The South African

The South African

as told by LT.-COL. C. L. ENGELBRECHT, DSO, ED and CAPTAIN W. J. McKENZIE

Edited by MAJOR D. F. S. FOURIE

The narrative is related by Lt.-Col. C. L. Engelbrecht, and only by Captain W. J. McKenzie when specifically indicated.

While the Brigade was in training at Barberton, I was sent on a refresher course to the South African Military College, Voortrekkerhoogte. I was engaged on a tactical exercise when a courier arrived to take me to Pretoria in a staff car. Without any explanation, after being allowed only a few minutes to take farewell of my family, I was put on the train for Barberton. At Barberton, I was told by Brigadier Senescall that the Brigade had been ordered to Durban by motor transport for exercise purposes. The Brigadier bad to leave Barberton before the Brigade for some reason which he did not disclose. I was to act in his stead and my first task was to draft the movement order.

The movement order was prepared at once but, before it could be distributed, Brigadier Senescall returned briefly to explain that a special task had been allotted to the Brigade. All he would say was that the Brigade was not being sent very far and would not be away long. That was the only information he would or could disclose. His caution that the Brigade "had to be prepared" was to be the prelude to the most secret operation to which I was ever party.

Several days after Brigadier Senescall's visit, Defence Headquarters instructed the Brigade to entrain at Carolina. Twenty-four hours ahead of the departure time, I sent Captain D. B. H. Grobbelaar, a company commander, with an advance party to Durban. Entraining was effected under cover of darkness with trains leaving at times scheduled by Defence Headquarters. Because of the number of trains, different routes were used. Some went via Piet Retief and others by way of Standerton.

The degree of secrecy with which the move was accomplished can be gauged from the fact that when I saw the Divisional Commander, Major-General Manie Botha, at Carolina station just before I left by the last train, he complained bitterly of how Defence Headquarters had taken away his Brigade without even telling him.

Once in Durban the Brigade, without the customary embarkation leave, embarked on several ships waiting in the harbour and it was only then that I discovered that our destination was to be Madagascar. The intense secrecy was due to the belief that the Japanese, if not already in occupation of the island, were on their way. Under no circumstances should they gain any inkling of the projected invasion by a relatively weak joint British-South African force.

The 7th Brigade reached Madagascar and landed peacefully enough at Antsirane in the neighbourhood of Diego Suarez. The Brigade was given the task of defending Diego Suarez in the event of a landing by the Japanese or a counter-attack by Vichy French forces on the island. The role of the Pretoria Regiment was defence against any attack from the west. This was expected to come from Basse Point, a beautiful beach, overgrown with coco-nut palms and situated 20 miles from the harbour and considered to favour a Japanese landing. While encamped at Damanakie, five miles west of the harbour, the men of the Pretoria Regiment were put to work digging trenches on the high ground of Avril quest which overlooked the whole area from which the Japanese were expected, and gave clear fields of fire.

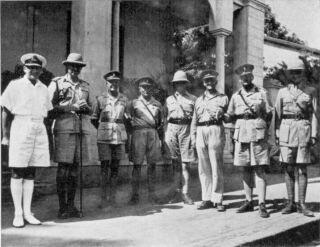

Senior Officers from British and South African forces at the march-past at Diego Suarez shortly after landing in Madagascar. Left to right: Rear Admiral Tennant, Brig. F. Festine, DSO, Brig. G.T. Senescall, DSO, Col. Melville, Lt.-Col. F. Emslie, Lt.-Col. C.L. Engelbrecht, Officer Commanding the Pretoria Regiment, Brig. W.A. Dimoline, Lt-Col. Stockwell.

Between Basse Point and Avril quest, the terrain was ideal for defence. The road was good but, off the road, the ground was, for the most part, quite impassable for vehicles. The rugged surface was broken by small but steep slopes that only infantry could negotiate. Brigadier Senescall told me that, if an attacking force, too strong for the Brigade, should land, the Pretoria Regiment would have to hold them off long enough to allow the rest of the Brigade to make good their escape by sea. Although the Brigadier said that this would mean that the Regiment would embark last, my opinion was that the job could only be done successfully if the Regiment did not embark at all. In order to maintain morale and security, I withheld this information from all my officers except Captain Grobbelaar and Lieutenant Basil Goldsworthy. Even then I hesitated to tell them of my actual intentions.

I told Goldsworthy to make a thorough reconnaissance of all the rugged terrain to our left, as this was ideal for combat.

My intention was that Goldsworthy should harass an enemy advance from Basse Point, thus forcing the attackers to protect their right flank. This should provide time for the withdrawal of the remainder of the force. At the same time, I arranged for the establishment of clandestine ammunition dumps. In the event of our being unable to escape, these would enable the Pretoria Regiment to engage in guerrilla operations against the Japanese rather than meekly to surrender. I decided not to let Brigade Headquarters in on my plans. One can usually count on higher authority to dampen initiative.

In the meantime the Regiment gained some good experience from building strong defensive positions on Avril quest and the hard work alleviated their boredom.

The initial fear of Japanese omnipotence at the beginning of 1942 had eventually abated and we began to prepare for action against the Vichy authorities on the island. On 9th September, "C" Company was detached and given all available transport. Due to a shortage of motorised vehicles the remainder of the battalion had to make do with bush-carts drawn by Malgache oxen - the carts that had earned Mr Oswald Pirow, former Minister of Defence, so much opprobrium when it was found that South Africa had insufficient motor vehicles for her army. The detached Company and its commander, Captain Danie Grobbelaar, passed under the direct operational command of the British 'Island Headquarters' for an operation against the French along the east coast.

Early on the morning of September 24th, I was unexpectedly ordered to report to HMS Birmingham for orders I took my adjutant, Captain W. J. McKenzie, and, proceeding to Antsirani, we boarded the cruiser which lay at anchor in the harbour. We met Brigadier Senescall on board and were taken by him to an order-group where he introduced us to Lt.-Gen. Sir William Platt, KCB, CBE, DSO, General Officer Commanding East Africa, who had flown in from Nairobi. Admiral Tennant was also present. Captain McKenzie remembers that Major-General Sir Bernard Freyberg, VC, the New Zealander, was there as well as a number of other senior officers of the three services.

General Platt explained that the Vichy French forces under Governor Annet were persisting in their resistance and had no intention of surrendering. The rainy season was at hand and soon it would become impossible to operate. Approximately 900 miles south of Diego Suarez was another harbour called Tulear. This had to be captured, with considerable force, if necessary. The object was to secure a foothold in the south, with a view to the complete occupation of the island of Madagascar. The Navy would take the Pretoria Regiment to Tulear to help in establishing a beach-head to enable General Platt to attack the French in the rear, as a preliminary to capturing the capital, Tananarive. There was no reliable information on the strength of the French at Tulear, although it was believed that there was at least a company.

Captain McKenzie remembers that the plan for the landing was then fully discussed and takes up the narrative here. "The Naval officers produced charts showing the safe approaches to Tulear, the extent of the tides and other information useful for effecting an amphibious landing. It was decided that two companies of the Pretoria Regiment together with some additional troops would sail for Tulear on the Empire Pride, escorted by HMS Birmingham and two destroyers. The force would be known as ENCOL, a contraction of Engelbrecht Column, a popular way of designating forces.* At this stage General Platt asked how long it would take Lt.-Col. Engelbrecht to transfer his troops to the ship. Lt.-Col. Engelbrecht indicated that I should reply and I said, 'two hours'. When it was suggested that I was being a little optimistic, I answered, 'You do not know our Colonel and you do not know what our Regiment can do'. This settled the matter and we were told to arrange for immediate embarkation. It was also ordered that Lt.-Col. Engelbrecht and Captain F. P. Kightley (a nephew of the Boer Scout, Danie Theron) should travel on HMS Birmingham so that they could plan the landing at Tulear with Admiral Tennant. " * *

[*The force was to consist of 21 officers and 246 other ranks as well as 11 Non-Europeans from PR, a loading party of 32 and elements of SA 2nd Echelon, Brigade Signal Coy, 88 Field Company SAE, 19 Field Ambulance SAMC and Brigade Workshops. Our transport was three armoured cars, five one-ton trucks and six motor cycles.] [** (Footnote: Colonel F. P. Kightley is now Deputy Chief Scout of the Boy Scouts of South Africa).

At this point General Platt showed me a map of the town of Tulear, showing the position of the wireless station, the banks, post office and other important centres. He explained that our first task would be to secure the wireless station. He expressed the hope that Tulear would be captured without fighting but that, if there were no alternative, force should be used. As far as the local inhabitants and officials were concerned, I was free to use my discretion. He wanted no prisoners of war because he lacked facilities to care for them. Preferably only regular soldiers, likely to cause trouble later, should be imprisoned, unless they showed that they were ready to co-operate.

Before leaving him, I reminded him that the Pretoria Regiment had had no amphibious training. He replied that, during the three days' voyage, the Regiment would be properly trained for the Operation. We then took our leave.

The Regiment's two companies embarked in the afternoon of the 25th and we left harbour early on the morning of September 26th. By this time, I had been equipped with a political officer whose task would be the civil administration of the captured territory. The Admiral lived in his day cabin on the bridge for the voyage and gave me his stateroom which I shared with Captain Percy Kightley, a live wire, with plenty of drive and determination. The Regiment's second-in-command, Major D. J. Louw, and the adjutant sailed on the Empire Pride with the Regiment.

Captain McKenzie recalls: "Even before we left harbour on the 26th, Major Louw had been ordered to have the men trained in the use of landing craft. This training was given by Royal Navy and British Army officers accompanying the Regiment. By the time we reached Tulear, the men had become expert at handling the unfamiliar vessels. One of the British officers casually mentioned to me that the War Office was awaiting with interest the result of the landing, with a view to similar landings later in the war. It was his task to furnish a detailed report on the operation for this purpose. I little realized the significance of his remarks then."

Men of the 7th South African Brigade approaching Diego Suarez

at the end of their ocean crossing from South Africa.

A message to be sent to the highest French official in Tulear, the 'Chef de Region', ordering him not to fire but to withdraw his troops from their positions to the barracks. Should they resist, the Naval vessels would fire on Tulear.

The two Walrus planes to reconnoitre the area of Tulear, especially the roads from the west.

Captain Sheard with 'A' Company to establish the initial beach-head, followed by the Royal Marines, with Captain Dredge and his compauy in reserve on board ship.

The naval guns to be kept in readiness to give support. I would stay on the Birmingham initially to designate the targets to be shelled.

Once the beach-head had been established, the wireless station captured and it had become clear that there would be no resistance, the troops would take control of the banks and other important establishments, as a safety measure in case of riots. Meanwhile Battalion headquarters would be established ashore.

The proclamation of martial law was an essential part of our plan for subduing Tulear and it was the responsibility of our political officer, Captain Mortimer, an Oxford Don in peacetime, to prepare it. He confessed, however, that he had forgotten to obtain General Platt's signature to it before we left. Despite my having no authority at all, I was quite happy to sign the document on behalf of His Majesty King George VI. To my knowledge, the Sovereign suffered no inconvenience from my doing so - and nor did we.

Allied Forces landing at Tamatave.

As we neared Tulear a boat fetched Major Louw and Captain McKenzie from the Empire Pride. On HMS Birmingham, I gave them my orders for the operation. I warned Major Louw against dispersing the troops too widely before I could join them to take personal tactical command ashore, should there be a fight.

Our little fleet entered Tulear harbour at 0630 hours on September 29th. The picture was one of brooding silence. Nothing could be seen moving. Later we discovered how lucky we had been, when a French resident of Tulear told Major Louw that a coast gun had been emplaced on the beach below his house. When he saw the ships, he ran down to the gun, arriving as the Malgache N.C.O. was ordering fire to be opened on the nearest ship. Only with difficulty, did the French civilian succeed in dissuading the N.C.O. from inviting retaliation from the cruiser's guns.

The whole operation ran like clockwork, even though the armoured cars stuck in the mud. As soon as the amphibious landing craft (ALC) touched the beach, it was clear that there would be no resistance. Nevertheless, all the drills were followed in case of deception by the French. The first ALC, carrying one section from 'A' Company, beached 200 yards north of the pier, and the troops ran through about 200 yards of water to establish a beach-head, as the other ALCs followed some 800 yards behind with the remainder of 'A' Company, a platoon of 'B' Company to act as a landing fatigue, and then the Royal Marines.

While 'A' Company consolidated the beach-head, one platoon went to the wireless station which they captured before 0900 hours.

The Marines, under the command of Captain Forrest, went west of the road, leading from the pier to the market, and, while covering the sea front, occupied several government buildings. In the meantime, another platoon, commanded by 'A' Company's commander, advanced in a line between the town and the wireless station to the Malgache barracks.

At the barracks only about 30 Malgache soldiers remained under the command of a French lieutenant. Across the road from the barracks, 'A' Company discovered a camp of Tirailleurs (light infantry). Here there were about 50 Tirailleurs commanded by a commandant (major). No resistance was offered and all the troops were made prisoner in the barracks.

I followed close on the heels of the landing and, immediately after my arrival, a message from the wireless station was intercepted. It said simply, "Anglaises landed in Tulear" (in French, of course). It was the last message before the station was captured, but it was enough to put us on our guard against counter attacks.

Patrols were immediately sent out to gain information as to what the interior concealed. One patrol went along the road Tulear-Maroala for 15 miles, It encountered no opposition, although it found a portable wireless transmitter hidden in a native hut. This was put out of action. Telegraph and telephone wires had already been cut the day ENCOL landed. A second patrol went to St Augustin to search for a detachment of troops along the road, but they had fled. North of the town some Tirailleurs were found by a patrol and taken prisoner. Below the Chef de Region's house, another patrol captured an 80 mm mountain gun (made in 1878) and ammunition, the gun crews fleeing on seeing the South Africans. During daylight, the Walrus aircraft searched the road approaching Tulear.

I ordered Major Louw to make contact immediately with the Chef de Region (a sort of provincial or district administrator), the Maire-administrateur (a sort of mayor-cum-town-manager), the Commandant de Police and other officials, and to place them under guard so that our political officer could not get at them. The reason for this I shall explain later.

Next I visited the barracks. Having seen the prisoners safely guarded, I left them for a while and went to the airfield. This had been rendered unusable by the French who had scattered large tree stumps over the runways. Having given orders for the airfield to be cleared, I returned to battalion headquarters.

At headquarters, Major Louw was waiting to tell me that the Chef de Region and other officials and leading personalities were waiting in the Chef's office. The task I now set myself was to persuade the civil authorities to continue administering the area, for it was beyond our strength and capacity to do so. I had previously discovered that the British political officers, whose task this really was, had bungled the job badly elsewhere. Their method was to ask the officials directly whether they were pro-De Gaulle or pro-Petain and to throw out the latter. It seemed to me that it would naturally be difficult for officials who had been serving Vichy up to that moment and whose country's politics were so confused, to reply immediately that they were pro-De Gaulle. It was natural that hostility would be aroused, and the political officers would fail to secure any co-operation at all.

I sent for the political officer to act now only as my interpreter. It was clear that my hand was strengthened by General Platt's having authorized me to appease the French once Tulear was taken. The political officer was to say only what I told him to say.

I started with a short speech, telling the French officials how I regretted the lowering of their national flag and the hoisting of my country's flag in its place. (This had once happened in my own country and I knew how it saddened people!). I explained that it was the custom for troops to do this after conquering a city, and that we were there not to conquer Madagascar, but only to forestall the Japanese. So saying, I told them that the French Tricolor could again be hoisted alongside the South African flag. (In spite of being part of a British force, we took care to raise only the South African flag, not the Union Jack.) I saw that this had a visible effect on the Frenchmen who had been looking both downcast and hostile.

Next Captain McKenzie read the proclamation, instituting martial law, to the officials, and it was pointed out that the British government guaranteed their salaries. I assured them that I was not interested in whether they were pro-De Gaulle or pro-Petain; I was only interested in carrying on the civil administration in their own interests. My only condition was that, if anyone should act in a manner harmful to my force, he would be severely dealt with by the military authorities. I also waived minor restrictions, such as the possession of cameras, and then let them discuss my terms. After a short discussion, all the officials agreed to co-operate. When the Commandant de Police pointed out that his district police had been disarmed, I ordered Major Louw to return their weapons.

Certain other details were arranged with the Chef de Region, and then the political officer proved his goodwill by distributing unobtainable food and other necessities. Finally the band of HMS Birmingham performed in the town square that night.

On the following morning, I went to the barracks to see the military prisoners-of-war paraded. Most were Malgache colonial troops with French reservists as officers and N.C.O.s. I asked them whether they wished to continue being soldiers. If they did, they would have to go across the blue waters, and I pointed out the ships to them. If they did not, I was agreeable to releasing them on parole. I promised that their wages would be paid up to date. (My promise was carried out with money taken from the barracks safe and which, the French commanding officers told me, was military funds. The unused portion of the money was deposited in a local bank to the account of the British government.) The soldiers were quite amenable to my suggestions, so that I now had the co-operation of the whole town.

Once I had ensured the co-operation of the French, I allowed the banks to re-open, and I withdrew the pickets. One of the managers told me that an official of his bank had gone to Tananarive to fetch a large amount of cash, and he asked that the man be allowed to re-enter Tulear. Captain O. G. Sheard was detailed to arrange his safe return. At the same time, when a friendly Frenchman confided in me that he had buried all his money, I reminded him that my proclamation provided for its confiscation, if it were found. He was thus happy to take my advice and redeposit it at once. The course of action I chose was designed always to placate the French whose feelings were particularly sensitive, regarding the defeats they had suffered. Even when the Mayor, who was most unfriendly towards us, complained that our 'tanks' (i.e. armoured cars) were damaging his streets, I gravely assured him that I would speak to the officer in command of the 'tanks'. Although I never did bother to do so, the Mayor was a little more friendly after that.

We were surprised at the lack of resistance, but accidentally the Chf de Region let on that 10 days before our landing, 200 troops had been despatched inland and more had left for Ihosy on September 27th. It was surprising that they had left, because defensive positions had been laid out on the beach overlooking the bay and, along all the roads to the town, trees had been laid as roadblocks, but there had been no demolition of installations.

The crowning reward for the goodwill that we managed to secure was demonstrated when the Chef de Region, after watching our conduct and after satisfying himself that France's honour was safe, offered Admiral Tennant and me the use of his official car for the execution of our duties.

Planning and executing an amphibious landing had been an exhilarating experience. The operation, according to a cable from Admiral Tennant to General Smuts, was probably the first made up exclusively of South African troops and Royal Navy and Marines. The Admiral reported that, with a little more practice, he believed that the Navy would make us completely web-footed.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org