The South African

The South African

Introduction

The South African War (Anglo-BoerWar) of 1899-1902 took place between the British and the Boer Republics of Orange Free State and Transvaal.

Both sides were supported by various internationals, including Dutch, German, Irish and Russian, but also by local black and Coloured inhabitants as well. Earlier narratives that this was only a 'white man's war' have been proved incorrect.

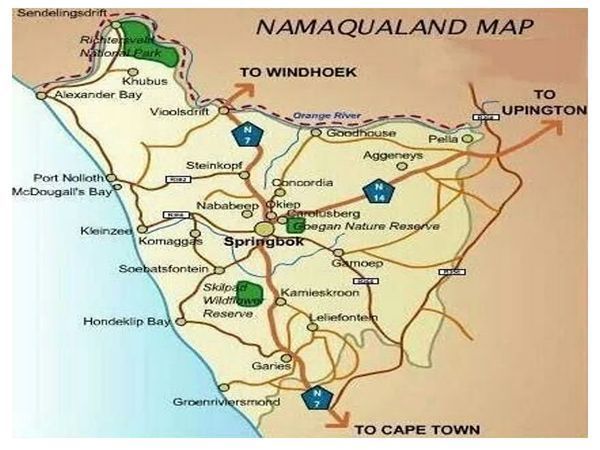

This paper focuses on the research and re-interpretation of an historical event that took place - far away from the two Boer republics - around 04 April 1902, during the guerrilla phase of the war in Concordia, Namaqualand, then in the Cape Colony.

Map of Namaqualand

The story redefines the years of shame for a largely Coloured community, and their descendants, after the Town Guard, under British military command, defied an order to march to protect O'Okiep, a neighbouring copper mining town. O'Okiep was subsequently placed under siege by the Boers for a month and all mining activities were suspended.

Following the military order would have resulted in the Town Guard leaving their families, homes, mine and town unprotected.

Later, the Town Guard surrendered to General Jan Smuts, commanding the Boer forces, without firing a shot, further deepening the view of the British Commander that they were cowards.

Concordia, Namaqualand, taken from the west circa 1902.

This paper also describes how the research and reinterpretation involved the local Coloured community and how this resulted in the erection of a monument to their forefathers, in memory of their conviction. In academic circles, this is regarded as 'engaged scholarship', whereby academics make their research accessible and meaningful through engaging with the communities where their research is undertaken.

Part I

Investigating the past:

Defence of Namaqualand

The formerly rich copper mining region of Namaqualand lies to the north of Cape Town and just south of the South African/Namibian border in a semi-desert region. The main economy of the region at the time of the historical event was copper mining and farming. The mining of copper led to a limited number of settlements being established close to local water sources to support these economic activities, although the first copper-mining town, Springbokfontein, [known today as Springbok], remained as the administrative capital and seat of the Resident Magistrate.

After several commandos under General Smuts entered the Cape Colony, Lt-Col Shelton, East Surrey Regiment, was summoned by Lord Milner to the Cape Parliament and ordered to set up defences in Namaqualand to protect the copper mines.

Shelton chose the largest copper mining town in the region, O'Okiep, as his headquarters, which he fortified with an inner and outer line of defences, using local Cape Copper Company labour and the expertise of Major Leslie Dean, the Cape Copper Company's Superintendent.

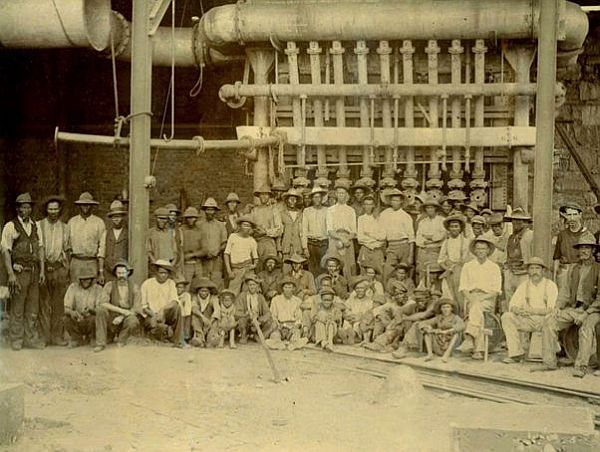

Concordia, Namaqualand, miners circa 1900.

The copper deposit was known to Cape Governor

Simon van der Stel as early as 1685.

By 1856 there was already an operating mine.

The last copper mine closed in 1998.

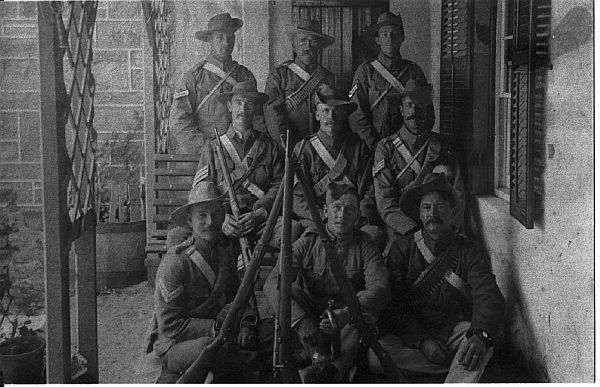

As Shelton only had a limited number of regular soldiers, including both infantry and gunners, he arranged with the Cape Copper Company to train their staff as avolunteer Town Guard. The senior White company and civilian staff filled the officer and non-commissioned officer roles, whilst the miners and Coloured men filled the lower ranks. Initially each town had its own Town Guard; however, these were later amalgamated into the Namaqualand Town Guard.

Those who could ride and shoot, and knew the local environment, were arranged into the 1st Namaqualand Border Scouts while the 2nd Namaqualand Border Scouts were a dismounted unit who protected the railway line to Port Nolloth.

The same principles were applied at Concordia (managed by the Namaqua Copper Company), at Nababeep (yet another mining town), at Springbokfontein, the administrative capital, at Garies, and at the coastal town of Port Nolloth.

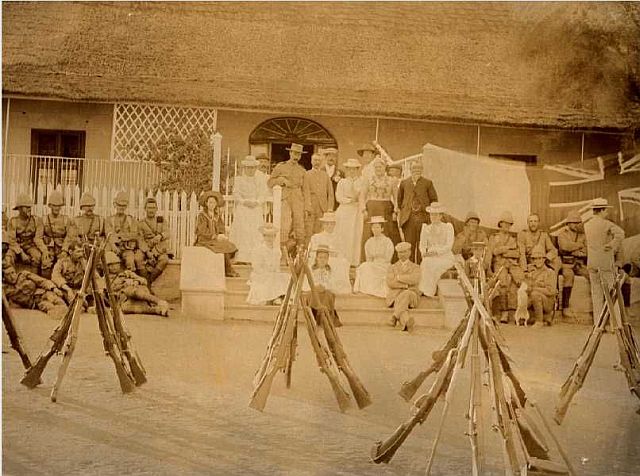

British troops outside Capt. Phillip’s home in Concordia, Namaqualand circa 1904

Blockhouses, built of sandbags and readily available local rock, were built in strategic positions, while other defence works were constructed to guard the approaches to the town, and roads within it. A communication system was established and military stores allocated.

The Town Guards received rudimentary training in drill (for discipline) and shooting - although very few rounds of ammunition were expended on shooting practice. The men were allocated to defence positions under officers and non-commissioned officers.

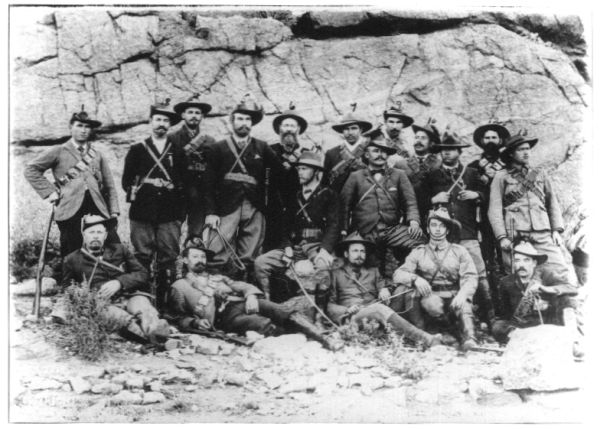

Sergeants & Corporals of a Detachment

of the Namaqualand Town Guard.

Shelton's defence tactics were to send out mounted Namaqualand Border Scouts patrols, with instructions to scout for Boer activity, but not to engage with them, since the scouting patrols were small and few in number.

Colonel White was dispatched towards Garies with a substantial patrol, but was cut off by the Boers and was thus unable to play a role in supporting Shelton at O'Okiep.

As the Boers moved closer to O'Okiep and engaged various detachments in the settlements, or with piquets, so Shelton withdrew his soldiers, rifles, ammunition and military stores from surrounding localities and positions in anticipation of a siege at O'Okiep. With this withdrawal, those who had not hitherto left their farms or towns flowed into O'Okiep in search of safety and security under British protection.

Generals Smuts' and van Deventer's commandos had travelled through the Cape Colony to within sight of Cape Town before turning towards the north. The commandos lived off the land, receiving assistance from friendly farmers and recruiting Cape Rebels en route to swell their numbers.

Generals Smuts, Maritz, van Deventer and

staff at Springbokfontein, Namaqualand 1902

Several skirmishes and battles were fought as they came north. The most notable encounters were at Windhoek, near Van Ryn's Dorp, at Lieliefontein, Garies, Groot Kau (to east of Springbokfontein) and at Springbokfontein itself.

At Lieliefontein, a Methodist Mission Station, the Coloured men initially chased General Maritz out of the town (and killed several of his men) after he had read a proclamation. But Maritz returned with a larger force and killed many of the town's folk, destroying their homes, crops and livestock. The story of this event reached the copper towns and instilled fear in the locals, while General Smuts was said to be very unhappy with Maritz and his commando's conduct at Lieliefontein.

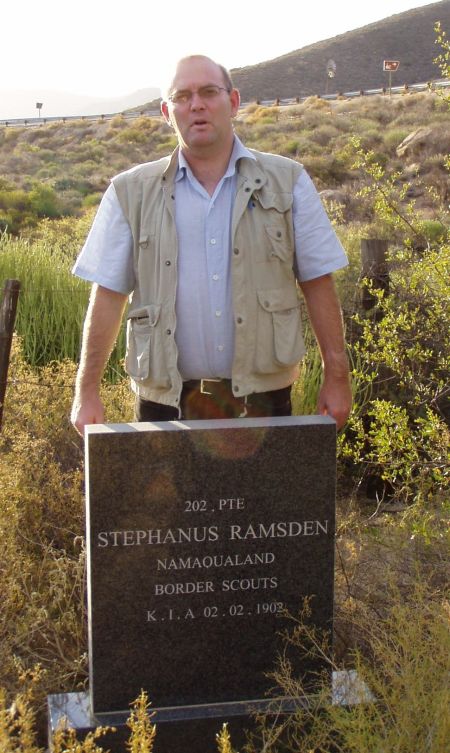

Prior to the fall of Springbokfontein on 01 April 1902, a Namaqualand Border Scout, Stephanus Ramsden, was captured at the farm Naries, to the west of Springbokfontein, while he was dressed in civilian clothes, but carrying a message sewn into his collar. He was taken by the Boer patrol to Spektakel Pass and executed. His body, found many days later where he fell, was examined by District Surgeon Dr Cowan. Ramsden was buried where he fell, and a case of murder opened.

Erecting a headstone and arranging a Christian burial with the owner of the Naries farm, Danny de Wit, was the first memorialisation which this author undertook in Namaqualand. The project, which took four years to complete, involved research, locating Ramsden's grave, and working with a local teacher from Steinkopf to set up a suitable memorial event.

The unveiling of the headstone included local dignitaries, Steinkopf High School Choir and - most importantly - resulted in a family gathering of all the Ramsden family from as far away as Cape Town. Having the school choir present as well as children from the Ramsden family ensured in the event would be remembered by the next generation. The service was conducted by the local priest from Komaggas, the town in which the Ramsden family lived when he was killed.

After consultation with Dr Garth Benneyworth, current Head of the Sol Plaatje Heritage Studies Department, the inscription on the granite headstone reflected the same details which would have been attributed to Ramsden had the British erected a grave marker in his honour.

Author Lt Cdr Anthony-Glenn von Zeil at

Private Stephanus Ramsden’s grave,

Naries farm, Spektakel, Namaqualand

A commando under General Ben Bouwer also ambushed a British patrol under Lt. William McIntyre at Groot Kau. Ten of the Namaqualand Border Scouts were lost as the patrol prepared to dismount, the remainder of the patrol fleeing. Lt. McIntyre was later caught by Denys Reitz in Springbokfontein. The research on this event, including the names of the ten Namaqualand Border Scouts killed and buried in makeshift graves, has been submitted to the British War Graves Commission, as they still erect memorials when ten or more soldiers have been killed in action.

Thereafter Springbokfontein was attacked and capitulated after only 17 hours, with each of the three blockhouses falling in succession. Two fatalities were suffered at the blockhouse located on the rise over which the old road to the town passed. They were Stewart, and van Coevorden, both shot through the loopholes of the blockhouse by Denys Reitz, at that time serving with General Smuts's Commando. Reitz had crawled into position to the west of the blockhouse, under darkness, and taken shelter behind a quartz ridge. At dawn when he saw movement through the loopholes, he fired, and upon entering the blockhouse later, after the surrender, found both bodies with bullet holes through their heads. Van Coevorden and Stewart (a Clerk to the Resident Magistrate) are buried together close to where they fell.

Once Springbokfontein surrendered, the Boers focussed their attention on Concordia and Nababeep. Shelton had ordered the withdrawal of the small garrisons from both locations, since they would not have been able to hold out against Boer commandos several hundred strong. Nababeep responded by sending their men and families by train to O'Okiep before the Boer Commandos arrived. Leaving Nababeep thus unprotected resulted in the mine being damaged by dynamite and the town, both businesses and houses, being ransacked.

The Concordia contingent (nos. 5 and8 of the Namaqualand Town Guard) had also been ordered to bring their arms andammunition into O'Okiep. An ammunition wagon and a small escort did leave Concordia and arrived safely in O'Okiep, but the members of the escort were then cut off from returning home and so were assigned to defensive positions within O'Okiep.

The remainder of the Concordia contingent stood firm, and their CO, Capt Francis Phillips, indicated to Lieutenant-Colonel Shelton that the men would not leave their families, homes and mine unprotected, despite most rifles, ammunition and stores already having been sent to O'Okiep. This defiant response was not well received by Shelton and his officers.

The Concordia contingent remained in their blockhouses and at their defence positions. A Boer commando led by General Smuts arrived at Concordia. Unbeknown to the Concordia Town Guard, Smuts's party was on a scouting patrol, and numbered only about 40 Boers. Smuts took a gamble and called on Captain Phillips and his men to surrender.

While considering their course of action the officers and men of the Concordia Town Guard took the following into account:

Captain Phillips and General Smuts negotiated a surrender, whereby the men, families, homes and mine would not be harmed during Boer occupation. General Smuts agreed and ensured that whilst the town of Concordia was occupied by the Boers that the agreement, a 'state of peace', was upheld.

This agreement between (in effect) the Concordia Town Guard and General Smuts can be viewed as a victory of negotiation and peaceful settlement over violence and war. That Smuts upheld the agreement also speaks to his integrity.

The Boers moved on to O'Okiep, and besieged it for a month, before re-enforcements arrived by sea through Port Nolloth, and thence by railway to the copper town. Because of the siege, all mining operations had ceased. The women and children were housed in the mine, mine buildings and school room. Food was rationed. Daily Orders communicated military activities as well as the decisions taken in order to regulate activities in the town.

Daily sniping commenced especially from the eastern ridges. The town's single 9-pounder cannon, situated on Fort Shelton, was kept busy shelling these eastern ridges to clear them of snipers. Blockhouses, especially to the north-east of the town, were lost and recaptured as skirmishes took place, especially at night.

Several attempts to take the town were made by the Boers. For instance, after General Smuts and his small entourage (including Denys Reitz) had been recalled to the peace talks at Vereeniging, a train loaded with dynamite was sent into the town.

As is inevitable in war, both soldiers and civilians were killed during the siege. A siege burial ground was established to the south-west of Fort Shelton, the siege headquarters. Those who were killed were buried at low light or at night, the area being partly protected against sniping from the eastern ridges. The siege cemetery contained the bodies of soldiers, civilians and children.

Their headstones were marked by simple rocks placed at the head of the grave. After research in London as well as South Africa, this author provided the Namaqualand Divisional Council with a list of names of soldiers and civilians who were probably buried there. But sadly the list of names on the memorial remains incomplete because the Council failed to take the matter any further.

Namakwa District Municipality plaque at the

Siege of Okiep cemetery,

south-south west of Fort Shelton, Okiep, Namaqualand.

Note that the names of the civilian men, women and children

are not included.

Upon the relief of O'Okiep on 4 May 1902, the men of the Concordia contingent were beaten up for being cowards by the 5th Irish Lancers, a British cavalry regiment.

The Concordia CO, Capt. Phillips, an elderly man, was hounded by Shelton and fetched to the Eastern Cape for court martial. It was these Court Martial papers that this author located in the Pretoria archives, and which unveiled the history that Capt. Phillips' family, and the men who would not march, would have preferred forgotten.

Only after the Namaqua Copper Company in the UK, as his employer, intervened on behalf of Capt. Phillips was the court martial dropped.

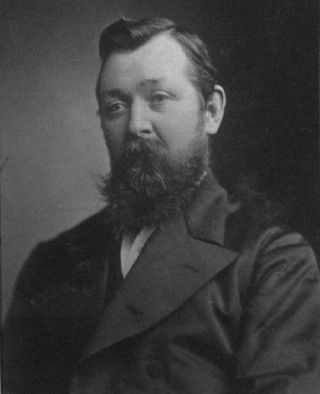

Captain Francis Phillips CO Town Guard

at Springbok and forebear of Dr David Thomas

Part II

In the Present:

Reinterpreting the Past

The author, as a young boy, lived on the diamond and copper mines of Namaqualand.Both his grandfather, Percy Hughes (who in August 1925 had discovered the first economic quantities of diamonds in Namaqualand) and his father, Louis von Zeil, (an accomplished geologist specialising in diamonds) encouraged him to enjoy the veld, walk the battlefields and interpret the environment, both natural and man-made.

Later, as a 15-year-old pupil at Rondebosch Boy's High School, and encouraged by his teacher, Simon Perkin, the author was given the opportunity to participate in the presentation of a local historical topic. The group chose the siege of O'Okiep as its subject. In the course of preparing material the author met Robert Moffat, whose grandmother Jane Henwood had written a diary during the siege of O'Okiep, and whose father had fought the Boers at Anenous and Klipfontein viaducts on the railway line leading to Port Nolloth. This exposure to a myriad of documents and photos further added to the author's passion for the subject.

Since then, he has researched in archives and libraries in South Africa and the United Kingdom, visited many more military sites in Namaqualand, spoken to numerous families, and collected documents, photos, medals, and artefacts.

The Concordia court martial papers were located in a forgotten file in the Pretoria archives. After noting the name of Dr David Thomas, a South African sociologist residing in Australia, in the visitors' book in the Nababeep museum, the author contacted him. He turned out to be a direct descendant of Captain Phillips. Shown the Concordia documents, he revealed that his family had no knowledge of the event - presumably because it was buried as part of a shameful past. The same suppression of memory is evident in the recollections of other Concordia families.

Dr David Thomas, author of

“The Men who would not March”,

at a blockhouse above Tweefontein mine,

to the north of Concordia, Namaqualand.

Dr Thomas wrote a book on the topic, entitled The Men Who Would Not March, based on the author's initial research and on additional material he was able to locate.

This reinterpretation showed that by refusing an order to march the men had bravely decided to stand with their families to protect their homes and mine. The English version of the book went into three editions and it was translated into Afrikaans, Hier was Helde (Here were Heros) for use by schoolchildren as part of their local history syllabus. In 2011, he and the present writer together prepared an academic article with the same title, which was published in the South African Historical Journal in June of that year.

During this process Dr Thomas decided to find a local Namaqualand artist to create an illustration for the cover of his book. He located Ulric Roberts, aka 'Namasun', a well-known local artist, who is community minded, Chairman of the Concordia Arts & Culture Association, and works with local youth. Ulric designed and created the cover and since then has become part of the author's and Dr Thomas' team.

Dr Thomas's book was launched in 2011 in the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Klip Kerk (Dutch Reformed Stone Church) in Concordia, to the delight of the community, who appreciated the re-interpretation of their history. It was after this that Dr Thomas realised that the translation into Afrikaans would be required for the children, to ensure that they could learn the story of their forefathers in their home language.

The group also considered what else might be needed to further embed the revised version of this historical event in the minds of the community and in the physical landscape. A monument to honour the men was deemed appropriate, and Ulric Roberts took charge of this project with enthusiasm and support from the community. He raised finance from local businesses to add to what Dr Thomas himself had contributed. Donations of building material, and most importantly the skills and labour of various local craftsmen, were also procured. It became a true community project, with various players providing direction, materials, and skills.

Ulric designed a monument in the form of a large granite disc which was sourced, donated and cut locally into the shape of a sundial. A quote from Thucydides, an Athenian historian and general, is featured upon it, as wise words to reflect upon: 'The society that separates its scholars from its warriors will have its thinking done by cowards and it's fighting done by fools'.

The monument is reached up a flight of steps.

The Men who would not March

memorial at Concordia, Namaqualand

Around the base of the monument are the names and military numbers of all the men of the 5th & 8th Concordia detachments of the Namaqualand Town Guard. This memorial is thus in their honour and is particularly special since the families of these men still reside in the town.

Initially it was intended to include the names of the over twenty Boers (ten were positively identified in historical sources) who were present at the surrender, as a token of reconciliation. However, when it was discovered that Maritz was amongst them, the community politely declined. It appears that the historical wounds and scars still run deep and have resulted in transgenerational resentment and anger. The "Men Who Would Not March" memorial was unveiled on Freedom Day, 27 April 2017 (an anniversary of the first democratic election in South Africa, of 1994) to the applause of the Concordia community - the direct descendants of "The Men".

Dr Thomas was present as an invited guest to witness the unveiling of the monument, along with various foreign dinitaries. Local youth and children from local schools played an important role in celebrating the day, performing musical and dance entertainments. It was a truly community-centred celebration, bringing out both young and old to remember those men who had chosen their families, homes, and their mine above military instructions.

It was gratifying to see youngsters run up the stairs and excitedly look for their own surnames after Dr Thomas unveiled the monument. The unveiling was aired on national television news that night, and the local community were praised for their initiative. This is probably the only South African War memorial erected in recent times by a local community.

These colour photographs were in the inside front cover of this issue:

Community members crowd around the monument

to the 'Men who would not March'in Concordia,

Namaqualand.

Artisans whose forebears were participants in the Anglo-Boer War incident, and who contributed skills and labour to the monument, admire the finished memorial.

Outcomes

In summary, what have been the positive outcomes of the initiatives which centred around the impact of the South African War in Concordia, Namaqualand?

The future –

Full of possibilities

Conclusion

The fruitful example described in this article of research into, and reinterpretion of, previously established discourse, along with engagement with local communities, should indicate that research and publishing on various South African War topics should definitely continue.

References

Amery, L's. and Childers, E. (Eds),

The Times History of the War in South Africa,

Vol 5, (London, Samson Low, Marston and Co., 1907, pp 538 -555)

Burke, P., The Siege of O'Okiep,

(Bloemfontein, War Museum of the Boer Republics,1995)

De Kersauson de Pennendreff, R., Ek en die Vierkleur,

(Johannesburg, Afrikanse Pers, pp 107 -140)

Ferreira, O.J.O., Memoirs of Gen. Ben Bouwer,

(Pretoria, HSRC, 1980, pp 228 -237,256 -288)

Hibbard, M.G., Boer War Tribute Medals,

(Cape Town, Constantia Classics, 1982, pp 171 -175, Appendix 12)

Kieran M.B., O'Okiep - The Defence and Relief of O'Okiep,

(Bournemouth, Bourne Press, 1995)

Kotze, H.N. & Kotze D.A., Oorlog sonder oorwinning.

Die Anglo-Boereoorlog in die omgewing van Kakamas, Kenhardt, Keimoes

en Upington, (Hermanus, Pastelle, 1999)

Le Riche, P.J., Memoirs on General Ben Bouwer,

(Pretoria, Human Sciences ResearchCouncil, 1980).

Maritz, M., My lewe en my strewe,

(Johannesburg, The Author, 1939, pp 42 -54)

Maurice, F.M. and Grant, M. H., History of the War in

South Africa 1899 -1902, (London,Hurst and Blacket, 1910, pp 453 -474)

McKenzie, A.G., The Dukes . A History of the Duke of

Edinburgh's Own Rifles 1855-1956, (Cape Town, Galvin & Sales, 1956)

Nasson, B., Abraham Esau's War,

(Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1991)

Orpen, N., The Cape Town Highlanders 1885-1970,

(Cape Town, CTH History Committee, 1970, pp 47, 48, 53, 54, 60)

Orpen, N., The Cape Town Highlanders 1885-1985,

(Cape Town, CTH History Committee, 1986)

Orpen, N., The Dukes - A History of the Cape Town Rifle's 'Dukes', (Cape Town, Cape Town Rifles Dukes Regimental Council, 1984)

Ramsden documents, (2001).

Reitz, D., Commando, (Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 1983, pp 298 -325)

Siege of O'Okiep: Siege orders 1902, original document.

Shearing, T. & Shearing D., General Jan Smuts and his long ride, (Sedgefield, The authors, 2000)

Smalberger, J.M., A History of Copper Mining in Namaqualand, (Cape Town, Struik, 1975)

Smuts, J.C., Jan Christian Smuts,

(Cape Town, Cassell, 1952, pp 79 -81)

von Zeil, A-G., "In memory of two fallen comrades, both called Bill", The role of the Duke of Edinburgh's Own Volunteer Rifles in the relief of O'Okiep, Namaqualand, 1902, in the Dukes Dispatch, 2007.

Footnotes

i. Von Zeil, A-G & Thomas, D., in the South

African Historical Journal, June 2011, Vol 63, No 2, p.23.

ii. Kiernan, B., O'Okiep - The Defence and Relief of O'Okiep, Bournemouth, Bourne Press, 1995, p.51.

iii. Thomas, D., The Men who would not March, Cape Town, Print Matters, 2011.

iv. Burke, P., The Siege of O'Okiep,

Bloemfontein, War Museum of the Boer Republics, 1995, p.5.

v. Siege of O'Okiep Siege orders, 1902.

Kiernan, B., O'Okiep - The Defence and Relief of O'Okiep, Bournemouth, Bourne Press, 1995, p.43.

vi. Burke, P., The Siege of O'Okiep,

Bloemfontein, War Museum of the Boer Republics, 1995, p.73.

vii Reitz, D., Commando, Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 1983, p.303.

viii Reitz, D., Commando, Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 1983, p.298.

ix Ramsden documents, 2001.

x. Le Riche, P.J., Memoirs on General Ben Bouwer, Pretoria, Human Sciences Research Council, 1980, p.260.

xi. Reitz, D., Commando, Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 1983, p.305.

xii. Reitz, D., Commando, Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 1983, p.307.

xiii. Reitz, D., Commando, Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 1983, p.305.

xiv. Kiernan, B., O'Okiep - The Defence and Relief of O'Okiep, Bournemouth, Bourne Press, 1995, p.51.

xv. Burke, P., The Siege of O'Okiep,

Bloemfontein, War Museum of the Boer Republics, 1995, p102.

xvi. Von Zeil, A-G & Thomas, D., in the

South African Historical Journal, June 2011, Vol 63, No 2, p.249.

xvii. Reitz, D., Commando, Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 1983, p.316.

xviii. Thomas, D., The Men who would not March, Cape Town, Print Matters, 201,p.148.

About the Author

This will be the fifth article from Antony-Glenn von Zeil to be published in the Military History Journal. The others have been about ships and submarines.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org