The South African

The South African

This is an abridged summary of a talk given by WCMHC member and historian of science Dr. Michael Schaaf in Cape Town on August 21, 2025.

History is not what was, but what we as a society know about what was. Therefore, we must continually remember, retell, and awaken the past; we must delve into it and, in the face of what is today, reevaluate what others before us already believed they knew.

The history of the atomic bomb and their subsequent use in Japan cannot be separated from the developments in Germany and the worries of the exiled Jewish physicists in Britain and the USA. The two lectures in May and August should therefore be regarded as complementary.

In my talk I tried to throw spotlights on some perhaps lesser known aspects of this complex topic; shift the focus and get rid of beloved legends.

The Einstein-Szilard letter to President Roosevelt from August 2, 1939 is often regarded as the start of the Manhattan Project. This is more than an exaggeration. The letter is probably one of the most overrated documents in

history.

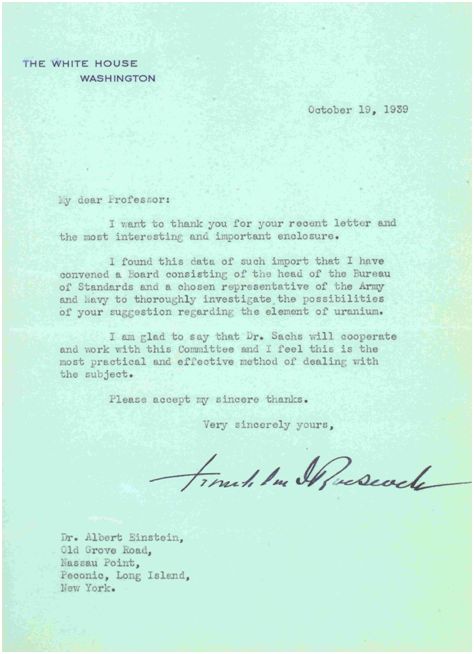

It took two and a half months before Einstein received a reply to his alarming letter. He must have been even more disappointed when he read Roosevelt’s lines.

Roosevelt’s response to Einstein’s letter from August 2, 1939.

Even someone like Einstein, who had only been living in America for a few years, must have realized that the phrase "extremely interesting" concealed a polite rejection of his proposal.

Presidents are constantly bombarded with useless ideas. When the person putting them forward is famous, politicians feel obligated to show a certain amount of courtesy. But one thing was clear: Roosevelt and his advisors didn't believe the claim that a single bomb could destroy an entire harbor.

Roosevelt's advisory staff consisted of honorable but not particularly qualified individuals. The amounts the government provided for nuclear fission research were initially ridiculously small: $6,000 for a whole year! No wonder not much happened for months.

In fact, it was only thanks to Otto Frisch's initiative that the nuclear weapons program was pushed forward with determination, and even then only from the fall of 1941.

Later, Einstein said more than once that he regretted having written the letters to Roosevelt: "Had I known that the Germans were incapable of building an atomic bomb, I would never have lifted a finger."

Before the war the physicists in Germany and in the rest of the world were a highly interconnected community of scientists - now they were rivals. During the war Werner Heisenberg, the leading physicist in the German “Uranium Club” and Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific director of the Manhattan Project, were antagonists in a race that didn’t exist.

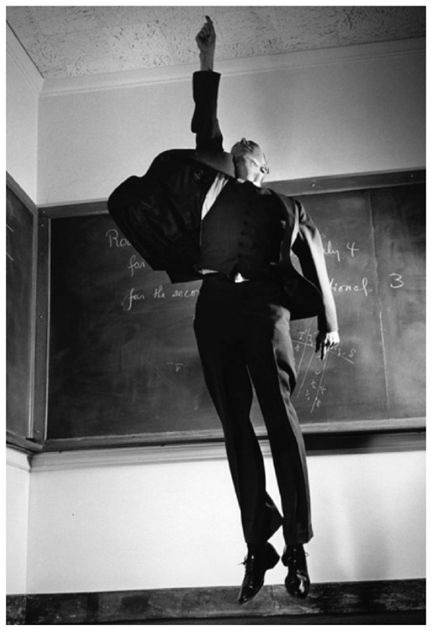

Edward Teller, the “father of the hydrogen bomb” once said: "Physics is simple, physicists are not." Oppenheimer was an eccentric and complex character. As a student he almost killed two people. He was a talented theoretical scientist but useless as an experimenter. He was influential but not a first class physicist like Einstein, Bohr, Heisenberg or Pauli. Oppenheimer spoke many languages but his publications on theoretical physics were mostly incomplete. No wonder he received only four Nobel Prize nominations – the same as his German colleague Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker – but never received the prize.

Six feet tall and 100 lbs: Robert Oppenheimer

He and his wife Kitty were fluent in German, Kitty even spoke German without an accent. She was born in Germany. Her mother was the cousin of German Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel who would later sign Germany’s unconditional surrender in Berlin on May 8, 1945.

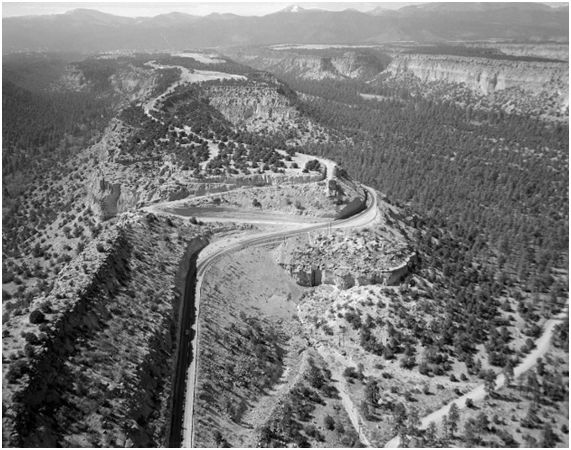

Los Alamos, situated on a remote mesa in New Mexico, had initially been planned for only 100 scientists. In 1945 it housed 1000 scientists, 8000 people in total. The living conditions were poor but the spirit was high.

The road to Los Alamos in the 1940’s

Oppenheimer managed to bring together the crème de la crème of the country’s scientists to Los Alamos to work on the atomic bomb, amongst them 18 current and future Nobel Prize winner like Hans Bethe, Enrico Fermi, Richard Feynman and Emilio Segrè. When they met for their weekly colloquia there was more scientific brainpower accumulated than at any time since Isaac Newton dined alone.

The average age of the physicists was 29.4 years. Oppenheimer chose well, as they say that at the age of 30, physicists enter an intellectual menopause, beyond which they sink into a drought of unimaginative ideas.

In 1944 the work on the two bomb types (uranium bomb and plutonium bomb) fell into a crisis, as is became increasingly clear that there would only be sufficient enriched U-235 for one bomb in 1945 and that the simple gunshot design wouldn’t work with plutonium due to its high spontaneous fission rate. In this situation Oppenheimer showed his leadership skills when he decided to continue with uranium enrichment while simultaneously developing a completely new design for the plutonium bomb.

There were at least four Spies at Los Alamos who passed on secret informations to the Soviets: Klaus Fuchs, David Greenglas, Theodore Hall and Oscar Seborer. Greenglas later became state witness and testified against his sister Ethel Rosenberg who, together with her husband Julius, was subsequently sentenced to death. Espionage saved the Soviets 1-2 years of development time for their first atomic bomb which detonated on August 29, 1949.

The complicated implosion design for the plutonium bomb was tested in the morning of July 16, 1945. On that day the sun rose twice as the flash of light by the explosion was “Brighter than a Thousand Suns” (the title of a popular book by Robert Jungk on the history of the atomic bomb). Afterwards Kenneth Bainbridge, the director of the so-called “Trinity Test”, said to Oppenheimer: „Now we are all sons of bitches.“

Meanwhile the war in Europe had ended. The question for General Groves and the military was not, if, but where and when the new weapon should be used against Japan.

A 1995 Gallup survey showed that 50 years after the war, an overwhelming majority of Americans who were alive at the time that World War II ended agreed with the decision to use atomic weapons against Japan in 1945, presumably because of the prevailing myth that the only alternative was an invasion.

One reason for the prevalence and tenacity of popular misconceptions about the use of the bomb is the mythology that has surrounded the central figure, President Truman. He was, through no fault of his own, ill-informed and poorly prepared for the responsibilities he assumed when he became president after Roosevelt’s death in April 1945.

There is no single document that shows Truman’s decision to use the bomb. There were two military orders that instructed the Army Air Forces to deliver the bomb on Japanese cities, both of which resulted from informal discussions between Groves and other Army leaders.

Japan’s situation was dire. It had lost its fleet and had hardly any planes. The food and oil supplies from the occupied territories had come to a halt due to the American Naval blockade. Since the bombing of Tokyo on March 10, 1945, with a death toll of 100 000 the deadliest bombing in the history of mankind, 66 cities had been destroyed and 400 000 killed. Japan was ready to surrender.

The Potsdam Declaration called for an unconditional surrender of Japan otherwise there would with be “prompt and utter destruction”. Nothing was said about the status of the Emperor, which was the only obstacle on the way to end the war. The Americans knew that the Japanese would never surrender if their Emperor would be taken to court.

Stalin did not sign the declaration which made the Japan believes that the Russians were still willing and able to mediate a ceasefire.

One of General Groves’ main concerns was to preserve some Japanese cities from conventional bombings in order to demonstrate precisely the impact of the atomic bomb on an untouched city. Americans officials often claim that the atomic bombs were directed at military targets, but the aim points the target committee chose were not military installations but the geographical centre points of cities. The bomb wasn’t going to explode on the ground to hit bunkers but to explode at a height of about 600 m in order to destroy as many houses as possible.

The author behind one of the original spare casings of “Little Boy”.

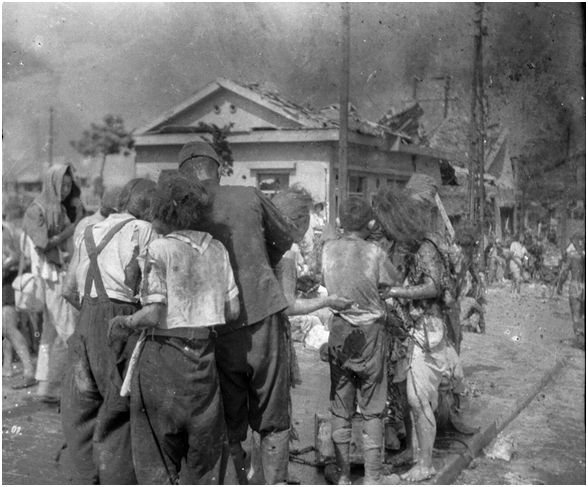

The heat of the explosion of “Little Boy” over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 was so intense that even hundreds of meters from Ground Zero brick tiles threw bubbles and humans evaporated often leaving nothing than a shadow on the concrete. The mushroom cloud reached a height of 14 km high and was 1km in diameter. 4 km was flattened. Between 70 000 and 140 000 people died on that day.

“The viewfinder was clouded over with my tears.”

One of only five photos taken by Yoshito Matsushige

on 6 August 1945 in Hiroshima.

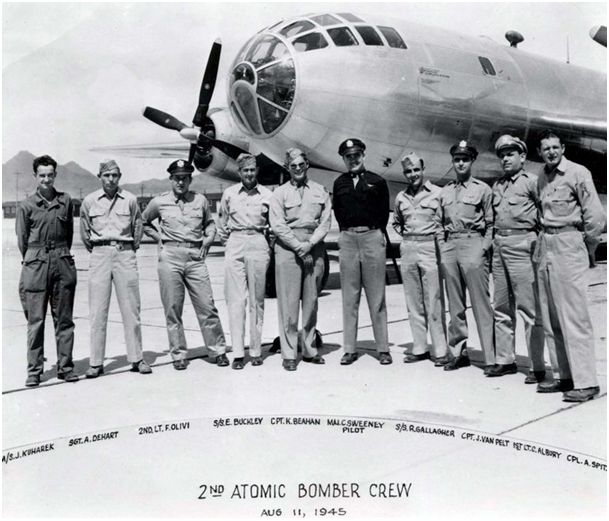

Organizationally speaking the Hiroshima mission was a milk run. But on the Nagasaki mission almost nothing went according to plan.

On the flight to the Pacific Island of Tinian, the plutonium core was rolling around in the back of the plane. Plugs of a cable in the firing unit of the assembled “Fat Man” bomb had been put together in a wrong way. Last minute changes (a different pilot for “Bockscar”, the bomb carrying plane, a new rendezvous point, higher altitude route, camera assistant of the observation plane was kicked of the plane) and a broken fuel pump almost prevent the start of Bockscar.

On the way to Kokura an alarm light started blinking – Fat Man was fully armed and ready to go off! At the rendezvous point two of the three planes circled for 45 min. waiting for the third plane. Kokura was blanketed in thick smoke. Flak started bursting. Due to the “purple operation” (Army pilot and Navy commander) a competence conflict broke out on board about what to do. The pilot was ordered to fly to the secondary target Nagasaki. Due to low fuel and clouds over Nagasaki the bombardier had only one chance to drop the bomb. He missed the target by 3 km. Bockscar just made it to Okinawa, the next possible Air base.

6.2 kg: The amount of plutonium in the Trinity Test

and in the Nagasaki bomb.

The detonation released the energy equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT, six kilotons more than the Hiroshima bomb. This energy resulted from only 1 kg of the 6.2 kg of plutonium that fissioned.

How many people died in Hiroshima and Nagasaki? The most credible estimates cluster around a “low” of 110 000 mortalities and a “high” of 210 000.

One day before “Fat Man” exploded over Nagasaki Stalin had invaded Manchuria, breaking the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact from 1941. Stalin wanted his share of Japan before it surrendered to the United States.

The Japanese knew what had happened to the imperial family after the Bolsheviks seized power. To save the Emperor, it was necessary to prevent the Soviets from occupying Japan. Surrendering to the Americans was the lesser evil. The atomic bombs allowed the Japanese to save face, since they hadn't lost on the battlefield.

In the last decades historians reached a broad consensus on some key issues surrounding the use of the bomb:

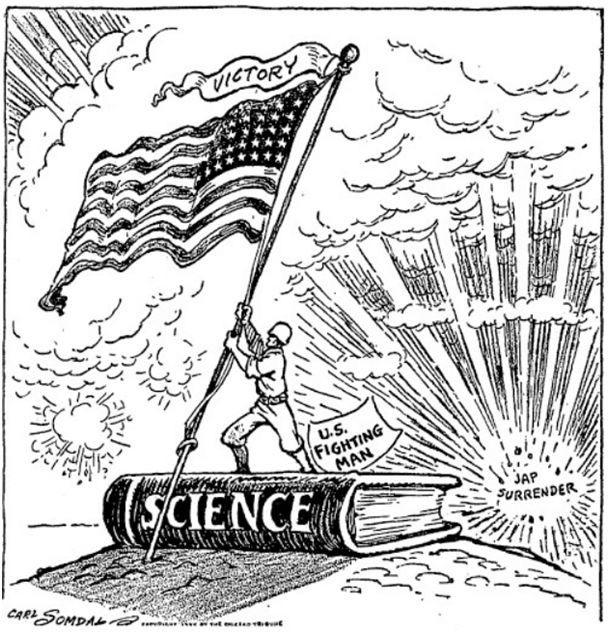

“Mighty Atoms” (Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1945)

The Second World War and the atomic bomb elevated the role of science and technology and transformed them into crucial instruments of national power. Massive investments in research and development during and after the war marked the beginning of “Big Science” and the founding of important national laboratories like Los Alamos (1943), Argonne (1946), Brookhaven (1947) and Lawrence Livermore (1952).

The existential threats to humanity occur on very different timescales: from decades in the case of climate change to weeks in the case of pandemics. A threat with an even shorter timescale has fallen out of focus in the aftermath of the Cold War: the nuclear threat. A global nuclear war would wipe out a large part of humanity within a few hours.

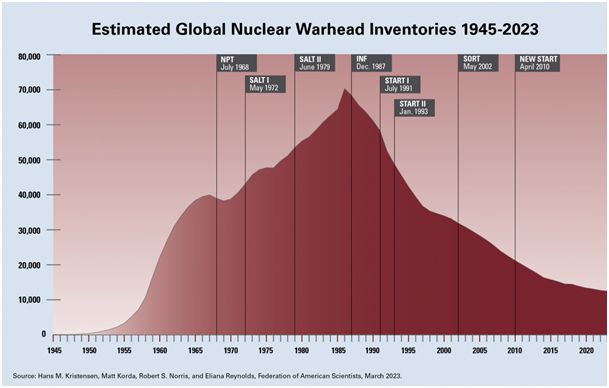

Even before the bomb was completed, Oppenheimer and some of his colleagues, such as Bohr and Szilard, foresaw that proliferation and increasingly powerful bombs would not make the world safer. The Manhattan Project cost approximately $34 billion in today's currency. The United States alone now spends $60 billion annually on nuclear weapons.

The nuclear arms race reached its peak in the mid-1980s, when there were over 60,000 warheads worldwide. Now there are "only" around 12,000, which still equates to three nuclear warheads per major city (>100 000 inhabitants) on Earth (including Cape Town!). Compared to today’s nuclear weapons the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were mere like firecrackers. The yield of modern nuclear warheads is about 5-40 times stronger than the Nagasaki bomb.

While the world has been fortunate enough to avoid global nuclear war several times since Nagasaki, Putin's nuclear saber-rattling and Kim Jong-un's threats of escalation demonstrate the fragility of the so-called balance of terror. While nuclear weapons used to be the weapons of the powerful during the Cold War, they now seem increasingly to be becoming the weapons of the powerless. The case of North Korea, in particular, has significantly reduced the willingness of potentates to engage in nuclear disarmament initiatives, as they have seen that only the possession of nuclear weapons seems to have saved the Kim regime from collapse.

The danger of a global thermonuclear war remains what it has been since the 1950s: the greatest threat to humanity.

And so, what Oppenheimer said at an event in Los Alamos in October 1945, is truer today than ever: "The people must unite, or they will perish!"