The South African

The South African

by J.A. BALL

"Mr. Chairman, I thank you and your Society for the invitation to address you this evening ... and whilst I do so with some trepidation I hope you will find what I have to say of some little interest in our military history. I must say at once I do not profess to be an expert ... or even an authority on the subject of my address ... but I do know that the moving genius in the achievement of the P.O.W. Administration here was the late Colonel Hendrik Fredrik Prinsloo, O.B.E., E.D., eldest son of the Spioenkop hero*, Commandant H.F. Prinsloo, of Carolina Commando and Boer war fame.

On returning from the East African and Middle East campaigns I spent some three and a half years "in captivity" at the Zonderwater Camp and there saw much of the achievement in the field of human relations of which I will now try to speak.

It was in February, 1941, almost 26 years ago today, that the first Italian prisoners-of-war arrived in South Africa. As time went by increasing numbers taken "into the bag" by our Springboks in the Italian Somaliland and Ethiopian campaigns began flowing in. These, followed by the thousands who throughout the years 1941 to 1943, poured into South Africa from the Desert campaigns in Egypt, in Libya, in Cyrenaica and in Tripolitania, constituted a major problem in view of their considerable numbers.

Transport, clothing, housing, feeding, security, and hospitalisation became major headaches. Most of you who know what is involved in the administration of very large bodies of men suddenly concentrated together have some idea of what this can mean. And when I say that we in South Africa were not ready, we were not organised for, we were not expecting, such large numbers so suddenly, you will understand the magnitude of the local problem facing South Africa.

Very naturally there was at first a certain amount of confusion and disorganisation. In the suddenness with which we were confronted with the problem this was only to be expected.

Later, however, order evolved out of near-chaos ... and at Zonderwater, some 23 miles from Pretoria, there grew up what was to become, I believe, the largest single Prisoners-of-War Camp throughout the Allied territories.

When completed the "Camp" (!) consisted of 14 Blocks, each Block having four camps. In addition there was a Transit Camp, a disinfestation Camp, and a P.O.W. hospital which, whilst it was never full, had some 1,600 beds making it at that time one of the largest (bed capacity) hospitals in South Africa. You can imagine the volume of the hutments and other buildings required and necessary to accommodate such a large concentration of captive humanity.

To put it briefly, from 1942 onwards Zonderwater P.O.W. Camp was as large, white population-wise, as the then town of Benoni on the East Rand! There were more than 24 miles of roads within the prohibited area of the Camp!

The Permanent Exhibition Hall, Central Library, and

Welfare Organisation Offices at Zonderwater Camp.

At the onset accommodation for both the South African staff and the prisoners was in tents. A vast tent town had arisen virtually overnight as it were. Later solid hutment accommodation was built of clapboard, brick, concrete and corrugated iron. The labour used was largely that of the P.O.W. themselves. In time electric lighting was installed throughout and the whole perimeter was floodlit at night.

As you know, the conditions of detention of prisoners-of-war do not depend entirely on the goodwill of the Detaining Power or its Agent Country. Certain specific minimum conditions are laid down by the Geneva Convention of 1929, a document which has been referred to as "the greatest Gentlemen's Agreement of all time.' During World War II South Africa was the Agent of the Detaining Power, that Power having been Great Britain. Maximum standards are not prescribed and any betterment or supplementation of the laid down standards of treatment and detention depend upon the good graces of the Detaining Power and/or its Agent, in this instance, South Africa.

Under the Geneva Convention, Switzerland was designated the Protecting Power, and the International Red Cross which has its headquarters in that country, together with the diplomatic representatives of Switzerland in South Africa maintained at all times a watching brief to see that the minimum standards provided for by the Convention were observed.

One of the first problems to be tackled was the very important field of hospitalisation. In this great strides were rapidly made and within a short while a very well equipped and staffed hospital was established under the direction of the then Director General of Medical Services to the Union Defence Force.

This hospital, staffed by both U.D.F. and Italian P.O.W. Medical Officers and personnel, was a model of its kind and without equal in P.O.W. camps anywhere. Equipment was of the best available and the operating theatres and staff were capable of catering for most of the general medical and surgical treatments necessary. It was situated within a separate enclosed area only some three miles from the Camp Headquarters Administration and the Main P.O.W. Camp.

Each Block had its own clinic under an Italian P.O.W. Medical Officer functioning under the direction of the Main Hospital, and at these clinics the daily minor ailments were treated, all more serious cases being referred to the Main Hospital.

Camp Hygiene was, for so vast a concentration of humanity confined in what was relatively a small area, a major worry. This problem too was successfully overcome. Clarifloculators were built and a complete and most efficient sewerage system installed. The high standard of hygiene instituted and maintained throughout the history of the camp was one of its most remarkable achievements.

A large area of some 40 morgen of irrigated, and 270 of unirrigated land adjoining the Camp, all of which had previously been fallow ground that had, I believe, been classified as unproductive, was put under cultivation under the supervision of a U.D.F. officer who had agricultural experience. P.O.W. labour was used exclusively and within a short while this farm was regularly producing a wide variety of vegetables, including field crops. All its production, and I believe some records for production per acre were achieved, was used in P.O.W. feeding.

In the field of religion and spiritual comfort it will be understood that the P.O.W. population, being Italian, were some 95 per cent Roman Catholic. Spiritual needs were administered by 23 Italian P.O.W. Chaplains, and a profound interest in this field was always taken by the Apostolic Delegate in South Africa who frequently visited the camps. Several delightful small chapels were built by the P.O.W. and the mural decorations in the interior were of a high order.

One of the greatest and most lasting achievements was in the field of education. Through the medium of the Duca d'Aosta and H.F. Prinsloo Schools, established and conducted under the direction and patronage of Colonel H.F. Prinsloo, O.B.E., E.D., the Commandant of the P.O.W. Administration at Zonderwater, some 9,000 P.O.W. who, when taken captive were illiterates, learned to read and write their mother tongue, Italian, at Zonderwater in South Africa!

All forms of sport were catered for and each Block had its football ground, tennis courts, bocce (bowls) pitches and pallavolo (netball) courts. Frequent athletic meetings were held and championship tournaments organised. A football league was run and boxing tourneys were a regular feature of camp life. All this was controlled by a U.D.F. Sports Officer and his Italian P.O.W. Staff, under the Camp Administration.

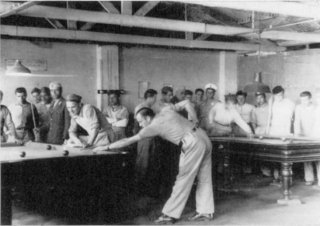

Time to relax . . . . billiards tables on Block 1.

Art, theatre, and music formed a pre-eminent part of camp life. Each Block had its P.O.W. built theatre and its theatre company. Some of these theatre companies numbered as many as 120 men. The standards of performance reached were very high indeed, and when one bears in mind that all the scenario, the backcloths, settings, costumes, decoration, lighting and so on were improvised by the P.O.W., with great ingenuity, using such materials as were to hand, it is realised what a credit it was to their artistic ability. Such world-famous operettas as Frans Lehar's 'Count of Luxembourg' and 'The Merry Widow', Kalman's 'Czardas Princess', Jones' 'The Maid of the Mountains' and many others were produced. Many straight plays including among others Rostand's 'Conte di Brechard', John Steinbeck's 'The Moon is Down', and many reviews, musical shows and variety concerts were a regular feature of camp life. Most of the then leading personalities in the South African world of art and theatre attended special performances given in aid of various charities.

A scene from "The Count of Luxembourg",

one of the Franz Lehar operettas produced in the Camp.

The cast is all male . . . . believe it or not!

Every Block had its own band of from 16 to 30 players and a combination of the best elements of these were welded together to form a symphony orchestra of some 86 musicians. A further combination produced a top-quality brass band of 65 instrumentalists.

In the limited time available it is not possible for me to cover all of the ground on the subject of my address to you this evening. It may, however, illustrate part of the value of South Africa's achievement in the field of enemy P.O.W. Administration when I say that, during the six years of their captivity in South Africa:

Some 9,000 analphabete peasants learned to read and write Italian.

Some 5,000 learned trades. (They were tradeless 'contadini' when taken prisoner).

Some 15 schools were established and maintained in the Blocks, the average attendance during the scholastic year having been 10,000 pupils.

A central library containing over 10,000 volumes was maintained, while each Block had its individual branch library.

Cinema shows and radio diffusion were regular and popular features in all the Blocks.

The total number of prisoners held in South Africa was 67,000 (at 31st December, 1942).

The largest number held in Zonderwater Camp at any one time was 63,000 (at 31st December, 1942).

Four thousand South African employers provided employment (mostly agricultural labour) to prisoners-of-war from the Zonderwater Camp alone ... during that period when outside employment on the farms was permitted.

Two hundred and thirty-three P.O.W. died in captivity (from illness). Seventy-six P.O.W. died in captivity (from accidents). These two figures combined represent a little more than half of one per cent of the total P.O.W. held in South Africa.

I have skimmed superficially over the subject but I think it must be apparent to all from what I have said, that what was achieved here in South Africa represents a very fine achievement in the field of human relations in the treatment of prisoners-of-war: and one that stands greatly to South Africa's credit for all time."

(EDITOR'S NOTE: Recognition of these achievenunts was signified when the late Colonel Hendrik Fredrik Prinsloo, O.B.E., E.D., who was Camp Commandant at the Zonderwater Camp from the beginning of 1943 until the closing of the Camp in February, 1947, and three of his officers, including Captain Ball, were invested with the Order of the Star of Italy by the post-war Italian Government with the approval of the Chief of the General Staff of the Union Defence Force. Yet further recognition came when His Holiness the Pope conferred upon Colonel Prinsloo the "Ordine di Bene Merente", that is the Papal Decoration, the Order of Good Merit.)

* see addendum to the article Forty-seven years after Spioenkop in this same Journal

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org