The South African

The South African

by DR G.A. CHRISTIDIS

He was indeed a prophet for no battle has become so famous, so celebrated, so advertised, so written up, discussed or talked about as the battle of Waterloo.

Napoleon was also right in that the battle saved France, not however from her enemies, but from his vainglorious and bloodthirsty stranglehold.

Whatever the political implications involved, the remaining male population of France was spared a last tortuous and torturing bloodletting which would undoubtedly have occurred had Napoleon won the battle.

It is a sad corollary of history that the Battle of Waterloo was devoid of any strategical significance whatsoever, which in plain language means that, had Napoleon, the so-called God of War, won that battle, it would have made no difference at all on the war as a whole, nor to his ultimate fate, for that matter.

France in those days with an approximate population of 28 million was almost the most populous nation of Europe. Russia was somewhat more populous if we include all its Asiatic peoples from Catherine the Great's recent conquests. On the other hand England, Scotland and Ireland (who were providing a lot of professional soldiers in those days) had a population of between 16 and 18 million.

France, first under the Revolution and later under the greatest egotist of the world, Napoleon, glamourized as the God of War and as the genius of victory, was waging war and fighting all over the world for 25 years. Under Napoleon, France had lost whole armies, first in Egypt, then in the expedition under General Leclerc against the Negro revolt in the island of Haiti in the Caribbean.

She lost more than one army trying to subjugate the proud Spaniards.

The half a million strong Grand Armee (the military wonder of the early nineteenth century), three hundred thousand of which were Frenchmen, was completely annihilated in Russia in 1812.

In 1813 Napoleon, nothing daunted, scraped the manpower barrel of France, raised new armies and against any and all military logic (while the four-year war against the aroused people of the Iberian peninsula was draining the life-blood of the country away) invaded Germany, trying to keep Europe subjugated. In a series of battles he lost another big army, so that during 1814 he did not have enough troops to ward off the invading allies.

Came his resignation and confinement with all honours to the adjacent little island of Elba.

By that time not a family in France was without one or two victims of his insatiable ambitions for conquest and glory. The French mothers were referring to him as "the monster" and as the ogre that was devouring their offspring with his incessant campaigns.

It was the wanton sacrifice of the young French manhood by Napoleon that brought France, the most prosperous and most populous country of Europe, to the status of a second-rate power during 1870, 1914 and 1940 when she was forced to fight for her very existence.

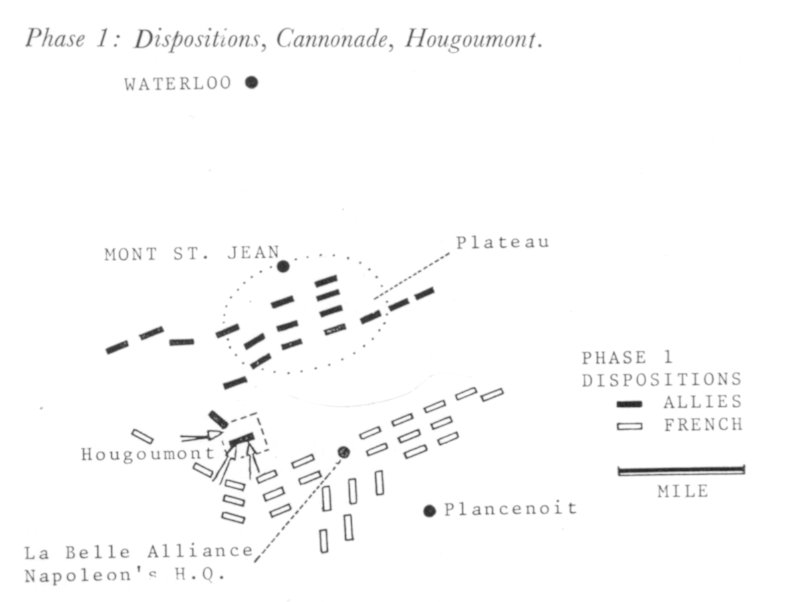

Phase 1: Dispositions, Cannonade, Hougoumont.

Once Wellington decided to accept battle he deployed his heterogeneous army on the softly rising plateau of Mont St. Jean and projected a few battalions on his advanced right to defend Hougoumont Castle, farm buildings, woods and other features.

It was behind Hougoumont that the imaginary precipice and the imaginary hollow road that destroyed Ney's cavalry, were supposedly located, all widely and universally believed myths emanating from the pen of Victor Hugo and other writers. Myths and legends that have no basis on topography nor on military facts.

Since the most obstinate part of the battle and most of its casualties took place on that plateau of Mont St. Jean, the battle itself should have been called the Battle of Mont St. Jean. Wellington, however, called it the Battle of Waterloo, from a little village in the rear of his deployment, which one of his staff officers could not even find on any map!

The British Army did not construct breastworks. The reason for that is unknown, therefore we leave it at that. Wellington had an Allied Army (British, Dutch and German) of 65,000 against Napoleon's homogeneous 74,000.

Napoleon's army was made up of veterans mostly from the remnants of his destroyed armies, from released prisoners of war and especially from repatriated garrisons of fortresses that were abandoned.

Those veterans were devoted to Napoleon and were brave warriors. In fact they were the best soldiers in Europe, but they were not many and on that day they did not have the best leadership. Napoleon's cavalry of 15,000 was particularly strong and well mounted, but had no real leader, for Murat was refused employment. He was also very strong in artillery and he was the undisputed master of that arm.

On the other hand Wellington had an heterogeneous Allied Army and fewer guns. But he was a master of the defensive battle, even though Napoleon did not agree with that assessment.

General Reille, who knew Wellington, his tactics and his infantry well from the disastrous campaigns in Spain, told Napoleon: "The British Army in a defensive position is impregnable. Before crossing bayonets with them half the assailants will be shot down."

Napoleon ridiculed his opinion adding that, "on the contrary the British Army is very inferior to a French army, if that army is properly commanded."

Originally Napoleon intended to attack very early, for he was worried lest Wellington would slip away. But the ground was soft and slippery on account of the night's heavy downpour. Another reason for the delay was that the French army was dispersed from the previous battles and pursuits against Wellington at Quatre Bras and Blucher at Ligny. But the most important reason for the dispersal of the French army was the total absence of any commissariat.

Napoleon waged all his campaigns on the principle that each of his divisions would fan out, to plunder and live on the countryside, without any other expense, bother or cumbersome commissariat organization.

For the above reasons, instead of beginning early in the morning, he opened the attack at noon.

The battle itself was simple and easy to describe. No complicated movements, no brilliant conceptions, especially from the defeated side. Napoleon's tactics were the same as in many previous glorious victories. Heavy, continuous and well-directed bombardment by his guns. After the hoped for decimation and demoralization of the enemy, frontal assault by the bayonet and finally pursuit and annihilation.

His artillery concentration against the plateau that Sunday at noon was terrifying. As a matter of fact thousands of Wellington's raw Allies withdrew from their positions and simply took cover behind the battle line among the woods to the east of the unknown insignificant little village of Waterloo.

A staff officer described the troops who found refuge in those woods as a Sunday picnic crowd out of harms way. But that withdrawal was a blessing in disguise for Wellington, for he was left with a smaller army composed of well-disciplined and battleworthy troops, over a small compact area, and over whom he exercised perfect control throughout the crisis.

Napoleon's heavy guns with a range of over 2,000 yards were particularly effective, but Wellington changed the positions of some of his veterans on the plateau and in that way prevented very heavy casualties. That and the heavy ground prevented the cannonade from being decisive. During the previous night it had rained a lot and the round shot of the French artillery instead of rebounding on hard ground was getting stuck in the mud among the tall cornfields.

Nevertheless, only well-disciplined veteran infantry like the Peninsular veterans could have withstood that onslaught without budging from their allotted positions.

The first infantry attack went against the Castle, farm and surrounding outbuildings of Hougoumont, which were jutting out on Wellington's right front.

General Reille's veterans there met the British Guards. The battle was fierce and unrelenting, lasting over six hours. Jerome (the progenitor of the American Bonapartes) and General Reille repeatedly threw in reinforcements, but Wellington, husbanding his meagre resources, added a company to every additional regiment of the attackers. The farm houses of Hougoumont and the surrounding stone walls, hedges and woods changed hands a number of times during the struggle but when the crisis of the whole battle arrived late in the afternoon, Wellington felt confident that his right would not give in.

This phase of the battle in and around Hougoumont was a pure and simple savage clash of infantry with hardly any significant participation of the other arms.

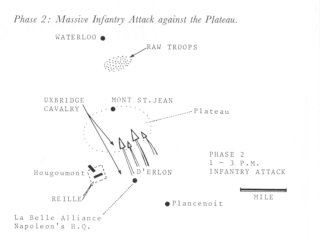

Phase 2: Massive Infantry Attack against the Plateau.

Around one o'clock rising dust clouds were perceived towards the French right. Napoleon hoped that it was Marshal Grouchy hastening to his aid. Very soon however it was established that they were Bulow's corps of Prussians.

Right then and there any sensible commander would have broken off the battle. Not Napoleon. Firstly, because he was a gambling egomaniac believing explicitly in his lucky star and secondly, because he knew that there was no chance of beating the Anglo-Prussians once they joined forces and while the Austrians and the Russians were marching, slowly but inexorably, against France.

He proceeded, therefore, with the battle and ordered his infantry, aided by cavalry, to attack the British centre on the plateau of Mont St. Jean.

It was an awe inspiring advance of D'Herion's infantry, in four dense columns, with drums beating and 16,000 veterans shouting.

The British guns did great execution against the massed attackers, but the centre on the plateau was nevertheless pierced.

While Wellington was trying to steady his line, Lord Uxbridge at the head of the British heavy cavalry hit the French cavalry and drove it pell-mell against D'Herlon's decimated infantry. In a few moments the splendid 16,000 French infantry were routed and retreated from the plateau with the British cavalry slashing at them in a heedless and headlong frenzied pursuit.

But the British cavalry, no matter how dashingly ridden or how splendidly mounted, was not like Frederick the Great's superb arm. They did not stop for they could not stop in time and reaching Napoleon's reserves and plentiful cavalry they were practically destroyed and ceased to count for the rest of the day as a fighting factor.

Nevertheless, Wellington's centre on the plateau was relieved and he proceeded to strengthen it by denuding his right wing of the troop he had posted there previously about a couple of miles behind Hougoumont.

By that time he felt certain that his guards would hold Hougoumont Castle, where the battle was raging all the time.

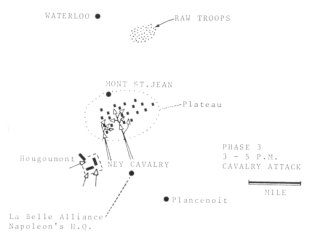

Phase 3: Marshal Ney's Cavalry Advance.

Marshal Ney mistook a 100 yard move to the rear by Wellington's centre as a preliminary sign of retreat and ordered the advance of his cavalry, especially his Cuirassiers.

It was a magnificent sight, as Wellington often admitted later on, but utterly suicidal, as he then thought, against unbroken British infantry.

The charge of the French cavalry was not a headlong gallop, as the popular imagination would have it. On the contrary it was a slow but disciplined uphill trot. When they showed up on the plateau the British gunners took a terrific toll and then retired in the middle of the 20 squares that the British infantry had formed, on Wellington's orders.

The 20 squares of 500 bristling bayonets each presented a formidable problem, for they kept pouring a murderous fire against the cavalry that had surrounded them. There were no death defying charges against the bristling squares as the chroniclers and poets would have us believe. The long bristling bayonets at the end of the long-barrelled rifles of the period prevented that. But there were a lot of rifle and pistol discharges against the squares, especially from the French skirmishers and every centre of every square was filled with dead and dying. But their indomitable steadfastness defied everything.

It was then that Marshal Ney (the bravest of the brave, but no great strategist) asked Napoleon for infantry. The Emperor's message to the Marshal was "where does he think I can find them?"

During most of the afternoon the Emperor was almost in a stupor and did very little personal, vigorous, directing of the battle. It is well understood that, had French infantry (13,000 choice Imperial Guards, the apple of Napoleon's eye, were inactive) and mobile artillery reached the plateau of Mont St. Jean while the British were in squares, they would have blasted them out of existence.

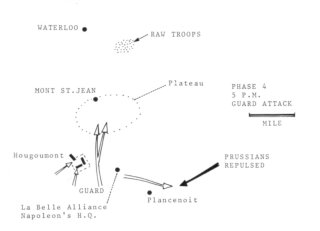

Phase 4: Repulse of Bulow and Attack of the Guard.

Around 5 o'clock the first Prussians of Bulow's corps reached the battlefield on Napoleon's right rear and attacked the little village of Plancenoit. This time curt, peremptory, specific orders were given to the Imperial Guard: "Don't fire, charge and drive the contemptible Prussians away with the bayonet."

The Guard did just that and von Bulow's corps was driven away and retired a few miles to return to the attack a few hours later.

Marshal Ney in his repeated charges lasting over two hours used up 15,000 of the best cavalry of Europe but though the British squares were sorely tried, made no impression on them.

By this time the plateau of Mont St. Jean was a ghastly sight full of dead, dying and wounded men and horses. Casualties were practically 100% with Wellington's senior officers and though he was ranging the compact field from one end to the other he was spared.

Around 7 o'clock Napoleon finally made up his wavering mind to reach a decision and ordered a frontal attack by his splendid guard against the plateau. That attack was preceded by the usual concentrated cannonade, for by that time Ney's decimated, worn out and tired cavalry had retired from the plateau.

The British infantry broke the squares and deployed to meet the attack. The British gunners once again took another heavy toll, while the infantry blasted at them at point blank range with murderous, disciplined, and well-directed volleys.

While Napoleon's Imperial Guard was trying desperately to hold their own in a titanic struggle of heroic experienced veterans against equally obstinate and heroic troops, a second corps of Prussians under General Ziethen made their appearance on Wellington's left and immediately attacked.

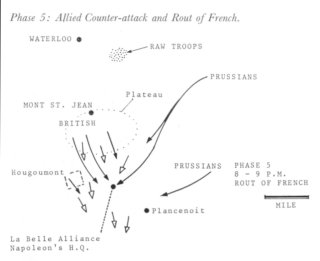

Phase 5: Allied Counter-attack and Rout of French.

Courage, bravery and tenacity were superb on both sides on the plateau.

Finally, Wellington, with a great sense of timing, gave the sign of a general advance by raising his hat on his sword and the whole line (or rather the intact survivors) charged

forward.

Napoleon's Guard resisted desperately but they were carried back, they were surrounded and in the waning twilight were killed or captured. General Cambronne who, according to literary lore (against military facts), won a moral victory by uttering the French word to a demand for surrender (a slang equivalent to McAuliffe's reply in Bastogne during the battle of the bulge), was captured and during that night Wellington refused to have dinner with him in the staff mess, because he thought him a traitor to his King, Louis XVIII.

Practically in darkness now the converging victorious Allies, British and Prussians, met at Napoleon's little knoll, La Belle Alliance, where he had his headquarters during the day.

The Prussians took up the pursuit while the exhausted survivors among the British tried to collect prisoners and look after the thousands of maimed and wounded on the battlefield.

Fifteen thousand British casualties and 40,000 French covered the 2.75 square miles of the sanguinary battlefield, filling the night with the indescribable horrors and sufferings of the fallen in an early nineteenth century battle where amputations without anaesthetics were the procedures on serious wounds.

After the Napoleonic wars, with no Social Security nor State care for the cripples, the most common sights all over Europe were the miserable maimed cripples eking out a pathetic existence, mostly from begging. Twenty-five years of incessant war for conquest had filled Europe, and England as well, with these pitiable sights of continuous human degradation and suffering.

Conclusion: Waterloo had no Strategical Value.

Let us then leave the horror of the legendary battlefield, let us leave the complete destruction, both physically and morally, of the last veteran Napoleonic army and expound on the thesis that this bloody battle had no strategical significance whatsoever.

Let us assume that, instead of the Prussians coming to the aid of Wellington, it was the wandering Marshal Grouchy, with his 30,000 troops, who fell on Wellington's left flank, instead of the Prussians attacking Napoleon's right as it actually happened.

Marshal Grouchy is the scapegoat of all good and true Napoleonic apologists. It has historically been proven, however, that Wellington took up a defensive position on the plateau of Mont St. Jean and offered battle on the explicit promise of the indomitable Grand Old Man of the Prussian army, Field Marshal Blucher, that he would rush to his aid, come what may.

Well then despite Wellington's hopes, wishes and plans (many a time afterwards he said that "the famous battle was a very near run darn thing") and Blucher's promises (not shared however by his unenthusiastic Chief of Staff, Scharnhorst) let us repeat that had Grouchy, during the crisis, arrived and attacked the Allied army, there is no doubt it would have been completely destroyed. Its remnants would retreat towards Ostend, picking up the 20,000 troops previously left at Val for the purpose of protecting that very route. The Peninsular veterans who were returning from the unhappy American war of 1812, would have joined them at Ostend and shortly Wellington, in case he had survived (something rather improbable but nevertheless possible), would have had another professional army of 50,000 to take the field again.

During the crisis of the Battle of Waterloo on the plateau one of Wellington's officers watching the carnage and the unprecedented slaughter, started wondering if there ever was a battle in history where there were no intact survivors!

On account therefore of the above facts and the desperate struggle on the plateau, Napoleon's victorious but half-destroyed army, after the Waterloo battle, would have to face 130,000 practically intact Prussians (the Ligny battle casualties would have been made good) plus the slowly approaching 200,000 Austrian and Russian troops inexorably marching on France and on Napoleon, whom the Congress of Vienna had declared an outlaw and an enemy of peace.

Under the above military facts and circumstances one or two small-scale battles would have been expected and Napoleon's fate would have been the same, except for a much bigger devastation of France by the invading enemies.

If history had taken that course, the battle of Waterloo would have been one more glorious but barren victory for Napoleon, the God of War, on which the apologists and the poets could not make such a fuss or legend. And for another thing, Wellington would have been rated just another good general, unable however, to join the exclusive club of that unbeaten triumvirate, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar and himself!

EDITOR'S NOTE:

Dr George Christidis was born in Yiannina in Greece and studied dentistry in Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. The second world war found him practising dentistry in Athens and when he was mobilised he acted as interpreter for 112 Gladiator Squadron, R.A.F., which was then operating against the Italians. When Germany attacked Greece the Squadron was virtually wiped out and Dr Christidis was kept busy helping ground crews escape to the Middle East.

In the Middle East he joined the Royal Hellenic Air Force and became the Adjutant

of the only Greek Bomber Squadron operating from the great Gambut airfield near

Tobruk. Ultimately he was transferred to South Africa where the Greek Air Force

was training cadets in various training centres of the British Government. He was

the last Greek Liaison Officer in South Africa where he was demobilised and where

he has since been living. His hobbies are military history, speechmaking with the

Toastmasters, and world travel. The article reproduced above was originally

presented in the form of an address to the South African Military History Society

at its monthly meeting held at the South African National War Museum on

Thursday, 14th September, 1967.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org