The South African

The South African

by Arthur Blake

EDITOR'S NOTE:

This article is the first in a series covering aircraft flown by the South African Air Force. Initially the series will deal with the aircraft on exhibition at this Museum, thereafter an attempt will be made to deal with all military aircraft manufactured in South Africa and later, it is hoped, take in all those that have seen service in the S.A Air Force.

Arthur Blake's interest in aviation and military history goes back to his childhood spent at Stellenbosch. His first book was a history of the Mayors of the town. After completing his schooling at the Hoerskool Jan van Riebeeck in Cape Town, he started his career as a journalist. He has contributed many articles to local and overseas English and Afrikaans magazines, newspapers and encyclopaedias. Others have appeared in Dutch, German and Portuguese publications. During the past 20 years he has done much research work into South African military and civil aviation history. Part of this research appeared in his second book Vlieghelde van Suid-Afrika published some years ago.

During five years spent in Europe he worked at the aero engine works of D. Napier and Sons in London. He has received pilot training. He holds a Commission in the South African Defence Force; has served with the Duke of Edinburgh's Own Rifles (Citizen Force) and is at present a member of the West Park Commando.

Mr. Blake accepted a post as professional officer at the S.A. National War Museum in 1965 but resigned to take up his present post as Chief Sub-Editor with the SABC. His loss was a severe blow to the Museum until he recently accepted the honorary curatorship of the department of aviation since when he has been a tower of strength to the staff and of invaluable assistance to the hundreds of researchers and others seeking information concerning aviation history.

Some experts say the De Havilland DH-9 was a failure. Yet in South Africa it deserves a place among the aircraft which contributed most to the building up of air power. For many years it was the young SAAF's most numerous type and it gave sterling service for nearly two decades after it was discarded as obsolete by the major powers. It was used in a variety of roles from the Air Force's main operational type to crop sprayer, and it carried to safety fortunes in diamonds from remote diggings.

It was designed as an emergency war time stop-gap when in 1917 the British urgently needed a new bomber that would fly higher, faster and with a bigger bomb load than existing types. Captain Geoffrey de Havilland of the Aircraft Manufacturing Co. Ltd. of Hendon, near London, thought he had an answer. He re-engined his popular DH-4 and re-located a petrol tank in the fuselage which separated the pilot and observer/air gunner thus hampering crew co-ordination in action. So emerged the DH-9.

Its close relationship to a type in use facilitated production, and a hard-pressed government ordered hundreds. Then the trouble started; the Puma engine was designed to deliver 300 h.p. but only between 230 and 240 h.p. could be coaxed out of it. In addition the engine suffered from a series of defects which took time to cure. As a result the DH-9 had a poorer performance than the aircraft it was designed to replace, but the production process could not be interrupted and the aircraft went to France. The results were inevitable; unable to climb above 13,000 feet with a war load, casualties followed from enemy action and engine failure. After the war the RAF discarded the DH-9, but the basically similar DH-9A with a Rolls Royce Eagle engine gave good service for many years.

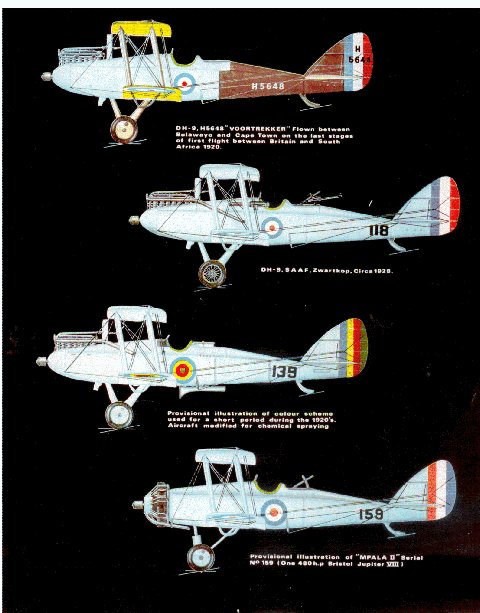

In 1919 the DH-9 was selected as one of the types to be included in the British government's Imperial Gift of aircraft and other equipment to South Africa to form a permanent Air Force. In all, 48 aircraft were shipped to the Union. First to be assembled was H-5648 which was flown to Bulawayo early in 1920 for delivery to Lt.-Col. H. A. ("Pierre") van Ryneveld (later General, Sir ... KBE, CB, DSO, MC) and Squadron Leader Christopher J. Quentin Brand (later Air Vice-Marshal, Sir . . . KBE, DSO, MC, DFC). Their Vickers Vimy had crashed at Bulawayo during the first flight between Britain and South Africa, and H-5648, christened "Voortrekker", was used to complete the historic flight to Cape Town.

The process of establishing and building up the SAAF now began and for many years to come, the DH-9 was to be the workhorse. The strength returns for 1926 are a good indication of the number of DH-9s in use in comparison with other types. Of the 46 aircraft in operation, no less than 25 were DH-9s. The others were: seven DH-4s, three S.E.5As and eleven Avro 504K trainers. Thus more DH-9s were in use that year than all the other types combined.

The SAAF's first operational missions were flown in 1922 during the labour unrest on the Reef. DH-9s were involved, and it is believed that "Voortrekker" crashed during these operations. A few months later DH-9s were sent to South West Africa where the Bondelzwart Hottentot tribe was causing disturbances. Between the end of May and the beginning of July, 105 hours were flown under difficult conditions before order was restored. The SAAF was back in South West Africa in 1925 when a rebellion by the Rehoboth Baster nation was ended in a day. Then followed a month-long tour of the territory as a show of force.

1925 was also the year in which the DH-9 was used to run a regular air mail service in both directions between Durban and Cape Town. Ten or eleven aircraft -- including 101, 106, 110,113,127,136,137, 138 and l39 -- flew the service with 100% regularity between March and June of that year. A Snout Beatle outbreak in Natal in 1925 was fought by at least one DH-9 converted into a crop sprayer.

In 1927 a flight of DH-9s took part in a flight up the Africa Air Route to Kenya for exercises with Imperial forces in the Colony.

From 1928 the DH-9 and later re-engined versions were used to fly parcels of diamonds from the remote State Diggings at the mouth of the Orange River to Cape Town. These flights lasted for up to six hours over a barren region, and a fortune in diamonds was flown safely until the service petered out in the early thirties.

Over the years the DH-9 also performed a variety of other duties. It was used in mapping operations which covered a large area of the Union and neighbouring territories. In the Army Co-operation role it visited peace-time training camps held in various parts of the country and spotted for the artillery during live round practices on the Potchefstroom range in the Transvaal. From time to time there were also exercises with the British Royal Navy units stationed at the Simonstown naval base. The DH-9 was also used to demonstrate the power of the SAAF at Wapenskou demonstrations in the rural areas.

A large part of the SAAF's training programme for Permanent Force and Reserve officers was carried out on the type. Apart from its use in operational training, it also served as an advanced trainer, and as such underwent a metamorphosis. In the first stage the Scarff Ring disappeared from the rear cockpit; then dual controls were installed and the fuselage altered to remove the last traces of where the Scarff Ring had been, and a cut-down cockpit (as in the pilot's position) was installed. During overhauls the aircraft were re-covered and the more drab camouflage schemes used during the war disappeared to make way for the new SAAF overall silver-coloured finish. The British serial numbers also disappeared from about 1923 and a South African block between 101 and 148 was used instead. With the conversion of the aircraft to take more powerful engines, new serial numbers were allotted and the block was extended through the 150's into the 160's.

By 1926 it was realised that the aircraft in service with the SAAF were obsolete, but as lack of funds precluded the purchase of newer types, it was decided to re-engine the basic DH-9/DH-4 air-frame. Engines were the 180 h.p. Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar; the 300 h.p. A.D.C. Nimbus; the 200 h.p. Wolseley Viper; the 450 h.p. Bristol Jupiter VI and the 480 h.p. Bristol Jupiter VIII. The Jaguar-engined version was known as the DH-9J; the Viper-engined version as the Mantis; the Jupiter VI version as the M'pala (or Impala) I and the Jupiter VIII version as the M'pala II. The M'pala I was a single-seater aircraft while the M'pala II had a crew of two. The M'pala models were also further changed to include among other modifications a modified undercarriage.

In spite of many creditable flights by some of the conversions, it was soon realised that new engines in old airframes were not the answer to the problem. In 1929 a licence to build the Westland Wapiti under production in South Africa was acquired. This aircraft was designed as a replacement for the DH-9A in British service and made use of a number of the DH-9 components.

Although being replaced, nearly a decade of service was left to the DH-9 and its re-engined versions. The DH-9J was fitted with an electrically-operated camera for aerial survey work while the M'palas flew to Khartoum in 1929 to exercise with the RAF. They soldiered on during the depression years of the early thirties and the average cost of an hour's flying was about 30 shillings; very economical by today's standards.

The logbooks of many South African pilots who were later to become famous as military or civil pilots reflect many hours spent flying from Zwartkop in the DH-9. Although new types were arriving to take its place, it still formed a large proportion of the aircraft available to the Flying School, the Flying Training School and the Cape Squadron at Zwartkop. By 1935 the end was approaching. In that year the following serial numbers were flying: 106, 115, 118,119, 125 and 131 in addition to some of the converted aircraft.

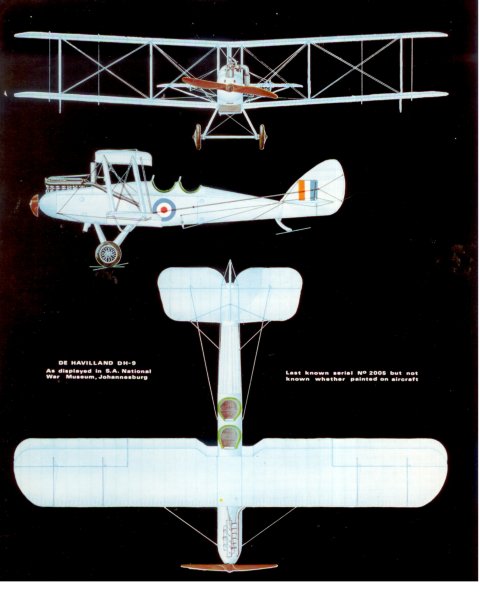

In 1938 the Puma-engined DH-9s still left with the SAAF came under the hammer, and were sold to private owners including charter companies. Between June and August at least five were registered by their new owners as ZS-AOD, AOE, AOG, AOI and AOJ. Three were scrapped before the Second World War broke out -- AOD, AOG and AOJ. The other two were still the property of African Flying Services when the SAAF started impressing aircraft in 1939-1940. They must have been in a poor condition as the SAAF paid only ten pounds each for them. ZS-AOE became 2001 and AOI became 2005 when they were taken on strength. Whether they flew again is not known, but they were used as Instructional Airframes. The fate of 2001 is not known, but 2005 became Instructional Airframe No. 8 (I.S 8) at No.70 Air School, Kimberley. A Board of Survey sat on December 5th, 1942, to survey the aircraft. It was found to be obsolete, 100% damaged, and with no engine. The timber was brittle and unsuitable for training. It was struck off charge on 19 April, 1943, when its value was placed at 5 UK Pounds. A Puma engine was found for it and 2005 was issued to the South African National War Museum. It has since been restored and is in good condition and on display. The history of the re-engined DH-9/DH-4 airframes after 1938 is obscure but the Jaguar-engined version survived until 1943 when it was scrapped at Zwartkop.

CONSTRUCTION:

The fuselage was manufactured of wood, partly covered with doped fabric. The basic spruce and ash structure's forward section, and that below the tailplane, were covered with 3 mm. plywood, producing a strong but light structure requiring no further bracing. Between the cockpit and the tailplane, the structure was a conventional box girder covered with fabric.

The pilot sat in an open cockpit behind the wings. By today's standards there were hardly any instruments on the panel. The gunner/observer sat behind the pilot in an open cockpit fitted with a Scarff Ring. The tailplane control wires ran exposed along much of the rear fuselage.

The mainplanes and tailplane were identical to those of the DH-4. They were of a two-spar layout with the spars spindled for lightness between the ribs. The wing chord was 5 feet 6 inches and the gap between the upper and lower mainplanes was also 5 feet 6 inches. The wing area was 434 square feet. Ailerons were fitted to the bottom and lower mainplanes. The undercarriage was fitted with rubber cord suspension -- two lengths of 6 feet 9 inches wound into nine turns for each wheel.

ENGINE:

One Siddeley Puma developing 230 h.p. at 1,400 r.p.m.

The well-known British aero engine designer H. P. Halford was influenced by the Aluminium Monobloc construction method developed by the Swiss Hispano-Suiza company when he designed the B.H.P. (later Siddeley) Puma in 1916. Basically the engine was a six cylinder, water-cooled vertical type, manufactured mainly from the then relatively little used metal aluminium. This was done to save weight and to increase the critical Power/Weight Ratio. Steel liners were fitted to the cylinder heads. Complete with the airscrew boss, carburettors and twin-magnetos, the Puma weighed 680 pounds. It developed 230 horsepower at 1,400 revolutions. The Power/Weight Ratio was 16.2 lbs. per horsepower.

The fuel tank held 74 gallons of petrol of a comparatively low octane by today's standards. This was consumed at the rate of .55 pints per horsepower hour giving the DH-9 an endurance of 4.5 hours of flight. The Puma was fitted with two Zenith carburettors with altitude control, while the ignition was by dual magneto serving two plugs per cylinder.

The oil tank held 4.5 gallons of oil which was consumed at a rate of .025 pints per h.p. hour. Lubrication was by force feed from a dry sump fitted with suction and pressure pumps. For cooling purposes, 6.5 gallons of water were carried which circulated through a radiator mounted under the engine in the front fuselage. (To control engine temperature this radiator was retractable.)

Other technical details included a bore of 145 mm. and a stroke of 190 mm. The camshaft operated direct on exhaust valves and by overhead rockers to inlet valves.

Initially the aluminium cylinder blocks were defective. Many failed before the casting processes were improved. Exhaust valves also burnt out. Both these problems were overcome to a large extent by the time the engine entered service with the SAAF. Although fairly trustworthy, the Puma was obsolete by world standards during its use in South Africa yet it gave many years of service.

ARMAMENT:

A fixed .303 Vickers machine gun fired through the propeller arc by means of the Constantinesco CC synchronising mechanism. The pilot aimed through a primitive ring-and-bead sight. The observer sat in a Scarff Ring fitted with a .303 Lewis machine gun fitted with a Norman sight. The Lewis gun was modified in comparison with the normal infantry weapon by the removal of the tube covering the barrel.

Various bomb loads could be carried. A bomb bay was fitted between the pilot and the engine where bombs could be housed internally. Normally these consisted of two 230 pounders stowed vertically. Four 112 pounders could be carried under the lower wings. In SAAF service, the 25 pound bomb was usually fitted. A Negative Lens bomb sight was carried.

A wireless could be fitted for Army co-operation duties, and some aircraft were fitted with a hook to pick up messages from the ground.

WHAT WAS IT LIKE TO FLY?

An official Testing Report from Martlesham Heath, dated November, 1917, states: "This machine is fairly suitable for day bombing. Not suitable for night bombing, as lower plane shuts out the most important part of pilot's view. The pilot's view for fighting is better than in the DH-4, and it is a great advantage to have pilot and observer close together. But for all reconnaissance work the pilot's bad view of the ground will be a very serious disadvantage. The manoeuvrability is good. Actual landing very easy, but approach difficult owing to bad view and flat glide. Length of run to unstick, 112 yards; to pull up (engine stopped), 160 yards."

On at least one occasion the DH-9 showed what it could do if attacked by fighters. In August, 1918, a large number of enemy fighters made persistent and repeated attacks on DH-9s of Number 49 Squadron, RAF. An observer of 49 Squadron, 2nd Lieut. E. A. Simpson, shot down 4 of the enemy, 2 of them in flames.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org