The South African

The South African

by ARTHUR BLAKE - (Illustrated by ROBERT H. WISHART)

EDITOR'S NOTE:

This article is the second in a series covering aircraft flown by the

South African Air Force. Initially the series will deal with the aircraft

on exhibition at this Museum. Thereafter an attempt will be made to

deal with all military aircraft manufactured in South Africa and later,

it is hoped, take in all those that have seen service in the S.A. Air Force.

Several South Africans who won fame as 'scout' (later known as 'fighter') pilots in the First World War flew the S.E. 5a. It is therefore fitting that the aircraft was chosen as the SAAF's first fighter aircraft and that an S.E. 5a has been preserved in the South African National War Museum.

The history of the aircraft during the First World War has two trends - one of trials and tribulations on the ground; the other of success in the sky. The technical side of the story has a strange international flavour starting in Barcelona, Spain, shortly after the outbreak of hostilities in August, 1914. The brilliant Swiss engineer, Marc Birkigt, set aside his work of producing high-quality Hispano-Suiza motor vehicles to design an engine suitable for use in aircraft. He realised that the engine as the source of power dominated the development of the aircraft. However brilliant a design was, it was doomed to failure without a proper power plant.

At the time more and more people were realising the potential of aircraft as a weapon. The types then in use were powered mostly by two basic types of engine: the now almost forgotten rotary type and the water-cooled inline type inherited from the development of the motorcar. However, both were unsatisfactory. The inline types were mostly heavy clumsy affairs whose weight ate into the aircraft's ability to climb to the increasing altitudes made necessary by the war, its speed and the load of crew, weapons and fuel. The rotary with its stationary crankcase and whirling cylinders was used in many designs as its ratio of engine weight to horsepower produced was good, some 3,5 lbs. of engine weight being needed to produce one horsepower. The snag with the rotary was that it was an extravagant fuel guzzler whose appetite had to be satisfied with heavy fuel loads which in turn cancelled out the economy in engine weight. Besides this, the rotary was a temperamental piece of machinery inclined to seize or disintegrate in a spectacular shower of debris.

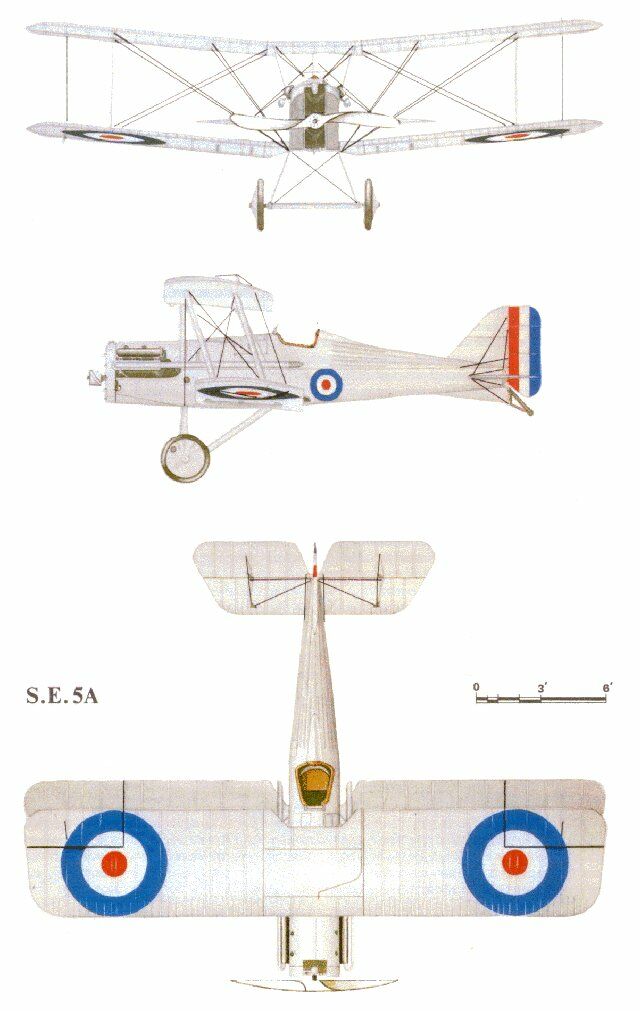

S.E. 5a.

He slashed pounds off the weight of the engine and stepped up the horsepower output by increasing the compression rate of the engine. Using his Mono Bloc system to cast the then relatively little-used metal, aluminium, he produced cylinders, cylinder heads and water jackets which were lighter yet stronger than steel. Where necessary, steel liners were screwed in. An added advantage of using aluminium was the metal's high heat conductivity. This made the engine easier to cool than its steel or cast iron counterparts.

In July 1915, the novel design attracted the attention of the French and an engine was obtained from neutral Spain. A series of satisfactory bench tests followed and after the conclusion of licence negotiations, the 150 h.p. Hispano Suiza entered production in France. Early in 1916 one of the French-built engines reached Britain.

The staff of Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, designed three day fighters around the new engine. One of them - the F.E. 10 - was a weird contraption with the pilot sitting in front of the propeller. The others were the more conventional F.E. 9 and S.E. 5 (Scout Experimental Five). This bi-plane was the product of the design team consisting of H. P. Folland and J. Kenworthy. It was powered by the 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza and was armed with one Vickers .303 machine gun in the fuselage and a Lewis .303 gun on a special Foster mounting above the centre section. Much development work, modification and a fatal crash followed. Some of the aircraft were sent to France, where the S.E. 5 gave a good account of itself. After 59 aircraft were built, production was halted in favour of the S.E. 5a.

The new S.E. 5a was basically similar to the earlier aircraft. It differed mainly in being fitted with 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza 8B, 8C, 8D and 8E engines and in its shorter wing span. Orders for 3 600 aircraft were placed in 1917 and it entered service by June 1917. The engines came from three sources. These were the Brasier concern in France, Wolseley Motors of Birmingham and various other factories in France. The Brasier-built engines gave a lot of trouble and faulty reduction gears and airscrew shafts had to be replaced. Wolseley also had their problems, but the other French engines were satisfactory. In curing the teething troubles, Wolseley introduced several modifications and called the new engine the Viper. It gave satisfactory service and the SAAF's aircraft were fitted with them.

The S.E. 5a was soon very popular with pilots. They found the aircraft strong, manoeuvrable, and stable. It held its own until the Armistice when 14 British, one Australian and two American squadrons in France were equipped with the S.E. 5a. Other British squadrons in Palestine, Greece and Mesopotamia also used the aircraft. Home Defence units in Britain discarded it as the water-cooled engine took too long to warm up before a mission.

Another South African ace who flew the S.E. 5a was Captain C. J. Venter (later Maj. Gen., CB, DFC and bar) who served with No.29 Squadron RFC/RAF. He destroyed 22 enemy aircraft. Captain H. Meintjies flew an S.E. 5 at one stage. This was A 8900. Of the great British aces, Major E. Mannock, VC, DSO (2 bars), MC (bar), (73 victories), Lt. Col. W. A. Bishop, VC, DSO(bar), MC, DFC (72 victories), and Major J. T. B. McCudden, VC, DSO(bar), MC(bar), MM, (57 victories) all flew the S.E. 5a at some stage or another.

After the war, the S.E. 5a was one of the types selected for the "Imperial Gift" of aircraft sent to South Africa to form a permanent Air Force. Although the 22 S.E. 5a's formed a considerable part of the 110 aircraft taken on charge at Zwartkop, the fighter was destined to play a comparatively minor role during the formative years of the SAAF. It was overshadowed by the DH-9 and DH-4 Recce/Bombers and the Avro 504K trainers.

The 1921 establishment of the SAAF called for an S.E. 5a flight of six aircraft for ground attacks and air fighting. This flight did not become a reality. At the time financial resources were limited and each aircraft was stripped and completely overhauled before use, a process which lasted six weeks. The S.E. 5a had a low priority but in the process shed its wartime camouflage and British serial number. In their place came the SAAF silver overall finish and a new serial number in the range between 300 and 321. The overhauling of the S.E. 5a's was further delayed when all available resources had to be used to maintain the other types used during the Rand Rebellion and early operations in South West Africa.

By 1923, the SAAF had 26 aircraft in service, of which only two were S.E. 5a's. Although a cadre of an operational squadron existed with a fighter flight as part of the establishment, the SAAF's striking arm in fact consisted of a single mixed flight. The next year the number of available aircraft had increased to 33, but only a single S.E. 5a was in use at Zwartkop. Two had been written off, while a further 18 were held in storage.

It was not until 1925 that a decision was taken to overhaul

and use the fighters in storage. This was done to save

the wear and tear on the DH-4 and DH-9 then bearing the

brunt of flying. The S.E. 5a was to be used for advanced

flying training to save the SAAF's meagre resources and to

delay the purchase of new aircraft for the next three years.

The overhauling programme was completed in less than

two years with the statistics for 1926 being one aircraft in

service, two in the Reserve Park, 10 in the workshops and

eight in store.

Much donkey work lay ahead for the S.E. 5a. Members of the Permanent Force, the General Reserve and the new Special Reserve flew the fighter for many hours during training. By 1928, five had been written off and another four repaired. While attrition was taking its toll, plans were underway to modernise the SAAF. New engines were fitted to old aim-frames followed by the purchase and later licence production of newer types. The "Old Soldier" didn't die; it just faded away out of service.

In this process it was realised that the air-frame was obsolete, but an effort was made to keep Marc Birkigt's engine in service for a bit longer. The Viper was built into a DH-9 air-frame but the results were poor.

The S.E. 5a's place as the SAAF's fighter was taken to a certain extent by the M'pala 1, a Bristol Jupiter VIII-engined version of the DH-9. It was not until the arrival of the Hawker Fury in the middle-thirties that the SAAF had a modern fighter on strength.

CONSTRUCTION:

The fuselage was a spruce box-girder structure braced

with piano wire. It was fabric-covered except for plywood

sides from the nose to the front spar of the lower wing and

round the cockpit. The main fuel tank was behind the

engine and there was a gravity tank to port of the centre

section. The undercarriage consisted of two sets of wooden

V-struts with a spreader bar between the wheels. A head-rest

was fitted behind the cockpit. The tail plane incidence

could be changed in flight. Spruce was also used in the wing

structure which consisted of wire braced spars some of

which were solid.

The basic statistics of the type were:

ENGINE:

One 200 h.p. V-type Wolseley Viper driving a two-blade

airscrew. Two exhaust pipes ran along the sides of the

fuselage to a point next to the cockpit. The aircraft had a

top speed of 137.8 m.p.h. at ground level and it could

climb to 5 000 feet in just under five minutes.

ARMAMENT:

A fixed .303 Vickers machine gun fired through the

propeller arc by means of the Constantinesco CC synchronising

gear. The weapon was aimed by an Aldis or a ring

and bead sight and was fitted with a Hyland type E loading

handle and Fitzgerald jam clearers. The machine gun was

belt-led. A Lewis .303 machine gun was fitted on the top

surface of the top wing by means of a Foster mounting. This

enabled the gun to be fired straight ahead outside the

propeller arc or straight up. For loading, the breech could

be reached by sliding the gun on the mounting. The Lewis

gun was drum-led and aimed with a Norman sight. The

ammunition carried was 400 rounds for the Vickers and

four 97-round magazines for the Lewis. For ground attack

four 25-pound Cooper bombs could be carried in racks

under the fuselage.

In SAAF service, the Foster mounting for the Lewis was

discarded in many cases and the Vickers and bombs were

not fitted frequently.

SOURCES:

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org