The South African

The South African

"I learnt more in one day with the Natal Carbineers than I had learnt

in 10 years with the regular cavalry."

So said Major (as he then was) Gough of the Lancers. Many South Africans

must have served under him when, as Lieut.-General Sir Hubert Gough, he

commanded the Fifth Army on the Western Front during World War I. Few of

them can have realised how much he owed (as he generously admitted) to

the South African troops with whom he served during the Natal campaign

of 1899-1900.

One such person, however, was the late Colonel Park Gray, a Natal Carbineer from Loskop in the Natal Midlands. A fine horseman and a crack marksman, he joined the Carbineers as a teenage trooper in 1898. Very soon he got his stripes and eventually commanded a regiment.

He could tell at first hand much about the celebrities of Buller's Army. He was in particularly close touch with Major Gough (as he then was) on Lord Dundonald's staff. Dundonald, inevitably known as Dundoodle, was the much publicised and overpraised officer commanding the mounted troops in the Ladysmith Relief Column. Though not rated very highly by the troops under his command, it was to his credit that he allowed himself to be influenced by Gough who, in turn, was a willing disciple of Major Duncan McKenzie. The latter commanded No.5, the only squadron of the Natal Carbineers which had not been shut up in Ladysmith. Duncan McKenzie, a household name in Natal, was destined to achieve high honours and become General Sir Duncan McKenzie. As a mounted infantry officer, he was supreme. Due to his teaching, Gough became the kingpin of the cavalry of Buller's forces. As a regular officer, Gough had the ear of the regular "top brass" and, learning the know-how of the "Colonials", he was able tactfully to pass it on to Dundonald.

Men of No.5 (Estcourt and Weenen) Squadron of the Natal Carbineers were farmers born and bred and trained in the Natal Midlands exactly where they were most needed. They were brigaded with the only squadron of the I.L.H. which had also escaped being shut up in Ladysmith.

British Cavalry were unsuitably equipped, as Park Gray immediately observed, and their training in reconnaissance work was so lacking as to be positively dangerous. The British troopers were well liked, but even the kindly charitable Park Gray could not conceal the fact that he shared the widely held opinion that their officers were supercilious and rude. He found certain remarks, made by the Officer Commanding the 5th Lancers, after their charge at Elandslaagte, thoroughly distasteful. These remarks were bitterly resented by the Boers. He was, however, firmly of the opinion that, for disciplinary reasons, a quota of regular cavalry officers much improved the regiment's quality.

Captain Gough, unattached and looking for a job, arrived in Durban on 23 November 1899. He was immediately sent up to Nottingham Road by the night train and within a few hours went out on a patrol of which Park Gray was a member. To use Gough's own words: "Here I joined a Rifle Association (actually a squadron of the Natal Carbineers) composed of about 80 loyal Natal farmers, riding their own horses and providing a few necessaries in the way of kit. I found them a friendly, practical body, ready to fight when required, but not at all inclined to gallop thoughtlessly into danger. My military experience of this war began at once. At dawn next morning we set forth on reconnaissance east of the railway. Riding with these Natal farmers, I covered about 30 miles and back in a day and returned to Nottingham Road the same evening. We did not encounter any Boers, but in that long ride I had been taught more about reconnaissance than I had learnt in over 10 years' service in the cavalry. They moved by bounds, like wild animals carefully approaching their prey, and this has now become the classic method of advance for scouts."

Next day - 25 November - there was another reconnaissance. Gough had his second lesson, in which he was shown how to cross a swiftly flowing river (the Mooi) and how to slaughter, skin and cook a sheep; essential arts omitted from the orthodox cavalry training curriculum. This time a large body of Boers was sighted and shadowed. Valuable information of their movements was gleaned and transmitted to Headquarters. Gough concludes: "This reconnaissance, the credit for which belonged to me in a very small degree, started my reputation in Natal as a good reconnaissance officer." He was forthwith appointed to Lord Dundonald's staff; but he was aware of his limitations in this kind of warfare and was ready to learn, always giving credit to the teachers. The Carbineers much approved of his appointment.

The Carbineers liked the Tommies very much but grieved to see how ill-equipped and trained they were for war in South Africa, how little initiative they had and how completely lost they were without their officers. Infantry and gunner officers were liked and respected for their devotion to duty and bravery. It was saddening to see how badly they were attuned to this new type of warfare. They had no feelings of hostility towards the Boers or of superiority over the "Colonials". Park Gray often acted as galloper to McKenzie and so had ample opportunity of observing Buller and other senior officers.

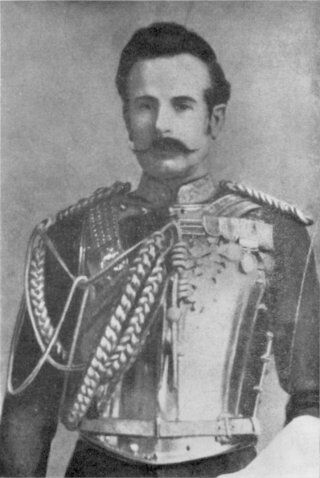

Colonel Park Gray

Park Gray met Churchill several times. The first occasion was when he heard that a certain odd type of war correspondent was offering £200 to anyone who would smuggle him into besieged Ladysmith. To Park Gray this seemed easy, so he immediately went to a canvas bivvy in the goods yard of Estcourt railway station to offer his services. Here he found Churchill, who, he said, "looked very depressed and was very pink and white in the face and looked no more than 18 or 19. He looked like a blushing bride." This description is very like the one given of him by his Boer captors a few days later. Park Gray felt himself being weighed up very shrewdly -- he, too, was only 19 - but eventually Churchill decided to trust him and accept his proposals. There would be no difficulty in getting through the Boer lines. They would go via the Drakensberg as others and many natives were doing. There were two possible snags - one was to get three days leave and the other would be to get safely through British pickets. Mounted men were very busy at that time and were more in the saddle than out of it. McKenzie, therefore, not surprisingly, demurred when applied to for three days leave. "Why did Park Gray want leave?" "To take someone into Ladysmith." "Who?" "A war correspondent." Then, said Park Gray, the storm broke. "Three days for a particularised war correspondent!" This was the text of a refusal, expressed in terms so picturesque that Park Gray stored it up with other treasured and useful memories.

Unfortunately in telling Churchill of his disappointment, Park Gray quoted McKenzie rather fully, especially those passages which referred to war correspondents. Churchill "seemed quite moved" - no doubt something of an under-statement. In any event he was definitely not amused and, ever after, the Colonial troops felt he had a down on them. This feeling was actually unjustified. Churchill's despatches were always slanted to suit his readers in England, and were quite often inaccurate, but he was never unfair or prejudiced. He was more than generous towards the Boers and there is no real evidence of his belittling the Colonials. His account of the armoured train engagement is a model of lucidity. He gives high praise to Captain Wylie of the Durban Light Infantry and to the engine driver. He refers to his own exploits with becoming modesty.

After his escape from captivity in Pretoria, Churchill rejoined Buller's Army. Most surprisingly but, probably because of the favourable publicity his exploits had received and quite against accepted policy, Buller agreed to his being commissioned (unpaid) in the South African Light Horse and, at the same time, to his remaining accredited as a war correspondent. Thus protected by his uniform and, one suspects, because of his fame and aristocratic relations, he went more or less where he liked, rather to the chagrin of other correspondents who remained mere civilians. In any event he was now in a fine position to go where the best chance of a good story offered. These stories were always good but not always accurate. His description of a crossing of the Tugela by the mounted troops is hopelessly inaccurate, and it is hardly surprising that the Carbineers were offended.

This is how he describes it: "About a quarter of a mile down stream from Trichardt's Drift there is a deep and rather dangerous ford. Across this at noon, the mounted men began to make their way and, what with the uneven bottom and the strong current, there were a good many duckings. The Royal Dragoons, mounted on their great horses, indeed passed without much difficulty, but the ponies of the Light Horse and Mounted Infantry were often swept off their feet, and the ridiculous spectacle of officers and men floundering in the torrent or rising indignantly from the shallows provided a large crowd of spectators with a comedy. Tragedy was not, however, altogether excluded, for a trooper of the 13th Hussars was drowned and Captain Tremayne of the same regiment, who made a gallant attempt to rescue him, was taken from the water insensible."

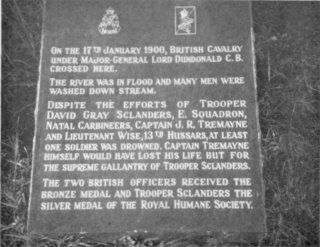

Now this account is a travesty of what actually happened. McKenzie and Park Gray were, of course, both present and their accounts agreed in all details. The Carbineers crossed first. The river was full but the crossing presented no serious difficulties. The cavalry then approached with some trepidation and little confidence; it looked so dangerous. The Carbineers remained to show them where and how to cross: "Horses' heads upstream; don't look at the water; keep your eyes on the opposite bank." But the troopers were soon in difficulties and the Carbineers were ordered back to the river in a hurry. Trooper Sclanders had already pulled out an unconscious Lieutenant Tremayne who had himself been swept away in a vain attempt to rescue one of the Hussars. Sclanders then rescued another Hussar, and the Carbineers, forming a human life line, rescued several more. Sclanders was awarded the Royal Humane Society's silver medal and Tremayne their bronze. A granite tablet has been suitably inscribed and will be erected at the edge of the new Spioenkop dam under which Trichardt's Drift will lie at a depth of several hundred metres.

Plaque indicating the crossing of the Tugela River on 17 January 1900.

The drift is now under the Spioenkop dam.

Soon after the crossing a strong party of Boers, for once unaccountably off their guard, was ambushed by the Carbineers at Acton Homes. Accounts vary in detail, but Park Gray's is obviously the most accurate and the credit for the success is entirely McKenzie's.

The Boers having been spotted, two Carbineers, one of them Park Gray, were sent racing ahead to reconnoitre a ridge which the unsuspecting enemy would have to pass. The ridge was found unoccupied and the rest of the troops were then signalled to come up. This they did at the gallop and, making skilful use of cover, they reached the ridge unobserved. The Boers were at their mercy and, but for a premature shot, few, if any, would have got away. Park Gray had himself been under aimed fire with sparse cover a few weeks before at Hlongwane, and he now found the tables turned. He hated the experience and found it hard to fire to kill. In bringing succour after the engagement, he spoke to a wounded man, named Moodie, whom he had hit. He was an English-speaking burger of the Transvaal, with whom all his sympathy lay, and he had married a Boer girl. His thigh had been shattered and he was in great pain, but he eventually made a good recovery.

A story that there had been an abuse of the white flag was condemned by Park Gray as quite untrue. He contended that almost every such alleged abuse on both sides, and there were many, was due to genuine misunderstanding and not to treachery. Churchill gave an account of the action - good journalese and reasonable history. He admits that he arrived very late in the action, as did Dundonald. Park Gray, however, did not think much of Churchill's description of himself as a "young fairhaired gentleman" who described the action in "a delicate voice" as a "vewy (sic) astonishing display of fire."

Dundonald, pleased with the success of his men and prodded by Gough and McKenzie, greatly daring, begged Warren, the Divisional Commander, to detail infantry and artillery to reinforce, in order to widen the now obvious gap in the Boer defences. Dundonald argued and stood up manfully to Warren who treated him abominably, and a golden opportunity was lost.

Colonel the Earl of Dundonald, C.B., C.V.O.

In the end all that Dundonald achieved was to have all the regular Cavalry taken from his command and he was left with the despised Colonials. Thereafter Warren practically ignored Dundonald and left him to his own devices. The snub was almost unbelievable, but the Carbineers and I.L.H. continued cheerfully with the good work. It even suited them, for they could always be where they were needed and they suffered none of the "regrettable incidents" which the regular Cavalry suffered all too often.

The first of the relieving force into Ladysmith were the Carbineers and I.L.H. in parallel files with McKenzie and Bottomley leading their respective regiments. Gough who was senior officer ignored Dundonald's timid order to hold back. He was probably present, as he claimed, but must have held back in the rear to allow the Colonials the honour. Park Gray did not see Gough that day but thinks that is what happened. Churchill's account of the entry is very exciting and dramatic. Though he does not actually say so, one might infer that he was actually present and that he galloped across the plain to be practically the first person to greet Sir George White, the defender of the town. This was certainly not the case, and Gough and McKenzie were at dinner with Sir George quite a time later, when Churchill and Dundonald burst dramatically in upon them.

Brig.-Gen. Sir Duncan McKenzie, KCMG, CB, DSO, VD.

The composite regiment of Carbineers and I.L.H. was ordered to be ready to mount at dawn the next day to pursue the retreating and demoralised Boers. It was with unbelief and anger that they found that Buller had countermanded the order which, if carried out, might well have resulted in a Boer disaster of the magnitude of Paardeberg.

Earlier Churchill had dropped something of a brick which amused Park Gray immensely. He wrote of the fatuity of the sermons of the C of E chaplains and compared them unfavourably with those of certain R. C. priests in the field. These remarks so infuriated Lord Roberts that it was only with great difficulty that he was persuaded to permit Churchill to continue as a war correspondent. Randolph Churchill, Winston's father, had been very friendly with Roberts and had helped him greatly in his Indian Army appointments. In spite of this Roberts, goaded, it is guessed, by Lady Roberts, actually cut Winston dead when they met in Bloemfontein.

The last semi-official military act of Park Gray took place a few months before his death. It fell to him to represent the Carbineers at the exhumation of the bodies of three Carbineers and two I.L. Horsemen who had been killed at Hlongwane on 15 December 1899. These men had been buried on the day after the battle, Hamilton Baynes, Bishop of Natal, officiating. Park Gray had been present. One of the Carbineers was David Gray, a cousin; he too had been a crack marksman. He had been shot through the heart while rashly exposing himself to get a better aim. He died in Park Gray's arms. Park Gray knew exactly what type of wound each of the dead men had received, and he was visibly moved when the remains were revealed. He had, not surprisingly, disliked the idea of exhumations but came to recognise that, in this case, there were special reasons. He approved, as did the Regiment, of the new site at Clouston Koppie of Remembrance where a tall copper cross has been erected. The new graves were consecrated by Bishop Inman of Natal in 1964. A granite tablet, suitably inscribed, marks the site of the original graves near Chieveley.

As an old man, Park Gray retained all his faculties. His memory was unclouded and his descriptions of events, of which he had first-hand knowledge, were meticulously accurate. His criticisms and his appraisals of character were reasoned and just and never malicious or barbed.

Had he written an autobiography, it would have been notable for its moderation and modesty. Invaluable historical material has been lost because the autobiography was never written, although some interesting facts have been salvaged from a few private letters and recorded conversations with the author. The authenticity of this material is unquestionable.

NOTES

REFERENCES

1. "London to Ladysmith via Pretoria", Winston Churchill.

2. "Delayed Action", Gordon McKenzie.

3. "Soldiering On", Hubert Gough.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org