The South African

The South African

by Nick Cowley

The ordinary soldier of the First World War - younger than typified by Old Bill of MOTH Club fame (pic 1) -endured hardships that are well documented.

Picture 1

I ask you to imagine you are a battle-worn private soldier moving around your boggy billet on duckboards (pic 2), unwashed for several days, wearing a filthy and tattered uniform.

Picture 2

You are granted a few hours' respite in that freezing, lice-ridden billet before you are sent back to the horrors of trench warfare. One of your chief means of keeping up your spirits is by singing a whole range of songs, ranging from the bawdy to the beautiful, the not-quite-nice to the nostalgic, and I will try to provide some context and background for those we'll be singing tonight.

But first, a joke from my conservation interests, as it leads seamlessly into my topic. An endangered species had become so rare that its original name had been forgotten and it was known only as the 'rary'. The last two male raries were battling for the favours of the last female, and one male had the other trapped against the edge of a cliff plunging down into a deep and steep gorge. The trapped male begged the other one for its life, pleading "Please don't push me over the cliff." The other rary said "Why not?" and the trapped one said "Because it's such a long, long way to tip a rary."

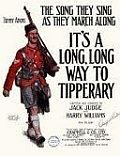

The song's close association with war is in fact an accident of historical timing, as it first emerged in the London music halls in 1913. The full version of the song features an Irishman named Paddy who's moved to London to make his fortune from its supposedly gold-paved streets; but back in County Tipperary, his sweetheart Molly is fed up and threatening to marry his rival Seamus, so Paddy is really lamenting an almost lost love. The following year when millions of men marched off to war and knew they'd be separated from their loved ones, the song caught on like wildfire. An Irish regiment, the Connaught Rangers - see here (pic 3) are recorded as singing it on August 10 1914, just days into the war, as they marched to embark for France. Let's sing it:

Picture 3

It's a long way to Tipperary,

It's a long way to go.

It's a long way to Tipperary,

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye, Picadilly,

Farewell, Leicester Square!

It's a long long way to Tipperary,

But my heart's right there.

That's the wrong way to tickle Mary

That's the wrong way to kiss.

Don't you know that over here, lad

They like it best like this.

Hooray pour Les Francais

Farewell Angleterre.

We did not know how to tickle Mary,

But we learnt how over there.

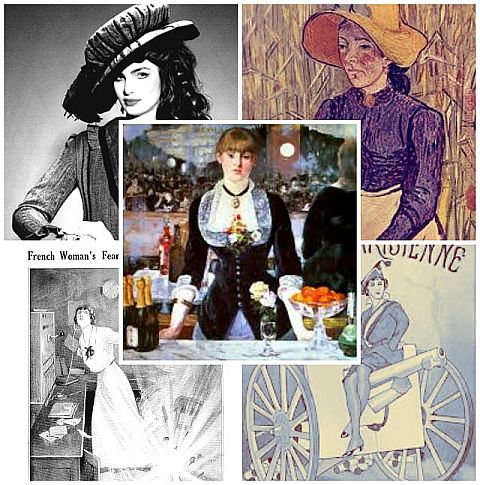

Picture 4

On top and middle we have three pre-war paintings by Renoir, Van Gogh and Manet. The lower two prints are from the First World War - the left one depicting a real incident when a switchboard operator remained at her post under fire, As for the patriotic 'lady' mounted on a cannon, she's showing a great deal of leg for 1916, and one imagines her job was to 'comfort' the troops.

Interaction between such French girls and British soldiers inspired some ribald songs. A famous one originated with a bawdy French air about the behaviour of 'Three Prussian Officers' who were part of an invading army in the 1870 war, or possibly an earlier conflict. The British got hold of this and rendered it into an equally ribald English version, keeping the blame for civilian abuse on the Germans. The repeated 'Parlez-vous' reflects the efforts to speak each other's languages as well as, no doubt, a handy pick-up line for the British soldier in France. As this is a respectable Society, we'll sing only the first verse - skipping what happened to the landlord's daughter and later the Devil - and the French women will only be 'kissed'. OK

Three German officers crossed the Rhine, parlez-vous

Three German officers crossed the Rhine, parlez-vous

Three German officers crossed the Rhine,

They kissed the women and drank the wine,

Inky-pinky parlez-vous (X2)

Mademoiselle from Armentieres, parlez-vous

Mademoiselle from Armentieres, parlez-vous

Mademoiselle from Armentieres,

She hasn't been kissed for forty years,

Inky-pinky parlez-vous.

The Colonel got the Croix-de-Guerre, parlez-vous

The Colonel got the Croix-de-Guerre, parlez-vous

The Colonel got the Croix-de-Guerre,

The son-of-a-gun was never there!

Inky-pinky parlez-vous.

Mademoiselle from Agincourt, parlez-vous

Mademoiselle from Agincourt, parlez-vous

You're the girl we all adore,

Show us the way to win the war.

Inky-pinky parlez-vous.

Typical of them in some ways, very untypical in others, was the war poet Wilfred Owen seen here, (pic 5).

Picture 5

Owen's poems, which we'll hear at a later Society evening, pretty much foretold his own death in the trenches, just a week before the Armistice. A similar ominous note echoes through our next song, about a young lieutenant taking his leave of all he holds dear. Superficially the song sounds like a bouncy, jolly music hall item, typical of the era, with all the cocktail slang of the smart set. But underlying this is the poignant sadness of a likely final parting, vividly expressed by some of Bertie's 'pathetic' parting words - 'tickled to DEATH to go', 'Bonsoir' meaning Good Night - and 'Napoo' - an army slang word of the time for 'no more', 'all over', 'finished and klaar', as we would say.

Brother Bertie went away

To do his bit the other day

With a smile on his lips

and his Lieutenant's pips

upon his shoulder bright and gay.

As the train moved out he said,

'Remember me to all the birds.'

And he wagged his paw

and went away to war

shouting out these pathetic words:

Goodbye-ee, goodbye-ee,

Wipe the tear, baby dear, from your eye-ee

Tho' it's hard to part I know,

I'll be tickled to death to go.

Don't cry-ee, don't sigh-ee,

there's a silver lining in the sky-ee

Bonsoir, old thing, cheerio, chin, chin,

Nap-poo, toodle-oo, Goodbye-ee.

Picture 6

The new recruit had to remember, as Vera Lynn would remind Mr Jones in the next war, that the bugler was not a civilian bandsman. The impulse to take out your irritation on the bugler was well captured by Irving Berlin in a 1918 hit that remained popular in the next war.

Oh how I hate to get up in the morning

Oh how I'd love to remain in bed;

For the hardest blow of all, is to hear the bugler's call

You've got to get up,you've got to get up

You've got to get up in the morning!

Some day I'm going to murder the bugler,

Some day they're going to find him dead;

I'll amputate his reveille, and step upon it heavily,

And spend the rest of my life in bed. (X2)

And then I'll get that other pup,

The one that wakes the bugler up

And spend the rest of my life in bed!

Picture 7

Despite the army's best efforts to suppress this song as insubordinate and bad for morale, it was often sung by troops on the march to the front line and this possible fate.

If you want to find the general, I know where he is,

I know where he is,

I know where he is,

If you want to find the general, I know where he is,

He's pinning another medal on his chest

I saw him, I saw him,

Pinning another medal on his chest

Pinning another medal on his chest

If you want to find the sergeant, I know where he is,

I know where he is,

I know where he is,

If you want to find the sergeant, I know where he is,

He's drinking all the company rum

I saw him, I saw him,

Drinking all the company rum

Drinking all the company rum

If you want to find the private, I know where he is,

I know where he is,

I know where he is,

If you want to find the private, I know where he is,

He's hanging on the old barbed wire

I saw him, I saw him,

Hanging on the old barbed wire

Hanging on the old barbed wire

Pack up your troubles in your old kit-bag

and smile, smile, smile.

While you've a lucifer to light your fag,

Smile, boys, that's the style.

What's the use of worrying?

It never was worthwhile, so

Pack up your troubles in your old kit-bag

and smile, smile, smile. (X2)

Picture 8

The Spitfire is carrying not bombs but two kegs of beer under its wings, which no doubt were well chilled by the time it landed.

Here's to good old beer, drink it down, drink it down,

Here's to good old beer, drink it down,

Here's to good old beer, it makes you feel so queer,

Here's to good old beer, drink it down!

Rolling home, rolling home, rolling home, rolling home,

By the light of the silvery moo-oo-oo-oon,

Happy is the day when the soldier gets his pay,

And we go rolling, rolling home!

Here's to good old whisky, drink it down, drink it down,

Here's to good old whisky, drink it down,

Here's to good old whisky, it makes you feel so frisky,

Here's to good old whisky, drink it down!

Rolling home, rolling home, rolling home, rolling home,

By the light of the silvery moo-oo-oo-oon,

Happy is the day when the soldier gets his pay,

And we go rolling, rolling home!

Rolling home.

There's a long, long trail a-winding

Into the land of my dreams,

Where the nightingales are singing

And a white moon beams.

There's a long, long night of waiting

Until my dreams all come true;

Till the day when I'll be going down

That long, long trail with you.

In very similar sentimental vein is our next song, an exhortation to those left behind to keep the soldier's home ready for his longed-for return.

Keep the home fires burning

While your hearts are yearning,

Though the lads are far away,

They dream of home.

There's a silver lining,

Through the dark clouds shining,

Turn teh dark clouds inside out,

Till the boys come home.

Picture 9

Our next song was written in America in 1917, so it clearly relates to the Great War. The sombre final verse reflects a real-life experience that was all too common, and we'll sing it in an appropriately more solemn way.

Around her hair she wears a yellow ribbon

She wears it in the springtime

In the merry month of May

And if you ask her why the heck she wears it

She wears it for a soldier who is far, far away

Far away, far away

She wears it for a soldier who is far, far away.

Around the park she wheels a perambulator

She wheels it in the springtime

In the merry month of May

And if you ask her why the heck she wheels it

She wheels it for a soldier who is far, far away

Far away, far away

She wheels it for a soldier who is far, far away.

Behind the door her father keeps a shotgun

He keeps it in the springtime

In the merry month of May

And if you ask him why the heck he keeps it

He keeps it for a soldier who is far, far away

Far away, far away

He keeps it for a soldier who is far, far away.

Now on his grave she lays a wreath of roses

She lays it in the springtime

In the merry month of May

And if you ask her why the heck she lays it

She lays it for a soldier who is far, far away

Far away, far away

She lays it for a soldier who is far, far away.

When at last this war is over, no more soldiering for me,

When I get my civvy clothes on, oh how happy I shall be;

No more standing to attention, no more eating from a tin,

I will tell the sergeant-major what I've always thought of him!

Bless 'em all, bless 'em all

The long and the short and the tall

Bless all those Sergeants and WO1's,

Bless all those Corporals and their bleedin' sons,

Cos we're saying goodbye to 'em all.

And back to their billets they crawl,

You'll get no promotion this side of the ocean,

So cheer up my lads, bless 'em all.

Jack Dunn, son of a gun, over in France today,

Keeps fit doing his bit up to his eyes in clay.

Each night after a fight to pass the time along,

He's got a little gramophone that plays this song:

Take me back to dear old Blighty!

Put me on the train for London town!

Take me over there,

Drop me ANYWHERE,

Liverpool, Leeds or Birmingham, well, I don't care!

I should love to see my best girl,

Cuddling up again we soon should be,

Tiddley iddley ighty

Hurry me home to Blighty

Blighty is the place for me!

Take me back to our own Union

Put me on the ship for Simon's Town

Take me over there,

Drop me ANYWHERE,

Pretoria, Paarl or Pofadder, well, I don't care!

Ek varlang so na my meisie

Ons sal nog die rusbank warm vry

Roll on the reunion,

Hurry me to the Union

The Union is the place for me!

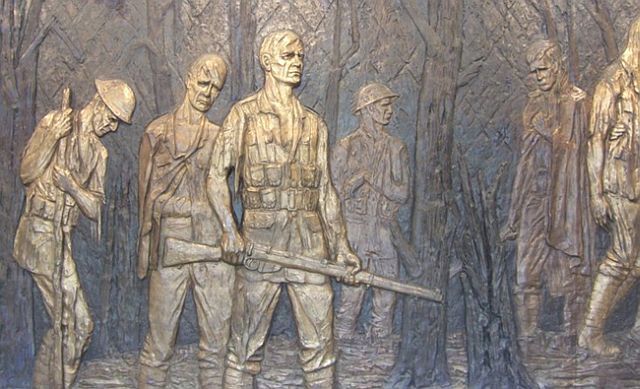

South Africans suffered as much as anybody else in the Great War. This is hauntingly reflected by this panel from the Delville Wood memorial (pic 10) depicting the battered remnant of the 1st SAI Brigade as they leave that forest of hell.

Picture 10

It's said that some of our countrymen, even at that lowest of low points, found the spirit and strength to sing our most beloved ballad of love in the midst of war. Partly in tribute to them, we'll finish with that timeless tribute to the girl that the South African soldier has left behind. Please allow Dave to play his instrumental interlude where it's indicated.

My Sarie Marais is so ver van my hart,

Maar'k hoop om haar weer to sien.

Sy het in die wyk van die Mooirivier gewoon,

Nog voor die oorlog het begin.

O bring my t'rug na die ou Transvaal

Daar waar my Sarie woon.

Daar onder in die mielies

By die groen doringboom,

Daar woon my Sarie Marais.

Return to Society's Home page