The South African

The South African

by C.J. Barnard

This article is a transcription of a talk by Professor Barnard of the University of South Africa to the S.A. Military History Society. For a detailed account, fully documented, on General Botha's role in this battle the reader is referred to Professor Barnard's book Generaal Louis Botha op die Natalse Front, 1899-1900 (Cape Town 1970).

Those of you who attended my talk on General Louis Botha's role at the battle of Colenso will recall the main features of his conduct of that fight. At the beginning of December 1899, about two months after the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War, General Botha, who was then, at 37, the youngest general in the Boer forces, was put in command of the Tugela front at Colenso. Here he was to face the British army under General Sir Redvers Buller, which was to attempt to relieve the encircled British troops at Ladysmith (see Map 1). Botha had at his disposal 4 500 burghers, four guns and a pom-pom. General Buller commanded a reinforced division of 20 000 officers and men, with 44 guns. Yet so skilfully did Botha lay his ambush that on 15th December 1899 Buller stumbled blindly in to it - or, more correctly, marched into it with open eyes in broad daylight.

General Botha on Dopper, Glencoe, March 1900

The results for Buller and his army were, of course, disastrous. He withdrew from the battlefield having suffered more than 1 300 casualties (according to his own returns) and abandoning intact 10 field guns and 12 fully loaded ammunition wagons. Two days after the battle Buller was superseded as British Commander-in-Chief, South Africa, by Field Marshal Lord Roberts. He remained, however, commander of the British forces in Natal, and therefore Botha's adversary in the subsequent battles of the Tugela line.

Despite his remarkable victory at Colenso, Botha's force was not nearly strong enough to destroy Buller's army. Nor, with most of the Boer commandos in Natal tied up in the futile siege of Ladysmith, could he wrest the initiative from the enemy. Safely out of harm's way at Chieveley and Frere, Buller could recover his composure and rebuild his army, and there was nothing Botha could do in the circumstances but to prepare for the resumption of the British offensive.

At the beginning of January 1900, President Kruger in fact made an attempt to break the stalemate. He ordered an all-out attack on the commanding feature of Platrand (i.e. Caesar's Camp and Wagon Hill), a vital sector in the British defences round Ladysmith (see Map 1). In this way the President hoped that the fortress might be reduced and the investing commandos released for offensive operations in Southern Natal and on the western front south of Kimberley. But the ailing Commandant-General Piet Joubert and his indifferent deputy, General Schalk Burger made an awful hash of the attack. They shamefully sacrified the heroic vanguard of the assault column - a handful of Free Staters and Transvalers who in the early morning hours of 6th January 1900 reached the crest line of Platrand and came within a toucher of occupying the ridge and tearing a gap in the defence perimeter.

By this time Buller's army had been reinforced by the arrival of the 5th Division under Lieut-General Sir Charles Warren to more than 30 000 officers and men, with 66 guns. General Warren, a self-assured and eccentric veteran of 59, did not exactly endear himself to his commander by his outspoken criticism of Buller's inaction since the battle of Colenso. When he suggested that the next attack should be directed towards Hlangwane Hill, which was indeed the weak link in the Colenso defences, Buller cut him short. "What do you know about it?" he asked. Buller had already decided to by-pass the Colenso position by moving the bulk of his army some 20 miles up-stream and breaking through to Ladysmith in a wide outflanking movement.

The move began on 10th January 1900 after two days of incessant rain. The downpour had turned the countryside into a quagmire and every spruit into a torrent. Leaving one brigade and four naval guns at Chieveley to mask the Colenso position, Buller ploughed and slithered westwards across the sodden plain with the rest of his army - 24 000 men with 58 guns, accompanied by huge ammunition and supply columns. It took him six days to concentrate at his forward base - Springfield, 16 miles to the west - and build up supplies for 16 days (see Map 1). The slow, clumsy (procession precluded the possibility of surprise and confirmed the following opinion on Buller by one of his staff officers: "He took care that supplies were abundant, but often, and to his cost and ours, placed supply before strategy at critical moments."

Buller's plan for the break-through, very briefly, was as follows: Major-General Lyttelton was to cross the Tugela River at Potgieter's Drift with two infantry brigades, a howitzer battery and a field battery (altogether approximately 9 000 men and 12 guns) to carry out a holding operation against the Boers in the arc of hills facing the northward loops in the river. General Warren was to cross at Trichardt's Drift, five miles up-stream, with three infantry brigades, a mounted brigade and six batteries of field artillery (altogether 15 000 men and 36 guns). He was to work his way round the great barrier of hills to the west of Spioenkop - the Tabanyama range - in order to turn the Boer flank which Buller believed rested on Bastion Hill. Then, having reached the Acton Homes area, he was to advance along the road over the undulating plain towards Ladysmith in rear of the hills. Lyttelton began to cross the river in the early hours of 17th January and Warren later in the day (see Map 2).

Warren's troops crossing pontoon bridge at Trichardt's Drift, 17th January, 1900.

After the battle of Colenso General Botha, as I have said, prepared for the next British attack. He believed that this attack would again be launched in the Colenso sector - because of its proximity to the railway and its vulnerability to a turning movement on his left, towards Hlangwane Hill and the ridges further to the east. Towards the end of December 1899 he became indisposed - exhausted, as he put it, by the tension and anxiety of the previous weeks and by pressure of work, day and night (and, he might have added, under constant shell-fire). When his former chief, General Lucas Meyer, returned to Colenso at the beginning of January 1900 after two months' medical treatment in Pretoria, Botha hoped that he would now be able to take a short period of leave. This was the state of affairs when General Buller began his march towards the Upper Tugela.

The Boers in the area at that time numbered only 1 000 - 500 Free Staters with one gun under General Andries Cronje at Brakfontein, facing Potgieter's Drift, and 500 Johannesburgers at Porrit's Drift (see Map 1). Reporting the British move to General Joubert, Botha stressed the urgency of sending reinforcements to the Upper Tugela from Ladysmith. Reinforcements from his own front at Colenso left during the night. The next few days, from 11th January onwards, were a period of feverish activity for Botha. Early in the mornings, long before daybreak, he left his headquarters at Colenso for the threatened sector, a ride of three and a half hours on horseback. There he supervised the construction of defences in the Brakfontein area, since it was expected that the British would attack by way of Potgieter's Drift. In the evenings after sunset he returned again to Colenso to organize the dispatch of additional reinforcements, ammunition and supplies, and to dictate his reports to President Kruger and General Joubert.

He did not move his headquarters to the Upper Tugela because he still hoped to be able to get away on leave before the impending attack. When, however, he mentioned his indisposition in one of his reports, hinting that either General Schalk Burger or General Daniel Erasmus be put in command on the Upper Tugela, and later expressing a wish to take a few days of leave, President Kruger intervened. He indicated in no uncertain manner that he wanted Botha to take command on the new front at all costs. Here, the President said, every man would have to fight to the limit. In a telegram to Botha he requested him - "respectfully" - not to insist on leave until the battle had been fought. ,,Ik beschouw dat uwe tegenwoordigheid onder deze moeilijke omstandigheden ten uwent onmisbaar is", he said, "God zal u helpen en ondersteunen in uwe moeilijke taak." ("I regard your presence in the difficult circumstances on your front as indispensable. God will help and sustain you in your onerous task").

That, as far as Botha was concerned, was that. He left for the Upper Tugela on the morning of 16th January. The Boer forces in the area had by that time been reinforced to approximately 4 000 men with four 75 mm field guns and two pom-poms (to oppose, as you will remember, an army of 24 000 men with 58 guns). Moreover the commandos were deployed (from the Twin Peaks to Doringkop) in anticipation of an attack through Potgieter's Drift and possibly Munger's Drift and Skiet Drift (see Maps 1 and 2). The news that Botha had arrived to take command was received with great satisfaction by officers and men alike. As one burgher put it, "it was a relief - one felt as if a weight of doubt and care and anxiety had been taken from the mind."

Botha spent the night in General Tobias Smuts's camp behind Vaalkrans, still feeling ill. The next morning dawned wet and foggy after overnight rain, but from the lower slopes of the hills General Lyttelton's troops, who had crossed the river during the night, could be seen in the koppies north of Potgieter's Drift. At 5 a.m. Lyttelton's howitzers, supported by 10 long-range naval guns in the commanding hills south of the river, opened fire - a bombardment which was to continue for the next seven days. At 8 o'clock Botha rode over to General Schalk Burger's headquarters, concerned about his right flank which was hanging dangerously in the air. It was here that he learnt about the crossings at Trichardt's Drift, where General Warren was at that moment moving the greater part of Buller's army to the north bank of the Tugela. Apart from a picket of 500 Free Staters and Pretoria burghers in the so- called Wapadnek (Wagon Road Pass) west of Spioenkop, the Tabanyama range was completely defenceless. Five hundred men against an army of 15 000 supported by 36 guns.

Although deeply concerned about the ominous turn of events, Botha now staked everything on his hope that the British generals would lack the boldness for an immediate advance. During the afternoon he returned all the way to Colenso to prize out further reinforcements from the already tenuous lines on that front. That night he was so exhausted that he had to make his arrangements and dictate his dispatches lying down. But on his return to the Upper Tugela the next day (18th January) his hope had been fulfilled.

General Warren believed there were thousands of Boers in the hills ahead of him. He had no intention of advancing before having crossed the river with his entire force and all his guns and wagons - a procession of 15 miles with 15 000 oxen. The crossing was completed only after three days, and by that time he had concluded that the outflanking march by way of Acton Homes, which Buller had ordered, was unfeasible. The route, he considered, was too long for his huge baggage train, without which it was unthinkable for him to move. He chose instead the direct route through the Wapadnek and ordered a frontal attack on the Tabanyama range the next morning - 20th January - to clear the way. Lord Dundonald who had ranged ahead to the Acton Homes area with his mounted brigade and had ambushed there a Boer patrol, was recalled - to Dundonald's intense annoyance.

These plodding manoeuvres suited Botha admirably. They enabled him to extend his front for seven miles along the Tabanyama range and beyond the road near Acton Homes. On this front Botha had at his disposal only 1 800 men, three 75 mm field guns and a pom-pom. But the positions he selected in consultation with his officers showed once again what a skilful tactician he was. From the British vantage points in the Tugela valley only the forward crests of Tabanyama (from Piquet Hill to Bastion Hill) were visible. The real crest of the range, however, lay 600 to 2 000 yards further back. It was along this crest, out of sight of the enemy and with a good field of fire over the gentle slopes to the forward crests, that Botha ordered his burghers to dig in (see Map 3). The future General Jan Kemp, who was one of Botha's field-cornets on Tabanyama, later commented: ,,Al moet ek dit self sê, ons offisiere het darem goed geweet wat hulle doen toe hulle die stellings gekies het." ("Though I have to say it myself, our officers certainly knew what they were doing when they selected those positions.")

The attack on Tabanyama began at 3 a.m. on Saturday, 20th January 1900. Major-General Woodgate's 11th (or Lancashire) Brigade led the climb up the steep slopes to the forward crests, followed by Major-General Hart's 5th (or Irish) Brigade. Since these slopes were dead ground to the Boers, the troops reached the crests in three hours virtually without opposition. The real crest of the range was now revealed to General Warren, and he realized that the Boers were entrenched along it. After his field batteries had been brought forward to Three Tree Hill, Warren opened up against the hills ahead of him with his 36 fifteen-pounders. When the barrage had been kept up for four hours, General Hart began to advance beyond the southern crests with four and a half battalions - Lancashire Fusiliers, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, the Border Regiment, and York and Lancaster Regiment.

As the battalions advanced within rifle range Botha's burghers responded with their usual deadly Mauser fire. An officer of the Lancashire Fusiliers described the further course of the attack as follows: "Before long, owing to the roughness of the surface, to fatigue and faint heart, the line became disordered, and an uncontrollable tendency asserted itself to collect in pockets on the ground for shelter, for breathing space, and for the summoning of resolution for further advance. On the first few occasions the halt was momentary, but the impulse to linger ever grew until finally, as the sense of physical danger overpowered the mental resolve, and as the hills loomed more threateningly ahead, the laggard progress stopped for good and all, and the tired and dispirited attackers longed only for dark."

The infantry had been checked and pinned, and after dark they withdrew below the southern crests. That night the Boers, tired as they were, continued to work on their defences. They watched the lanterns of the British ambulances and medical personnel collecting the dead and wounded. To guard against a possible night attack the burghers occasionally fired short bursts with their Mausers and shot up flares to light the slopes. The next morning - Sunday, 21st January - General Warren, who had by this time lined the southern crests with all three of his infantry brigades and his mounted brigade, now dismounted, resumed the attack with heavy artillery support. The troops were again repulsed. But Botha's burghers were beginning to show signs of wavering as more shells hit the entrenchments, blasting them away, killing and maiming. The well-known Free State chaplain, the Rev. J. D. Kestell, gave an account of Botha's conduct on this day in his memoirs.

"I visited the battlefield ... on Sunday, January 21, when the bombardment was at its fiercest", wrote Kestell. "I found that it had often been so intolerable that the burghers were driven out of the earthworks and compelled to seek shelter behind the hill slopes. But they had always returned and kept up a continuous fire on the advancing soldiers. I found, too, that the English had as yet always been driven back, but that their repeated attacks had not had quite a satisfactory moral effect on the burghers. The direction of affairs was, however, in the hands of ... General Louis Botha, than whom there was no man better qualified to encourage the burghers. Just as at Colenso, so here he rode from position to position, and whenever burghers - as I have related - were losing heart and on the point of giving way under the awful bombardment, he would appear as if from nowhere and contrive to get them back into the positions by 'gentle persuasion', as he expressed it, or by other means."

General Warren did not attempt another assault the following day - Monday, 22nd January - but the artillery fire continued and clouds of dust and lyddite fumes rose over the hills. Botha reported that burghers were leaving the front in larger numbers than reinforcements were arriving. He himself had a narrow shave when his horse was shot under him. Warren's troops were reinforced in the morning by another infantry brigade and four howitzers to more than 18 000 men and 40 guns. His force now outnumbered Botha's by ten to one in men and artillery, yet it was the British generals who were forced by the strain of battle to take an ill-considered step.

All this time General Buller had been watching Warren's operations from his headquarters on Mount Alice, as the Times History put it, like an impartial umpire at manoeuvres. He had allowed Warren to convert his original plan to turn the Boer flank into a frontal attack. When he visited Warren and learnt that he now proposed to demoralize the Boers by three or four days' continuous shelling, Buller would not hear of it. During the past six days Warren had achieved nothing and Buller now, understandably, insisted on results, otherwise, he said, he would withdraw Warren's force back across the Tugela. Warren replied that he could only push through the Wapadnek after having taken Spioenkop first, whereupon Buller was said to have commented irritably: "Of course you must take Spioenkop."

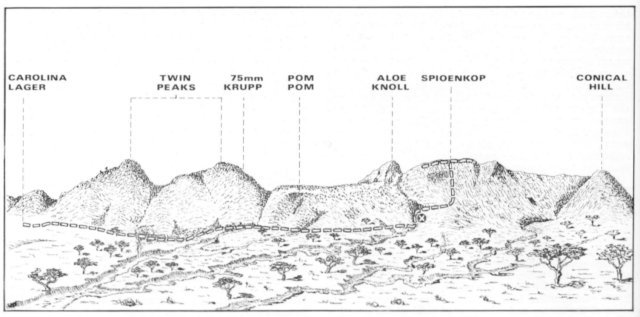

Sketch of Spioenkop and the range of hills to the east of it as seen from the

Boer side (i.e. from the north). Note the positions of the Krupp gun and Pom-Pom which

were hauled up the slope on the morning of 24th January, 1900 to support the

counter-attack on Spioenkop by Cmdt. Prinsloo and his burghers. The dotted lines show

Prinsloo's route and the position his men took up along the crest line. They left their

horses in the gully marked "X" and then climbed the hill.

(Drawn in 1939 by I.J. de Villiers, a grandson of Cmdt. Prinsloo)

And so it was decided to occupy this commanding hill, its flat, rocky summit rising 1 470 feet above the Tugela. To Warren the operation was to be merely the first step in the resumption of his attack on Tabanyama, and simultaneously a safeguard against a humiliating withdrawal. To Buller it was a means of getting Warren to take some action. When Buller told one of his staff officers to accompany the assault force to Spioenkop, the latter asked him what the force was to do when it had taken the hill. Buller thought for a moment and replied: "It has got to stay there." The attackers therefore were simply to establish themselves on the hill. There was to be no attack elsewhere along the front to support them. The rest of Buller's army was to look on and do nothing. That Botha with 1 800 men and a few guns was able to force Buller and Warren into such a haphazard operation was certainly no small achievement.

The force to capture Spioenkop was commanded by General Woodgate and consisted of the Lancashire Fusiliers, six companies of the Royal Lancasters and two of the South Lancashires, Thorneycroft's mounted infantry and half a company of Royal Engineers, altogether approximately 1 700 officers and men. The column marched off from its rendezvous, a gully south of Three Tree Hill, at 8.30 on the night of 23rd January. At 11 o'clock the ascent began, in single file up the south-western spur of the hill with Colonel Thorneycroft leading. Towards 3 o'clock in the morning - Wednesday, 24th January 1900 - as the spur widened towards the summit, the troops deployed in the damp grass in pitch darkness (see Map 3).

Spioenkop was held that night by a detachment of some 50 Vryheid burghers and German volunteers. They had apparently gone to sleep after having completed an emplacement for a 75 mm field gun which Botha had intended positioning on the hill the next morning. A few pickets near the top of the spur woke up from the shuffling ahead of them. There was a loud "Werda!" followed by a burst of rifle fire. Then the troops came in at the point of the bayonet, amid shouts of "Majuba!", "Bronkhorstspruit!". The pickets turned and fled, shouting "Hardloop burgers, die Engelse is op die kop!" One man was bayonetted. The rest, instinctively grabbing their rifles and bandoliers, made good their escape. Having captured the summit, the troops gave three cheers. The waiting gunners on Three Tree Hill responded by shooting a star shell into the air. Then the batteries opened up against the approaches to Spioenkop in an effort to prevent the Boers from recapturing the hill.

It was now approximately 4 o'clock. The crests of Spioenkop and the other hills in the area were shrouded in dense fog. The engineers taped out a position for a trench along what appeared to them to be the northern crest line of the (roughly) 400 square yard summit of Spioenkop. In fact the position was 50 to 200 yards short of the crest line. Moreover it was virtually impossible to entrench on the rocky hilltop and the trenches together with their stone parapets were nowhere deeper than two and a half to three feet.

Meanwhile the Vryheid burghers had arrived breathless and confused at Botha's tent on the koppie to the north of Spioenkop with the tidings of what had happened. It is not recorded what he told them. In circumstances such as these Botha was a cool, calm and unshakeable commander. Spioenkop simply had to be recaptured. By this time the alarm had also been given in the Carolina and Lydenburg laager, where General Schalk Burger had spent the night. Burger ordered the Carolina commandant Hendrik Prinsloo, one of the finest officers in the Boer forces, to storm the hill with a detachment of his men. Botha was informed of this instruction. There is evidence that Prinsloo galloped to Botha's headquarters to discuss the situation and receive his final orders. Botha agreed to reinforce Prinsloo's attack from Tabanyama and to support it with rifle and artillery fire.

Before starting his climb Prinsloo, in accordance with Botha's orders, arranged for covering fire from his rear. A 75 mm Krupp field gun and a pom-pom were hauled on to the ridges east of Spioenkop and a detachment of 50 burghers was placed on Aloe Knoll, a prominent feature at the apex of the eastern spur of the hill. Shortly after 7 o'clock Prinsloo and approximately 65 Carolina men (later reinforced to 84) reached a point some distance below the north-eastern summit of Spioenkop (see sketch). Here Prinsloo addressed them in the mist as follows: "Burgers, ons gaan onder die vyand in en ons sal nie almal terugkom nie. Doen julle plig en vertrou op die Here." ("Burghers, we are going in amongst the enemy and all of us will not return. Do your duty and trust in the Lord.") Then he dispersed them and led them to the summit, the men moving warily from rock to rock like hunters stalking their prey.

Along the crest line they bumped detachments of Woodgate's troops who had pushed forward when it was discovered (as the mist thinned out slightly) that the main trench had been incorrectly sited. Fierce fighting ensued and the battle of Spioenkop was under way. Here and there the exchanges were hand-to-hand, with burghers wrenching rifles from the hands of the soldiers. There were grievous casualties on both sides in the point-blank shooting and the Mauser and Lee-Metford fire formed a cloud in the mist. When the fog lifted suddenly between 8 o'clock and 8.30, a storm of bullets lashed the summit of Spioenkop from the hills on all sides of it - from the western Twin Peak, Aloe Knoll, Conical Hill and Green Hill, where the burghers had been waiting with finger on the trigger.

Now that the sun had broken through, Prinsloo, who had stationed a heliographer - a young fellow named Louis Bothma - on the slope below the summit, was able to give Botha his first situation report. Botha signalled back that more men were on their way and that Spioenkop must be held at all costs. The Boer artillery was thereupon informed of the position of Prinsloo's men along the crest line and soon the shells were raking the overcrowded summit with deadly accuracy. Botha's artillery consisted of two 75 mm Creusot field guns, one 75 mm Krupp field gun and a pom-pom on Tabanyama, a 75 mm Krupp field gun on the koppie from where Botha commanded the operation, and the Krupp 75 and pom-pom on the ridges to the east of Spioenkop - altogether only five guns and two pom-poms (see Map 3). These pieces were as skilfully sited as they were served. The British artillery - 58 guns on the whole Upper Tugela front, as you will remember - tried in vain to locate and silence them. In no other action in the Anglo-Boer War did the Boer artillery wreak greater havoc than Botha's handful of guns on this day.

By about 9.30, when Prinsloo's burghers had borne the brunt of the fighting on Spioenkop for two hours, the first reinforcements arrived, mainly Pretoria men under Commandant "Red" Daniel Opperman. Gradually the surviving British troops on the crest line were driven back to the trenches, having suffered heavy casualties. Two desperate charges from the main trench were beaten off. But the Boer losses were also severe and their dead lay hideously where they had fallen. According to Deneys Reitz, it was only "Red" Daniel Opperman's forceful personality and vigorous language to anyone who seemed to be wavering that kept the burghers in check in his sector. At about 1 o'clock in the afternoon a detachment of Lancashire Fusiliers on the eastern side of the summit waved their handkerchiefs in the air in token of surrender. The Boer fire stopped and a few Pretoria burghers jumped over the British parapets, shouting to the troops in the vicinity to give themselves up. Colonel Thorneycroft then appeared on the scene, saying there was no surrender, and as the British rifle fire resumed the Pretoria men darted back for shelter accompanied by approximately 170 prisoners.

After this sign of wavering in the enemy's ranks, Botha ordered the artillery and rifle fire on the summit to be increased. Thanks to the efforts of Prinsloo and Bothma, and of Botha's scouts and dispatch riders, he was well aware of what was happening on Spioenkop and Thabanyama. The Carolina and Pretoria burghers on Spioenkop were reinforced during the day by detachments from several commandos - Krugersdorpers under Oosthuizen and Kemp and German volunteers from Thabanyama; Ermelo and Standerton men under Tobias Smuts and Johannesburgers from the Vaalkrans area. Botha, however, was careful not to put all available reinforcements on Spioenkop. He said later that his men on the hill never exceeded 350. He knew how to deploy his burghers to obtain the best tactical results. In particular, he reinforced Green Hill, whence the south-western spur of Spioenkop, the British line of approach to the summit, could also be kept under fire.

On the other hand there was great confusion on the British side. Woodgate, the commander of the assault column, was mortally wounded early in the fight. Colonel Crofton of the South Lancashires informed Warren of this development in a message which reached him as follows: "Reinforce at once or all is lost. General dead." Warren, who had earlier been told that Woodgate's force could hold on "till Doomsday", never recovered from this shock. His only idea was to send more and more reinforcements to Spioenkop. It does not seem to have occurred to him that he could be of greater assistance to the troops on the summit by launching a diversionary attack across Tabanyama, where on a three-mile front he had over 10 000 men facing barely 1 500 Boers. Altogether four additional battalions and two squadrons of mounted infantry were ordered to the summit, bringing the total number of troops sent there to 4 500. The entrenchments on the hill were choked, not only with fighting soldiers but with hundreds of dead, dying, maimed and cowering non-fighters. In these conditions Botha's artillery and marksmen exacted an appalling toll. Throughout the day there was a serious breakdown in communications with the summit. The only British heliograph on Spioenkop was shot to pieces early in the morning, and by nightfall Buller and Warren were still unaware of the great debAcle that was threatening on the hill.

Late in the afternoon one of Lyttelton's battalions, the King's Royal Rifles, captured the Twin Peaks, to the east of Spioenkop, after a gallant climb up the steep slopes (see Map 3). The Boer Krupp gun and pom-pom had to be hastily withdrawn and the Lydenburg and Carolina burghers who had held the peaks, galloped away across the plain. Botha's line had now been breached, at a loss to the Rifles of approximately 100 casualties including their commander (Buchanan-Riddle), who had been killed. But Buller did not realize that the battalion had presented him with an opportunity to win the day. On the contrary, he was disturbed because he considered that Lyttelton's troops were too widely dispersed. Consequently he ordered the battalion to withdraw after dark. The troops began to leave the peaks at about the time the Utrecht burghers, whom Botha had called over post-haste from Green Hill, arrived at the foot of the hills to begin another counter-attack.

The fighting on Spioenkop gradually died down after nightfall. The din of battle gave way to an eerie silence. Behind the British breastworks the burghers could hear men talking and stumbling about in the darkness, and above all the moans and cries of the wounded. Most of the burghers - some of whom, like the survivors of Prinsloo's original assault force, had been on the summit for more than 12 hours - now began to descend the hill. All of them were exhausted, and many were uncertain about what they were to do and apprehensive of the morrow's prospects. (Commandant Prinsloo was absent at this stage. He had had the painful task after dark of carrying the body of his fallen brother, Willie, off the hill).

Botha knew that the burghers were descending the hill in considerable numbers, but he was not concerned about it. They needed rest, water and food after the day's experiences. In any case he was convinced that the battle had already been won. The British inaction on Tabanyama, their strange hesitation after capturing the Twin Peaks, and the resignation with which they endured their punishment on Spioenkop led him to only one conclusion: that they would withdraw during the night. This he explained in his official dispatch to President Kruger, adding that he would nevertheless take no risk. He would make the necessary preparations in case the battle would have to be resumed the next morning.

British dead in main trench, Spioenkop, 25th January, 1900.

Botha's military secretary, Sandberg, says in his memoirs that he and Botha were so tired that they dozed off more than once while working on this dispatch. But there was to be little rest for Botha during that night. From General Schalk Burger he received the advice that further resistance was futile because the attenuated Boer forces could no longer hold the front. Botha thereupon drafted a written reply in which he seriously urged Burger on no account to lose heart or abandon his positions. "Let us fight and die together", he pleaded, "but, brother, please do not let us yield an inch to the English." Botha went on to express the opinion that the enemy was now so timorous ("kopsku") that if the Boers remained faithful and steadfast he would submit. "I am confident and convinced", he said, "that if only we stand firm our Lord will give us victory."(1)

Towards midnight the dispatch rider who had to deliver this message returned, accompanied by Commandant Prinsloo, with the news that Schalk Burger had indeed pulled out and was in full retreat towards Ladysmith with his Lydenburgers and a number of Carolina burghers. Botha and Prinsloo hurried over to the Carolina laager, which they found in great confusion. Wagons had been packed and horsemen were getting ready to move off in the wake of Burger's flight. Botha addressed the men from the saddle, telling them (as Deneys Reitz puts it) of the shame that would be theirs if they deserted their posts in this hour of danger. He succeeded in rallying them and the men filed back in the dark towards Spioenkop. Later Botha also ordered a detachment of Heidelbergers from Tabanyama to Spioenkop and assembled a fresh assault force at the foot of the hill.

Meanwhile the British evacuation of Spioenkop, which Botha had expected and prophesied, had occurred. By 10 o'clock that night Colonel Thorneycroft, whom Buller had put in command on the hill during the day, had received no communication from his commanding generals except the news of his appointment. He did not know what, if anything, was contemplated to assist him. His men, he knew only too well, could not stand another day's pounding by the Boer artillery, nor would he allow them to remain merely a defenceless target for the Boer gunners. He therefore ordered a withdrawal. "Better six battalions safely off the hill than a mop-up in the morning," he explained to Winston Churchill, whom he met on his way down the hill. The dead and scores of wounded were left behind on the summit, many of the latter to die from exposure.

British medical orderlies and Boers amongst the fallen, Spioenkop, 25th January, 1900.

Jan Kemp was the first Boer officer to discover at daybreak the next morning - Thursday, 25th January 1900 - that the British had abandoned Spioenkop. Throughout the night he had remained high up on the slopes with a detachment of Krugersdorpers. Despite the gruesome sights of the summit, Kemp could not resist (as he said later) thinking of the "ribbons and medals" a British officer would have received in similar circumstances. On the crest line the burghers held aloft their rifles and waved with their hats to indicate to their comrades below that the enemy had retired. Hundreds of burghers then began to scale the slopes. Botha soon arrived on the summit with members of his staff. He spoke briefly to the British chaplain and medical officers who had come up to attend to the wounded who had survived the night. He ordered his burghers to give them every assistance and gave instructions that coffee should be brought to them from his camp. On his return to his headquarters he sent the following telegram to President Kruger and General Joubert:

"Battle over and by the grace of God a magnificent victory for us. The enemy driven out of their positions and their losses are great. At least 600 dead and a large number of wounded are still lying on the battlefield. The enemy have asked me to remove their wounded and bury their dead, to which I have agreed. The battlefield therefore is ours. Last night the enemy withdrew some distance with their guns and soldiers. Furthermore 187 prisoners were taken ... It breaks my heart to say that so many of our gallant heroes have also been killed and wounded. The names will be telegraphed to you later. It is incredible that such a small handful of men, with the help of the Most High, could fight and withstand the mighty Britain for six consecutive days and drive them back on the last day with heavy loss. We have taken approximately 40 cases of Lee-Metford cartridges and a good number of rifles."(2)

Commandant Willem Pretorius of Heidelberg whom Botha had ordered to count the British dead on the summit, reported that there were 650. In addition there remained on the hill 350 seriously wounded soldiers, most of them beyond hope of recovery. In the light of these figures, the official British casualty list for Spioenkop - 68 officers and 976 men - does not appear to be complete. The Boer casualties for the whole Upper Tugela front on 24th January were 59 killed in action, nine died of wounds and 134 wounded. Of Prinsloo's detachment of 84 Carolina burghers, more than 50 were killed or wounded.

After nightfall on 25th January, Warren's force began to withdraw from the north bank of the Tugela. The withdrawal continued throughout the next day and night, often in pouring rain - the extraordinary sight of an army of 20 000 officers and men with 36 field guns and four howitzers retreating before approximately 1 800 Boers. Botha did not harass the withdrawal because he considered his men had had enough. By Saturday, 27th January 1900, Warren's troops were back in their camps near Springfield, which they had left 10 days before. "The net result is that we have once more to chronicle a complete defeat", wrote General Hart of the 5th (or Irish Brigade) in a private letter; and the future Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff towards the end of the First World War, noted in his diary: "We stand where we did 10 days ago, with a licking thrown in." The total British casualties during these days were officially given as 1 750. The Boer casualties were 335.

There is no doubt that in tactical skill Botha proved more than a match for the wavering and slow-witted Generals Buller and Warren in the Spioenkop campaign. But it was particularly his resolution and iron will which enabled him to outclass them as a military commander and, with a small handful of burghers, to inflict upon the British army another heavy defeat.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org