The South African

The South African

By Michael Schoeman

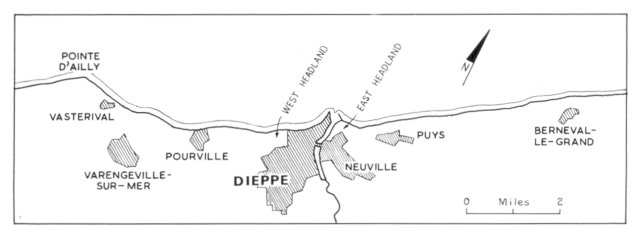

Photographic reconnaissance revealed entrances to the caves in the cliff faces of the two headlands which flanked the Dieppe seafront and overlooked the beaches. Their importance was not difficult to guess. The photographic interpreters pointed out that failure to eliminate the defences of these headlands would jeopardize the whole assault. However, after going over the same possibilities of bombardment as before, it was decided to give the enemy as little warning as possible in the hope that the headlands could be taken and eliminated by forces landed on their flanks - the bombardment forces available were certainly incapable of destroying the defences of the headlands. Therefore, with the element of surprise as the key factor, the preliminary softening up of the beachfront defences facing the main assault was to be short in duration. It was not realised that the four destoyers with a combined fire of eight 4-inch guns and the low-level attack by five squadrons of Hurricanes with bombs and cannon fire would be totally ineffective.

For Fighter Command the raid would be the greatest event since the Battle of Britain. In a year and a half of intensive offensive fighter sweeps, the Command had heen quite unable to draw the Luftwaffe into combat in worthwhile numbers -- and, instead of causing Luftwaffe reserves to be transferred from the Eastern Front, had in fact allowed their own squadrons to be tied up in a useless offensive when there was a crying need for them in both the Middle and Far East. But now, with the assault on, and to hold a port on their very doorstep, the Luftwaffe would have no option but to fight in strength. Here, then, would be Fighter Command's opportunity to fight a conclusive battle of attrition with the Luftwaffe in the West.

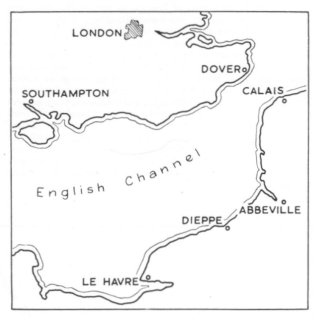

On August 18th the final orders were issued and that evening over a thousand aircrew were briefed under strict security. On the morrow they would support over 6,000 men (mostly Canadians) who were to be landed on the French coast from some 250 vessels. That night aircraft of Coastal and Fighter Commands (including 418 Squadron) flew protective sweeps as the raiding force steamed across the Channel. Meanwhile, as Fighter Command's pilots slept, their opposite numbers in Luftflotte 3 were stood down so as to attend a big dance with the girls of the LN-Helferinnen (Women's Auxiliary Air Signals Corps). At 03.00 on the morning of 19th August, 1942, pilots at the fighter stations of 11 Group dotting South East England were awakened. At 11 Group HQ, Uxbridge, Air Vice-Marshal Leigh-Mallory would be ready to control air operations. His deputy, the famous Air Commodore A. T. "King" Cole RAAF, would be with the Naval and Army force commanders on board the HQ ship, HMS Calpe, to provide liaison with Uxbridge - relaying calls from the beaches for smoke-laying, fighter cover and bombing.

The first attacks were by Commandos against the extreme flank coastal batteries. That against Battery 2/770 at Berneval was only partially successful as only a small party managed to land at 04.45. The RAF provided supporting attacks on the battery with two Bostons and six Hurricane 11Cs (at 05.30). The Commandos kept the battery diverted for almost two hours before withdrawing. The assault on Battery 813 at Varengeville went according to plan. As the first LCAs ground ashore at 04.50, two Spitfires of 129 Squadron shot up the Battery OP near Ailly Light, while others strafed the Battery repeatedly and Hurricanes attacked the two flank batteries behind Vasterival. At 06.26, in close co-ordination with the commandos, Hurricanes delivered the final air attack. By 06.45 Battery 813 was silent. Fw l9OAs then appeared and brushed inconclusively with the Spitfires.

The most important landings were those on the flanks of the headlands -- should the forces landed fail to take them the fate of the whole operation would be sealed. The forces landed at Pourville at 04.52 to take the West Headland were soon bogged down by the German defences. Those landed at Puits to deal with the East Headland (at 05.06 under cover of a Boston-laid smoke-screen), never got off the beach which was subjected to a murderous fire by Battery B/302. An attack by 88 Squadron Bostons at 06.45 had no effect on the Battery. This eventually precluded any evacuation of troops by sea, despite support by 32 Squadron Hurricanes.

At 04.30 the first two wings of the air umbrella, those of Kenley and Northolt, took off. Fifteen minutes later, eight other squadrons were airborne. At 04.50 Sqn.-Ldr. du Vivier led his twelve 43 Squadron Hurricanes in a line abreast low-level cannon strike on the beach defences -- opening the main Dieppe assault. The gunners of the 13th Flak Division, however, caused severe damage to, or loss ot, seven of 43's aircraft. At 05.12 the four bombarding destroyers opened fire on the buildings lining the promenade. While 226 Squadron's Bostons laid smoke-screens, four squadrons of Hurricane 11Cs and 11Bs hedgehopped over the beach, spraying cannon fire and dropping 250-lb. bombs on the German defensive positions with a precision that aroused the admiration of the enemy commander. However, though the cannon fire did keep the defenders' heads down, the few bombs dropped had hardly any effect at all -- and when they were gone the Germans merely re-commenced fire. Heavy and accurate AA fire was encountered, but despite a flak explosion which shattered his jaw, Flt.-Lt. J. F. Scott led his Blenheims on to lay smoke on the East Headland. By 05.15 the air attack was in full swing with Spitfires and 88 Squadron Bostons attacking Batteries 7/302 (behind the West Headland), B/302, and those inland. Then the beach supporting fire and bombing ceased just before the first landing craft touched land at 05.23. The German defences, virtually intact, immediately chopped the main assault force to pieces. On the beaches all control of the situation was lost and with but a few exceptions, the assault was pinned down. However, with the beaches covered in smoke screens and due to a monumental communications break-down, the Force Commanders were to be quite unaware of the real situation for the next three hours, and were to act accordingly till then.

Mist over Jagdgeschwader 26's airfields had precluded immediate action, but JG 2 was clear and the first Luftwaffe sortie, a reconnaisanee to the North West of Dieppe, was off at 05.30. At first only a few German fighters were up, though 71 Squadron shot one of them down as one of the first kills of the day. Between 05.45 and 05.55, the Hornchurch and Biggin Hill Wings became airborne, while elements of their chief adversary, JG 26, joined the fray shortly after 06.00. Before the Hornchurch Wing could intervene, Fw 190s shot down three 174 Squadron Hurricanes (including the CO) which were covering Bostons. The Biggin Wing had a brush with Focke-Wulfs and Lt. Junkin of the 307th Fighter Squadron, 31st Fighter Group, scored the first USAAF kill in the European theatre of operations. At 06.10 the North Weald (Norwegian) Wing began to taxi out. Over Dieppe, Capt. Bjorn Raeder became separated and fought a single-handed action against eight Fw 190s until he disengaged over the Channel and crash-landed in England. Meamvhile, Bostons were bombing the inland Batteries, A/302 and 256. Just behind the latter attack, at Arques-la-Bataille, six Hurricanes went in to attack the 110th Divisional HQ supposedly there. It was not, and four Hurricanes were lost, crashing into the town, killing their pilots and eight civilians. Further main beach landings at 07.05 were only covered by a Hurricane cannon strike on the East Headland, while the smoke-laying aircraft were back at base -- the landing was non-scheduled and the air plan too rigid to allow for adequate immediate cover.

By 07.00 there were only about thirty German fighters in the air and Leigh-Mallory was disappointed. Oblt. Sepp Wurmheller of JG 2, despite a broken leg in plaster, was in action, though he was soon forced to crash on a beach. Later that day, he shot down seven Spitfires and a Blenheim. While Hurricanes searched with MGBs for F-boats in the Channel, 10 (Jabo) JG 26's Fw 190A-4/U8s attacked isolated British ships, though with less success than they claimed. Elements of (F)122 and/or (F)123 also scouted the Channel, looking for another possible British attack force, while the Tactical Reconnaissance Mustangs flew deep into France looking for German reinforcements. Approximately every twenty minutes sections of Hurricanes arrived for ground support patrols over Dieppe, with Bostons at longer intervals. Around 08.30 the first German bomber made its appearance - there now being some fifty Luftwaffe aircraft up.

About 09.00 the Force Commanders became aware of the true situation on the beaches and the withdrawal order, Vanquish, was given for 10.30. However, Air Commodore Cole was forced to point out that the RAF's time table only allowed for a maximum effort to cover Vanquish at 11.00. His point made and accepted, Cole informed Uxbridge at 10.04 that smoke screens would be required over the main beaches for the evacuation from 11.00 for half an hour at least. At 10.10 the final softening up of the indestructible headlands began, and was kept up for 30 minutes by twenty-four Bostons and twenty-two Hurri-bombers: an assault that was too soon and too short.

By 10.00 the German bombers had arrived in force and the Luftwaffe had committed over a hundred aircraft to battle over Dieppe at any one time -- meeting Fighter Command's challenge. With the job of air cover foremost, the RAF was soon paying a high price for maintaining its superlative and near-impregnable air umbrella over the main assault force. It was losing aircraft because its Spitfire VBs (not to mention tactics) were outclassed by the Fw l9OAs and Bf l09Fs, but they were stopping the German bombers from getting at the ships and the beaches. Thus for all its victories, the Luftwaffe was losing the air battle of Dieppe.

At 10.30 twenty-two out of a force of twenty-four B-17E Boeings of the 97th Bomb Group, 8th USAAF, carried out accurate though indecisive bombing of Abbeville-Drucat airfield as a diversion. Ever since 10.00, Luftwaffe fighter reserves between Flushing and Beaumont le Roger had been put on the alert, while bomber forces from Holland to Beauvais were steadily being committed to battle. The Typhoon Wing flew a diversionary feint to Ostend, then over Le Treport they bounced some Fw l90s, damaging three. But two Typhoons failed to pull out of their dives when their tails snapped off. In the end, some nine Spitfire squadrons were sent into the area to stop the bombers reaching Dieppe. The North Weald Wing on their second sortie shot down eight of nine unescorted Do 217Es. Returning over the Channel, a frantic "Look out 190 approaching 3 o'clock!" caused Lt. Kristensen, Yellow One, to whip round and fire a short, effective burst. The 190 burst into flames and dived inverted into the Channel -- it was only then that they realised that it was a Typhoon ... R7815 of 266 Squadron, the pilot being killed.

Back at Dieppe, "Vanquish" was going badly. As 226 Squadron's Bostons laid dense smoke screens on the headlands and along the waterfront at 11.00 to cover the withdrawal, Luftwaffe bomber reinforcements arrived in strength and pressed home their bombardment of the beaches and together with the German gunners turned the evacuation into a worse massacre than Dunkirk. At 11.15 43 Squadron's Hurricanes attacked the East Headland, but five minutes later a call came from the beach for more smoke and air support. Again at 11.35 and 11.38, calls came in to the effect that the beaches were under tremendous fire and evacuation was impossible under such conditions. Uxbridge was inundated with calls for more bombing. Hurri-bombers were on the way, but would only arrive at noon.

At Pourville the remnants of the attack on the West Headland were being evacuated under increasing attack from both shore and air. Fw 1 90s strafed while Ju 88s were subsequently reported as "flame thrower aircraft" (early napalm?). The RAF, however, were fully engaged over Dieppe, and could not give cover here.

At last the Hurricane 11Bs arrived over Dieppe at 12.00, and their attacks kept some German gunners' heads down while Spitfires kept at bay the dogged attempts of Ju 88s, Do 217s and a few He 111s to intervene. At 12.43 three Bostons laid a last smoke screen in the face of heavy AA fire from the Royal Navy. Just after 13.00, however, the survivors on the beaches were forced to surrender -- though, as late as 13.45, RAF attacks were belatedly still going in on the Headlands and beaches, killing several Canadians who were now POWs.

Heading for England now were some 200 vessels in close convoy with the inevitable stragglers behind. With a renewed effort, the Luftwaffe tried to inflict more casualties. For the RAF fighter pilots flying their third, fourth or even fifth sorties of the day, this was the last challenge. Tn addition to the general air cover provided, eighty-six additional patrols were put up to intercept specific attacks. Only one incident was to mar what was otherwise a near-perfect essay into fighter cover. At the tail end of the convoy a free-for-all was developing over the last ships getting into station. At 13.08 a section of three Do 217s, though harried unmercifully by Spitfires, pressed home their attack. Just after 13.14, one bomb exploded under the destroyer HMS Berkeley, breaking her back. Her crew were evacuated and she was sunk by a fellow destroyer. By 15.45, the Luftwaffe, realising the futility of further mass attacks, sent single bombers to harass the convoy, using the gathering overcast for protection. But by 20.00 the convoy was nearly home and the RAF had the sky to itself. During the day the Luftwaffe had made scattered raids on South East England. They came again that night: a Do 217 falling to Wing-Cdr. Pleasance's Beaufighter of 25 Squadron. For several nights afterwards, Ju 88s intensified their shipping reconnaisance over the Channel, some falling foul of 29 Squadron.

The raid had failed, the "Reconnaisance in Force" had succeeded, though the high price was unnecessary. The RAF had played its part to the best of its ability. While it had lost more aircraft than the Luftwaffe in the air battle, the Luftwaffe had been defeated on its own doorstep -- prevented by Fighter Conimand from interfering to any great extent with the assault forces.

However, in other spheres the RAF had not been so successful. Aerial photographic reconnaissance had not been properly utilised nor supplemented by adequate ground intelligence. The tactical reconnaissance had not been completely satisfactory, and, in the fields of bombardment and close-support, the RAF had fallen short -- though through no fault of the aircrew involved: emphasis had always been placed on strategic bombing, while fighter and ground attack development had languished since 1918. In the bombardment, there had been too few aircraft and no heavy bombers -- and too many tasks. 2 Bomber Group's accuracy was also found wanting at that time. The main fault, however, lay with their essentially limited destructive potential. In the role of close support, the fighter-bombers' accuracy was out-weighed by lack of effective ordnance. In general, the situation had been too confused and too poorly co-ordinated for the air attacks to be directed on the most important targets at the right times.

Fortunately, the lessons of the raid had been well learnt, and improved methods of bombardment and support were in evidence in subsequent landings. Most important of all, however, the cross-Channel fighter offensive was duly relaxed. Much needed fighter squadrons were transferred to other theatres of operation, and early in the new year -- with more definite plans for a return to the Continent being formulated -- the Allied air offensive took on new meaning in terms of co-ordination, aims and effectiveness.

It is unfortunate that the important facts regarding the air force's part at Dieppe have since become clouded by the controversy of clashing claims. The Luftwaffe has admitted the loss of 48 aircraft, which Leigh-Mallory never believed, against the total raiding force claim (final) of 91. Luftwaffe fighters claimed 97 and Flak some 15 RAF aircraft against a total of 106* RAF aircraft lost that day. However, all historians to date have lost sight of the fact that only 95 of these, at the utmost, fell to the enemy. At least six RAF aircraft were shot down by the Royal Navy and Army AA gunners. One Typhoon was shot down by a Spitfire, two others were lost due to structural failure, and two Spitfires collided during the withdrawal across the Channel.

It would not be worth quoting a statistical breakdown of the almost 3,000 sorties flown, losses, etc., as, without a chapter on their own, these might only be misconstrued. For example, the two Norwegian squadrons claimed 15 confirmed victories, while the five Polish squadrons between them only got 17 kills. The dictum of being in the right place at the right time applies here.

ALLIED:

Fighter cover - 48 (of which 39 are identified below)

squadrons of Spitfires, two of Typhoons.

| SQDN. | AIRCRAFT | OC | BASE | ORGANIZATION |

| 64 | Spit IX | S/L W. G. G. Duncan-Smith | H | H Wing |

| 65 | Spit V | S/L D.A.P.McMullen | L | |

| 66 | Spit V | T | T Wing | |

| 71E | Spit V | S/L C. Peterson | D | D Wing |

| 81 | Spit V | S/L R. Berry | ||

| 111 | Spit V | S/L P. R. Wickham | ||

| 118 | Spit V | |||

| 121E | Spit V | H. Kennard | D | D Wing |

| 122 | Spit V | J. R. C. Killian | H | H Wing |

| 124 | Spit HF VI | |||

| 129 | Spit V | S/L R. H. Thomas | Thorney Island | Tangmere Sector |

| 131 | Spit V | T | T Wing | |

| 133E | Spit IX | L | BH Wing | |

| 133E | Spit IX | L | BH Wing | |

| 154 | Spit V | S/L D. C. Carlson | ||

| 165 | Spit V | H. J. L. Hallowes | T | T Wing |

| 222 | Spit V | S/L S/L B. Oxpring | BH | BH Wing |

| 266 | Typhoon lB | WM | WM Wing (Duxford) | |

| 302P | Spit V | N | N Wing | |

| 303P | Spit V | S/L J. E. L. Zumbach | N | N Wing |

| 306P | Spit V | N | N Wing | |

| 308P | Spit V | N | N Wing | |

| 310C | Spit V | |||

| 312C | Spit V | |||

| 317P | Spit V | S/L S. Skalski | N | N Wing |

| 331N | Spit IX | S/L H. Maehre | NW | NW Wing |

| 332N | Spit V | S/L W. Mohr | NW | NW Wing |

| 340F | Spit V | S/L B. Duperier | H | H Wing |

| 350B | Spit V | S/L Guillaume | Redhill | |

| 4OlRCAF | Spit IX | L | BH Wing | |

| 4O3RCAF | Spit V | S/L L. S. Ford | ||

| 411RCAF | Spit V | WM | WM Wing | |

| 412RCAF | Spit V | |||

| 416RCAF | Spit V | S/L L. Chadburn | Hawkinge | |

| 485RNZAF | Spit V | WM | WM Wing | |

| 602 | Spit V | S/L P. Brothers | BH | BH Wing |

| 609 | Typhoon lB | WM | WM Wing (Duxford) | |

| 610 | Spit V | S/L E. Johnson | WM | WM Wing |

| 611 | Spit V | S/L D. H. Watkins | ||

| 616 | Spit HF VI | BH | BH Wing | |

| USAAF 307th | Spit V | BH | BH Wing (31st FG) | |

| USAAF 308th | Spit V | Kenley | Kenley Wing (31st FG) | |

| USAAF 309th | Spit V | Westhampnett | T Wing (31st FG) |

| E - Eagle | N - Norwegian | H - Hornchurch |

| T - Tangmere | P - Polish | B - Belgian |

| L - Lympne | D - Debden | C - Czech |

| F - French | BH - Biggin Hill | WM - West Malling |

| NW - North Weald | N - Northolt |

| SQDN. | AIRCRAFT | OC | BASE |

| 1 | Hurricane IIC | Tangmere | |

| 32 | Hurricane IIC | S/L E. R. Thorn | |

| 43 | Hurricane IIC | S/L D. A. R. G. Le Roy du Vivier | Tangmere |

| 174 | Hurricane IIC | S/L Fayollet | |

| 4O2RCAF | Hurricane IIB |

| SQDN. | AIRCRAFT | OC | BASE | [Losses] |

| 2 | Mustang I | (3 a/c lost) | ||

| 26 | Mustang I | Gatwick | (5 a/c lost) | |

| 4OORCAF | Mustang I | W/C R. C. A. Waddell | (2 a/c lost) | |

| 4l4RCAF | Mustang I | W/C R. F. Begg |

| SQDN. | AIRCRAFT | BASE | GROUP |

| 13 | Blenheim IV | Odiham | |

| 226 | Boston III | Thruxton | 2(B) |

| 614 | Blenheim IV | Odiham |

| SQDN. | AIRCRAFT | BASE | GROUP |

| 88 | Boston III | Ford (Tang Sect) | 2(B) |

| 107 | Boston III | Ford | 2(B) |

Heavy bomber diversion - 24 x B-17E-BO 97th Bomb Group,

US 8th AAF, Grafton Underwood.

Air/Sea Rescue - sea: several HSLs.

- air: units of Defiants, Lysanders and Walrus.

11 Group Fighter Command air observation:

one Spitfire (G/C H.Broadhurst).

LUFTWAFFE:

Luftflotte 3 (HQ: Paris).

Jafu 2 (Oberst J. Huth) -

JG 26 (Schlageter) Maj. G. Schopfel;

three Gruppen of three staffels each,

plus two autonomous:

10 (Jabo-Rei)/ and 11 (Hohen)/.

Jafu 3 (Oberst M. Ibel).

JG 2 (Richthofen), Hptm. W. Oesau:

presumed 9 staffeln, plus one Jabo-Rei.

Bomber units

It is possible that elements of the following units took part:

II/KG 1, I/KG 28, II/KG 54, I/KG 77, various/KG 40, Kampfgruppe 100.

A lesser possibility are KGs 2, 4 and 6.

Radar Control -

Covering the Les Petites-Dalles/Dieppe/St.-Valery-sur-Somme area:

23rd Schwere-Funkmess Kompanie under Oblt. Weber.

Flugmeldezentrale, Dieppe: Freya 28 type radar.

Reconnaissance

Elements of Fern-Aufklarer Geschwaders (F) 122 and 123.

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Mr. Walter Nielsen

who made available certain information to him.

FOOTNOTE:

*88 fighters, 10 Mustangs, 8 Bostons and Blenheims.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org