The South African

The South African

by Jan-Willem Hoorweg

Curtain raiser address to the Johannesburg Branch on 16 January 2020

Another title for tonight’s presentation could have been “Unravelling the mysteries of the H.L. Hunley, the ship that sank three times” because that is the story of the subject of my talk tonight.

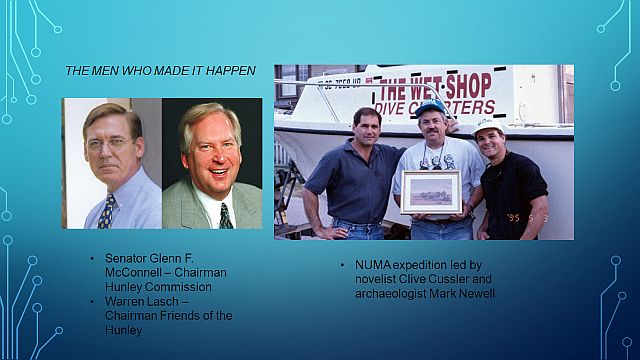

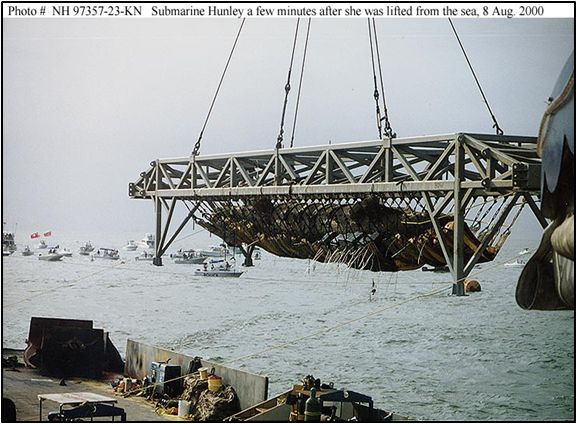

On February 17, 1864, the H.L. Hunley became the first successful combat submarine in the world with the sinking of the USS Housatonic outside the harbour of Charleston, South Carolina. After completing her mission, she mysteriously vanished and remained lost for over a century. Led by bestselling author Clive Cussler, the National Underwater and Marine Agency (NUMA)finally found the Hunley in 1995. After news spread of her discovery, it was decided to retrieve the submarine from the sea. The Hunley Commission and the Friends of the Hunley raised the necessary funds and, with the help of the US Navy, finally recovered the Hunley on August 8, 2000. She was then delivered to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, a high-tech lab specially designed to conservethe vessel and unlock her many mysteries. She is indeed a time capsule, and keeps teaching us more about life during the Civil War. The ongoing preservation work on the submarine and many artefacts found will provide clues to the archaeologists about her fate.

Through the years I have been fortunate to visit the Hunley on two occasions, first in 2004 and, most recently, in December 2018. The historical city of Charleston offers much to the traveller. Not only the place where the American Civil War started, it is also the home of the fighting lady or USS Yorktown at Patriot’s Point as well as Fort Sumter. The colonial houses and architecture of Charleston (think Rainbow Row) are wonderful, and the traditional deep friedsouthern cuisine, especially the shrimp that Charleston is famous for make this a must visit destination if you are in the southern states.

No visit to Charleston is complete if you have not been to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center located in the former Charleston Navy Yard in North Charleston. The center is named after Warren F. Lasch, who was Chairman of the Friends of the Hunley during the Hunley’s recovery.

Warren Lasch Conservation Center

The ships

The idea of underwater warfare of course was not new, the Turtle being the first submarine used to attack an enemy warship almost ninety years earlier, during the American Revolutionary War in 1776.

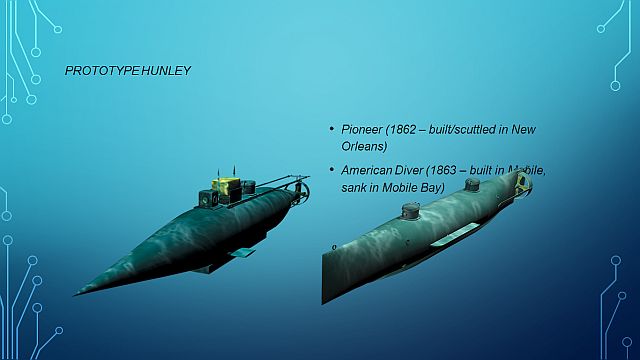

She was named after one of her inventors, Horace Lawson Hunley, who provided the financing for James McClintock to design and build two prototype submarines, namely the Pioneer and American Diver.

Pioneer and American Diver

Even at this early stage, the builders experimented with electrical and steam propulsion, before finally settling on a simple hand-cranked propeller. After the loss of the American Diver during harbour trials Hunley provided the financing for the boat eventually named after him.

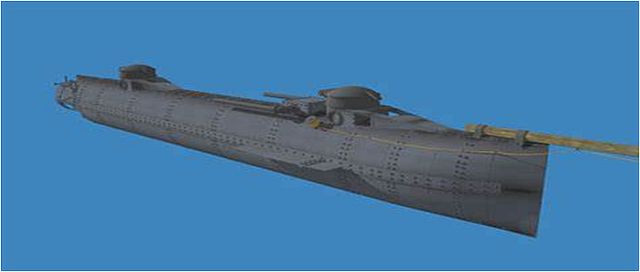

Variously referred to as a fish boat or torpedo boat, the Hunley was in fact built for purpose. A crew of eight, featuring seven to turn the hand cranked propeller, and one to steer and direct the boat. There were ballast tanks at each end of the boat, flooded with valves or pumped dry by hand pumps. There were weights bolted to the underside of the boat, that could be released from inside the sub in case of an emergency. As an aside, the Hunley was discovered with these weights still attached. Two small watertight hatches atop two conning towers equipped with small portholes, one forward and one aft assisted with entrance and exit.

As armament a towed floating explosive was initially considered. The submarine would dive underneath an enemy ship, surface beyond her, and draw the towed explosive charge against the hull. This however became far too dangerous because of the line fouling up the screw.

A spar torpedo hereafter became the armament. A copper cylinder containing 135 pounds (61kg) of black powder was attached to the 22 foot (6.7 m) long wooden spar. Initially containing barbs to jam inside the wooden hull of a ship, there is evidence now the torpedo on the Hunley was set off electrically, by pushing against the hull, exploding on contact.

Hunley

Interior view cutaway

The Hunley was not a lucky ship, sinking once during trials, resulting in the deaths of five of her crew, and once more after a mock attack on October 15, 1863, this time taking all her crew with her, including Horace Hunley himself, who had joined the crew for the exercise. Both times Hunley was raised and returned to service. The second sinking led General Beauregard, the Confederate commander in Charleston forbidding the boat to attack underwater, and declaring “it is more dangerous for those who use it than to the enemy”

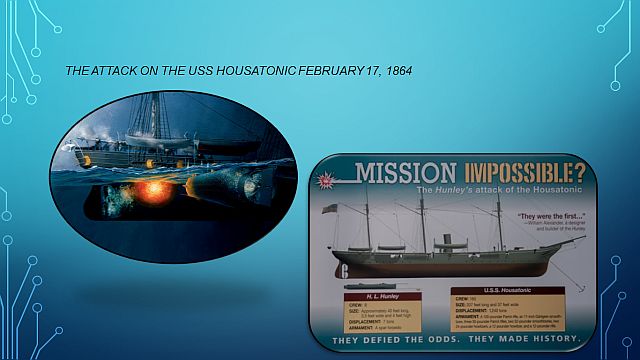

The attack

The attack on the Housatonic, a 1 200-ton wooden-hulled steam powered sloop of war with 12 cannons stationed at the entrance to Charleston harbour, approximately 5 miles (8km) offshore was a success, resulting in the sinking of the Union ship with the loss of five of her crewmen. The Confederate troops in Charleston received a signal of a successful attack, and lit a fire to guide the Hunley home, but she never returned.

Years later, when the area around the Housatonic was surveyed, the Hunley was discovered on the seaward side in approximately 27 feet (8.2m) of water, under several feet of silt, resting on her starboard side at a 45 degree angle, with a thick encrustation of rust bonded with seashell particles and sand, indicating that the ocean current had been going out following the attack.

The discovery of the little sub has been described by naval historians as the most important find of the century. The submarine and its contents are valued at more than 40 million Dollars.

Men behind the project included Warren Lasch, President Friends of the Hunley, a successful businessman and driving force, Senator McConnell, Chairman South Carolina Hunley Commission, navigating different government jurisdictions and providing political clout, and NUMA expedition with Clive Cussler.

The Recovery

The actual recovery plan was a well-coordinated operation and involving much preparation at an enormous cost. This involved the excavation of the site around the Hunley (40 ft - 12.2m - wide and 130 ft - 39.6m - long), exposing the top of the submarine, two enormous 18 by 12 ft (5.5m x 3.7m) suction piles(as used in deep water oil rig mooring systems) to provide a stable platform for the recovery work, truss installation over the submarine and attached to the suction piles, insertion of 30 slings underneath the submarine, and attaching these to the truss. Each of these slings had a monitoring device to monitor weight distribution. Each sling injected with inflatable foam, forming a cradle to lift the Hunley off the ocean floor.

The excavation culminated with the raising of the Hunley on August 8, 2000, to be greeted by a cheering crowd on shore and on surrounding water craft. The harnesses and cradle helped lift the Hunley on to the recovery barge.

Some of the press coverage of the raising

Back on (dry?)land

Her new home

She was now shipped back to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, where she was placed in a 75,000-gallon (284kl) steel tank filled with chilled fresh water to help protect and stabilize the vessel.

Hunley resting in the empty tank

and under fresh water

With the Hunley now in the conservation tank, it bought the scientist time to decide on how the excavation process would start, as well as develop a plan to ensure the submarine’s survival. The final plan took years to complete and much planning research and testing went into it. Submitted and approved by the US Navy, the 171-page document outlines an innovative end process for the preservation of the submarine.

On February 16, 2001 three hull plates were removed, to reveal the interior of the submarine for the first time in 137 years. The hull kept its structural integrity during this process.

The Crew

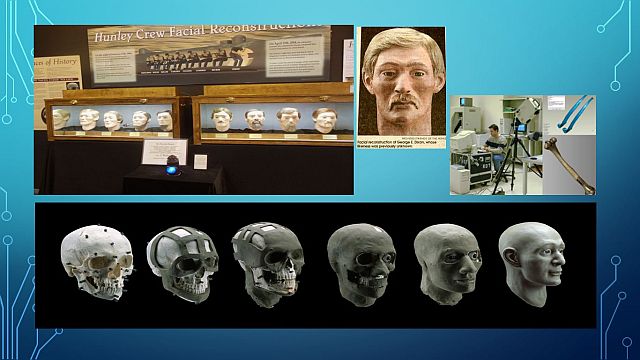

Reconstruction of crew faces

In preparation for their funeral the Hunley project created visual reconstructions of the men’s faces. This was achieved through a complex and lengthy process, and would give the men a proper identity, with a proper personal history, and not be strangers to the world.

The crew positions indicated that the men had died at their stations and were not trying to flee the sinking submarine. The identities of the men, apart from the commander George Dixon, remained a mystery for some years. Through the help of Smithsonian Institute physical anthropologist Douglas Owsley, thepuzzle was solved. Chemical signatures on the men’s teeth indicatedthe American and European diets. Four of the men had eaten plenty of corn, an American diet, whilst the others ate mostly wheat and rye, a European one. The identification process was completed in 2004 through examination of Civil War records and conducting DNA tests with possible relatives. From Europe:Arnold Becker from Germany, Corporal Johan Fredrik Carlsen Denmark, C Lumpkin (British Isles) and Augustus Miller (former member of German Artillery). Lieutenant George E Dixon commander of (Alabama or Ohio), Frank Collins (Virginia) Joseph Ridgeway (Maryland) and James Wicks (North Carolina)

Their Burial in April 2004

Interment in Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina. 6000 re-enactors and 4000 civilians wearing period clothing. Colour guards from all five branches of US military wearing modern uniforms. All buried with full Confederate honours, with the 2nd Confederate national flag, known as the Stainless Banner. Interestingly, a few of the descendants of the men had been traced, and attended the funeral, giving it a more personal feeling.

The funeral

Conserving the vessel

During the first number of years of excavation, the Hunley was kept in her cradle, as she was lifted from the seabed, resting at a 45-degree angle. This made it impossible to access part of her underside. As the inside of the Hunley had been excavated during these years, almost 11 tons of sediment encasing the Hunley’s crew remains and personal belongings, was removed. There rightly was concern that this would impact on her structural integrity. By moving the Hunley to an upright position and removing the support slings, the scientists would also be able to start work on removing the concretion that coated the outside of the vessel. The rotation process was completed over a period of 3 days in June 2011.

The next phase involved the removal of the thick encrustation of sand, sediment and seashells. The Clemson University scientists removed over 1, 200 pounds of encrustation through chiselling using small hand tools, drills and chisels over a period of one year starting in 2014. The same process then was repeated on the inside. This naturally was extremely difficult to do, working in the confines of a small four-foot diameter space.

Deconcreting the outside

More cleaning

Interior deconcreting

Personal items found

Pairs of before and after photos of personal items from the Hunley

Union Identity tag

In 2001 a Union identification tag was discovered, leading to much speculation what such a tag would be doing on board a confederate vessel. Was there perhaps a spy on board? A saboteur?

The tag bears the name of Ezra Chamberlain, who served with the 7th Connecticut Infantry. However, the mystery was solved when DNA testing with a descendent from the crewmember wearing the Union tag could confirm that he was not Pvt Chamberlain of Connecticut, but Joseph Ridgaway from Maryland. It seemed that both men fought – on opposing sides - during the Battle of Morris Island in 1863. Records indicate that Chamberlain died of wounds received during the battle. The tag could have been a battlefield souvenir, or given to Ridgeway to give to Chamberlain’s family after the war.

Binoculars

Wooden bench

The wooden bench took several years to restore. This is the bench the crew sat on while cranking the submarine. It was removed from the Hunley in 2005. It consisted of three one-inch thick pine boards, 18 feet long combined, and originally painted white. Waterlogged and severely corroded, it was soaked for several years in a synthetic water-soluble wax. This enabled the wax to strengthen the wood cells so that the bench could undergo freeze drying. The drying process took approximately one month, and the wood lost 50 percent of its waterlogged weight during this time. This now enables researchers to find textile imprints of the crew member’s pants when the paint was still fresh.

The lantern

A signal light has long been a central event in the unsolved mystery of Hunley’s disappearance. Historical records indicate that the crew would signal after an attack on one of the Union ships. Confederates on land would then guide them back to shore by lighting a fire. This lantern was found in the crew compartment. It was very deteriorated and took conservators years to restore this extremely delicate piece of maritime history.Whether this was the actual lantern used for signalling is open to debate

Coin

During the excavation of the Hunley, a $20 gold coin minted in 1860 was discovered on Dixon’s hip bone. It was warped from the impact of a bullet, and traces of lead were discovered on the coin. One side of the coin bears the image of Lady Liberty, the other was sanded and inscribed with the following words: Shiloh, April 6th, 1862, My Life Preserver, G.E.D. This coin had absorbed the impact of a bullet during the Battle of Shiloh, and most probably saved Dixon’s leg, and maybe even his life.

Dixon's jewellery

Sifting through sediment at Dixon’s station, scientists discovered this beautiful diamond ring and brooch found between two layers of waterlogged cloth, indicating he probably carried the pieces in his vest pocket. The gold ring holds 9 diamonds weighing together about one carat. The brooch has 37 small diamond amounting to two carats. Jewellery would have been extremely valuable, particularly during war-time, indicating he probably carried them for safekeeping.

The gold pocket watch of Lt Dixon was a completely different conservation process, and likened by one of the conservators as completing complex brain surgery, as the inside of the watch consisted of different materials like steel, paint, porcelain and brass, each having to undergo a different conservation process, and each preserved separately, hereafter the tiny items were re-assembled one by one again and put back in the gold casing.

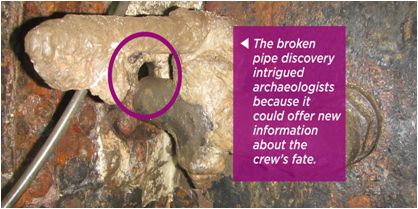

Theories of her sinking

So, what could have caused the submarine to disappear? Well there are a number of theories, but we will probably never know what exactly happened on that fateful night, when she slipped beneath the waves a final time.

Other recent discoveries include a gearing system that could have helped enhance the crew’s efforts while cranking the sub.

What does the future hold for this little submarine? The final phase of Hunley’s restoration, and one that is ongoing, involves removing the salts that threaten the Hunley’s existence. In 2014 the 75 000-gallon tank was filled for the first time with a bath of sodium hydroxide. Corrosion along the seams that hold the submarine together will be soaked out over a period of approximately 7 years. Once the salt has been absorbed the tank is flushed out and the process is repeated until such time the level of salt in the iron is deemed low enough to take Hunley out of her protected environmentit is deemed safe for her to be put on permanent display. Plans are underway for a world class maritime museum, which will house the Hunley, as well as Union and Confederate artefacts, together with other important naval collections.

Return to Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org