The South African

The South African

by Squadron Leader D.P. Tidy

The first two articles in the series "South African Air Aces of the 1939-45 War" appeared in Volume 1, No.3 of this Journal.

Sincere thanks are extended to the Imperial War Museum, London for the picture of Sqn. Ldr. J. J. le Roux and to Mr. E. C. R. Baker, author of "The Fighter Aces of the RA F". for that of Gp. Capt. P. H. Hugo.

Squadron Leader J.J. le Roux, DFC and two Bars Johannes Jacobus le Roux joined No. 73 Squadron, Royal Air Force as a twenty-year old in 1940, when that squadron was part of the Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF in France during that strange period of World War II known to the French as "la drole de guerre". It was a war of singularly little major action up to May, 1940, and the Americans called it the "phoney war", but the epithet was hardly justified. One of the contestants, Britain, was saving and building up her strength for the later stages; Germany, the other, was about to launch an all-out attack which was to culminate in the evacuation on from Dunkirk of the British and French forces. It was to this odd war that No.73 Squadron flew their Hurricanes in 1939, and which young Chris le Roux entered when he joined the squadron in 1940.

When the Luftwaffe opened the assault in May, the AASF and the RAF Component (with which Dutch Hugo, the subject of our next profile, was flying) escaped lightly. Soon, however, Chris (as he had been known throughout his service in the RAF) le Roux was in the thick of the fighting, for the AASF fighters had to cover the evacuation of the ground staff, and the three remaining Bnitish divisions. For the defence of Nantes and St. Nazaire there were but three squadrons, Nos.1, 73 and 242) all equipped with Hurricanes; yet in spite of this sparse air cover the evacuation of the troops was entirely successful. The Luftwaffe dropped bombs by day and mines by night but achieved remarkably little. Denis Richards relates in "The Fight at Odds" (HMSO) that only off St. Nazaire, where German bombers sank the Lancastria with 5,000 troops aboard, was there a major disaster. In this case the enemy made clever use of cloud cover to elude the patrolling Hurricanes.

By the afternoon of 18th June, 1940, the ground forces had made good their escape, and the fighters, most of which had flown six sorties on the previous day, were free to depart. After No. 73 Squadron had flown the final patrol, the last Hurricanes left Nantes for Tangmere and the mechanics set fire to the unserviceable machines.

I can find no details of Chris le Roux's combats in France, and would be most grateful if any of our readers can tell me if his Log Book survived, and if so, where it is now, or if any of his relatives survive and can help with details of his life, for he is one of the least-known aces of the war. E. C. R. Baker in "Fighter Aces of the RAF" ( William Kimber states that Chris was shot down twelve times in 1940 "in France and the Battle of Britain" but I presume that these escapes by parachute all took place over France as I can find no details of his having fought over Britain in 1940.

This lack of information for1940 makes his score in the air uncertain, as although Baker credits him with 23.5, and Chris Shores and Clive Williams follow this in "Aces High" (Neville Spearman), neither Chris Shores nor I are by any means certain that all the victories were in the air. He credits Chris le Roux with 8 victories with No. 91 Squadron in 1941, 4 with No. 111 in North Africa, and with No. 602 in 1944, making a total of 17. He follows Baker's total of 23.5 very doubtfully, as it is made up of 9 with No. 91, 5 with No.111 and 5 with No. 602, which makes 19 and them Baker writes that Chris got "several on the ground" while with No. 91. Chris Shores and I both think that some of these may be included in Baker's total of 23.5.

However, if this is so, it would mean that although it appears that Chris le Roux baled out 12 times in 1940, that he failed to score himself. This seems most unlikely, and if anyone can help to put the record straight I should be most grateful to hear from him (or her), as it could well be that Chris le Roux's score was more than 23,5.

The first victory I can trace for him is as a Flying Officer in Spitfires with No. 91 (Nigeria) Squadron, which had been formed from No.421 Flight after this mixed bag of Hurricanes and Spitfires had done very useful work (meteorological observation climbs, coastal gunnery, spotting and security patrols) in 1940. By January, 1941, the whole squadron was equipped with Spitfires, and Chris le Roux shot down a Me 109E on 17th August, 1941, followed by another on the 29th. Before he was rested from operations he claimed four l09Fs; one on 4th September, 1941, one on 28th October and another on 11th November.

On his return to operations, the next I can trace of him is as a Flight Commander with No. 91 Squadron, when he destroyed two FW 109s on 31st October, 1942. He had by this time received both the DFC and Bar but the citations are no help in identifying his victories. He had flown more than 200 operational sorties including shipping reconnaissances, ground installation attacks, escort missions, and fighter sweeps.

At the end of 1942 he was posted to No.111 Squadron in No.324 Wing in North Africa, and became Commanding Officer of that famous squadron (known as the "Black Arrows" with their aerobatic teams of later years) in 1943. On 14th November, 1942, No.111 Squadron flew into Bone airfield, and were immediately attacked by enemy aircraft, and suffered severe casualties to both aircraft and ground crews. Christmas found the squadron at Souk el Arba, and the Operations Record Book recorded "a pretty miserable day, raining all the time and bogging the aircraft. The pilots spent the day trying to get them out and came back at dusk dead to the world." Efforts were made to lay a steel netting mat, but the long thin lines of communication meant that for a single runway, two days capacity for the entire railway system would be needed. Even when enough steel matting could be found it tended to sink into the mud and disappear. Despite these difficulties, Chris le Roux damaged a Me 109 on 14th January and another on the 19th, and destroyed yet another on the same day. On 3rd April he shot down a FW 190, and on 23rd another FW 190 and a Me 109. By May the German and Italian fighters had been swept from the Tunisian skies, the 7th Armoured Division (the famous Desert Rats) occupied Tunis and the Americans took Bizerta. The Germans finally capitulated on 12th and 13th May and the war in Africa was over. The experience gained was to serve the air forces well in Europe.

The next I can find about Chris le Roux is his having taken command of No.602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron in France in the summer of 1944, with Spitfire 9s, having received a second Bar to his DFC for his North African successes. He led this squadron through the fierce fighting of the invasion of Normandy, and moved it to French soil on 25th June. He shot down a FW 190 and a Me 109 on 15th July, 1944, and another FW 190 on 16th. On 17th he destroyed two Me 109s and damaged two more, and the squadron nearly succeeded in killing the German Commanding General, Erwin Rommel. Diving on his car, they caused it to overturn near the village of Sainte Foy de Montgomerie, and Rommel was flung into a ditch and sustained a fractured skull. He survived, only to kill himself on 14th October, rather than stand trial for complicity in the plot against Hitler of 20th July.

By 25th August, 1944, Paris had been liberated, and on 3rd September, five years after the outbreak of war, the Welsh Guards entered Brussels. Chris le Roux did not live to enjoy the fruits of the victory. Like so many gallant and brilliant fighter pilots, he was destroyed, not by enemy gunfire, but by an aircraft accident, on 19th September, 1944.

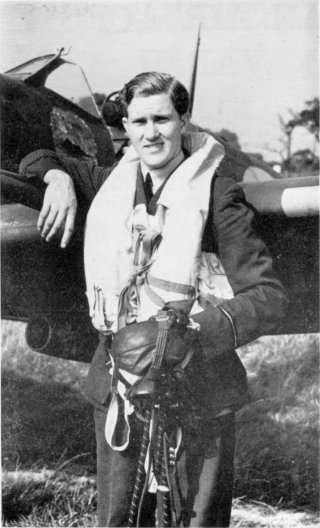

Squadron Leader J. J. le Roux, DFC

His cheerful personality and good looks had made him one of South Africa's most popular fighter pilots, and he was mourned by all who had known him. The No.111 Squadron Operations Record Book contains a magnificent "line" which remains as a fitting memory of one as young, as gallant and as gay as Chris le Roux. It quotes him as relating the story of his having made a good landing in very dirty weather and the mud described earlier, and finishes up: "I didn't realise I was down until I heard the ground crew clapping!" He was a very worthy member of "the gayest company who ever fired their guns in anger."

Group Captain P.H. Hugo, DSO, DFC and two Bars

Petrus Hendrik Hugo was born on 20th December, 1917, and his home was at Pampoenpoort, Cape Province. As a youth his sights were always set on a career in the air and he soon came north to attend the Witwatersrand College of Aeronautical Engineering. In 1938 he went to Britain, and attended a Royal Air Force course at the Civil Flying School at Sywell early in 1939. These Civil Flying Schools (of which there were 13) had been approved after the 1935 expansion of the RAF had begun. Before that all pilots who had entered the service had been trained at RAF stations, where, for eleven months, the pupil pilots had received elementary flying instruction and lectures. (Those readers who saw the profiles of Pat Pattle and Sailor Malan in our last issue will recall that they were trained in this way.) Advanced subjects like instruction in night flying, formation flying, air gunnery and bombing were dealt with when they went to their squadrons. Four of the Civil Flying Schools were already in existence in 1935 and had handled the flying training of Royal Air Force Reserve personnel for some years; five new schools were opened in the second half of 1936, and by the time Petrus Hugo came to be trained, four more had opened.

The pilots received 50 hours' preliminary flying training at these schools before they passed into the RAF to proceed to their flying station for military flying instruction as explained above. Petrus, like Sailor and Pat before him, soon received a nickname when he gained his Short Service Commission on 1st April, 1939. His Afrikaans name and accent soon earned the name of "Dutch", and thus he was known to the RAF throughout his service.

Group Captain P. H. Hugo, DSO, DFC

He went to No.13 Flying Training School for six months and at the end of the course he was deemed "an exceptional pilot, an excellent marksman and suitable for posting to a fighter squadron." He then went to the Fighter School at St. Athan in Wales, and then to No.2 Ferry Pool, Filton near Bristol. He escaped this fate in December, 1939, three months after war had broken out, and joined No. 615 (County of Surrey) Squadron at Vitry, in France. This Auxiliary Air Force Squadron was equipped with Gloster Gladiators at the time, and he had his first operational flights in these obsolete biplanes.

The weather was so bad at Vitry-en-Artois that Nos. 615 and 607 Squadrons (both part of the Northern Air Component, and both flying Gladiators) found it easier to operate from St. Ingelvert nearby. Even here, the severe frost made the muddy ruts dangerous as they froze hard, and on 18th December a pilot of No.615 Squadron was killed when his Gladiator crashed on landing. However, on 29th December, one of the Flight Commanders, Flight Lieutenant J. G. Sanders, nearly destroyed a Heinkel 111 at 23,000 feet, firing a long burst into him at close range, but no confirmation of destruction was received as the He 111 dived into cloud and disappeared.

Dutch Hugo and his fellow pilots in No.615 Squadron suffered the boredom and appalling weather of winter, 1940, doing practice escort affiliations with the Lysanders of Nos. 2 and 26 (Army Co-operation) Squadrons, but were delighted towards the end of April, 1940, when they were warned to prepare to re-equip with Hurricanes. The events following the 10th May when the Germans struck, however, were to see the old Gladiators fighting in deadly earnest, and both squadrons were constantly in action. Although no records exist it appears that by about 15th May, No.615 Squadron still flew 12 Gladiators and that by 18th these had been joined by 9 Hurricanes.

Two days later Dutch Hugo (I think flying a Hurricane) shot down a He 111, on 20th May, 1940, his first and only success with the RAF Component as far as I know.

The Heinkel 111 was a low-wing all-metal monoplane which carried a crew of five or six (pilot, bomb-aimer, radio operator, and two or three gunners). It carried five 7.9 mm machine guns, one in the nose, one in the ventral and dorsal positions, and two in the sides firing from the windows.

The Hurricane pilots were kept at full stretch, putting in as many as six, or even seven, sorties a day. Despite their efforts it was decided that the Component could operate as effectively, and with a great deal more security, from the south of England. The 21st May saw the Hurricanes return to Britain; 195 had been lost and only 66 saved. Most of the Gladiators had been lost, only one or two being flown home to England. The Luftwaffe lost 1,284 aircraft, however, and there is no doubt that a very large number fell to the RAF Component, although it had lost 279 of its own aircraft.

No.615 returned to England (most of the personnel in the steamer Biarritz from Boulogne, arriving at Dover on 21st May) and at once returned to its home stations of Croydon and Kenley (in Surrey, as befitted the County of Surrey Squadron). Re-equipping with Hurricanes continued, although there was still a Gladiator Flight at Manston until 30th May.

Like Pat Pattle, Dutch Hugo was to achieve magnificent success in the Hurricane, that grand aircraft of which Paul Gallico wrote in "The Hurricane Story":

"She was loved and trusted by every man who ever knew her. To the eyes of the young men who looked upon her with warmth and affection she had beauty unsurpassed. To her friends she was gentle, staunch, loyal, and a protectress; to her enemies she was a lightning bolt from the skies, a ruthless and total destroyer.

"She was unique in the heavens for there was nothing she could not do there when called upon by those who loved and needed her.

"An inanimate piece of machinery, a mass of tubes, wire, steel, aluminium, she flew like an angel.

"She had no vices.

"In the hands of the young men, who mastered her and became her lovers, she saved England and all that rest of the world that cherished the right of freedom.

"She was the Hawker Hurricane."

The prototype had first flown in 1935 (serial K5083) piloted by the same man, Flight Lieutenant George Bulman, who, ten years later, was to fly the last Hurricane to be produced (serial PZ865). The first production Hurricane (serial L1457) with a Merlin II engine, flew on October 12th, 1937. Unlike the prototype, it had stub exhausts, a strengthened canopy, modified rudder and different undercarriage doors. It still had fabric covered wings; metal wings and bullet-proof windscreens did not come until 1939. Even then many fabric-covered wing models were still in action in France and although it had been planned to withdraw all fabric-wing and wooden-airscrew Hurricanes from service with operational units by May, 1940, the losses in France meant that many of the older machines served on in the squadrons. On July 4th, 1940, 82 fabric-covered Hurricanes were on combat squadrons, and 36 had wooden propellers. Ten days later, on 14th July, 1940, Dutch Hugo shot down a Junkers 87, flying his Hurricane from Kenley.

The Ju 87 Stuka (dive-bomber) had swept a path for the armoured divisions through France and Poland but was no match for the Hurricanes and Spitfires over Britain. It carried a crew of two and had two fixed and one movable machine guns.

On 20th July, 1940, Dutch Hugo gained his second success in the Battle of Britain, shooting down two Me 109 fighters. The Me 109 was undoubtedly one of the finest single-seater fighters in the world at that time, and had a top speed of 354 m.p.h. at 12,300 feet and a cruising speed of 300 m.p.h. this was about 40 miles faster than the Hurricane at 12,300 feet, yet at its own rated altitude of just over 15,000 feet the Hurricane was at least a match for the German fighters provided they did not start with height advantage. The Hurricane was therefore usually used against the slower, lower-flying bombers, but despite this Dutch Hugo shot down yet another Me 109 on 25th July, and shared a Heinkel 59 floatplane with another pilot on 27th. The British Government had decided that it could not recognise the right of He 59s to bear the Red Cross, since it was probable that these aircraft were being used to report movements of British convoys, and a fortnight before had instructed British pilots to shoot them down. A Heinkel 59 had been seen leading Me 109s (despite its Red Cross markings) at sea level, and had been forced down on July 11th by Al Deere of No. 54 Squadron (there is a good photograph of this aircraft in his book "Nine Lives" (Hodder & Stoughton)).

On 12th August Dutch shot down another Me 109, the Combat Report reading: "Dense smoke and liquid poured from the German pilot's machine. Although my engine stopped I dived after him. Fortunately my engine restarted. The Me pilot pulled out of his dive at about 6,000 feet and then started to dive again. I was hot on his tail and at about 3,000 feet opened fire. The German pilot continued to dive and landed in the water. Within a minute the aircraft had sunk, and I saw the pilot swimming about in the middle of a big patch of air bubbles which had been caused by the sinking of his machine. I sent back a message on my R/T asking for a launch to be sent out to the German airman's rescue and gave his position. I then flew to base."

On 16th August Dutch claimed a Heinkel 111 probably destroyed over Newhaven, but was himself hit by cannon shell splinters from a Me 110. He was slightly wounded in both legs, but was back in action again two days later. The Germans bombed Kenley and he took off with a number of other Hurricanes to intercept the raiders, only to be "jumped" by a number of Me 109s. He was wounded in the left leg, left eye and his right cheek and jaw, and his Hurricane was so badly damaged that he crashed-landed, and was taken to Orpington Hospital, near Biggin Hill. He was still there, in the shadow of the copper beeches and the railway arch, at the end of August, 1940, when the award of the DFC was announced.

By the end of September he was fit again and rejoined No. 615, by then at Prestwick in Scotland. He returned south for convoy patrolling in the spring and early summer of 1941 but it was late summer before he met the Luftwaffe in action again. By that time, back at Kenley with Hurricane 2cs with four cannons, he was a Flight Commander, and led raids on enemy shipping, and coastal installations in Northern France. Between 18th September and 27th November he helped to sink over twenty ships and damage a further ten. On 14th October in a raid against the seaplane base at Ostend, he shared another He 59 with his CO, and on 27th in another attack on the same place, he shared yet another He 59 with two other pilots. He was awarded a Bar to the DFC on 5th November, the official citation paying tribute to his great skill and determination, his high qualities of leadership and courage and his unabated enthusiasm.

Towards the end of November, 1941, he took command of No. 41 Squadron, flying Spitfire 5s, from Manston, on sweep duties. On 12th February, 1942, the German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau broke out of Brest harbour, and he shot down one Me 109 and damaged a second in a battle with 20 Me 109s over the escaping ships. On 14th March he shot down another 109 over a German convoy near Fecamp, and on 26th he got another escorting Bostons raiding Le Havre. He was truly the scourge of the Me 109.

Promoted to Wing Commander, he took over the Tangmere Wing, but less than a fortnight later, he was wounded again, being shot down in the Channel. This was on 27th April, in a battle between Dunkirk and Cap Gris Nez. In a fierce running fight he got a probable FW 190 and damaged a second but was hit in the left shoulder, and had his aircraft so badly damaged that he had to bale out, luckily being picked up fairly soon. He was awarded the DSO while recuperating at 11 Group HQ, and the London Gazette of 29th May carried the citation crediting him with 13 kills (some shared) and concluded: "Both as Squadron Commander and Wing Leader this officer has displayed exceptional skill, sound judgement and fighting qualities which have won the entire confidence of all pilots in his command."

He "escaped" from HQ after a couple of months and took over the Hornchurch Wing, but soon left to join No.322 Wing in North Africa, in November, 1942. On 12th he and Shag Eckford shot down a Dornier 217 near Djidjelli. (It will be recalled that Chris le Roux arrived with No. 111 Squadron on 14th November.) The 13th November saw Dutch credited with a probable Ju 88 and another damaged near Bougie Harbour which our forces were approaching. On 15th he got a probable He 111 and a damaged Ju 88 over Bone Harbour, and on 16th he got a Ju 88 and two Me 109s. He got another Ju 88 on 18th and three more Me 109s on 21st, 26th and 28th November, 1942. The scourge of the 109s was at it again.

On 2nd December he shot down two Italian Breda 88s near La Galite, one being shared, and on 14th he got a Savoia 79 over the cruiser Ajax. He had taken command of the Wing on 29th November, and led it for the next four months until he was posted to HQ NWACAF (North-West African Coastal Air Force) and awarded a second Bar to the DFC.

He returned to command No.322 Wing in June, 1943, and on 29th destroyed yet one more Me 109. On 25th, 33 Spitfires of the Wing, operating from Lentini, had slaughtered 21 Ju 52s and four Messerschmitt fighters. Twelve of the Ju 52s had been shot down in flames, exploding as they went, for they were loaded with petrol, and were circling to land near Milazzo in Sicily.

On 2nd September Dutch Hugo shot down another FW 190 near Mount Etna and on 18th November he got his last confirmed victory of the war, an Arado 196 Floatplane, over the Yugoslavian coast.

During the summer of 1944 he led the Wing in a series of most concentrated attacks against enemy transport and supply, accounting personally for at least fifty-five vehicles destroyed and a further twenty-nine damaged in less than six weeks in May and June. On 10th July he damaged a Me 109 over Northern Italy, and brought his score to twenty-two destroyed, four probables and thirteen damaged. In November, 1944, he was taken off operations and posted to HQ Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, and was then seconded to the Russian Second Ukrainian Army under Marshal Tolbukin, at that time moving from Roumania to Austria.

The last I heard of him was when, having reverted to Squadron Leader from Group Captain at the end of the war (most officers had to drop a rank or two from their wartime ranks to become peacetime substantive) he was posted to the Central Fighter Establishment. He retired as a Squadron Leader, retaining the rank of Group Captain, in February, 1950, and settled in East Africa. All efforts to get in touch with him have failed, but if any of our readers knows this most gallant and successful fighter pilot's present address I should be very pleased to give him the opportunity to correct any mistakes in this profile, and if possible, to get him to write his own story for this Journal. His modesty will no doubt keep him silent, but he remains the top-scoring surviving South African fighter ace of World War II.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org