The South African

The South African

On Friday, 13 June, 1963, 24 Brigade['Fire Brigade'], East Africa, on stand-by for deployment in Africa and the Middle East had been on full alert for 72 hours as there had been rising unrest in theBritish Protectorate of Swaziland (now Eswatini), situated between the Republic of South Africa and Moçambique (now Mozambique). There had been three strikes and multiple sites of violence over three days in a small country with a police force of only 350 personnel that was unable to cover multiple events at long distances. The strikers were calling for release from jail of 12 labour leaders.

There had been no deaths or serious casualties. No evacuation of Europeans had been contemplated.

Disturbances had begun at the British- owned Havelock asbestos mine, near the northern border with South African, three weeks previously, with 1 500 workers on strike. On 13 June the Ngwane National Liberation Congress [N N L C] had called for a general strike in the capital, Mbabane, and included the 1 500 workers on the lowveldt sugar plantations at Big Bend near the Moçambique border. Police had had to use teargas and open fire; 63 strikers had been arrested. Trouble diminished when strike leader, Dumisa Dlamini and his associates, were jailed. The crowd had to be told not to use sticks.

On Thursday June13th at 18h30 a 'go ahead' signal from the War Office had been received by East Africa Command in Nairobi, Kenya. Within 5 hours, in response to the rising unrest, the acting GOC of 24 Brigade, Brigadier DW Jackson, had started the airlift of 700 troops of 1 Btn Gordon Highlanders, stationed on the Rift Valley at Gilgil, to RAF Embakasi in Nairobi. The airlift, commanded by Brigadier D Lloyd-Owen, was to be completed by 15th. There was no secrecy as there had been for an earlier Kuwait mission; we were told that it was going to be cold.

Acting Commander East Africa, Wing Commander F Simmons, made available 6 Bristol Beverleys and 3 Britannias for the airlift.

At the same time the 2 Btn Scots Guards was being sent to Zanzibar to cover the island's elections. The Gordons were to be replaced by the Loyal Regiment in Britain, starting the next day.

My command, B section of 24 Field Ambulance, consisting of 20 personnel including a cook and 2 RASC drivers, was roused at 02:00 and at 03:30 left for Templar base at Kahawa, on the outskirts of Nairobi, home of the Scots Guards. The section had to be split into 2 sub-sections of 10 persons each, the second party to remain under Sgt Forsythe. At 06:00 my party left Templar base and arrived at Embakasi, Nairobi's airport, at 06:45. Here I met my new CO, Col Robinson, as well as Brig Jones and the padre. We took off at 08:15 on a Bristol Britannia, arriving at Salisbury [Harare] at 12:05 with a beautiful view of the volcanic summit of Kilimanjaro on the way.

A Rhodesian army lieutenant led us by lorry to a hangar on the military side of the airport [New Sarum]. Here I met the quartermaster general and asked about liaison with the medical facilities and their availability as a half-way post for casevacs to Nairobi. Later I met Maj D McIntyre who showed me around their well-appointed 12 bed medical centre.

Any severe medical emergencies could be referred from there to the Andrew Fleming Hospital in Salisbury rather than being flown to Nairobi, since an immediate flight might not be available. I met Squadron Leader Ian Houston (of RAF Aden) who had been sent to run a casevac centre, which I thought not really necessary. Lunch and dinner followed. I was given a room in the MRS (Medical Reception Station), but could only sleep until 01:30 for that was when the next stage of the airlift was to take place. At 02:00 we reported to Air Movements as Chalk II (being a group of passengers assigned for a flight), and took off at 03:00 for Swaziland, this time in the tail section of a 4-engine Bristol Beverley transport aircraft.

We flew in low over the Usutu Forest to the new Matsapa Airport, landing at 06:00. The RAF was not expecting us as there was no link with Mbabane. We were told that Chalk I was stuck in Bulawayo and part of Chalk II was still in Salisbury, but Chalks IV, V and VI had arrived. We were also told to wait and to our surprise tea and snacks appeared, thanks to the local Red Cross charity ladies under Lady Marwick. I was introduced to Dr Goldie, Director of Medical Services who told me there was accommodation arranged for me at the Government Hospital and for the medical staff at one of the schools. Seventy-five percent of the Gordons had already arrived, together with 60% of freight and vehicles. Two companies were deployed to Manzini, one to Havelock mine and the HQ coy was to be situated in Mbabane. An advance party of the Loyals had arrived in Nairobi.

The Kenya African National Union [KANU] Head Quarters indicated that they were appalled at the British Government using Kenya as a base for troops to be sent to 'oppress our brothers in Swaziland'. They were unhappy about the slow progress (influenced by the Verwoerd regime in South Africa), in granting independence to Swaziland, Bechuanaland [now Botswana] and Basutoland [now Lesotho] which they regarded as an affront to Africa, and especially to Kenya's self-governing status. They demanded plans for the removal of the British Military Base in Nairobi.

After my arrival Dr Goldie took me to Mbabane on an advanced recce of the Trade School and St Mark's School, the police HQ and the Operations HQ, whilst my party waited at the airport. Fortunately the road between Mbabane, the airport, and Manzini was tarred. The dirt road started just beyond Mbabane and continued half way to Johannesburg. All other roads in Swaziland were dirt and deteriorated in wet weather. We then visited the Government Hospital in Mbabane where I was introduced to the Superintendent, Dr Alexander, who kindly offered to keep my revolver in the safe. I saw a case of smallpox there, so we couldn't have our Casualty Clearing Post[CCP] installed immediately. St. Mark's School was chosen as more suitable for the Gordons' Regimental Aid Post [RAP] under Capt. Martin Cameron, RAMC.

I was advised that our ¼ ton Land Rover with trailer had arrived, but with no driver or keys. It turned out that Pte Mc-Ilwine had been taken off Chalk III as it was postponed. Having fallen asleep, he missed the departure, and had to come on the next Chalk.

In the afternoon the medical orderlies arrived at the hospital; their first job was to chop wood, as the hospital workers were still on strike. In the rapidly cooling, cloudless and windless evening, I attended a press cocktail party at the Gordons. mess at a flat in Queensgate and afterwards had dinner with Matron Baily and her sister, Ms Pat O.Shea, chief radiographer and our 'care giver' to be.

Next day, Sunday, I was moved from an old house, used by the sisters as a mess, to a bungalow next door to the Matron overlooking the main road. Cpl Draper was appointed as my batman, but I don't recall seeing him again on site. Driver McIlwine was given my previous room behind the hospital.

The inspection at 09:00 revealed that most of Sgt Forsyth's party had arrived at the hospital with their equipment except kit bags. We waited for the rest of the party to arrive from the airport. The hospital had 6 beds for Europeans; there was an X-Ray department, a theatre and a well-stocked pharmacy; the pathology laboratory was situated in town. Two medics were deployed to assist in X-Ray and two in theatre.

On Monday 21st, the airport party (and the kitbags) with the second Landrover and driver Ryan arrived to complete our unit, which included 2 200kg of tentage and 130 kg of medical equipment. He had arrived the day before, but the disposition of the Field Ambulance section was not yet known.

I visited Mr Gibbon the pharmacist, and Mrs Gibbon at the pathology laboratory in town. On returning I found that the maids had returned to work so my meals from the hospital kitchen were to be served at the flat. It was to be hoped that my section could move into the new, but empty, casualty building by the next day, since only electricity and water needed to be turned on. Their sleeping accommodation was in due course to be in the almost completed new nurse's home.

Meanwhile, at the Royal Kraal in Lobombo, there had been a big meeting of the Swazi National Council with King Sobhuza in the chair. He had told the strikers to go back to work, although a large number of 'strikers' were not in employment.

On Tuesday, 18th I resisted the Gordons' suggestion of moving my section to Manzini, some 30km beyond the airport, because I found an officer there with possible German measles. Back in Mbabane there was one case of gonorrhoea to see. I was asked to give an anaesthetic for a civilian patient with a sarcoma of the arm which required amputation. He had become very anaemic, so before the operation he required 2 units of blood. This was done by blood typing the client - 'A' negative - and finding two 'O' group donors from the section. After the transfusion Dr Tate did the anaesthesia and I assisted at the operation which was successful. Meanwhile there had been unseasonal rain again.

At 22:00 I was contacted by Ms O'Shea to say that the Pharmacy supply vehicle had not returned from the Komati River road, probably due to its bad state. We travelled in her car and found that their vehicle had slid off the road into the mud along with two others. It was 03:00 by the time we got back,to learn that my OC, Col Robinson, was expected later the same morning.

On Wednesday morning, 19th, I was at the airport to meet Brig Jones. The plane hadnot arrived, so we had lunch in Manzini where I had my first ever, and most delicious, prawns piripiri. I was also introduced to Mrs Brown of the Red Cross, who asked if we couldn't lay on a marquee and demonstration for the Red Cross at the upcoming Swaziland Show.

By now the water and electricity had been connected in the still empty new nurses' home and Dr Goldie gave permission for B Section to be accommodated there.

After my colonel arrived, we were taken to Manzini and given a briefing on the casevac pipeline, learning that the RAF medical officer in Salisbury was likely to be withdrawn back to Aden. We installed the colonel at the Tavern Hotel in central Mbabane.

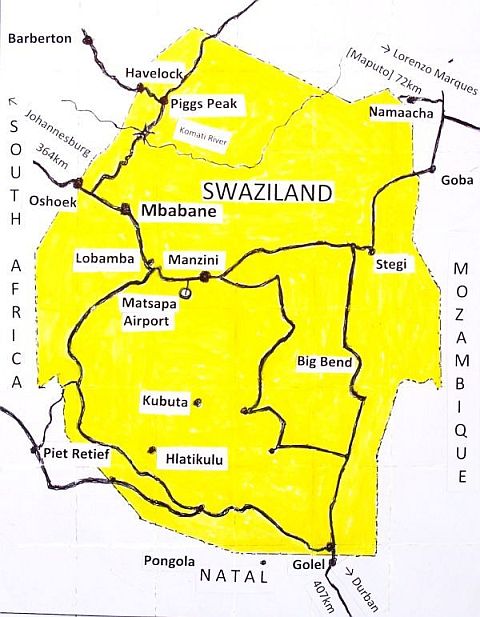

Map of Swaziland in 1963.

Now Eswatini

On Thursday morning [20th] we visited the hospital where I met the Gordons' MO, Capt. Martin Cameron. We were then introduced to the hospital and pharmacy staff and were shown the X-Ray and theatre facilities. There were 6 empty beds reserved for European patients. Next, I heard that Cpl Ryan's Land Rover hood and trailer tarpaulin and some other equipment were still missing.

Unlike Kuwait in 1961, where the enemy turned out to be heat - we had one death and one near death from heat stroke, with a few cases of heat exhaustion - the enemy in Swaziland was infection. There were five main diseases. Typhoid, against which personnel had been vaccinated routinely; unboiled water was to be avoided other than in town. Similarly, smallpox was not a problem. Malaria and bilharzia were prevalent in the lowveldt near the Mozambique border. The biggest problem was venereal disease which had a high prevalence in the local population. Resistant strains had emerged due to the wholesale misuse of antibiotics. I sent a signal to Nairobi for a thousand condoms, which caused some consternation amongst Nairobi wives.

We were informed of an impending inspection by Col Napier, CO of the Gordons; although there were several alarms, this never happened. Instead, after yet another cancellation, I invited others to inspect us, including the Matron and Dr Tate. The next day, Friday, I saw Col Robinson off to the airport after a briefing about the casevac pipeline that I had organised myself. He seemed satisfied with the medical set-up in Swaziland. My initial room at the hospital was now the section common room, of which he also approved. He also suggested that I visit the remoter areas of trouble. But by this time the unrest in Swaziland had died down; we were never subjected to any disturbance.

The 'Jocks' chose the Highland View Hotel for their off-duty entertainment. They made everybody happy, dancing with old and young, married and single, ugly or otherwise. They were well behaved and only required the MPs to collect stragglers after midnight. On the other hand, I had a complaint from the Matron about soldiers accosting African girls in locations and even knocking on their doors.

On Saturday 22nd, after providing two 'O' Group blood donor volunteers for theatre, I visited Havelock Mine near the NW border, which required negotiating the Komati River, reached by hairpin bends, then up via Pigg's Peak to the asbestos mine. There was a sergeant and two of our medical orderlies there; other patients were being seen by a Dr Harrison at the end of the sick parade. I was able to watch the 'Jocks' playing football against a mine team. It was dangerous to allow the ball to be kicked to one side as the ball would disappear down into the valley. Along the road to Barberton in South Africa it was found that there was no border control. In the evening, back at Mbabane, the lurid sunset was enhanced by grass fires in the surrounding hills - Swaziland's annual custom for ensuring fresh green grass for their herds.

On Monday morning, 24th I saw a patient with 'haemoptysis' (possible TB) and then several others arrived until the penny dropped and saved them from having chest X-Rays - they were scratching the back of their throats in an effort to be evacuated to Nairobi. It was later necessary to get rid of three RASC drivers, potential trouble makers. In the afternoon I visited Dr Hine at the leper colony in Pine Valley and returned in time to see the Gordons' Pipes and Drums march through the town, watched by almost the entire population. At the flat my maid, Margaret Dube, was weeping as she expected to be fired for being in the strike - she was later absolved. Waterloo Day had been celebrated that evening in The Tavern, but in the absence of any of the Greys, who had supported the Gordons into that battle.

On Wednesday 26th I was asked to accompany a hypertension patient by ambulance to Johannesburg for urgent treatment, and requested Dr Cameron to cover for me. In Johannesburg I met the eye specialist, Dr Frampton, and then Dr Kemp at the Forensic Pathology Laboratory, as well as taking a trip up the Brixton Tower. Next day we collected our Dr Armstrong after his gastrectomy. HQ complained that they had not been informed of my absence. They also complained that I didn't accede to sending a stretcher Land Rover all the way to Havelock despite the opinion of my sergeant there that it would be unnecessary; I got a strict letter from Col Napier.

On 13th of July, at the Swaziland Show, as requested by Mrs Brown of the Red Cross, we put up our marquee with a walk-through demonstration of mock wounded patients, which our men had been trained to do - as well as to erect tentage in record time. The exhibits were very convincing, displaying such traumas as missing limbs, shock and burns. Two Swazi ladies came out in tears asking how this could have happened to the poor soldiers. At the exit we asked any local European if they would consent (assuming they had a telephone) to being an on-the-hoof blood donor; from those who agreed we then took pin-prick blood samples on a Danish Eldon Card. I discovered that I was A+.

We did not have much contact with the Swazi population at a social level, although they were always extremely polite, according to custom. In return for the great assistance we received I did several clinics for the hospital in remote areas and several times at the prison where the mental patients, male and female, were also kept. At the first country clinic I struggled through the sick parade with an interpreter. When thought I'd finished the sister told me that there were still three dental cases and produced a rusted dental needle, a bottle of local anaesthetic, and a few equally rusty dental forceps. The only treatment for carious teeth was to yank 'em out, although some were so rotten that it was almost impossible not to break them in the process. After a lot of huffing and puffing I managed to remove the offending rotten teeth.

Shortly afterwards an army dentist, Maj. George Smith, arrived and set up shop in the hospital, available to all- comers. I thought this was an excellent opportunity to learn how to do an extraction properly. George kindly demonstrated on three patients and managed to break two out of three teeth!

The Matsapa Airport lies on a flat plain

between rolling hills.

The runway is in the centre third of the photograph

reaching from the lower left towards the upper right.

The buildings are clustered at the closer end.

We only had one death and one severe injury in our unit. Two RASC drivers were taking a 3-ton lorry with no brakes from Havelock to Mbabane for repairs. On the way down to the Komati River they lost control and, missing the bridge, ended up in the river. The driver died and his companion, Cpl Owen, had a high fractured femur. He was air-lifted via Pigg's Peak racecourse (previously an earmarked emergency landing ground) to Mbabane. There was a delay of 3 days in arranging air casevac to Salisbury, despite this being a priority 1 case! The nearest Orthopaedic centre was in Johannesburg, 226 miles away, 6 hours travel by ambulance, half over dirt roads. When the casevac plane was eventually on its way to Salisbury, the patient developed a pulmonary embolism, not an uncommon complication at that stage of the injury. He was severely ill, not fit to go through to Nairobi and had to be taken off and treated in Salisbury at the Alexander Fleming Hospital. He eventually made a good recovery.

One evening, with others, I was invited to dine at the home of the Resident Commissioner, Sir Brian and Lady Marwick. Having no complete civilian outfit I was obliged to go in Battle dress. Nothing memorable happened; everybody was on their best behaviour. I invested in some civvies thereafter.

Our troops in Swaziland were relieved three months after their arrival by the Loyal Regiment who in turn were replaced by the Cameronians, followed by the Gloucestershire Regiment, so that the army remained in Swaziland for ten years until Independence.

A proper barracks had been built for them at Matsapa, close to the airport. I doubt if they were lucky enough to have had the enormous hospitality we had enjoyed from the start of our 'invasion'.

About the Author

Prof (Ret.d) Ian Copley has written several articles for the Journal and delivered several face-to-face lectures.

Ian was Chairman of the Society from April 1990 to April 1992.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org