Busters) fitted

with 2 x 40mm cannons. He spent April 1943 training

against ground targets, but the IIDs were withdrawn and

the Squadron re-equipped with IICs, so he never flew the

IID on operations.

May to July 1943 saw Corry mainly in the Derna area,

doing a few patrols over convoys, but there were no engagements

with enemy aircraft. The only highlight of this period

was operation 'Thesis' on 23rd July 1943 (in which my

Squadron, No 74 (F) RAF also took part.-AUTHOR). Over

100 aircraft attacked various targets in Crete. It involved

over an hour right down on the sea to avoid early warning

to the enemy, and there was heavy flak over the island.

In August 1943 No 7 Squadron was re-equipped with

Spitfire Vcs and stationed at St Jean in Palestine. Soon after

it moved to Gamil Landing Ground at Port Said. The buildup

for the Kos episode (reported in detail in my article

'Dodecanese Disaster', in Vol 1, No 2.-AUTHOR) began

and the Squadron went to Antimachia on Kos.

After Kos, at the end of October 1943, No 7 Squadron

was stationed at Savoia in Italy, and Corry handed over to

Major Stanford and took over No 4 Squadron at Palaba

near Foggia. November and December 1943 were fairly

active on fighter/bomber sorties and ground strafing enemy

transport. Some of the sorties were over the Adriatic into

Yugoslavia, attacking trains and road transport. Although

the enemy never showed up in the sky, the flak and ground

fire were intense and No 4 suffered quite heavy losses.

Corry thinks that this and delayed nervous reaction from

Kos had their effect. He had logged 180 operational sorties

and had 419 operational hours and 406 non-operational

by then.

The Squadron Doctor told him he should leave the

operational sphere as he was worn out after the strain of

these campaigns, and he returned to South Africa in 1944.

With his usual total modesty he says: 'One feels a little

crushed and subdued to feel one had to drop out but I

think, on statistical averages, I had been very lucky to last

as long as I did.' He had no need to feel crushed; he had

done more than most, and should feel great pride that he

had lasted so long. Rob McDougall, who was with him on

Kos, told me recently, 'Corry is the bravest man I know',

and Rob knew many.

From March 1944 to December 1944 he was Chief Flying

Instructor at 10 Operational Training Unit at Waterkloof

Air Station, and during this year on 8th June he received a

second Mention in Dispatches for his part in the Kos

operations.

In January 1945 he was posted to England with Major

L. B. van der Spuy for the Central Gunnery School course

at Catfoss in Yorkshire, and the Fighter Leader School

course at Tangmere in Sussex. He achieved a distinguished

pass, the gunnery being done on Spitfire Vcs and the FLS

course on Typhoons and Tempests.

He recalls: 'I was essentially a single-engine pilot but was

foolish enough to accept the offer to fly a Mosquito. Swinging

on take-off, I still don't know to this day how I pulled

it over the line-up of parked aircraft and the hangar behind.'

He also flew the jet Meteor in 1945 which was a novelty at

that time. From Harts and Wapitis to Meteors in six years

was quite a contrast!

During the FLS course at Tangmerc, VE (Victory in

Europe) Day was celebrated and shortly after, Douglas

Bader, the famous legless fighter leader, became the operational

instructor.

Corry returned to South Africa and, during August 1945,

there were some possibilities of operations in the Far East

but September brought Victory in Japan (VJ) Day and

peace, and Corry's thoughts turned to civilian life. October to

December 1945 saw him in charge of N'changa (Northern

Rhodesia), a refuelling point for the shuttle service bringing

troops home from Cairo. He had an Anson for his

personal use at this time to enable him to visit various

radio stations in the area.

In January 1946 he returned to South Africa and went

down with a severe attack of malaria. The nurses told him

afterwards that it was just about 'tickets'. March saw Corry

return to his old firm to finish his Chartered Accountancy

Examinations.

He returned to flying to do a short refresher course at

Waterkloof in August 1948 and had some hours on a

Spitfire IX which he had been very keen to fly on operations

years earlier, but had been confined to Vcs. He also got

some flying with the City of Johannesburg SAAF Reserve

Squadron at Baragwanath during 1948/49 with a farewell

beat-up of Virginia Farm Golf Course on 15th October 1949.

(He reports wryly that the police wanted to prosecute for this

beat-up!). Since that day he has not touched the controls,

and he went to Rhodesia at the end of 1949 and is now the

Chief Financial Executive of the Cold Storage Commission

of Rhodesia which handles almost the entire beef trade in

Rhodesia. He remains as quiet, modest and charming as

ever; one of the most efficient and gallant of the South

African Air Force pilots of World War II. It was only with

great difficulty that I persuaded him recently, when he was

on a rare visit to South Africa, to let me write this. He

claimed that he was of no importance and still does so, but

it was such as he that made the SAAF a household word

for steadfast and brave service.

(The Author would like to record his sincere thanks for Major van Vliet's kindness and courtesy in filling gaps by his personal reminiscences in conversation and by letter).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org