The South African

The South African

This is a summary of a talk given by WCMHC member and historian of science Dr. Michael Schaaf in Cape Town on May 15, 2025.

Why did German scientists fail to build either an atomic bomb or a functioning reactor during WW II? Was it incompetence, ignorance, or calculated choice? After the discovery of nuclear fission in December 1938 and the detection of secondary neutrons in April 1939, physical chemist Paul Harteck drew the attention of the Reich War Ministry to the military possibilities of this discovery. On 24 April 1939 he wrote: “We take the liberty of calling to your attention the newest developments in nuclear physics, which, in our opinion, will probably make it possible to produce an explosive many orders of magnitude more powerful than the conventional ones.[…] That country which first makes use of it has an unsurpassable advantage over the others.

Paul Harteck (1902-85)

The Army appointed a little-known army physicist named Kurt Diebner to investigate the matter. In mid-September, the newly appointed Diebner and his assistant Erich Bagge convened a meeting in Berlin to discuss the practical possibilities of uranium wartime research. In attendance at this gathering were many of the biggest names in German physics and chemistry, including Otto Hahn, Paul Harteck and Walther Bothe. The scientists nicknamed their gathering the ‘Uranium Club’.

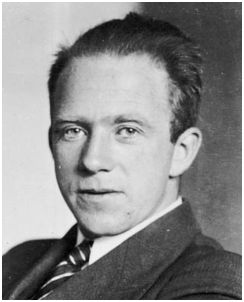

To his list of attendees, Bagge had also extended an invitation, almost as an afterthought, to his own mentor and advisor, Werner Heisenberg. While arguably the leading physicist remaining in Germany, Heisenberg, a devout theoretician seated at the table full of experimentalists, was the odd man out. Most of the research and work that had made him famous was based in mathematics and thought experiments, not in constructing experimental setups out of concrete and steel, or in the mundanity of collecting actual data. But Heisenberg’s international stature and fame made him welcome among his colleagues at the meeting.

Werner Heisenberg (1901-76)

Heisenberg was given the task of finding the theoretical foundation for an energy producing reactor or bomb. At the end of 1939 Heisenberg produced the first of two classified papers in which he showed that a nuclear reactor with natural uranium needed either graphite or heavy water to moderate the neutrons and control the nuclear chain reaction. Graphite didn’t look promising as it absorbed too many neutrons due to its impurities, but heavy water would work. The problem was that Germany did not possess significant reserves of heavy water. The world's only heavy water factory was located in Rjukan, Norway. This only changed with the German invasion of Norway in April 1940.

Rjukan, Norway

In his calculations and assumptions Heisenberg had made several critical mistakes. The first was his calculation of how much uranium would be required. The critical mass, or the amount of uranium required to create a self-sustaining chain reaction or an explosive instantaneous reaction, is in part related to the distance a neutron must travel between fission events. Heisenberg assumed that this distance was much larger than it actually is, and as a result his initial calculations of the critical mass of uranium-235 were on the order of several tons – far larger than the actual size required (in reality, the critical mass of uranium-235 is only about 50 kg). As uranium-235 is only present at 0.7% in natural uranium, it must be enriched. Separating out several tons of uranium-235 from several hundred ton of natural uranium would practically be impossible as functioning enriching methods didn’t even exist and would require an enormous amount of energy, industrial capacities and money. And even if enough material was somehow obtained, the sheer weight of a resulting bomb would largely rule out the possibility of an aerial delivery.

Whether out of fear of repercussions, respect for the revered scientist, or a widespread lack of understanding of the problem at hand, none of Heisenberg’s colleagues corrected his mistake.

As a result of these impediments, the German scientists began to pull back from the notion of using nuclear fission to build a weapon. Instead, they turned their attention, and their rhetoric about the research, toward using this new technology as a source of energy. Their primary goal became building a functioning reactor – or a “uranium machine”, as they called it.

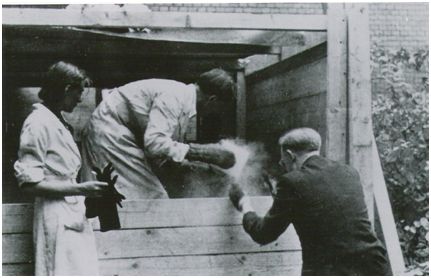

The first reactor experiment in the world.

(Hamburg, 1940)

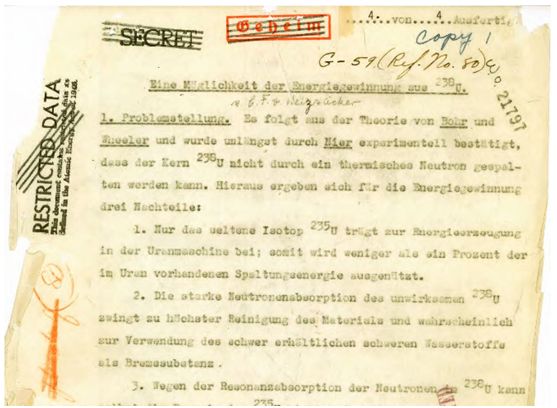

Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker:

“One possibility of generating energy

from 238U” (July 1940)

The author with Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker in 1996.

Repeatedly pointing out the theoretical possibility of an atomic bomb to official authorities allowed them to maintain the status of their research as “important to the war effort” and to classify the scientists involved as “indispensable”, meaning they were not required to go to the front. Incidentally, the uranium project also enabled them to revalue or rehabilitate modern theoretical physics, especially quantum physics and the theory of relativity, which the Nazis viewed as Jewishly degenerate. From 1943 onwards, the relocation of research facilities scattered throughout the Reich, shortages of materials and disputes over competence increasingly delayed the work of the researchers. At the beginning of March 1945, the last reactor experiment took place in Haigerloch, Southern Germany. The reactor consisted of 1.5 t uranium, 1.5 t heavy water (as a moderator) and 10 t graphite (as a neutron reflector).

Replica of the last German reactor experiment

in the Atomic Cellar Museum Haigerloch.

However, no criticality occurred, even after all available heavy water had been filled. The neutron density in the filled setup increased by 6.7 times compared to the empty measurement. While this value was twice as high as in the previous experiment, it was still not enough to achieve a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction.

At the same time, the final experiments in uranium enrichment using the ultracentrifuge were taking place in a small building on the grounds of a silk mill in the northern German town of Celle.

The centrifuge laboratory was located

behind the two right windows of this building.

While Harteck's research group in Celle endeavoured to produce at least a few grams of uranium 235 enriched by a few percent, the uranium enrichment facilities at Oak Ridge in the USA had been producing one kilogram of highly enriched, weapons-grade uranium 235 about every four days since January 1945.

In his book Alsos Sam Goudsmit, the scientific director of an American special unit to track down the scientists involved in the “Uranium Club”, wrote after the war: “It was so obvious the whole German uranium set up was on a ludicrously small scale. Here was the central group of laboratories, and all it amounted to was a little cave, a wing of a small textile factory, a few rooms in an old brewery. To be sure, the laboratories were well equipped, but compared to what we were doing in the United States it was still small-time stuff.

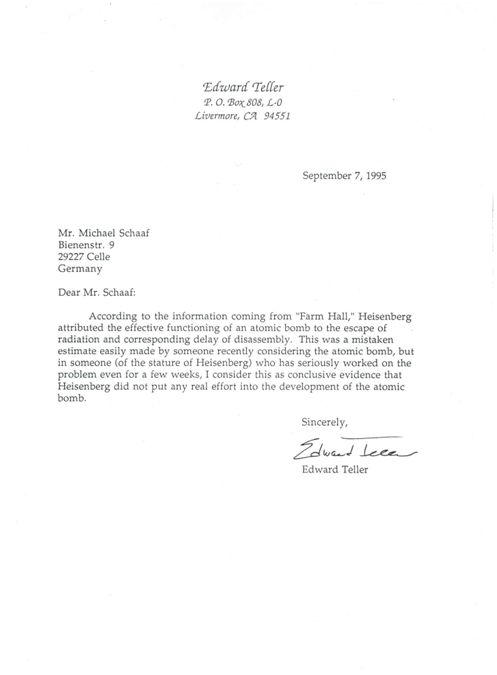

The Farm Hall Transcripts, released in 1992, confirm that German scientists never seriously considered an atomic bomb. This is also corroborated by a letter from Edward Teller to the author.

Heisenberg's priority during the war was not the uranium project, but rather basic research such as the S-matrix theory and cosmic radiation.