The South African

The South African

(With the exception of Russia, all the belligerents in World War II were signatories to the Geneva Convention of 1929 relative to the treatment of Prisoners of War. This elaborate and lengthy code provides for almost every contingency that might face the prisoner, and its dominant note is that in all circumstances treatment shall be humane. It is not generally known, for example, that the Convention lays down that the food ration of prisoners shall be the equivalent in quantity and quality of that of depot troops. Another article states that medical attention of every kind shall be given a prisoner, when necessary. It is now common knowledge that the treatment meted out to Allied prisoners both in Europe and the East bore very little resemblance to that laid down by the Convention. In South Africa, on the other hand, where for some years we held nca4y 100,000 Italian prisoners, the Articles of the Geneva Convention were most strictly observed, both in the letter and the spirit. Well fed, well housed, well clothed and given the best of medical care, these prisoners were maintained in an excellent state of health. In fact, the general sick rate throughout their period of captivity was consistently lower than that among U.D.F. troops in the Union. The writer of this article, a doctor now back in general practice, was intimately associated with the medical care of the prisoners from the outset until his release from the Forces in 1946. He gives some astonishing facts and figures. The Union can be proud of her wise and humanitarian trusteeship. A hundred thousand captive enemies came to our shores. The majority returned home to Italy firm friends of South Africa.

This article was published in "Health and Medicine" in August, 1946, with the permission of the D.G.M.S. of that time, and is reproduced here with acknowledgements to that Journal.)

In April, 1941, the first foreign prisoners-of-war ever to set foot on South African soil landed at Durban. They were Italians, captured in Libya and Abyssinia. This contingent turned out to be merely the fore-runner of tens of thousands more.

South Africa had never previously been in the position of having to accommodate prisoners of war. During the First World War, our country was too far removed from the actual conflict area, making it impracticable to consider sending them here. Besides which, the number of prisoners taken in those days was never too large to be disposed of in the countries in which they were captured. Nor was there quite the same shortage of shipping and all vital commodities that we experienced once this war had got well into its stride.

The prisoners taken in Abyssinia and North Africa could not be transported to England on account of the danger to our shipping in the Mediterranean. Nor could they be kept, in any great numbers, at the bases in Egypt, which were threatened by the enemy at that time. For these and other reasons the High Command of Great Britain and the Union decided to construct camps in South Africa to accommodate the embarrassing stream of prisoners who began to pour in in an ever-increasing magnitude.

There was also not the food shortage here that was already beginning to be felt in Europe; and on account of the submarine menace the safest sea-route was down the East coast of Africa. But perhaps an even more weighty argument was the fact that with our own Forces going North in ever-increasing numbers, there were ample camp-sites to house the Italians in the Union. This was extremely important. The prisoners began to arrive in their thousands within a very short period of time, and owing to difficulties of sea-transport and the secrecy of movements, little notice was received of the arrival of new batches. Hence these ready-made camp sites were invaluable, making it possible to give the new arrivals a reasonable amount of shelter.

Otherwise there would undoubtedly have been chaos because it was only after the prisoners had already arrived that these temporary camps could be enlarged and completed. But before long, thanks to the administrative efficiency of those in charge, the Prisoner-of-War Camp in Sonderwater became one of the best functioning military camps in South Africa.

In the course of time, as the tide of war turned against the Germans in North Africa, German prisoners were also shipped to South Africa, but they only remained here for a comparatively short time, en route for their final destination in Canada. Everyone was glad to see them go; unlike the tractable Italians, they were truculent, insubordinate and unco-operative towards their guards. There was also a small number of Vichy French prisoners, as well as a couple of thousand Indo-Chinese, captured on the high seas.

With no previous experience to assist them and little to aid them beyond the text of the Geneva Convention, the P.O.W. General Headquarters and Administration in S.A. had every reason to be satisfied with its achievements.

It was generally stated, amongst the Italian prisoners in the Union, that the treatment meted out to them here was better than in any other camps they had occupied elsewhere. The Geneva Convention was adhered to, not only to the letter, but in spirit. The representatives of the international Red Cross Society, as well as those of the protecting power, Switzerland, visited the camps frequently, and were completely satisfied with all they saw. Especially (as they later on had sufficient reason to believe in common with our own authorities) in view of the fact that the treatment meted out to South African prisoners was, in many instances, very far below that required by the statutes of the Geneva Convention.

A general description of the main P.O.W. camp at Sonderwater will give the reader some idea of what it consisted. In the vicinity of the Cullinan diamond mine the Government declared a large tract of land to be a prohibited area, that is, an area which no unauthorised person is permitted to enter. In this prohibited area the P.O.W. camp was situated. The camp was capable of holding 120,000 prisoners (though the largest number at one time was 90,000) and was divided into blocks -- fourteen in all. Each block, designed to accommodate 8,000 men, was further subdivided into four camps, each of approximately 2,000 men.

These blocks were not adjacent. Each separate one was surrounded by two high barbed wire fences, on which sentries were posted on raised platforms, overlooking the whole block, at short distances from one another. All night these perimeter fences were lit by strong arc lights, which made a very impressive picture from afar.

Each block was a self-contained unit, with its own administrative officer and staQ its own medical inspection room, store-room, sports field and theatre; while every camp within the block had its own separate kitchen and ablution facilities. The inmates of each block developed a solidarity -- a kind of local patriotism to their own piece of earth, and there was great rivalry between them. They planted gardens round their huts, and erected statues and fountains in the grounds. It was not long before this section of the High Veld began to take on the character of an Italian village.

HYGIENE

It is a well-known fact that the incidence of disease is in direct proportion to the hygiene conditions of a camp, and

as the general health of the prisoners was astoundingly good, it follows that the hygiene must have been excellent. This

was due to the following factors:

(1) Scrupulous cleanliness in the kitchens, latrines, barbershops, showers and the housing quarters.

(2) The establishment of two disinfesting stations, each capable of de-lousing 1,000 prisoners and their belongings

daily. No new arrival was permitted to enter the blocks until he had been disinfested, and no man was transferred

or sent on outside employment before going through this process again.

(3) Vaccination and re-vaccination against smallpox.

(4) Inoculation and re-inoculation against typhoid.

(5) Daily food inspection by qualified food inspectors.

(6) Purification of all drinking water.

(7) Regular road watering and the construction of storm-water drains.

(8) Establishment of modern sewage-disposal works.

DIET

The resistance of the prisoners to disease was greatly strengthened by a liberal and carefully balanced diet. This amounted to approximately 3,000 calories per day.

Dietetic Rations for the Hospital

These were based on rations supplied to U.D.F. Hospitals

as follows: Ordinary Diets, Fish Diets, Milk Diets.

(According to the official Red Cross statistics, supplied from Geneva, South African prisoners of war in Germany

were receiving hardly 2,000 calories a day, while in Italy they were given just over 1,000. In contrast, the Italians

were able to supplement their daily 3,000 calories at the richly-stocked canteens in all the blocks, where they were

allowed to buy additional food with their monthly pay.)

| Daily Ration | oz. |

| Bread | 12 |

| Meal | 2 |

| Mealie bread | 1.5 |

| Fresh meat | 5 |

| Potatoes | 10 |

| Fresh vegetables | 6 |

| Dried beans, peas or lentils | 2 |

| Onions | 2 |

| Macaroni (weekly) | 4 |

| Jam (weekly) | 5 |

| Fresh fruit (twice weekly) | 16 |

| Dried fruit (weekly) | 2 |

| Sugar, Government grade (weekly) | 8 |

| Salt | 0.375 |

| Coffee | .33 |

| Cooking fat | .75 |

| Cheese (weekly) | 2 |

| Vitaminised peanut butter (weekly) | 4 |

| Fresh milk - pints - | 0.375 |

Where these articles were unobtainable or in short supply they were given equivalents in the form of biscuits, oatmeal, preserved meat, sweet potatoes, mealie rice, condensed milk, etc.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

The medical care of prisoners of war commenced immediately on arrival in this country. This was considered very important, as it was feared that diseases such as malaria, dysentery and infectious diseases might be introduced into South Africa, and as the main camp was situated at Sonderwater, adjoining our own troops, cross-infection had to be prevented at all costs. A special medical section, dealing only with prisoners of war, was established, and it functioned extremely well. In fact, it earned the distinction (as expressed by the War Office) of having the best P.O.W. Hospital in the British Empire.

Not only were there no epidemics at any time in the camp, but the statistics showed most satisfactory figures relating to the state of health, the preservation of health, and the low incidence of infectious diseases.

Of course many other factors, besides medical care, come into play to account for the gratifying state of health of the prisoners throughout their captivity. The following facts must be taken into consideration:

The majority of the prisoners were peasants, of sturdy stock.

They were unable to get alcohol in any large quantities.

Their cigarette and tobacco ration was very small.

The possibility of contracting any venereal disease was practically non-existent.

They were not exposed to the danger of vehicular, training or other accidents.

Their average age was 25 years.

They were not exposed to the inclemency of the weather, and they had more than ample time for repose.

Their food was excellent and well-balanced.

MEDICAL ORGANISATION

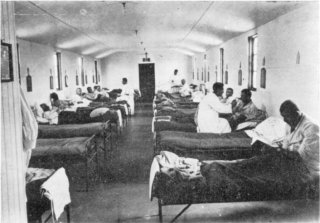

The actual medical organisation of the camp was run on the usual military lines. There were ordinary medical inspection rooms, two in each block, where medical cases were seen daily, but cases requiring hospitalisation and special investigation were sent to the P.O.W. Hospital. This hospital, which was situated on the outskirts of the camp, but within the prohibited area, was the largest military hospital in the Union. It contained approximately 3,000 beds, and was spread over a very large area, the distance from the entrance gate to the last ward being a mile. The buildings consisted of a complex of bungalows, each containing 18 to 20 beds.

It possessed all the special departments of a modern hospital. There were up-to-date operating theatres, X-ray department, ear, nose and throat section, an ophthalmic and a gastro-enterological department. There were also pathological, bacteriological and dental departments, while special buildings were set apart for tubercular, venereal, skin and mental cases. As the number of mental cases increased, however, it was found impossible to cope with them satisfactorily in a general hospital, and they were ultimately transferred to Krugersdorp Mental Hospital, which formed, as it were, a distant annexe of the main P.O.W. Hospital.

The hospital was staffed by Italian protected personnel, and administered by a U.D.F. staff consisting of the A.D.M.S., P.O.W., three medical officers and about 50 S.A.M.C. non-commissioned officers. The patients were treated by their own ltalian physicians and surgeons (of whom at one stage there were roughly 160) and nursed by Italian medical orderlies. But cases which required very special treatments that could not be carried out in the hospital, were transferred to our own Military Hospitals in Pretoria and Johannesburg.

To give you some idea of the work done in the P.O.W. Hospital, here are a few statistics from the year 1942/1943:

| Total visits to Medical Inspection Rooms | 467,252 |

| Admissions to Hospital | 11,174 |

| Attendances at: Ear, Nose and Throat Department | 13,277 |

| Attendances at: Eye Department | 10,816 |

| Attendances at: Dental Department | 6,949 |

| Dentures made | 114 |

| X-ray Department: Total cases examined | 5,269 |

| X-ray Department: Screenings | 3,706 |

| X-ray Department: Films used | 2,688 |

| Physio-therapy Department: Total applications | 9,984 |

| Deaths | 56 |

| Tuberculosis, pulmonary | 219 |

| Tuberculosis, other | 18 |

| Typhoid | 2 |

| Scarlet Fever | 2 |

| Paratyphoid | 1 |

| Chickenpox | 3 |

| Malaria | 151 |

| Amoebiasis | 306 |

| Syphilis | 5 |

| Gonorrhoea | 13 |

| Bacillary Dysentery | 1 |

| Diphtheria | 1 |

| oz. | |

| Bread | 4 |

| Meat | 3 |

| Sugar | 1 |

| Potatoes | 4 |

| Dried peas, beans | 1 |

| Oranges | 1 |

| Fruit or vegetables | 2 |

WELFARE

Hysteria is a common occurrence in all prisons and prison camps, and as the Italians are an emotional people, the incidence of hysteria amongst them was relatively high. The manifestations ranged from hysterical blindness and aphonia (loss of speech) to complete paralysis. In order to combat this hysteria and depression amongst the P.O.W. the Welfare Section of the camp, in close co-operation with the medical side, started a number of measures to keep the men's minds occupied and to awaken their interest in matters other than their own captivity.

Schools were started in all the blocks, and there were classes in foreign languages, history, science and literature for the more educated men, while for those who were entirely illiterate -- and there were many -- there was regular elementary school. Arts and crafts workshops were opened and excellent work was done. Once a year an Exhibition and Sale of Work was held which was open to the general public, and there was much competition amongst the visitors to acquire the various objets d'art.

Encouraged by the Welfare Officers, theatres and orchestras sprang up everywhere in the camp. At first the musicians were unable to obtain instruments, and the ingenuity with which they manufactured them was unbelievable. Violins were made from purloined lavatory seats, and drums improvised from all conceivable odds and ends. Later they were able to buy instruments from the profits of the various canteens, and then, from morning to night the air rang with operas, concertos and nostalgic Italian folk-songs.

But the prisoners' most notable achievements were undoubtedly their theatre performances. Their repertoire ranged from classic dramas such as "Cyrano de Bergerac" to modern drawing room comedies, light opera and reviews. Their costumes were made from anything they could beg, borrow or steal. I have seen women in the audience gasp with envy at a superb ermine coat, which turned out to be entirely of cotton wool (as we discovered later on checking the medical stores). The men's clothes, made of dyed sacking, were the last word in cut and elegance. Occasionally, a beauty chorus of hairy, muscular, blue-chinned sailors in diaphanous ballet dresses convulsed the audience. Some of the "leading ladies" were so convincing and charming that it was difficult to keep some of the visitors away from the stage door.

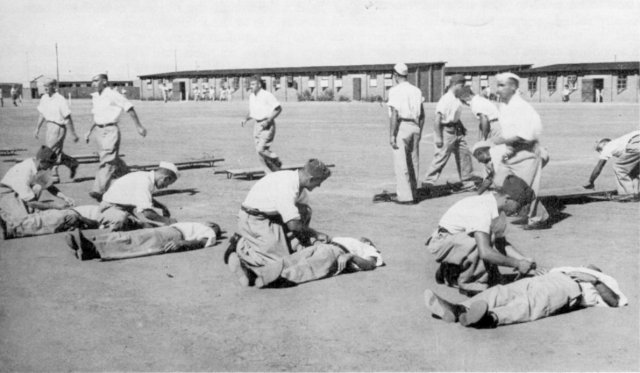

There were also facilities for most outdoor sports. The most popular game was soccer, and there were a number of internationals among the players. Inter-block matches were played right through the season. There was keen competition for the trophies presented by the Welfare Section. The prisoners also played tennis, handball and bowls, and there were some first-class boxers and fencers amongst them.

In short, everything possible was done to keep the prisoners healthy in mind and body. After six years in captivity -- in a foreign land, away from all they held dear -- these men returned to their country in no way degenerated. On the contrary, they were useful and profitable years for most of the prisoners.

Addendum: The following article was sent to the website editor by its author and is placed here because of the Italian connection. There is also a Zonderwater ex-POW Association which helps trace prisoners' records and descendants: contact Emilio Coccia on +27-(0)12-667-3279 (Fax or phone) as he does not have e-mail.

Introduction

It is not commonly known that the Italians were involved with the construction of the Voortrekker Monument. Apart from the fact that the initial construction, till after the placing of the corner stone (1938) was done by an Italian firm, Italians were also involved with the construction of the laager wall and the casting of the Anton van Wouw statue of the woman and children in front of the Monument. Further more the marble frieze was chiselled from Italian marble in Italy.

During the 17th and 18th century a small number of Italians settled in South Africa, but it was only in 1880 during the gold rush, that their numbers increased appreciably. By 1890 for example, there were between 150 and 200 Italians in the Cape Colony and towards the end of that decade about 1200 in the Transvaal.(1) Many of them were miners, builders and businessmen.(2) However, not all of the Italians were workmen and shop owners - there were also professionals among them such as doctors, lawyers, engineers and also artists. There were between 3 000 and 4 000 Italians in South Africa by 1900.(3)

When South Africa became a Union in 1910 the building industry blossomed. Two new capital cities, Cape Town and Pretoria, had to be provided with public buildings. For example a great many stonemasons, bricklayers and decorators worked on the construction of the Union Buildings in Pretoria (1910-1912) - many of them were Italian.(4) There was discernible prosperity in the 1930's with the development of the industrial, commercial and agricultural activities in the Italian community. On the forefront were the families Carleo (mechanical industry), Lupini (building material), Gallo (railroad construction) and Rossi, Beretta and Lombardi (farmers). Italian industrialists, businessmen and individual technicians contributed to the country's prosperity.(5)

Background: The Central People's Monuments Committee (Die Sentrale Volksmonumente Komitee)

At the Congress of the Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Societies (Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge) in 1931 representatives from several monument committees and other interested organisations under the chairmanship of doctor E.G. Jansen met in Bloemfontein. The aim was to establish a central body for the construction and maintenance of people's monuments. The Central People's Monuments Committee (SVK) was established and they decided to erect a national monument in honour of the Voortrekkers during the 1938 centenary celebrations.(6)

After thorough deliberation it was eventually decided to erect the monument in Pretoria and the SVK assigned the architect Gerard Moerdyk to design it. The design was approved in 1936 and tenders were submitted for the construction.(7)

Construction

The groundbreaking ceremony took place on Monument Hill on 13 July 1937. Advocate E.G. Jansen, chairman of the SVK, turned the first sod.(8) Progress with the excavations and foundation was already well on the way by February 1938 and tenders for the construction was obtained. (7,646 cubic metres of concrete were eventually used in the foundation of the Monument).(9) Ten tenders were obtained and the lowest tender (£175,000) was accepted, namely that of the Italian construction firm, A. Cosani. The construction started early in 1938(10) and the cornerstone of the Voortrekker Monument was laid on 16 December 1938 as the highlight of the Central Centenary celebrations in Pretoria.

After the onset of the Second World War in 1939 construction came to a standstill whereupon Cosani wanted to be discharged from the contract because he was not strong enough financially to complete the construction. Most of his security was in Italy where he also had to obtain a lot of the machinery and tools. The contract was concluded in good spirit and the SVK paid Cosani an amount of £2,103 for the work already completed.(11)

The tender for the completion of the construction was accepted from the firm W.F. du Plessis in Bloemfontein in 1940 - the firm would make use of white builders exclusively. As a result of the war there was an increase in the loss of white workers and from 12 black workers were used to mix the concrete and clean the site from 1942.(12)

Statue: Woman and children

At the base of the Monument there is a statue of a Voortrekker woman and her two children. Moerdyk gave pride of place to the Voortrekker woman, because without her contribution the Great Trek would not have lead to lasting settlement.

The sculptor was Anton van Wouw (1862 - 1945). This sculpture group was his last commission as he was already nearly 76 years old. He used a nurse, Isabel Snyman, as a model for the Voortrekker woman and Betty Wolk and Joseph Goldstein as models for the children. Apparently Van Wouw started early in July 1937(13) with the sculpture and his contract with the SVK ended on 31 March 1938.(14) The Woman and children is 4.1 metres high, weighs 2,5 tonnes and was cast by the firm R Vignali in Pretoria.(15)

What makes this bronze sculpture group unique is that it is the first public sculpture that was cast in one piece in bronze in South Africa. Renzo Vignali quoted Van Wouw £725 for the casting: The casting of the bronze in one piece will give a better result as there will be no weldings or alteration whatsoever. The alloy of the metal to be used shall be of 84% copper, 14% tin, 2% zinc...(16) (The Woman and children was removed from the base of the Voortrekker Monument in 1965 by the same firm in Pretoria and cleaned - the first time that it was done).(17) Renzo Vignali (1903 - 1945) came to South Africa from Italy in 1931, apparently on Van Wouw's insistence.(18) He was a practised bronze caster mastering the art in his father's foundry in Florence. He stayed in Johannesburg initially but later moved to Pretoria West where the sculpture group of the Voortrekker woman and children was cast in bronze on 5 August 1939.(19) For this task Renzo Vignali called for the help of his father, Gusmano Vignali (1867 - 1953). Gusmano arrived in South Africa early in 1939 and also helped his son to cast the Coert Steyberg statue of Louis Botha in front of the Union Buildings.(20) The Vignali foundry moved to Pretoria North in 1942 where it is still in business.(21)

The Vignali Foundry played an important role in the art history of South Africa - during the first 27 years of its existence (1931-1958) it was the only foundry in South Africa specializing in the casting of works of art.(22) Before Vignali's arrival in South Africa artists, (amongst others van Wouw), had to have their works cast overseas - in countries such as Italy and the Netherlands.(23) This brought about high costs and delays. Hendrik Joubert, an employee of the Vignali foundry, started his own business in 1958 and since then several independent foundries have seen the light. The pioneering work in this regard was however done by the Vignali Foundry.(24)

Renzo Vignali unexpectedly died in 1945, leaving his wife Vittoria and daughter Gabriela behind. His father, Gusmano, extended his stay in South Africa with two years to finish Renzo's uncompleted works. Thereafter, Luigi Gamberini (1916 - 1987) an employee of Vignali and a former Italian prisoner of war from Zonderwater, continued the business. Luigi Gamberini married Renzo daughter Gabriella in 1960.(25) After Luigi Gamberini's death his two sons, Lorenzo and Carlo Gamberini took over the Vignali Foundry, supported by their mother, Gabriella. She died in 1996. Although the two Gamberini brothers were born and bred in South Africa they learned the art of casting in the Italian manner and they still respect the old proven casting techniques.(26)

The Vignali Foundry also cast Phil Minnaar's statue of general P.J. Joubert (1971). This bronze bust is currently standing at Fort Schanskop that is part of the Voortrekker Monument Heritage Site.(27)

Historical frieze

The frieze against the walls of the Monument's Hall of Heroes is an intrinsic part of its design - the story of the Great Trek from 1835 to 1852 is depicted relief on 27 panels. The frieze does not only depict the Great Trek, but also a way of life, methods of labour, conflict, religious beliefs and the way of life of the Trekkers.(28) The frieze cost £30,000 to create, is 92 metres long and one of the biggest marble friezes in the world.(29)

Four sculptors created the frieze, namely Hennie Potgieter, Laurika Postma, Frikkie Kruger and Peter Kirchhoff. They worked for five years creating the plaster of paris panels whereupon it was sent to Italy to be chiselled from marble. According to Hennie Potgieter it was decided to chisel the panels in Italy as the South African marble was not suitable for sculptures of that nature. It would have been cheaper to transport ready-made panels of marble from Italy instead of importing the heavy blocks of marble and finishing the sculptures on site.(30)

Fifty initial chisellers under the supervision of the well-known Italian sculptor professor Romano Romanelli (1882 - 1968) started the panels. Initial chisellers are not artists but with the help of a dotting machine they are able to chisel and reproduce the work of a sculptor precisely. Romanelli had a large studio with machinery and technical apparatus in Florence where initial chisellers could work together. Romanelli was interested in the South African history and made a thorough study of the Great Trek.(31) Hennie Potgieter and Laurika Postma stayed in Italy for a year to ensure that everything went according to plan (1947 - 1948).(32)

Three hundred and sixty metric tonnes of Quercetta marble was taken from the quarries - the finished frieze weighs about 180 metric ton.(33) There were constant strikes in the marble quarries in Italy and therefore the work was delayed. Two months before the inauguration of the Monument a few of the panels were only arrived in Durban and they still had to be transported to Pretoria.(34) Eight panels of the frieze were not ready when the Monument was inaugurated.(35)

With the inauguration of the Monument a medal was sent to Romanelli to honour him for his involvement. After seeing photos and plans of the monument, he declared that it was a very important monument from an artistic viewpoint, a first rate creation.(36)

Thérèsa Viglione

Panel 15 of the marble frieze is a depiction of the heroic deed of the Italian woman Thérèsa Viglione. She was a trader who camped near the Trekkers with 3 Italian men and three wagons to trade. During the attack by the Zulus on Bloukrans on 17 February 1838, she fearlessly charged down the banks of the Boesmans River on a horse to warn the laager of Gerrit Maritz against the oncoming Zulus. Because of her action the Trekkers were forewarned and could defend themselves - many lives were saved.(37) After the attack she nursed the wounded children in her tent and thereby also drew the respect of the Trekkers.(38) Frikkie Kruger, the sculptor of this panel, used an Italian woman, Lea Spanno, as the model for Thérèsa Viglione.(39) Lea Spanno worked in a chemist in Sunnyside near the artist's studio.(40)

Laager Wall

Around the Monument is a laager wall of 64 wagons - the same amount of wagons as at the battle of Blood River (16 December 1838). The Voortrekkers drew a laager with their wagons when danger was threatening and have proven its military worth. The laager wall forms a symbolic rampart against everything clashing with the ideals and views of the Voortrekkers.

The laager wall consists of terrazzo work - a mixture of pieces of marble and cement. White cement was imported from America and pieces of white marble from the quarries at Marble Hall were used as well as pieces of blue granite from Namakwaland.(41) The Dey firm in Pretoria laid the foundation of the laager wall in March 1949. Frikkie Kruger made a clay model of the wall whereupon a plaster of paris imprint was taken to Johannesburg. Imprints were made in cement and the Italian firm Lupini in Johannesburg cast the final sections. The final cement sections were transported directly to the Monument where the final casting took place.(42)

The first wagon was finished in March 1949. Every wagon weighs about 8 tonnes43 and is 4,6 metres long, 2,7 metres high and compiled from 24 sections.(44) The total length of the laager wall is 313 metres. Nearly all the artists who worked on the wall were Italian.(45) A photograph of two of the Italians, namely Fornoni and Carrara appears in the Transvaler of 21 April 1949.(46)

Summary

From the above it is clear that up to now the Italians who had a stake in the history of the Voortrekker Monument have not had the acknowledgement that they deserve. They are sometimes only mentioned in passing in literature on the subject and this has made research very difficult.

The grandson of Romano Romanelli, Laurent Romanelli, sent photographs of his grandfather to the Voortrekker Monument on 22 May 1995:

Estelle Pretorius

Researcher,

Voortrekker Monument

Pretoria

research@voortrekkermon.org.za

References:

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org