The South African

The South African

by Colonel F.E. Wagonaer

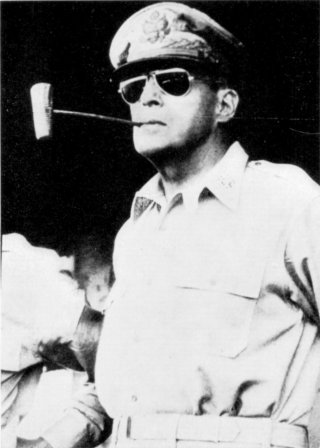

A characteristic study of U.S.

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur,

Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces

in South-west Pacific as he heads for Luzon

on January 9, 1945 to lead troops personally

in the initial landings.

“I am closing my 52 years of military service. When I joined the Army even before the turn of the century, it was the fulfilment of all my boyish hopes and dreams. The world has turned over many times since I took the oath on the Plain at West Point, and the hopes and dreams have long since vanished. But I still remember the refrain of one of the most popular barrack ballads of that day which proclaimed most proudly that:

“And like the old soldier of that ballad, I now close my military career and just fade away — an old soldier who tried to do his duty as God gave him the light to see that duty.

“Goodbye.”

General of the Army, Douglas MacArthur, spoke these words before a packed joint session of Congress in Washington on 19 August 1951, eight days after President Harry Truman announced his release from command in the Far East. After being ticker-taped in practically all the major cities across the U.S., MacArthur did in fact “fade away” for the remaining 13 years of his life — to serve as the Board Chairman for Remington Rand, and write his Reminiscences, which he completed only a month before he died. He had served in the Army for 52 years 33 years as a general — winning every decoration in our showcase. Starting from the top in priority and working down: Medal of Honor; three Distinguished Service Crosses; four Distinguished Service Medals; seven Silver Stars; two Purple Hearts; the Distinguished Flying Cross; Bronze Star Medal; and the Air Medal plus dozens of foreign decorations.

And so ended one of the longest and certainly most illustrious military careers in the history of the U.S. Where MacArthur ranks in relation to Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar, Napoleon and all the others is something the historians will have to decide after poring over documents not yet available. For while illustrious, a soldier-statesman of the first order, MacArthur made mistakes (only one of which he ever admitted - his first marriage ended in divorce - and which gets but two lines in his Reminiscences. The poor girl’s name is not even mentioned). There are shades of gray in the controversy over MacArthur which scholars will have to sort out people still alive who are not talking; files not yet released. Pompous, blustery, imperious, a dangerous militarist, egotist, glory-hunter, theatrical to the point of hamminess these are some of the words used by those who hated him. For those who adored him and considered him almost a demi-god a patriot, brilliant strategist, tactician, bravest of the brave. Such words colour objective analysis. He comes across with soldierly virtues somewhat more notable in the classic ages than our own - strict honourableness, belief in the right, moral integrity, dedication to an ideal (do you really think he might be distantly related to King Arthur ?). However you take him, there is one facet about which almost everyone would agree — you feel his presence whether you watch him with your eyes or just listen to his voice. As one of the junior officers on his staff said: “He’s the only man in the world who could walk into a room of drunks and all would be stone sober within five minutes."

Certainly in the short space of time allotted to me tonight, I am in no position to review all the details of his life and campaigns. What I can do, however, is search for the highlights, those events and personalities that, in my view, must certainly have had an impact on his life and decisions. Whether these decisions were brilliant or not I leave to the scholars. One of MacArthur’s biggest personal mistakes was that he dared to upstage the President, his Commander-in-Chief. He exceeded the bounds of a soldier by challenging a political head on political matters. He did the unsoldierly thing by violating the chain-of-command, and for this he was sacked. But was it a mistake? MacArthur lived by the West Point creed: “Duty, Honor, Country.” What represents a country? — a flag, a Congress, a President? Robert E. Lee said that country was Virginia, even though he had sworn allegiance to the U.S.A.

How does a soldier do his duty? blind obedience? Can a soldier’s duty be to challenge a politician on political matters? The drama of MacArthur’s remarkable career leading to Korea April 1951 is full. In all humility I can touch but a fragment of it tonight.

I feel that it is to his father that we must turn for our first impressions. In 1862, 17-year-old Arthur MacArthur left Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to go off to war as the Adjutant, 24th Wisconsin Regiment, Union Army. A year later, General Phil Sheridan was personally to bestow on him our highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for carrying the regimental colours to the top of Missionary Ridge - after three other bearers had fallen and the Regiment had wavered. A year later, Arthur was the colonel of his Regiment - the boy colonel, at the tender age of 19, the youngest regimental commander in the Union Army. After the Battle of Franklin in November 1864, a regimental officer wrote this about his boy colonel:

“There was no time to form lines. We just rushed pell-mell to meet the enemy in a desperate hand-to-hand mêlée. I saw the colonel sabering his way toward the leading Confederate flag. His horse was shot from under him, a bullet ripped open his right shoulder, but on foot he fought his way forward trying to bring down those stars and bars. A Confederate major now had the flag and shot the colonel through the breast. I thought he was down for good but he staggered up and drove his sword through his adversary’s body. But even as the Confederate fell he shot our colonel down for good with a bullet through the knee.”

Arthur MacArthur went on in the Regular Army — through a series of Indian posts, through the Philippine insurrection as the Army Commander and Military Governor to the rank of Lieutenant General, senior officer in the Army, from which rank he retired. But even in death, in 1912, at the age of 67, he became an Army legend. His old regiment, the 24th Wisconsin, was holding its 50th and last reunion in Milwaukee. Arthur MacArthur was the toastmaster. He got to his feet, began recalling the old days — to the top of Missionary Ridge, closing the gap at Franklin. “Our indomitable Regiment . . . , he said and his voice faltered. His face grew ashen white. The old Regimental Surgeon rushed to his side. “Comrades the General is dying”, he said simply. That’s a pretty hard act to follow.

Douglas MacArthur was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, 26 January 1880. His young life was spent in a series of Indian posts in Texas, New Mexico and Kansas. In 1884, his father was assigned to Ft Selden, New Mexico. From his Reminiscences:

“Company K with its two officers, its Assistant Surgeon and 46 enlisted men comprised the lonely garrison, sheltered in single-storey, flat-roofed adobe buildings. It was here I learned to ride and shoot even before I could read and write indeed, almost before I could walk and talk. Our teaching included not only the simple rudiments but above all else a sense of obligation. We were told to do what was right no matter what the personal sacrifice may be. Our country was always to come first. Two things we must never do: never lie; never tattle.”

What can be drawn from this? Throughout his speeches and writings, he goes back to his experiences on the frontier - even though one wonders how much was pure romanticism. Be that as it may, there is no doubt that MacArthur knew that he had been born in the purple (or khaki as we’d say today), and most important, that he was determined to live up to it. The heritage of his Father must have had a tremendous impact. Years later, MacArthur was to tell a friend in Tokyo: “When I perform a mission and I think I have done it well, I feel that I must stand up squarely to my Dad and ask: ‘How about it, Governor?’

It was only natural that MacArthur should go to the Military Academy at West Point. What was not natural was that he should do so well. He graduated in 1903, first man in his class, having recorded the highest scholastic record in 25 years. He was also the First Captain of the Corps — the senior cadet in rank — and he won his letter in baseball. He had passed the first test in following his Father’s act. What he needed now was a war and a little luck. He got both.

April 1917, when Congress declared war on Germany, found Maj. MacArthur as the youngest of 30 officers on the Army General Staff, Military Assistant to the Secretary of War and specifically responsible for liaison between the War Department and the Press. Many things happened to brighten his star. I shall mention only one:

A staff study was circulated among the General Staff proposing that the first troops in France should be the Regular Army — a rather normal proposal. MacArthur disagreed with the conclusions — apparently the only one to do so — saying that to get the country behind the war effort, one of the first divisions across should be composed of State National Guard Units (civilians), gathered together from all across the land like a “Rainbow”. He was called upon personally to defend his ideas before President Wilson. His ideas won, and the 42nd Rainbow Division was born (Mac’s brainchild). MacArthur went on the books as someone to watch.

When the Rainbow Division was formed, MacArthur became its Chief of Staff as a Colonel skipping completely the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. With the Division in France, he was no rear headquarters staff officer — there were too many medals to be won. He won his first one, a Silver Star, as a volunteer accompanying a French party in a raid on the German lines. He was soon promoted to Brigadier General and given a brigade. Five days before the end of the war, he was given command of the “Rainbow”, but his promotion to Major General never went through because of the Armistice. No matter, he had made his mark — the most decorated general of the war with an accolade penned by the Secretary of War himself: “The greatest front-line general of the war.” At the age of 38, he could for the first time square up to his Dad and ask: “Governor, how about it?”

Colonel Douglas MacArthur is decorated with

the

Distinguished Service Cross

for Bravery by General John J. Pershing

With acknowledgements to International News Photos

Several things began to show in 1917-18 in addition to his tactical brilliance and physical courage.

He knew that a good commander needs to be not only an able manager and courageous but also a figurehead up to whom the troops can look with interest and admiration. MacArthur began to cultivate eccentricities of behaviour and dress — breaking uniform regulations in an army that had been pretty stiff — removing the wire from his stiff-crowned cap, cap at an angle, riding crop, cigarette holder, turtleneck sweater, corncob pipe. Shrewd leadership, but also individualism — to heck with City Hall. He got away with it.

Two months before the end of the war, MacArthur’s brigade was spearheading the attack in his corps sector toward Metz — only 20 kilometres away. The opposition had been so light that he decided to accompany a patrol forward to see the situation. He got all the way to the outskirts of the city — the Hindenburg Line was practically defenceless, or at least asleep. To him this was a golden opportunity and he recommended that his brigade attack immediately — promising that he could be in the city hall by nightfall. His recommendation got all the way to the Army Group before being disapproved. Plans had already been made for the Meuse-Argonne drive. From his Reminiscences:

“I have always thought this was one of the great mistakes of the war. Had we seized this unexpected opportunity we would have saved thousands of American lives lost in the dim recesses of the Argonne Forest. It was an example of the inflexibility in the pursuit of previously conceived ideas that is, unfortunately, too frequent in modern warfare. Final decisions are made not at the front by those who are there, but many miles away by those who can but guess at the possibilities and potentialities.”

Boldness in offence, frustration over inflexible minds, self-confidence in his rightness — the MacArthur of Korea begins to come through.

MacArthur was the only one of his contemporaries not reduced in rank after the war — Marshall and Stillwell both reverted to the rank of Captain. In 1919, at 39, he became Superintendent of the Military Academy. He fought two battles there: to increase the size of the Cadet Corps against post-war budget slashes and to rejuvenate the instructor staff and curriculum that had become somewhat dead weight and irrelevant.

In 1922, he was off to the Philippines to command a Scout Brigade, and, as an additional duty, to draw up a plan for the defence of Bataan Peninsula. This was MacArthur’s second visit to the Philippines. Prophetically, in his first assignment after West Point, as a 2nd Lieutenant of Engineers, he had worked on, among other tasks, fortifications on Corregidor and a survey of Bataan. In 1925, he was reassigned to the States and promoted to Major General. In 1930, at the age of 50, he took over as Army Chief of Staff.

I have selected two events from his five-year stint as Chief:

In 1931, in the middle of the Depression, a mass of disillusioned veterans marched on Washington — seeking a bonus for their war service. Their claim was fertile territory for incitement by Communist cadres — “We went off to war while others stayed home and got rich. Now we want a bonus to pay the difference for the time we were away." The mob grew to 17,000 and spread all over the parks of downtown Washington. Tension rose. To make a long story short, MacArthur was called upon to disperse the mob as it threatened to march on the White House. He called up 600 troops, led them personally, and the job was done without firing a shot or losing a life. In the aftermath, he was bitterly attacked. He became Public Enemy No. 1 of the Communists. In later years, when the FBI became a bit wiser, MacArthur got his personal vindication, as Communist after Communist defected and told the story of how they had planned to use the bonus marchers to launch their mass struggle. Their big hope was that the troops would fire into the veterans. More important than his personal vindication were the attitudes MacArthur formed about the dangers of Communism. If he was their Public Enemy No. 1, Communism, in his mind, became the threat to his country for which there could be no compromise.

Preserving the Army in the Depression years was his constant battle. In 1933, Franklin Roosevelt succeeded Hoover as President. With the advent of the new Administration, two new measures surfaced. Firstly, Congress proposed a drastic cut in the officer corps of the Regular Army MacArthur fought this tooth and nail and the bill was ultimately tabled. Then came the second onslaught in the form of an Executive Order from the President’s Bureau of the Budget. The Regular Army appropriation was to be cut by 51 per cent. MacArthur, along with the Secretary of War, requested a conference with the President. From his Reminiscences:

“I felt it my duty to take up the cudgels. The country’s safety was at stake and I said so bluntly. The President turned the full vials of his sarcasm upon me. The tension began to boil over. In my emotional exhaustion, I spoke recklessly and said something to the general effect that when we lost the next war, and an American boy, lying in the mud with an enemy bayonet through his belly and an enemy foot on his dying throat, spat out his last curse I wanted that name not to be MacArthur but Roosevelt. The President grew livid. ‘You must not talk that way to the President’, he roared. I said that I was sorry and apologized. I told him he had my resignation as Chief of Staff. As I reached the door his voice came with that cool detachment which so reflected his extraordinary self control: ‘Don’t be foolish, Douglas; you and the budget must get together on this’.”

As they left the White House, the Secretary of War told him: “You’ve saved the Army”, and with that MacArthur vomited on the White House steps.

MacArthur was retired from the Army in 1935 at the young age of 55 and was asked by the Philippine Government to come back as its military adviser. His vanity showed through when he accepted the rank of Field Marshal and proceeded to design his own cap - now famous - with all the braid. Off he went with his Mother and his aide, Major Dwight Eisenhower, and, except for two brief returns to marry a second time and to bury his Mother, he lived in the Far East until his final return in 1951.

During his 36-year career to this point, he had mingled with the highest in the land. He had bucked generals, politicians, Presidents. High political office posed no intimidation for him. On the contrary, if we can pinpoint two characteristics in his make-up at this stage, I feel that the first must be his super-confidence and optimism in his own judgement in company with his seniors, and the second, his deep mistrust of those in power, who, through inflexibility or lack of knowledge of an immediate situation, would impose decisions he felt to be misguided. Nowhere do these characteristics become more evident than in the fall of the Philippines.

On July 26, 1941, with war clouds looming in the Pacific, MacArthur was called out of retirement and designated Commander, US Army Forces Far East, Headquarters Manila. Up to MacArthur’s appointment, the existing plan for the defence of the Philippines called for a retreat to Bataan and denial of the use of Manila harbour. This local plan, called Orange, proved to be in accord with a joint worldwide strategic plan, called Rainbow-5, which called for a defensive strategy in the Pacific and Far East and recognition of Germany as the main enemy. MacArthur would have none of Rainbow. To him, this was defeatism at its worst and sold the Philippines (indeed, one’s own child) down the river. He put the local plan Orange into mothballs and ordered his staff to come up with a plan proposing active defence of all the islands in the Philippines. The new plan stated that there was to be “no withdrawal from beach positions”. The beaches were to be held “at all costs”. This optimism permeated military staffs in Washington. After all, MacArthur was an old soldier of recognized brilliance who, if anybody did, knew his Philippines. He was given a free hand. In fairness to MacArthur, however, the British and Dutch throughout the Far East shared this same optimism. On the morning of 7 December 1941, at Pearl Harbor, the bubble burst.

An aerial view of Manila, capital of the Phillipine Islands

where

General MacArthur was stationed for considerable periods

during his lengthy career.

Because of the international date line, it was 8 December in the Philippines. By noon, about nine hours after the attack on Pearl Harbour, over half of MacArthur’s air force had been destroyed mostly on the ground and the fate of the Philippines foredoomed. Eighteen of 35 B-17s; 53 of 72 fighters were lost against only seven Japanese fighters. The cause of the calamity is one of the shades of gray in the controversy over MacArthur. MacArthur points out correctly that the tactical handling of the Air Force was in the Air Force’s hands — MacArthur was the Army Chief— but as the senior commander, and realizing that the Air Force, especially the bombers, was his most vital weapon at that stage to repel beach landings, one would think that his hand would have been firmly in the Air Force’s back pocket during those first few hours. His Reminiscences are pretty silent about his activities during those early hours. One must assume he was watching the beaches.

On the 10th, the Japanese landed at Aparri and Vigan in northern Luzon, and, on the 12th, they came ashore at Legaspi. MacArthur properly assessed that these were not main landings, refused to shift his forces and waited. On that day (the 12th) he also got his first indication that Washington was implementing Rainbow — Germany first, the Philippines were expendable. A convoy of seven vessels escorted by the cruiser Pensacola had been on its way to Manila — bringing reinforcements of an artillery brigade, 18 new P-40 fighters, 52 A-24 dive bombers, and considerable ammunition. The convoy was diverted to Australia. MacArthur screamed. He screamed also about carriers loaded with planes that had missed destruction at Pearl Harbor, that could and should be sent to him. But war nerves in Washington were too shattered. From his Reminiscences: “It was my impression that our navy depreciated its own strength and might well have cut through to relieve our hard-pressed forces . . . A serious naval effort might well have saved the Philippines and stopped the Japanese drive to the South and East. One will never know.”

The main Japanese landings took place at Lingayen Gulf, 120 miles North of Manila, on 22 December, with a secondary effort at Lamon Bay, two days later. Clearly there was no question about MacArthur’s determination to resist at the beaches, but performance fell far short of plans. Two Philippine divisions met the landings and were scattered. By the end of the day, the Japanese had achieved all their objectives and were ready to break out onto the central Luzon plain. On the 23rd, there was a short-lived success, but soon MacArthur’s forces were in complete retreat. The performance of the untrained and poorly equipped Philippine troops was the clearest sign of disaster. The MacArthur plan for holding at the beaches was scrapped and the old Orange plan for the defence of Bataan was dusted off.

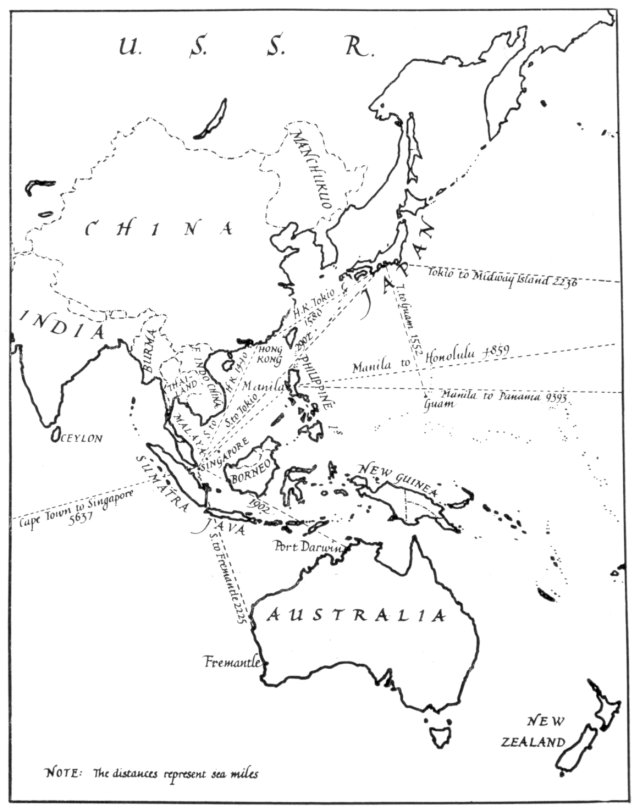

Map showing area in which General Douglas MacArthur

operated during World War II

The rest of the story of the fall of the Philippines is well-known. The withdrawal to Bataan was brilliant — requiring accurate timing and closest co-ordination to pull forces from south and north over single-lane roads and bridges to the peninsula. One slip, one avenue of approach unblocked, one bridge blown too soon or not soon enough - would have brought disaster. The siege of Bataan lasted until 9 April 1942, four months almost to the day after the first Japanese attacks. Corregidor held out another month. MacArthur was evacuated to Australia by order of the President, vowing “I shall return” and received the Medal of Honor. He had emerged from one of our most stunning defeats as a hero — but then, let us face it, we were looking for heroes in those early days. He had become the symbol of future hope in the Pacific. The heroes, left behind in the Philippines, went on the Death March and into Japanese prison camps from which less than half returned.

The extravagant praise given MacArthur in the Philippines does not hold up under scrutiny. I have mentioned the disaster to his air arm. But even before that, one must assess his preparations — he knew war was coming. Despite the fact that defence money was scarce and materials for war in short supply, he could still have done more to prepare the Philippines in the six years he had before 8 December. His troops were painfully unready and MacArthur did not fully realize how unprepared they were. This is what military advisers are for. He had moulded a paper army.

His faith and confidence in his paper army caused him to hold to his plan to defend at the beaches despite the loss of his air arm and the realization that the Navy was scuttling him. The time between 8 December and the main Japanese landings on 22 December should have been used to move supplies into Bataan. Instead, he let them remain stocked well forward for his beach defence, and on 24 December, when he decided to resurrect the old Orange plan, it was too late. Orange called for supply build-up on Bataan for 43,000 men for six months. He was able to move only a third of that and his problems were compounded by the fact that there were not 43,000 men, but 80,000 on Bataan, plus 25,000 refugees. Bataan was starved-out, not outfought. From the troops, who christened themselves the "Battling Bastards of Bataan", came a ballad that was as famous in its day as MacArthur’s “Old Soldiers Never Die” ballad was in his:

The Pacific Theatre, much to MacArthur’s frustration and in violation of the principle of unity of command, was divided into two major commands - MacArthur’s South West Pacific Area and Admiral Chester Nimitz’s Central Pacific Area — one Army, one Navy. Each command had, as its final objective, Japan — and, of course, there was competition and, in fact, bitter rivalry and jealousy, over who would get there first. By late 1943, each command had progressed to the point where strategic planners were being asked “What next?” For Nimitz, backed by the Air Force and the Joint Chiefs, the obvious answer was Formosa. For MacArthur it was, of course, the Philippines. One thing was certain: forces were not available to do both at the same time. Formosa, as can be seen, had many advantages. It was closer to the ultimate objective, Japan, and B-29s could carry heavier loads from Formosa than from Luzon. The Chinese on the mainland were collapsing rapidly — Formosa would provide a better staging area for reinforcements. It was felt that Formosa would have to be seized regardless of the Philippines and its seizure, cutting the supply routes from Japan, would ease the liberation of the Philippines — indeed, perhaps make it unnecessary.

MacArthur contended, as he did in the days of Bataan, that the Philippines, in allied hands, were the key to blocking strategic resources from reaching Japan from the South. To invade Formosa would dangerously expose supply routes to interdiction from air and sea forces based in Luzon and Okinawa. Furthermore, Formosa was a strong Japanese bastion with an unfriendly population the Philippines on the other hand would welcome the allies with open arms, and resistance groups in the hills were still active and, given encouragement, would chop Japanese rear areas to pieces. And most persuasive of all, to MacArthur more was at stake than victory. There was a national obligation not to break faith with his abandoned and imprisoned troops still in the Philippines or with the Filipinos themselves.

In July 1944, a conference was called at Pearl Harbor, with the President in the chair. The Formosa-firsters had a glittering array supported by the Joint Chiefs and Admiral King, the President’s personal military adviser. The conference adjourned without decision, but MacArthur had held his own. For the next couple of months, the battle raged among the various staffs in Washington. In September, the decision was given to go for the Philippines it was to be an Army show.

What went on during those couple of months in Washington is another one of the gray areas in the MacArthur controversy. There are indications that MacArthur may have tapped all his political resources during those two months so that Roosevelt was faced, not only with a purely military decision, but also with the weight of domestic politics. There was no public debate on an obviously top secret discussion but, behind the scenes the powers aligned with MacArthur and his promise “I shall return”, which was blazoned on every American’s heart, were too strong for the President to ignore. Politics was MacArthur’s ally in getting what he thought was right. In the process, however, he was making enemies. When the same type of situation came up seven years later in Korea, it was natural for him, as he said to Congress, to do his duty as God gave him the light to see that duty.

In the aftermath, Formosa was by-passed and the Navy’s Central Pacific Command went on to take Iwo Jima and Okinawa with casualty figures in the two islands alone that, as MacArthur said, “exceeded the entire American losses in the South West Pacific from Melbourne to Tokyo”. In the end it was MacArthur who took the Japanese surrender on a Navy battleship in Tokyo Bay and it was MacArthur who became Supreme Commander Allied Forces and was to supervise the occupation, dismantling and reconstruction of Japan. Again he could turn to his Dad and ask: “How about it, Governor?“

I will skip the occupation of Japan with mention of one short episode, even though MacArthur’s short record as a statesman may go down among historians as greater than his long record as a soldier. I think that it is significant in the light of the overall picture I am trying to present, to recall briefly his dealings with the Russians.

A general view of supplies being unloaded

shortly after the initial landings on Luzon, 9 January, 1945.

The difficulties with which U.S. soldiers

had to contend during "island hopping" are well illustrated

In theory, MacArthur, as Supreme Allied Command was responsible to all thirteen nations — Russia included - who had participated in the war against Japan. In practic it was all-American, and that was exactly how MacArthur intended to keep it. Russia, of course, wanted more of a share in the occupation and, in particular, to have its own area to garrison and control as in Europe. One story goes that the head of the Russian delegation threatened MacArthur that Russian troops would move into Hokkaido whether MacArthur approved or not — because this was their right. MacArthur replied that, if this happened, he would throw the entire Russian mission in jail — to which the Russian replied: “By God, I believe you would.”

In December 1945, three months after the occupation began, no doubt in frustration over MacArthur, Secretary of State, Byrnes, agreed to meet with the British and Russians in Moscow. MacArthur was not invited. The result was the creation of two bodies that were supposed to oversee the occupation. One, the Far Eastern Commission, meeting in New York City, had representatives from all thirteen nations. It was largely ineffective for the four major powers all retained veto rights. In MacArthur’s view it was little more than a debating society.

More of a thorn in MacArthur’s side was the Allied Council, sitting in Japan and composed of the four major powers. Its function was to consult with and advise the Supreme Commander on the spot. MacArthur was supposed to call it into consultation on any important matter. Needless to say he never did. He attended only the opening meeting. MacArthur knew full well that the Russians would try to use the council to defame and embarrass the occupation at every opportunity, so the only answer was to strangle it. This was not always easy, especially with the State Department breathing down his neck.

But MacArthur had one thing going for him throughout his almost six years running the occupation — his supreme self-confidence that he was the man for the job. A military power of seven million armed troops, mostly undefeated in battle, had to be disbanded; a structure for representative government built; police repression abolished and political power decentralized. In short, the whole fabric of the land had to be turned over. This would take strong and firm leadership. It would take someone to whom the Japanese could turn with unlimited respect and even adulation. MacArthur, no doubt, felt that he was the only American who could do the job and, in effect, dared City Hall to find someone to replace him. In the meantime he thumbed his nose at the Allied Council.

Before turning to the last phase, I should like to pause for a brief review of those characteristics of MacArthur that, I believe, play most heavily on the final events of his career. Some of them I have already touched upon.

Certainly here was an egotist of the first water — with confidence, magnetism and flair for the melodramatic. His egotism, however, promoted negative traits, like touchiness and sensitivity to criticism. He could never laugh at himself — he had that inflexible belief of the truly dedicated, of one completely absorbed in the task in hand. He had the capacity to inspire devotion in followers, and he surrounded himself with staff officers who flattered his convictions. Many of his staff who had advised him wrongly in the Philippines, were still with him in Korea. He had no hesitation in bucking City Hall and in using political tools when he thought that U.S. goals were being jeopardized - but he was often naïve, alienating the Press and making enemies who would look for ways to scuttle him. Bold on offence, he really did not know that defence might sometimes be the wiser course. Against Communism there could be no compromise. And finally, one feels, as one follows him along, his deepening mistrust of those in power, conspiring against him perhaps, and certainly misguided. What he said at Metz one feels he would also have said in numerous other situations: “Final decisions are made not by those who are there, but by those miles away who can but guess at the possibilities and potentialities.”

The North Koreans crossed the 38th parallel on 25 June 1950. Without a doubt they were given political-military encouragement by the fact that the U.S. had previous declared Korea to be outside the U.S. defence Line in Asia; by their belief that the U.N. was a paper tiger; and by the knowledge of budget cutbacks in U.S. armed forces whereby U.S. units were at half strength and more interested in climbing Mt. Fujiyama and sipping saki with geisha girls than in preparing for another war. By 29 June, the North Koreans were in Seoul.

On 29 June also, MacArthur flew to Korea to see for himself. Upon his return to Japan, he sent a message to Truman saying: “The only assurance for holding the present line and the ability to regain later the lost ground is through introduction of U.S. ground combat forces into the battle area.’’ Truman bought his recommendation, and on 30 June, authorized full use of U.S. forces available in the Far East. On 7 July, he was able to get the U.N. to declare a similar resolution, and MacArthur became the first U.N. Commander in history.

On 5 July, the first U.S. combat force, a Battalion task force, tried to put a finger in the dike at Osan. MacArthur with his usual optimism, said that the North Koreans would “turn around and go back when they found out who was fighting.” They did not — the task force suffered 150 casualties, lost all its equipment and scattered. The rest of the Division, the 24th, which tried to hold at Taejon, was also scattered, and its Commanding General, General Dean, was taken prisoner. By mid-August, the U.N. Command was holding on for dear life around the Pusan perimeter.

Now comes one of MacArthur’s finest hours — indeed, in my humble view, one of the finest tactical-strategic hours in the history of warfare. As the North Koreans came south, extending their supply lines, MacArthur began thinking, as early as July, of a grand sweep in the enemy’s rear — shades of island-hopping in the Southwest Pacific. As units arrived from the States, though sorely needed to bolster the Pusan perimeter, he held them in floating reserve. On 23 July, a conference was held in Tokyo, and MacArthur outlined his plan — two divisions, almost his entire reserve, in an amphibious landing at Inchon. No one bought the plan. The Navy quite properly warned of the 30ft unpredictable tides in the harbour — within two hours landing craft could be wallowing in mud. Besides, it was typhoon season. The Marines objected to a landing in the middle of a built-up area — right on top of a major fortification, the island of Wolmi-Do. The Air Force reminded him of fog conditions prevailing along the coast at that time of the year. The Joint Chiefs reminded him that his plan would commit his last reserves — reinforcements coming from the States were several months away and there was no assurance that he would get them anyway. The conference adjourned without a decision. On 29 August, largely as a result of his needling and optimism, the Joint Chiefs approved the plan. MacArthur hit Inchon on 15 September, the North Koreans on the perimeter broke on 23 September and, by the end of September, as an organized army they had ceased to exist. Barely 30,000 straggled across the parallel. By 24 October, the U.N. Command was poised along the Chongchon River, the Changjin Reservoir and in Iwon. MacArthur could again ask his Dad: “How about that one, Governor?”

Let us pause to catch up on the politics. Truman, from the beginning, called Korea a “Police Action”, an unfortunate euphemism, but an honest reach for perspective. He was determined to halt aggression, as he had done in Greece in 1947, but he was determined also to limit participation. For him, and with NATO prodding, Korea was a sinister plot to draw off deterrent strength into a non-strategic nothingness. Then, at the right time, all hell would break loose in Europe. For MacArthur, from his Reminiscences: "Now it was clear as it would ever be that this was a battle against imperialistic Communism” (shades of the Bonus March). On 7 July 1950, right after the Osan task force had been clobbered, he put in his first call to Washington for reinforcements. The answer: (1) No increase in U.S. ground forces authorized; (2) a suitable military posture has to be maintained elsewhere; and (3) there was a shortage of shipping. To him this was the same old faulty principle of priorities — Europe first — reaffirming the same indecisiveness that had sacrificed the Philippines.

In late July, MacArthur visited Formosa to co-ordinate defence. Chiang had previously offered two divisions for Korea, but his offer was disapproved by Washington. This visit caused great concern in Washington and, on 6 August, Averell Harriman, the President’s trouble-shooter, was dispatched to Tokyo to explain Washington’s cautious policy toward Chiang. For MacArthur, Harriman's visit was disturbing. Foreign influences were obviously powerful. Policies were defensive and further, “Truman had a violent animosity toward Chiang.” Harriman reported back to Truman that MacArthur had a strange idea that “we should back anybody who will fight Communism”. On 17 August, MacArthur sent a message to the Veterans of Foreign Wars which concluded with these words: “The decision of 27 June lighted a flame of hope throughout Asia that was burning dimly toward extinction. It marked for the Far East the focal and turning point in this area’s struggle for freedom. It swept aside, in one great monumental stroke, all of the hyprocrisy and sophistry which has confused and deluded so many people distant from the actual scene.” In other words, go get ‘em (shades of Metz 1918). Truman ordered MacArthur to withdraw the speech, but it was too late. As Truman said: “I should have fired him then.”

Meanwhile back on the battlefield, on 25 October, MacArthur gave the order to attack: reach the Yalu and bring the boys home by Xmas. What followed was, as we all know, a disaster — one of the biggest failures in combat and strategic intelligence in military history. MacArthur knew there were Chinese facing him, and his intelligence estimated 60,000 “volunteers”. What his intelligence didn’t tell him was that there were seven Chinese armies, 400,000 troops (not 60,000) waiting for him. When he was hit, he naturally called for everything in the book. He ordered 90 B-29s to destroy the Yalu River bridges. His order was countermanded from Washington — he was told he could bomb only the Korean side of the bridges, which his Air Force told him was impossible. He called for a blockade of the Chinese coast, destruction of Chinese industry, and unleashing of the Chinese Nationalists against the mainland. He was told by Washington to prepare to evacuate to Japan; no more help would be forthcoming. While his troops retreated, he pulled every political trick in his hat, and finally he pulled one political trick too many. On 11 April, he was sacked.

When you get right down to it, it all boiled down to this:

MACARTHUR: “The American tradition has always

been that once our troops are committed to battle, the

full power and means of the nation would be mobilized

and dedicated to fight for victory.”

TRUMAN: “I was left with just one simple conclusion. General MacArthur was ready to risk general war. I was not."

MacArthur’s career is a full laboratory of experience and decision-making which touches upon most of the important issues which will ever concern an army or its commander. One cannot help but wonder, just as an aside, that if we had spent more time in the laboratory, perhaps some of our so-called “troubles” in Vietnam might not have become troubles in the first place. One will never know.

On 12 May 1962, at the age of 82, MacArthur returned to West Point to receive his last medal. That evening he spoke before the Corps, a speech lasting 33 minutes, without a piece of paper or speech-note before him. To me this is one of the finest works of oratory in modern history. He had less than two years to live. I’d like to bring you the last three minutes of that speech:

“The shadows are lengthening for me. The twilight is here. My days of old have vanished tone and tint; they have gone glimmering through the dreams of things that were. Their memory is one of wondrous beauty, watered by tears, and coaxed and caressed by the smiles of yesterday. I listen vainly, but with thirsty ear, for the witching melody of faint bugles blowing reveille, of far drums beating the long roll. In my dreams I hear again the crash of guns, the rattle of musketry, the strange mournful mutter of the battlefield. But in the evening of my memory, always I come back to West Point. Always there echoes and re-echoes in my ears — Duty, Honor, Country.

“Today marks my final roll call with you. But I want you to know that when I cross the river my last conscious thoughts wih be of the Corps and the Corps — and the Corps.

“I bid you farewell.”

THE AUTHOR

Colonel F. E. Wagoner was born at Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S.A. on 10 March, 1927. He graduated in 1948 as a Bachelor of Science from the U.S. Military College where he took up a commission as 2nd Lt in the Field Artillery.

During the next three years he served his regiment in various capacities,finally being posted to the Army of Occupation in Germany. In 1952, he became Battery Commander, 27th Arm’d Field Artillery Battalion at Fort Hood, Texas. After attending the Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, from 1953 to 1954 he was posted to the U.S. Military Academy, West Point as Staff Officer, 1802nd Regiment. From 1956 to 1958 he held the offices of Artillery Adviser Matsu Defence Command and Armoured Force Command, Taiwan. He served as Instructor and Project Officer at the Artillery School, Fort Sill from 1958 until 1961 when he entered the Command and General Staff College, at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, as a student. During the years 1962 and 1963, he was engaged in pursuing a course in African Studies at the American University, Washington, D.C. and at the University College, Salisbury, Rhodesia. In 1964 he was posted to the American Embassy, Bujumbura, Burundi as Army Attaché, and from 1964 to 1966 he held the same appointment in Kigali, Rwanda, relinquishing it on being made Battalion Commander, 3rd Bn, 38th Artillery (Sergeant Missile).

Colonel F.E. Wagoner

For his distinguished services he was awarded the Legion of Merit; the Joint Services Commendation Medal; the Army Commendation Medal and the Army General Staff Award. However, with all his responsibilities, he had not neglected his studies and in 1968 his thesis on International Relations and Organisation earned him a Ph.D. From 1968 to 1970 he served as Director of International and Civil Affairs on the Staff of the Army Chief of Staff, Washington D.C.

In December 1970, Colonel Wagoner was posted to South Africa as Army Attaché at the American Embassy in Pretoria.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org