The South African

The South African

by Robin Smith ©

Address to SAMHS Jhb branch on 13 March 2008At Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee and around the little wooden Methodist church named Shiloh Meeting House on 6th and 7th April 1862, was fought the first major battle in the western theatre of the civil war. It was one battle that the Confederacy simply had to win in order to restore the Confederate frontier to the Kentucky-Ohio border. The casualty totals were shocking and plunged both North and South into outrage. Each side lost roughly 1700 killed and 8000 wounded. A Confederate soldier-novelist, George Washington Cable, later said, "The South never smiled again after Shiloh."

Map of the North West

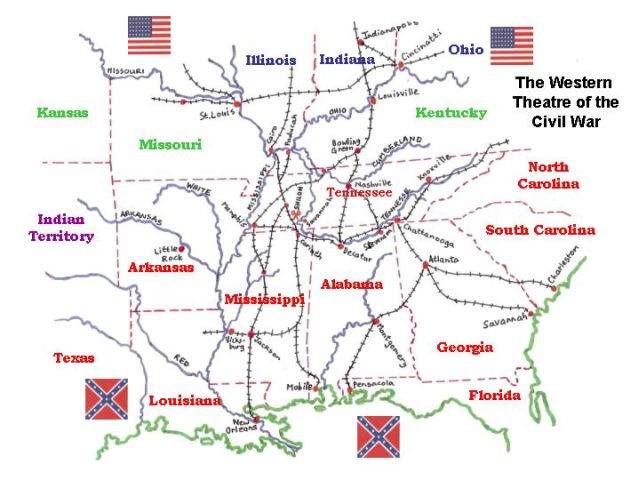

By 1860 the eight western states of the north were becoming the heartland of America. Their population growth had been explosive in the last 30 years. The border states of Kentucky, Missouri and Kansas were of dubious loyalty but the rest were strongly opposed to the rebellion and secession of the Southern states. The principal highway for the huge surpluses of meat and grain from the Midwestern states was the Mississippi River. Union strategy in the west was aimed at maintaining control of the 'Father of Waters', as President Lincoln referred to this mighty waterway.

OHIO INDIANA ILLINOIS MICHIGAN WISCONSIN IOWA MISSOURI MINNESOTA

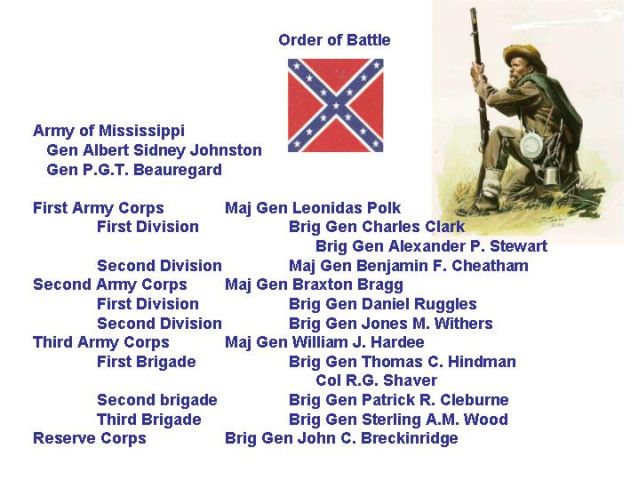

At the start of the war Kentucky's desire to remain neutral was respected by both sides. General Albert Sidney Johnston, believed to be a man of great strategic ability was put in command of the Western theatre by Confederate President Jefferson F. Davis. They were close friends. Johnston had fought in the Texas Revolution in 1836 and with great gallantry in Mexico. In 1858 he lead the Utah expedition to suppress the Mormon rebellion. He was esteemed by many but resigned from the Union army the day his adopted state of Texas joined the rebellion and was now the highest ranked field officer in the Confederate army.

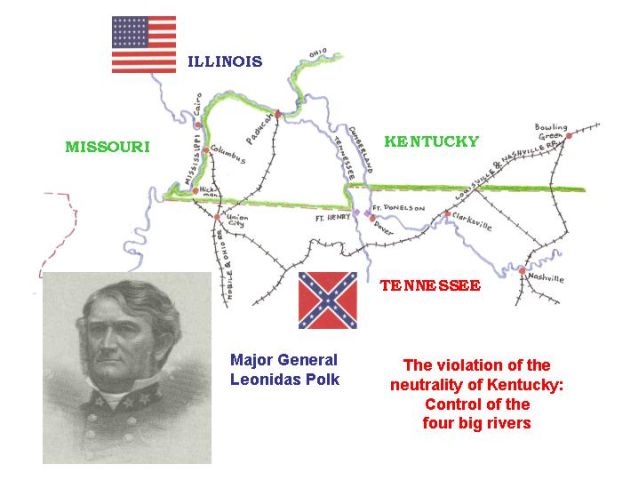

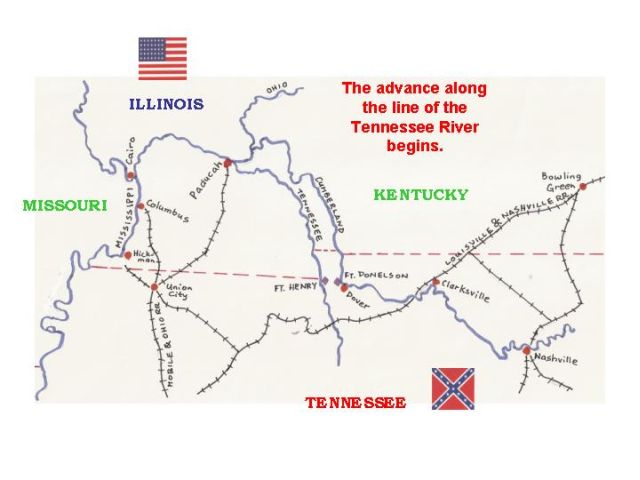

Major General Leonidas Polk occupied Columbus, Kentucky a few days before Johnston arrived in Nashville, Tennessee to take command. Polk, another intimate of Jefferson Davis, had been trained at West Point but had left the army and become Episcopalian Bishop of Louisiana. His advance on Columbus was predicated on a reported Federal move from Cairo, Illinois. Now given reason to advance into Kentucky, the Federals occupied Paducah at the confluence of the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers and the neutrality of Kentucky was a thing of the past.

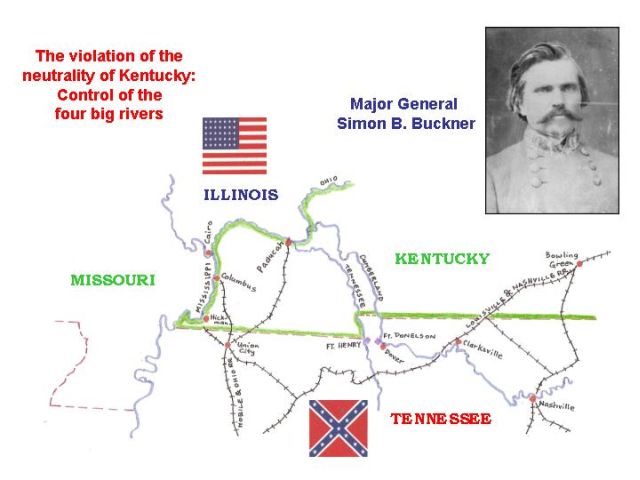

Kentuckian Brigadier General Simon B. Buckner was a West Pointer who had fought with distinction in the Mexican war. Only when his native Kentucky was invaded by both protagonists did Johnston persuade him to accept a Confederate commission. Buckner and five thousand troops were sent to hold Bowling Green, Kentucky an important railroad junction.

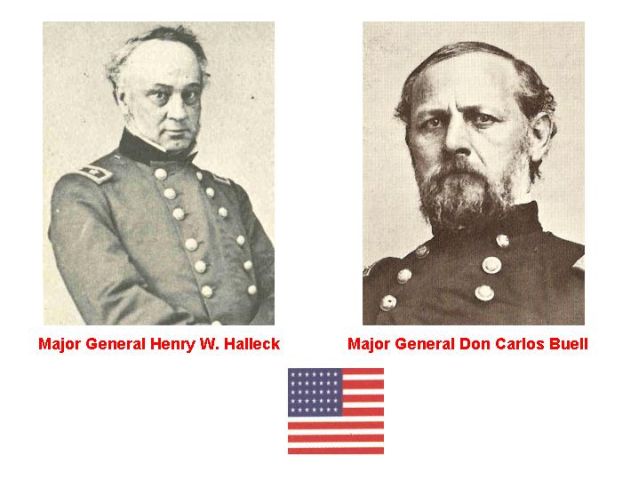

In November 1861 Major General Henry W. Halleck was appointed commander of the Department of the Missouri. Halleck was a strange character. A West Pointer who had left the army in California in the 1850's to practice law, he had translated military texts and written books on strategy. Known as "Old Brains" he was considered a highly intellectual soldier. He had a good understanding of the political pressures that must bear on any general and he was a solid, conscientious and very capable administrator. What he knew about war came out of books but he was considered by many to be the foremost exponent of the art of war in America.

Tasked by President Lincoln with a move into East Tennessee whose population was sympathetic to the Union was Major General Don Carlos Buell. Austere, methodical and intellectual, he did not consider a move through the rugged mountains to be feasible. Neither would he advance on Bowling Green despite pressure from Halleck.

The commander in Cairo, Illinois was an obscure Brigadier General by the name of Ulysses S. Grant.

Fort Henry and Fort Donelson

Once the Confederates had violated Kentucky's neutrality Grant was not slow to occupy Paducah, Kentucky at the confluence of the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers and on 2nd February 1862 he initiated an advance down the Tennessee River. West of Bowling Green was[sic] two forts which were the keys to the defence of the entire region, Fort Henry on the Tennessee and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. The threat to these vital positions caused Johnston to reinforce both forts and Buckner's men evacuated Bowling Green and were sent to Fort Donelson. Fort Henry was flooded by the high water in the Tennessee River and quickly surrendered to the gunboats of the U.S Navy.

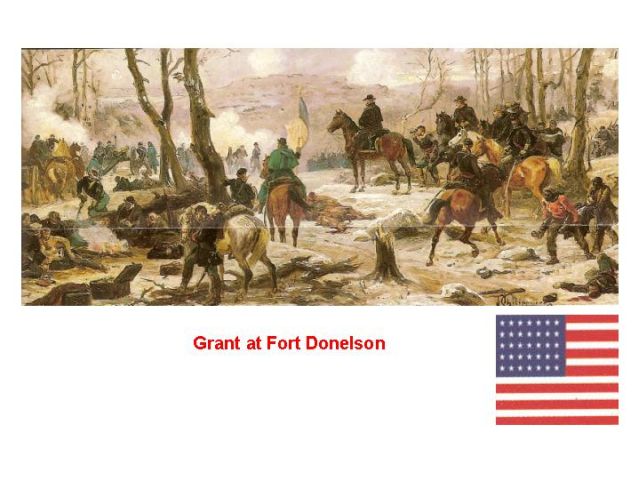

Grant at Fort Donelson

At Fort Donelson the navy's gunboats were initially repulsed by the Confederate heavy gun batteries. At one time the Confederates looked like opening an escape route to Nashville but then retreated back into their lines as snow and sleet had begun to fall. Grant ordered Brigadier General C.F. Smith to attack on the left while Brigadier Generals Lew Wallace's and John McClernand's divisions regained their earlier positions. Smith's attack was a success and his men occupied the Confederate lines ready for a further assault at dawn the next day, 16th February.

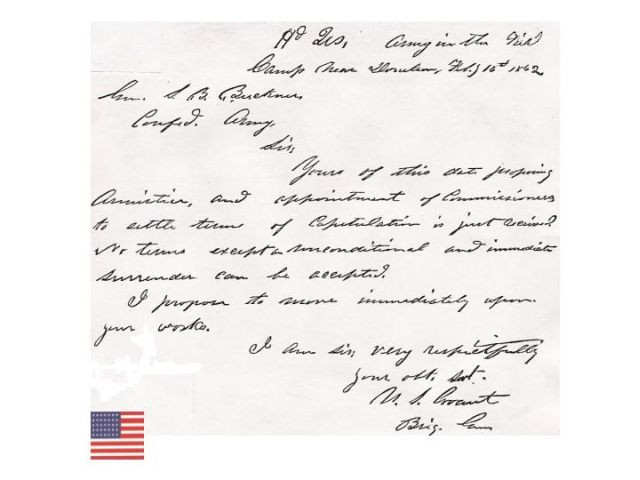

Unconditional surrender letter

With the Confederates surrounded, Brigadier General Simon Buckner sent a letter through the lines with a flag of truce. Buckner, a friend of Grant's from the old army when they were both stationed in California, asked for an armistice and the appointment of commissioners to settle terms of surrender. Grant's reply was unequivocal: "No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works." Buckner had no choice but to accept "the ungenerous and unchivalrous terms which you propose."

Grant's first task was to send back word of his victory and without delay he got off a message to Halleck in St. Louis:

Grant as Major General

Halleck had been planning to demote Grant but now President Lincoln sent Grant's name to the Senate for promotion to Major General which was promptly confirmed. Suddenly Grant was famous. He was a man who knew how to win battles and his "unconditional and immediate surrender" led men who had never heard of Grant before to tell one another that his initials stood for "Unconditional Surrender." This was the North's first substantial victory and the Tennessee River was now opened as a highway to the south. The Confederates could do nothing but retreat.

General Albert Sidney Johnston in Nashville had been awakened before dawn to be told of the surrender of Fort Donelson. He ordered the city to be evacuated and President Jefferson Davis was hard-pressed to ward off calls for his dismissal. On 23rd February, his army reduced to only fourteen thousand men, he marched southwards determined to reach Corinth, Mississippi and mount an all-out campaign to defend the Mississippi valley.

While the battle at Fort Donelson was in progress, Buell was marching laboriously towards Nashville from Bowling Green. He ordered Brigadier General William Nelson's division to be sent by steamer up the Cumberland River.

William "Bull" Nelson, six feet four inches tall and three hundred pounds was a towering bull of a man. A naval officer from Kentucky, on the outbreak of war he was commissioned a Brigadier General in command of a division. Arriving at Fort Donelson on 24th February, Grant sent the men on to Nashville instructing Nelson to report to Buell when he arrived there. Buell, arriving north of the river was indignant when he found a division of his own army in Nashville ahead of him.

Possibly exceeding his orders, Grant went to Nashville and had an icy meeting with Buell. Halleck was in the dark about all this as the communication system had broken down although neither he nor Grant had realized it. Messages were sent by boat to Paducah and then by telegraph to St Louis. The civilian operator in Paducah was a Confederate sympathizer who indulged in sabotage by neglecting to send on the messages. Halleck was surprised to learn that Grant had been to Nashville and that C.F. Smith's division had been ordered there to allay Buell's somewhat irrational fears of a Confederate attack.

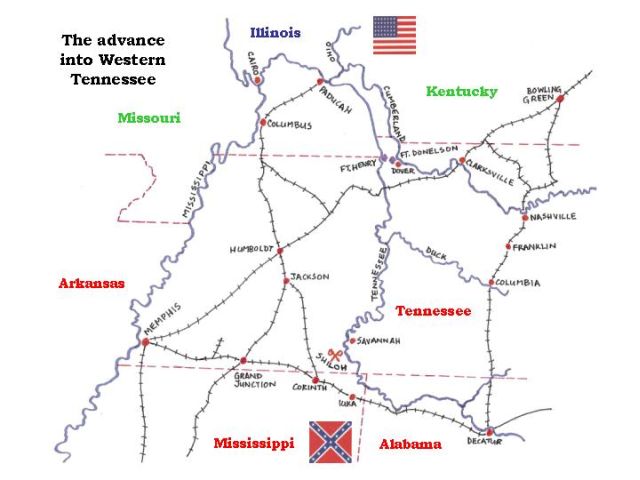

Advance into Western Tennessee

Halleck's telegram to Grant read: "Why do you not obey my orders to report strength and positions of your command?" and Grant knew he was in trouble. He responded: "I am not aware of ever having disobeyed any order from headquarters" and gave an outline of the forces under him. The matter might have ended there but Halleck was determined to stand Grant in the corner for a while which unfortunately served as a brake on action at a time when speedy Federal movement down the Tennessee Valley was of great importance. Halleck's orders were for Major General C.F. Smith to command an expedition down the Tennessee River to attack Rebel railroad bridges near Eastport, Mississippi and railroad connections at Corinth, Mississippi and Jackson and Humboldt, Tennessee. Grant was to remain at Fort Henry. The War Department in Washington now intervened in the person of the President himself - Lincoln was in no mood to see the victor of Fort Donelson dropped without a fair hearing. Halleck backed down realizing that he must either file formal charges or drop the whole subject and he reported to Washington that "the whole unpleasantness had been a regrettable misunderstanding."

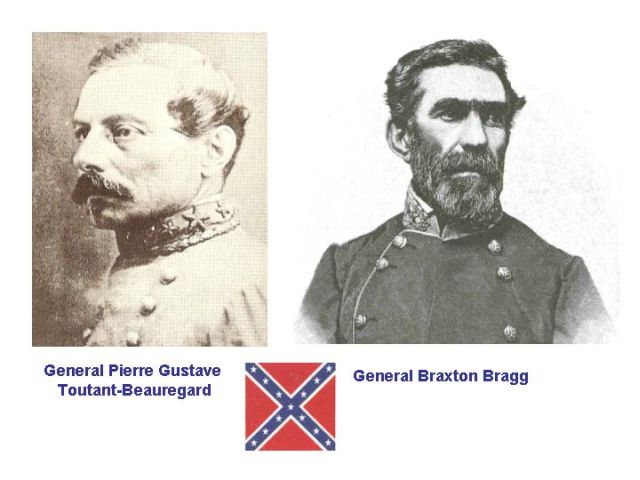

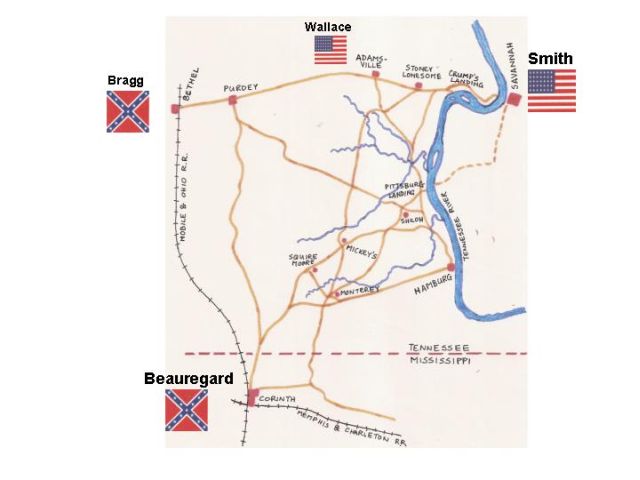

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, a national hero in the South, and now a full General had directed the operations at Fort Sumter in Charleston harbour, which ignited the civil war, and much of the fighting at Manassas in July 1861. His name now a household byword, he was sent to the west in February 1862. Johnston ordered him to Corinth with authority to act independently in the Mississippi Valley. Meeting with Bishop Polk at Jackson, Tennessee, he insisted on the evacuation of Columbus, Kentucky over Polk's objections. Beauregard sent letters to the governors of Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama asking for recruits and planned, he said, to "threaten if not indeed take St Louis itself." The Confederacy's eighth ranked General, Braxton Bragg hurried north and arrived in Jackson, Tennessee on 2nd March ahead of his well-drilled command of ten regiments, nearly ten thousand fresh soldiers. Brigadier General Daniel Ruggles arrived in Corinth with a Louisiana brigade the day after the surrender of Fort Donelson.

Major General Charles F. Smith was an officer of the regular army who had been commandant of cadets at West Point when Grant was there. Many men, writing about Smith, said he was the finest-looking soldier they ever saw and Grant confessed that he never felt quite right issuing orders to him.

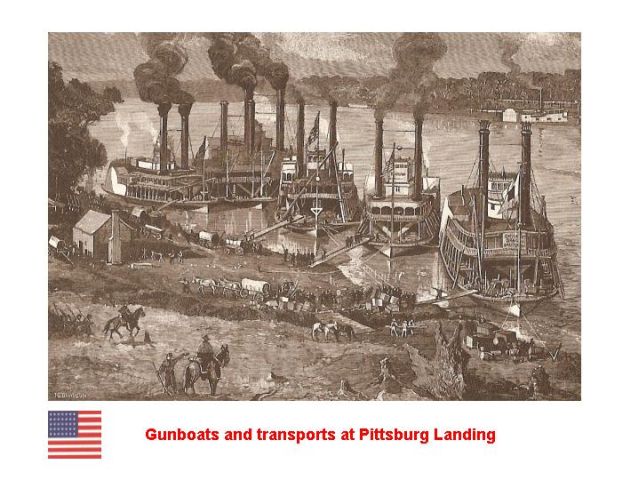

Smith's army arrived in Savannah, Tennessee in a long, winding column of sixty-three transports with flags flying and the regimental bands playing.

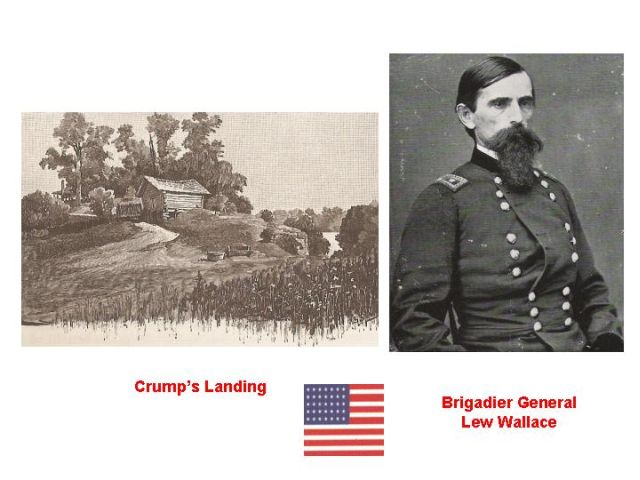

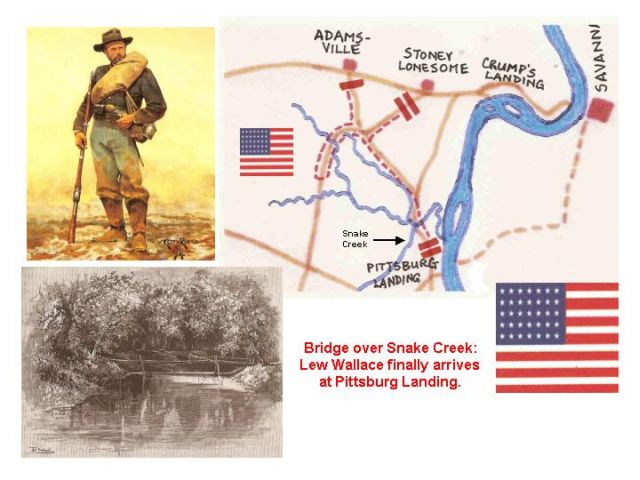

Brigadier General Lew Wallace was landed at Crump's Landing a few miles upstream from Savannah with a full division and orders to damage the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. Late in the evening of 12th March Smith was rowed across the river to give Wallace his orders. After the conference he stepped aboard his small boat, slipped and fell, skinning his leg from ankle to knee against the edge of a seat. Infection developed and the leg was so swollen and painful that Smith was soon confined to bed.

Wallace's situation - map

Wallace advanced inland and Major Hayes's 5th Ohio Cavalry damaged a bridge and a section of line of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad near Bethel, Tennessee.

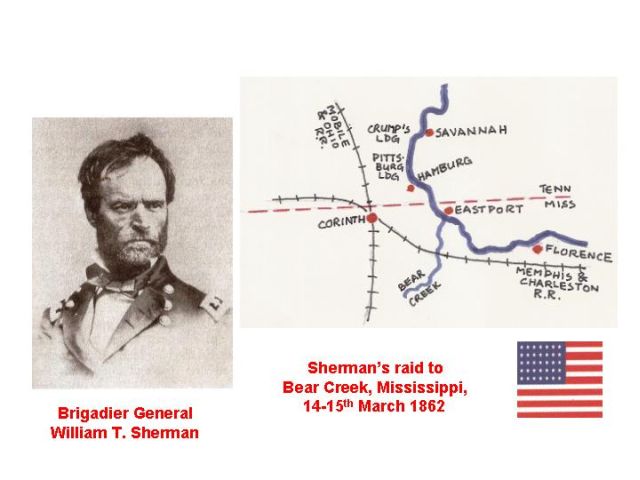

Brigadier General William T. Sherman had been in command at Paducah but now had a newly-created division of mostly Ohio regiments. The second part of Smith's plan was for Sherman to proceed thirty miles upriver from Savannah to the mouth of Bear Creek in northern Mississippi. From there Sherman's cavalry would strike overland at the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. The rain was falling in torrents and the river was rising six inches an hour. More than four miles inland Sherman's men could proceed no further, their way barred by a flooded stream. On their return to the gunboats what had been an ankle deep slough was now a lake, waist deep and a half-mile wide. The guns bogged down and the horses' harnesses had to be cut to save them. The guns were dismantled and removed piece by piece using rowing boats and a pontoon bridge had to be constructed to re-embark the force. The mighty Tennessee was proving to be a formidable obstacle and Sherman cruised downriver to the first landing site above water - Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee.

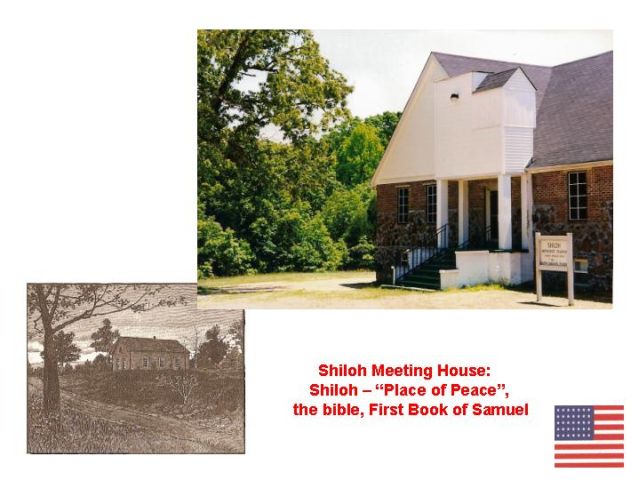

Shiloh Methodist church

Halleck's instructions were not to bring on an engagement and Sherman considered that an advance on Corinth from Pittsburg Landing could be done in accordance with these orders. Reinforcements were sent from Savannah and Sherman set up his headquarters two miles from the landing near a one-room, log-hewn church, named Shiloh Meeting House by a small group of Southern Methodists. Shiloh - "A place of Peace" from the bible, First Book of Samuel.

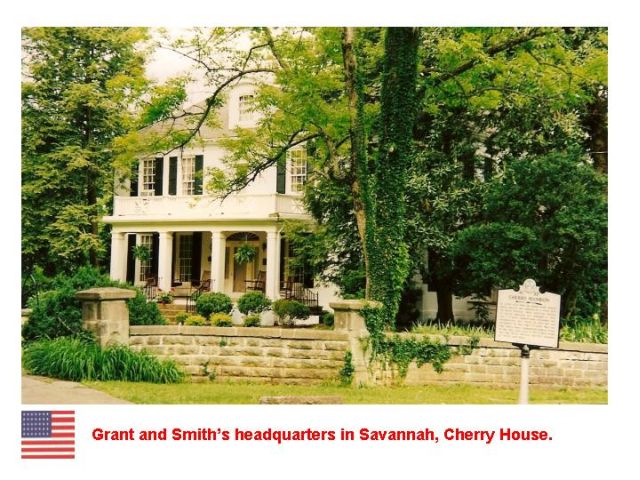

Grant's suspension now lifted, he arrived in Savannah on 17th March. Army headquarters was in a fine mansion overlooking the Tennessee River. It was owned by William H. Cherry, a man of substance who owned several thousand acres of farmland and a good-sized collection of slaves but was stoutly Unionist in his sympathies. In an upstairs bedroom was C.F. Smith whose infected leg stubbornly refused to heal.

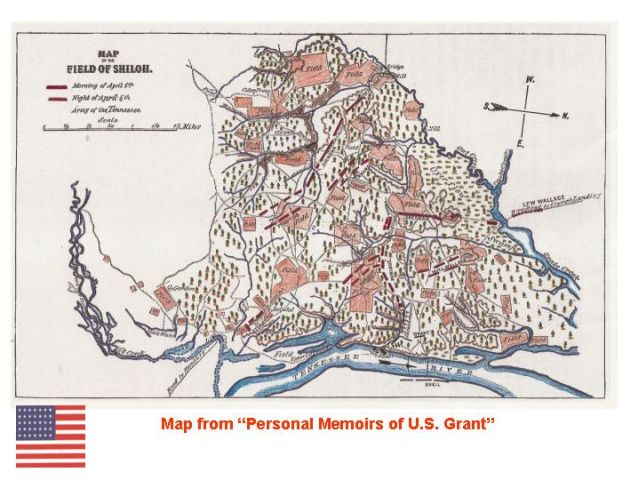

Grant had relied on the judgment of Smith and Sherman in ordering the concentration at Pittsburg Landing, Grant told Sherman that the troops moving up from Savannah should "report to you" but on 19th March he steamed up river to inspect personally the encampments at Crump's and Pittsburg Landings. The triangle of land between the Snake and Lick Creeks allowed ample room to encamp many thousands. It was a good position to defend and ideal as a base for an attack on Corinth, twenty-three miles to the south. Grant was well satisfied with what he saw and was ready to advance once Buell's men arrived as Halleck's orders required.

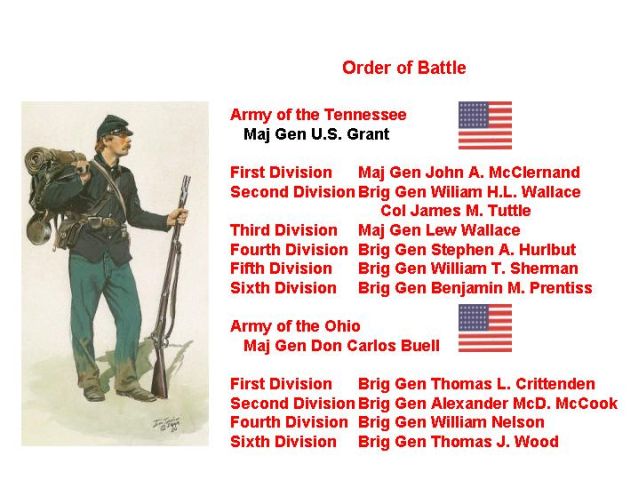

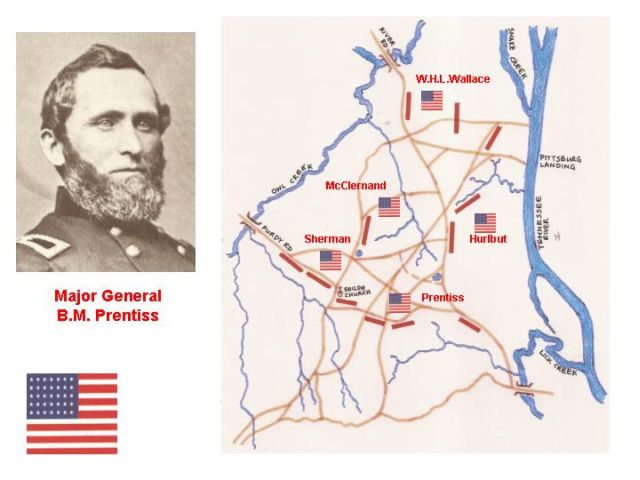

By early April Grant had six divisions in place. At Pittsburg Landing were Sherman, John McClernand, Stephen Hurlbut, Benjamin M. Prentiss and William H.L. Wallace with Lew Wallace at Crump's Landing. There were thus thirty-seven thousand soldiers at Pittsburg Landing with seven thousand five hundred more at Crump's Landing. Buell's army was slowly closing on Savannah with thirty thousand more.

Sherman led several strong patrols on land and on the river. On one occasion a lone Arkansas ranger was brought into camp leading a fine sorrel mare. The man claimed his Union captor had tricked him and implored Sherman not to take his horse. Sherman responded that the horse was captured property. "But it is a racehorse" the man protested. "All the better," remarked Sherman who appropriated the steed for his own use. It was one of the few good things that happened to Sherman at Shiloh.

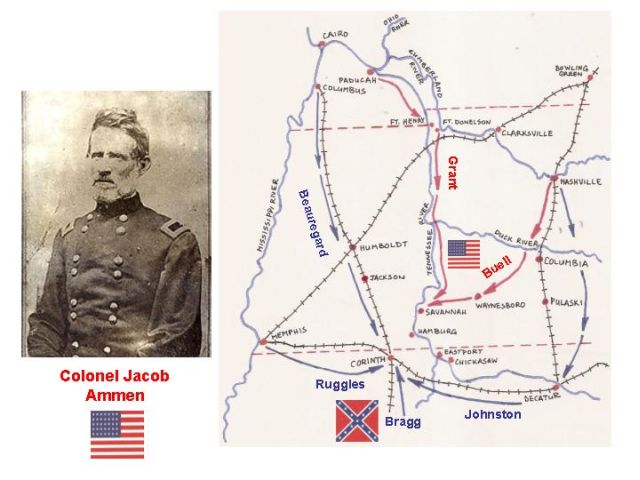

Major General Don Carlos Buell was marching overland from Nashville to Savannah. Halleck's orders to Buell were that he should move all available forces by river up the Tennessee. Buell typically balked at this and amazingly Halleck agreed to his march of 122 miles over rugged country with tortuous, muddy roads and several deeply flooded rivers to cross. They broke camp at Nashville on 16th March and reached Columbia, Tennessee to find that Confederate cavalry had destroyed all the bridges over the Duck River. Buell only left Nashville on the 25th, Halleck using the good telegraph connection from St Louis to prod him into action. William Nelson became frustrated by the slow progress with the bridge building and on 27th March obtained Buell's permission to attempt a crossing of the river. One of his brigade commanders, Colonel Jacob Ammen found a ford that ran the depth of an army wagon. Nelson's instructions were unique: "The men will strip off their pantaloons and secure their cartridge boxes around their necks. Bayonets will be fixed and the pantaloons carried in a neat roll on the point of the bayonet. A halt will be ordered on the far side to allow the men to take off their drawers, wring them dry, and resume their clothing." At six in the morning of 29th March the nearly naked Fourth Division made it across without difficulty and by 2nd April the final division was across. It had taken Buell's army exactly two weeks to cross a river two hundred yards wide.

Albert Sidney Johnston crossed the Tennessee at Decatur, Alabama and on 22nd March his army was united with Beauregard around Corinth. When he left Nashville he had perhaps 17000 and Polk had 23000 more in the area of Columbus, Kentucky. Five thousand had been sent from Mobile, Alabama and Bragg's ten thousand had been a welcome addition. He now had between forty and forty-five thousand men in and around Corinth. Johnston was now in a position to mount an offensive with an army that had only recently been considered too weak and dispirited to do anything other than await destruction.

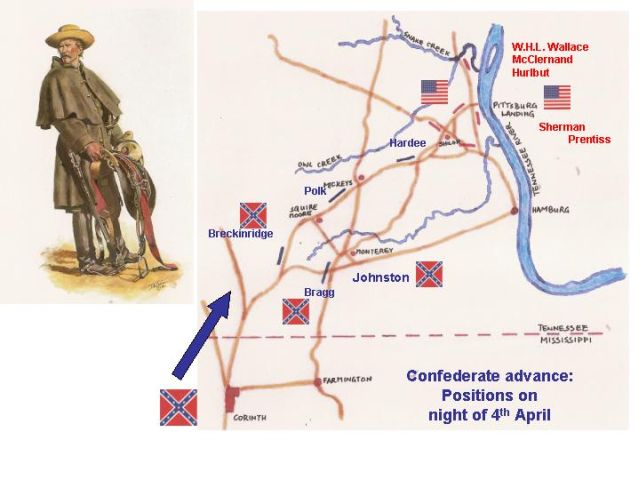

Johnston had anticipated an attack in the Pittsburg Landing area for some days and, after a meeting late at night on 2nd April with Braxton Bragg, determined to advance northwards out of Corinth. Preparations were ordered for an immediate advance and corps commanders Bragg, Polk, Breckinridge and Hardee were ordered to have their "commands in hand ready to advance" by 6 a.m. on 3rd April. The narrow streets of Corinth were jammed and with rain falling gently the muddy roads caused unforeseen delays. Beauregard's plan was in essence a large-scale raid and envisioned that Grant would be beaten back to his transports and the river. The Confederates would then remove all the captured equipment to Corinth, the strategic point of the campaign.

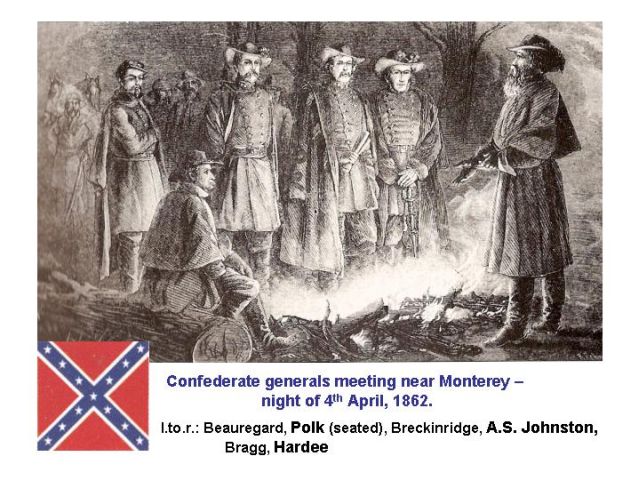

On the night of 4th April the Confederate troops were woefully dispersed and well behind schedule. Hardee's corps led the advance and was along the Corinth-Pittsburg Road about three miles from Shiloh Church. Polk was behind him on the same road within a few miles of Mickey's and Bragg lay along the Monterey-Pittsburg Road. Johnston was at Monterey and during the afternoon and evening conferred with his generals and issued instructions for a full-scale attack early the following morning. By 7 a.m. on 5th April the army was to be fully deployed and an hour later the attack was to begin.

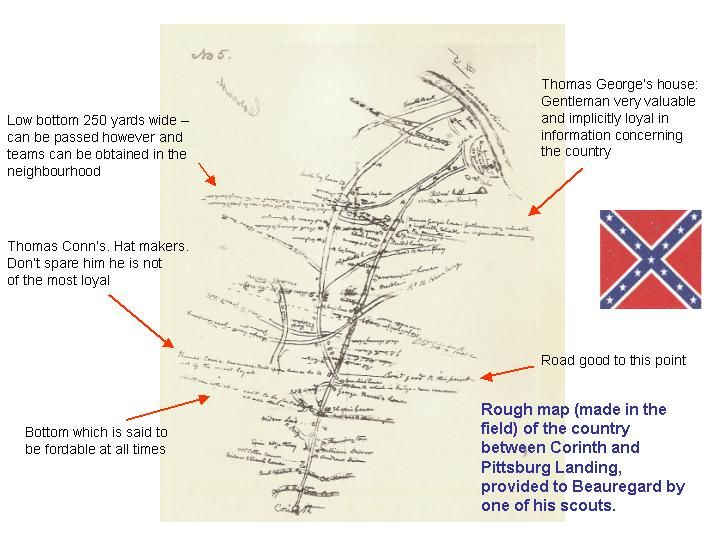

Map by Beauregard scouts

That night the rain fell in torrents and Johnston's army, exposed on open ground without tents, was drenched. Although Hardee put his men in line of battle only two miles from Shiloh Church by 10 a.m., Bragg's, Polk's and Breckinridge's Reserve Corps were floundering in the mud and only reached their allotted positions towards evening. Unbelievably, Bragg and Beauregard felt that the army should retreat back to Corinth without a battle, but when Johnston rode up he said quietly but firmly: "Gentlemen, we shall attack at dawn tomorrow."

That night the plans for the morning's battle were reviewed by the ranking Confederate generals. Colonel Thomas Jordan, using Beauregard's notes and "Napoleon's order for the Battle of Waterloo" drew up the army's marching orders. This concept called for an attack by succeeding waves of infantry with each corps aligned one behind the other across the entire front. It was fatally flawed as a plan as events would bear out. There was much concern among ranking officers that the advance from Corinth had been discovered by the enemy. At 7 a.m. on the 5th April Union pickets were driven from Widow Howell's house less than a mile from the Union camps. A Federal surgeon was captured by Hardee's pickets that evening who told them that Grant had returned to Savannah for the night - surely not the act of a commander expecting to fight.

Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee had been Indian country only forty-five years previously. In the decade before the Civil War the bluff had become the site of a store and the home of one Pitts Tucker and his family. He was a trader in hard liquor and Pitts Tucker's landing was a mandatory stop for the many river craft passing by. Although Savannah was pro-Union, on the western bank of the river the Confederate sentiment was much stronger and the farmers in the vicinity of Pittsburg and Crump's Landings were a valuable Confederate source of information. Despite the fact that the protracted three-day march of the Confederates from Corinth must have been seen by many, only two spies in the employ of Lew Wallace warned of their approach. Wallace was skeptical, concerned that they might be double agents, but sent a report to Grant who sent a note to Sherman about a threatened enemy attack. Sherman's reply was negative.

Major General John McClernand was now present at Pittsburg Landing and as the ranking officer should have assumed command but Sherman continued to be the "informal" camp commander. Sherman had no spies and information from Rebel deserters was not thought to be reliable. The warm April sun continued to shine and sent spirits soaring, the only basis for complaint from the ranks being the monotony of camp life. Sherman was a strong advocate of drill and instruction and by his order there was daily drill and fatigue duty. On 5th April Colonel Jesse J. Appler of the 53rd Ohio was particularly nervous. Seeing a party of mounted men at the far end of a nearby field, he reported to Sherman that the enemy was in sight. For his pains he got the reply: "Take your damn regiment back to Ohio. There is no enemy nearer than Corinth!"

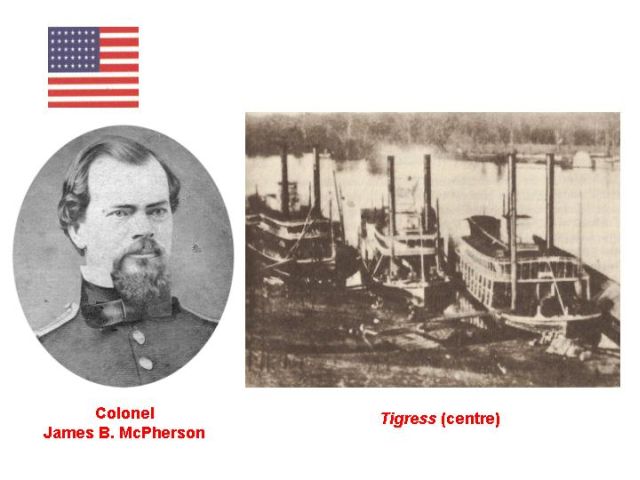

That night Grant hurried to Pittsburg Landing aboard his steamboat Tigress after a report that Major Ricker of the 5th Ohio Cavalry had run into a Confederate battle line. They had in fact encountered Hardee's corps drawn up with several batteries of artillery. Grant arrived as a storm raged and the night was so dark that he was unable to find his way along the muddy road to Shiloh Church. He met Major General W.H.L. Wallace and Colonel James McPherson of his staff returning from a visit to Sherman's headquarters. They reported everything quiet at the front and because of the storm they made their way back to the landing. Grant's mount slipped in the treacherous footing and fell heavily, pinning his leg. There was no fracture but his ankle became so swollen that his boot had to be cut off and he was unable to walk.

To Sherman's left was the division of Major General Benjamin M. Prentiss. He had been a captain in Mexico and now headed a division of recruits. Guard duty was light and drills were not a regular routine. Of his ten regiments, only one had ever been in battle.

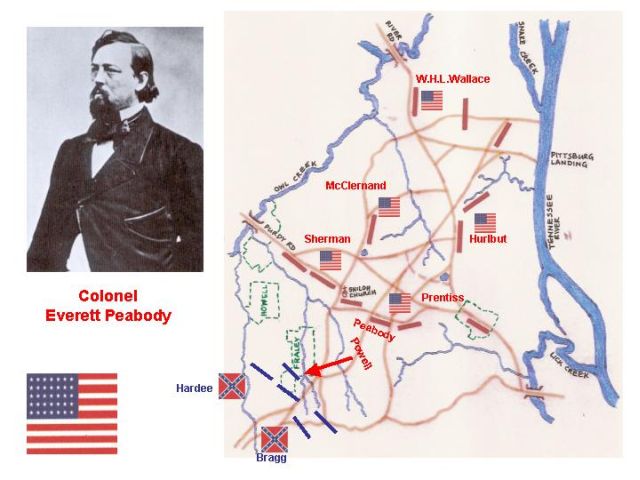

Colonel Everett Peabody had approached Prentiss with a suggestion that the division be put in condition to resist an attack but Prentiss "hooted" at the idea of an attack. Major James E. Powell of the 25th Missouri reported seeing long lines of camp fires that night. Peabody, upon his own responsibility, told Powell to take a patrol and reconnoitre in front of the army's pickets. This decisive action was responsible for saving the Union army from certain destruction. Powell took out three companies of the 25th Missouri at 3 a.m. on 6th April to look for the enemy. They filed down an old wagon trail and disappeared into the darkness for a rendezvous with destiny.

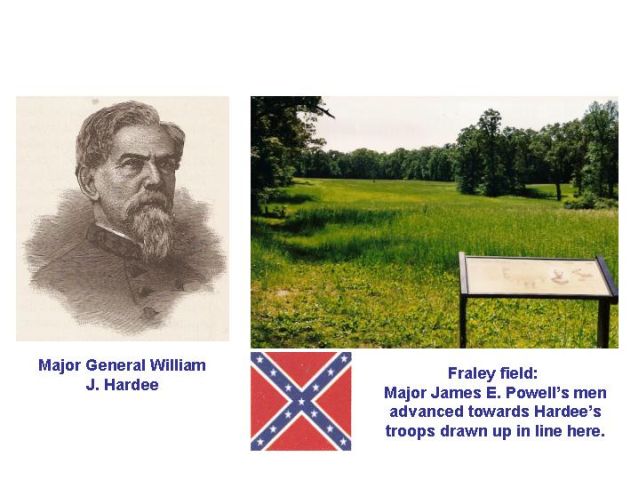

Major General William J. Hardee was a prominent general of the South and twice brevetted for gallantry in Mexico. He was tall and wiry and considered by Johnston to be his right arm. Hardee's men were the core of Johnston's Kentucky army, veterans of several months' service. They had waited in line the whole of the previous day while the other Confederate corps moved slowly into position and had camped where they stood. At dawn they were called into line and started to advance. Major Powell's men were drawn up in a long skirmish line on Fraley field and now witnessed the awesome sight of a seemingly endless line of grey infantry advancing towards them. It was shortly before 5 a.m.

At about 7.00 a.m. the rattle of musketry in the woods less than one thousand yards away alerted Everett Peabody to further trouble. With no orders from Prentiss, solely on his own authority he summoned the 25th Missouri's drummer and had the boy sound the long roll, the army's urgent call to arms. At 7.30 a.m. Peabody's men were looking to their front when suddenly the Confederates broke over the crest of the opposite ridge, seventy-five yards away. There was a flash of fire and a tremendous roar and the battle was at last a reality.

Prentiss's men were driven back as were Sherman's around Shiloh Church. Sherman was struck in the hand by a buckshot and his orderly, Private John Holliday, was shot and killed at his side.

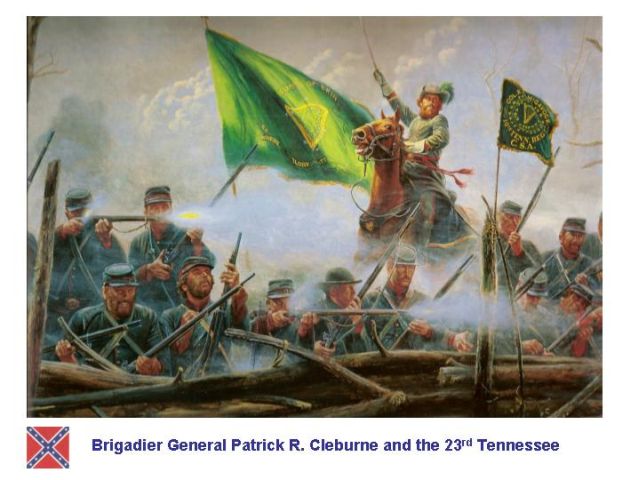

Hard-driving Arkansas Brigadier General Patrick Cleburne's men of the 23rd Tennessee attacked the 53rd Ohio of Colonel Jesse Appler whose nerves were at breaking point. Appler cried out "Retreat and save yourselves!" and the entire left flank of the 53rd Ohio ran to the rear. Cleburne was halted by artillery fire and by the fire of two other Ohio regiments. Things did not go well for the Confederates but Bragg's second line was approaching and the advance continued. Bragg later complained that it was impossible to maintain alignment and proper distance from Hardee's first line.

Sherman had ridden to the front at about 7 a.m. and sent staff officers to McClernand, Hurlbut and Prentiss to report that he had been attacked. Only when he saw the "glistening bayonets" of Bragg's second line at about 8 a.m. did he realize that "the enemy designed a determined attack on our whole camp." Sherman had been the victim of one of the greatest strategic surprises of the war. Twenty-one year old Lieutenant John T. Taylor saw Sherman astride his sorrel race mare cool and unperturbed. His conduct, said Taylor, "...instilled a feeling that it was grand to be there with him." He paid no attention to the bullets flying about and refused to panic when some of his troops fled their positions. In spite of the heavy undergrowth and swampy ground the Confederates were able to continue their advance and the Union army was now strung out in a loose uneven front, fighting desperately.

At Grant's headquarters in Savannah just as breakfast was announced the quiet of the spring morning was broken by the sound of cannon firing, in the vicinity of Pittsburg Landing. Within fifteen minutes General, staff, orderlies, clerks and horses were aboard Tigress and the steamer was moving upstream. He left orders for Nelson, who had arrived in Savannah the previous day, to move his command to the river opposite Pittsburg and for Buell to send his men to Pittsburg Landing. At 7.30 a.m. Grant's steamer closed in by the bank at Crump's Landing. Lew Wallace was waiting and Grant called out his instructions to have his division ready to move on receipt of orders. Wallace was an ambitious man, wanting to win fame as a soldier. What would happen in the next twenty-four hours would put military fame out of his reach.

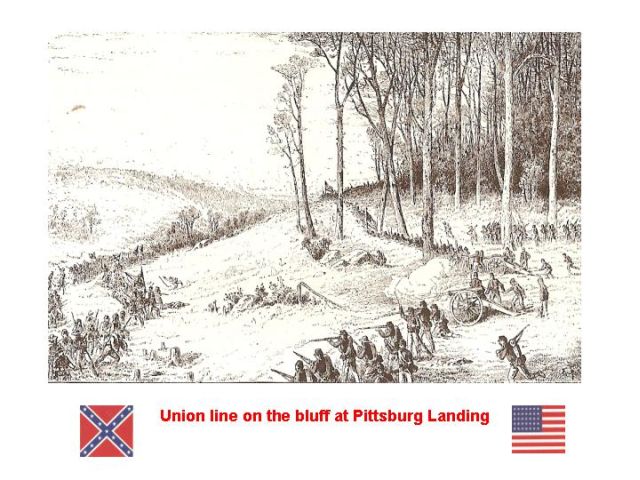

Tigress nosed into Pittsburg Landing at eight o'clock. Grant got on his horse to ride straight into the great battle of Shiloh. There was a dismaying crowd of stragglers, weaponless, panicky and disorganised, officers of rank among them. Grant put his staff to organizing an ammunition train and a staff officer was sent downstream on the Tigress with orders for Lew Wallace to bring up his division as fast as possible. His immediate task was to stave off disaster.

On the Federal right, Grant appeared and spoke to Sherman whose uniform was torn and rent with several bullet holes. A bloody handkerchief was wrapped tightly around his injured right hand. His sorrel mare had been killed so he took Lieutenant Taylor's mount and then this horse was killed too. He was mounted on a stray artillery horse when Grant arrived. This was the first time they had met face to face and Grant thought Sherman was doing well in stubbornly resisting the Confederate attack. He said that ammunition was on the way and Sherman was pleased with Grant's show of confidence.

Map - the hornet's nest

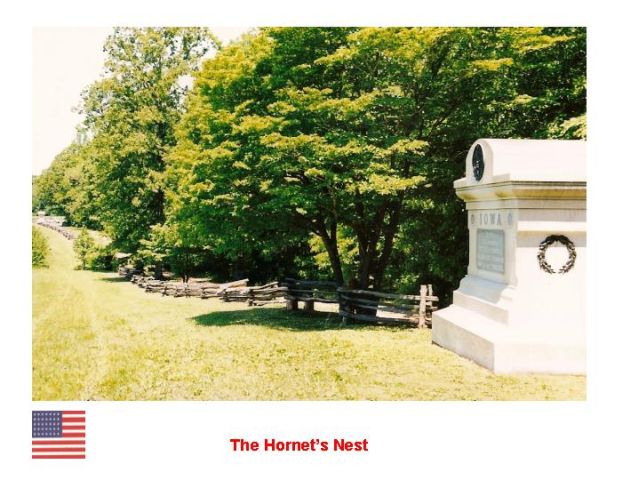

Grant galloped off to see Prentiss. Prentiss had been driven back into an eroded lane that ran parallel with the Confederate front where his raw troops were making a determined stand.

Grant told Prentiss to hold his ground at all hazards and this area was referred to as the hornet's nest. They held their position for five more hours.

As Grant and his cavalry escort rode past the 5th Ohio Battery, the battery commander, Captain Andrew Hickenlooper was amazed to see his father riding as one of the escort. He had joined an Ohio cavalry regiment to be able to be near his son and arrived unannounced at the Landing that morning. Grant set a strong guard on the bridge over the Owl Creek and sent a cavalry officer to ride to Crump's Landing to guide Lew Wallace to the field.

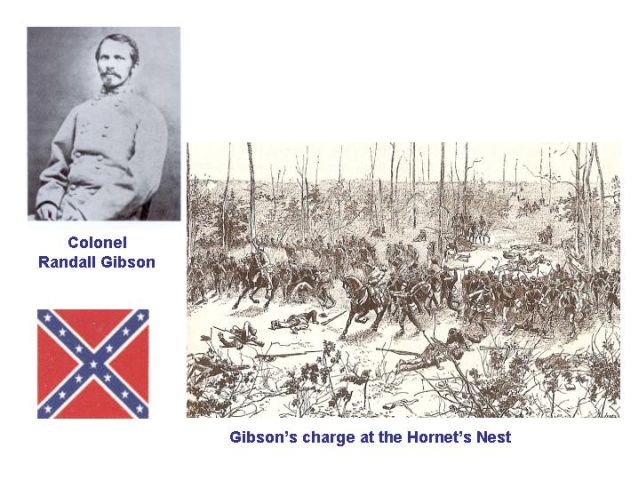

Braxton Bragg had already had two horses shot from under him and found Colonel Randall L. Gibson's brigade standing idle. Harsh words were exchanged and Gibson was ordered to charge the hornet's nest. They advanced through the thick underbrush into a virtual ambush. Try as they might Gibson's men could not stand up to the deadly fire from the sunken road. Bragg was known for his terrible disposition and could only bluster that Gibson was an arrant coward. A Confederate private saw so many men shot he thought he was in a slaughter house as Hickenlooper's guns fired double charges of canister into the advancing Confederates.

Johnston and his tin cup

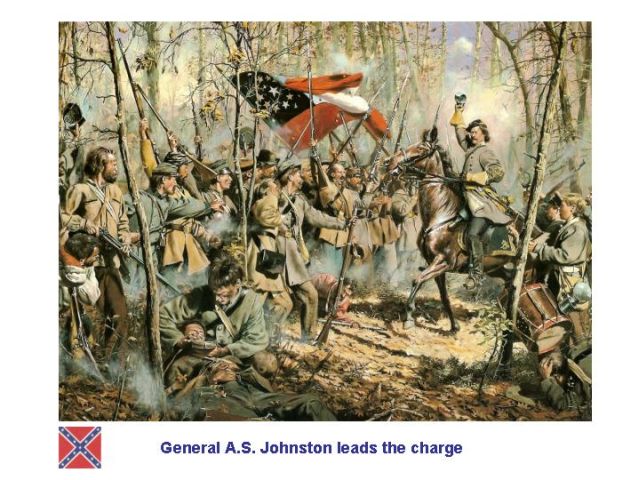

The Federal left along the river was held only by an isolated brigade of Sherman's division commanded by Colonel David Stuart and placed so as to guard a bridge over the Lick Creek. Johnston realized that if Stuart could be driven away then the Landing was not far distant. The ground was rough, heavily wooded and cut by ravines. Johnston had seen the initial Confederate advance slow when his men busied themselves in looting the captured Federal camps. Observing a Confederate officer emerge from a tent with an armful of trophies he sharply censured the man saying, "We are not here for plunder" and, picking up a little tin cup, said, "Let this be my share of the spoils today." A magnificent horseman and still holding the tin cup, Johnston urged his men to charge Brigadier General John MacArthur's 9th and 12th Illinois who had come to reinforce the hard-pressed Stuart. It was a few minutes before 2 p.m. and with a wild shout "which rose high above the din of battle" the Tennessee soldiers swept forward.

The charge was successful and much of the ground around a peach orchard was gained pushing the Federals back to a line at the rear of a pond.

During the battle, soldiers of both sides came here to drink and bathe their wounds. Both men and horses died in the pond, their blood staining the water dark red.

Johnston was elated and kicked up his left foot to show how a projectile had struck the edge of the sole of his boot. During the assault Johnston had been struck four times although only one had broken the skin. In the excitement of the aftermath of the charge, no one and perhaps not even Johnston, noticed the profusely bleeding wound behind the knee joint of his right leg. A Miniť ball fired from the rifled weapon of one of his own men at extreme range had torn the popliteal artery. Loss of blood caused him to collapse and fall from his horse. He was taken to shelter in a ravine close by but Colonel William Preston looked for a body wound thinking that he had a more serious injury than the one in his right leg. Soon the highest ranking American general ever to die on the battlefield lay dead at Preston's feet.

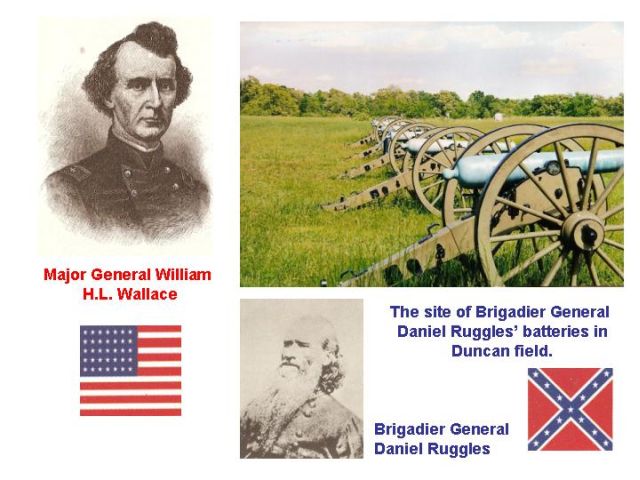

Clearly the Hornets' Nest would require more than the charge of massed infantry columns before it was taken. Brigadier General Daniel Ruggles, looking more like a patriarch than a general amassed the largest concentration of field artillery yet seen in the war. Sixty-two guns had an awesome effect and those Federals who could not escape to the rear surrendered. Prentiss was among them and it was now after 5 p.m. The Hornets' Nest had been overwhelmed but only after a dozen separate charges had been repulsed. Union Major General W.H.L. Wallace rose in his stirrups to observe the approaching enemy and was struck by a musket ball just behind the left ear. The gaping wound in the side of his head convinced his aide and brother-in-law, Lieutenant Cyrus E. Dickey that he was dead. Under heavy Confederate fire, Dickey dragged the body to the side of the road and left it next to some ammunition boxes. Wallace's wife Ann had arrived unannounced the day before the battle to visit her husband. She had remained aboard the steamboat Minnehaha and was stunned to hear of his death and the loss of his body when her brother came aboard that evening.

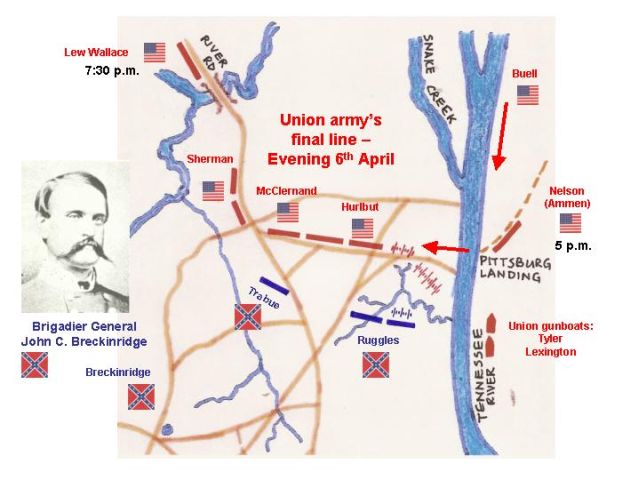

Hour after hour the Union army was driven back, closer and closer to the high ground above the landing. Grant rode along patching the lines as best he could, encouraging the officers and telling them that Lew Wallace's men were on their way. Buell arrived by steamboat in mid-afternoon and said he would get his men to the scene as quickly as possible.

Final Union line (map)

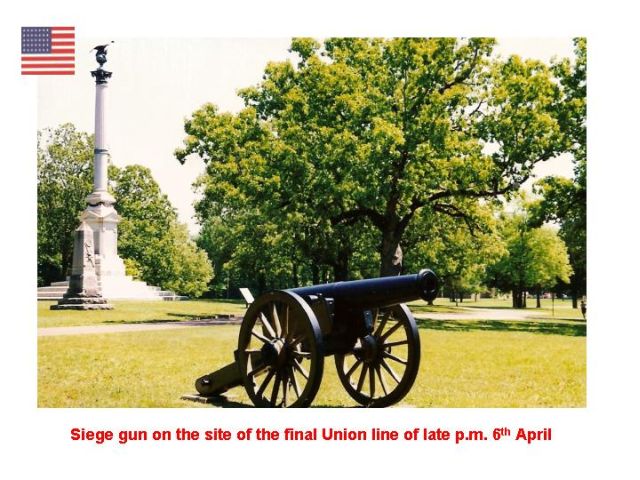

Grant's chief engineer, Colonel Joseph D. Webster, assembled all the siege guns and the field artillery in a compact line overlooking a ravine formed by a backwater of the Tennessee River. Webster had more than fifty guns and the Confederates were under fire from these guns as well as those of the navy's gunboats on the river.

Nelson's men had had quite a time of it, marching down the eastern bank of the Tennessee River over atrocious roads. They arrived opposite the landing in the late afternoon and were shipped across the river by steamboat. Clearing a way through the thousands of dispirited stragglers in the lee of the landing they took up their positions in the line. Buell's men came up by steamboat from Savannah and the crisis for the Union army was over as Beauregard ordered a halt for his exhausted Confederate brigades.

Conditions in the Confederate army were just about as disorganized as the Federal and Beauregard was now in command. Beauregard's battle plan had resulted in the four Confederate army corps being unable to keep together and there was now a lull while they sorted things out.

Finally, the lost division of Lew Wallace came marching up to take its position on the right. Wallace had had a miserable day trying to find the road that would bring him to Pittsburg Landing. He had marched his division off on the wrong road, had had to make a laborious countermarch and was now reaching the scene hours late - only at about seven thirty in the evening. His division could have turned the tables on the Confederates had he arrived early in the afternoon and Grant was unforgiving until almost the end of his life. Never to become a famous general, Lew Wallace's fame came as a novelist with "Ben Hur."

It was a horrible night for everyone - pitch black darkness, incessant rain and acute physical discomfort. Thousands of men had been wounded and the rest were exhausted. Grant tried to get some rest lying under a tree on the bluff but the pain in his injured ankle kept him awake. Around midnight he tried to find shelter but everywhere there were groaning wounded and he returned to his tree. Later the tough Sherman found him standing under the tree in the heavy rain, hat slouched over his face, with his coat collar up around his ears and a cigar clenched between his teeth. Sherman looked at him and (as he put it later) "moved by some wise instinct" not to talk about retreat, said: "Well, Grant, we've had the devil's own day, haven't we?" Grant said, "Yes" and his cigar glowed in the darkness as he gave a quick puff at it. "Yes. Lick 'em tomorrow though."

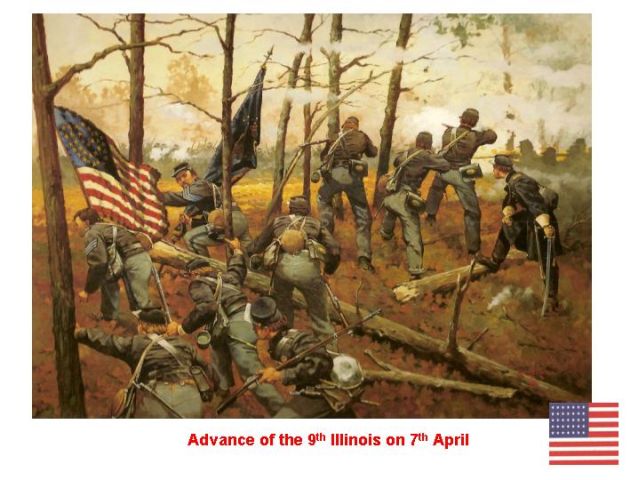

On Monday 7th April the battle resumed but Buell's soldiers were arriving at the landing, Lew Wallace's men were in place and the business was settled. The Confederates did not give way easily but by the end of the morning one of Beauregard's staff came to the general in the rear of Shiloh church and suggested that it was time to retreat. Beauregard said that he had the same idea: "I intend to retreat in a few moments." The Federal pursuit was perfunctory and Buell's army was not precisely under Grant's full control. Buell was stiff and touchy and the relationship with Grant was very delicate. Grant's army was incapable of pressing the Confederates and Buell's fresh brigades and cavalry were not ordered to do so.

Everett Peabody was found dead where he had fallen. All the buttons and shoulder straps had been cut from his uniform and his sword and pistols were gone. His officers buried him in a gun box, marking the spot with a board upon which they scrawled: "A braver man ne'er died upon the field."

At 11 a.m. during Monday's fighting Lieutenant Cyrus Dickey discovered W.H.L. Wallace's body near the place that they had left him the day before. To Dickey's great surprise Wallace was still breathing despite his horrible head wound. Passing Confederates had wrapped him in a blanket and he was carried to the landing and put aboard a transport. Dickey hastened to find his sister and Ann Wallace was overjoyed to hear that her husband was alive. General Wallace was taken to Savannah and placed in the library of the Cherry mansion where he died on Thursday 10th April. He was "conscious of my presence to the last" appears in Ann's diary. In an upstairs bedroom Charles F. Smith, the man who had begun it all by leading his expedition to Savannah, lay dying of a tetanus infection. His condition worsened by mid-month and he passed away quietly on 25th April, the last notable casualty of the Shiloh campaign.

Grant and Sherman were both heavily criticized by newspapers and politicians. Whitelaw Reid's story which appeared in the New York Herald was a shocker and presented to the country a convincing picture of a military debacle that was humiliating and disgraceful. The army had been surprised in its camps. Some men were shot dead in their tents and others bayoneted while still in bed. Everybody retreated in haste and Prentiss's division was swept away and captured by ten o'clock in the morning. Heroic resistance was described here and there but the narrative was one of unrelieved bungling. Much of what Reid wrote was demonstrably not true and he obviously absorbed the wild tales told by panicky fugitives at the landing. Grant wrote a letter to an editor in reply to newspaper criticism - something he never did again in his military career. Sherman's case was a good deal tougher. He was at the front and his contemptuous remark "Take your damn regiment back to Ohio. There is no enemy nearer than Corinth!" could not be explained away. He wrote furiously to the Lieutenant Governor of Ohio who had tried to make political capital out of criticism of the Union command: "All I know is we had our entire front covered by pickets....I had my command in line of battle before we had seen an infantry soldier of the enemy."

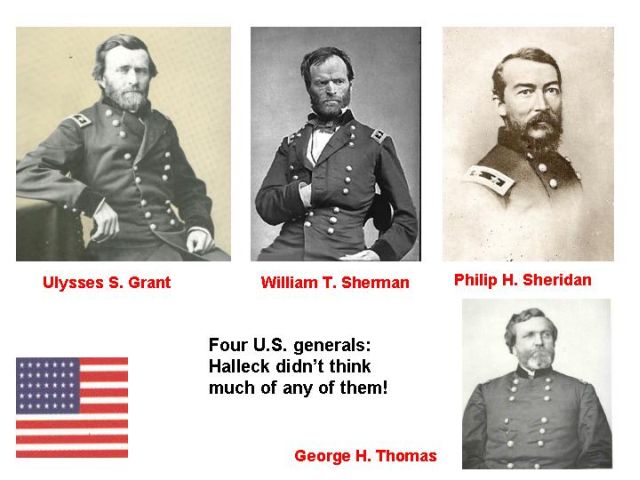

Henry Halleck took over field command for a while and acted with extreme caution until appointed General in Chief in Washington in July 1862. Until this happened, Grant was sidelined and Sherman one day found him with trunks and boxes packed, ready to leave. Sherman argued with him, prevailed upon him to stick it out and believed that it was his own argument that kept Grant from dropping out of the army altogether. In another two years Grant would be promoted Lieutenant General and given command of all the armies of the United States. It is no exaggeration to say that Grant won the war for the Union. Halleck's misjudgment of Grant as a subordinate was not so much that Grant got in his bad books as because he was a dismally bad judge of men. In the summer of 1862 he wrote that: "It is the strangest thing in the world to me that this war has developed so little talent in our generals. There is not a single one in the west fit for great command." When he wrote that his command included Grant, Sherman, George H.Thomas and Philip H. Sheridan, among others.

The battle of Shiloh had been a very near thing indeed. The Union army had beaten off an unexpected attack and one of the decisive struggles of the civil war had been won. The consequences were far-reaching. The end of the war was still three years off and in the long run many things killed the dream of Southern independence. The desperate fighting in the wilderness above the Tennessee River was one of these things and another was the unbreakable stubbornness of Ulysses S. Grant.

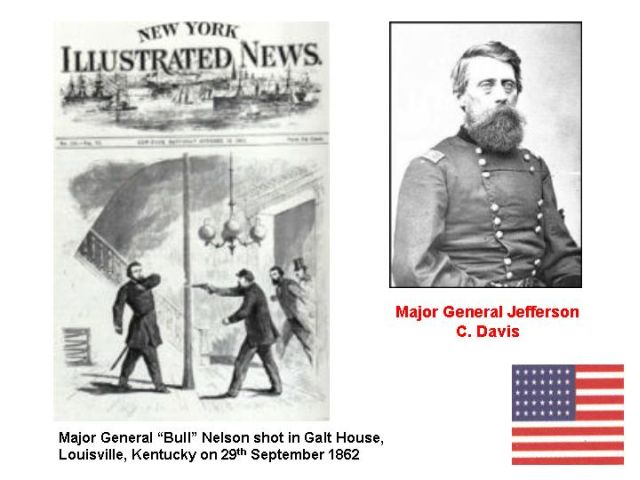

As a postscript, the fate of William Nelson is an appropriate last word. In September 1862 Braxton Bragg's Confederate Army of Tennessee had marched northwards and Don Carlos Buell's Army of the Ohio was defending Louisville, Kentucky. Nelson was his most aggressive Major General at a time when this quality was at a premium. An Indiana Brigadier General by the name of Jefferson Davis, coincidentally the same name as the Confederate President, had a personality clash with Nelson, his superior. An argument ensued in the lobby of the Galt House in Louisville, Buell's headquarters and Davis shot the big man in the chest. Buell placed Davis under arrest but before Nelson's blood had time to dry on the carpet outside his door the order arrived from Washington removing him from command and replacing him with Major General George H. Thomas. Davis was never charged and rose to the rank of Major General, a respected member of William T. Sherman's army in its campaign through Georgia and the Carolinas.

Copyright Robin Smith - email queries to him at: smithrw@yebo.co.za

Return to Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org