The South African

The South African

The capital cities of the Boer republics, Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State and Pretoria in the Transvaal, fell to British forces in April and June 1900. Once occupied, British military traditions of civilised warfare gave them to understand that once an enemy's capital was captured then the war was over. But when the Boers continued the conflict using their farmsteads and women and children to support their commandos there was an angry, bewildered and brutal response. Two years of guerrilla warfare was the result.

Raids were made by the Boers on rail lines, storage depots and supply convoys. British reaction to this campaign of targeting their logistics was for them likewise to target their adversaries' food, ammunition supplies and intelligence. Farmhouses in areas of commando activity were razed to the ground, crops destroyed and stock removed. Boer civilians, women and children, but also old men as well as able-bodied males who had evaded commandeering, were transported to refugee camps. Here they were under the protection of the army who unavoidably took some time to come to terms with providing suitable living conditions for the thousands of people who were swept up.

The very act of concentrating the refugees from the farms diverted the army from their primary objective of combatting the Boer raiders. Just as theBoers had split their forces into small, highly mobile units able to live off the country, so the British needed to evolve tactics to combat this scourge. At first, columns with cavalry, infantry and artillery, ox wagons carrying supplies and camp equipment, with ambulances, farriers and engineers, attempted to corner the men on their Boer ponies who were causing them great anguish. Ponderous columns such as these had almost no chance of cornering their adversaries.

Field-Marshall Lord Roberts left for England once the regular warfare was concluded. He announced, though he made nopublic pronouncement, that the war was practically over and only police action was now required. General Lord Herbert Kitchener took over in December 1900 at a time when Boer activity seemed to be only sporadic. However, Boer forces were still inthe field in numbers and the elusive Free State General Christiaan de Wet was still at large. Both republican governments still operated in the field and a big success at Nooitgedacht in the western Transvaal on 13 December against Major-General Ralph Clements's large column served notice that the war was far from over.

British regular soldiers, many of them, returned to England and India at this time. Kitchener's response was to recruit many more mounted men and use his infantry, those who could not be trained to ride a horse, to protect the railway lines. The new commander needed reinforcements. However, it took time to train fresh men how to ride and care for their horses. In addition to British mounted soldiers, Australian and New Zealand mounted men and their horses were recruited. As they were usually better able to ride and shoot than their British counterparts, most columns had a complement of these men.

Colonial units were recruited in number from the Cape and Natal as well as more uitlanders from Johannesburg. Yeomanry volunteers came from Britain. The Scottish Horse was formed from time-expired colonials who were enrolled anew as well as many Australians who had not been selected for one of their own contingents.

War activity revived as many Boers who had surrendered, signed an oath of allegiance and gone back to their farms, were persuaded that the oath was not binding. They recovered their hidden rifles, mounted their horses and reported for duty. Free State President Marthinus Steyn and General Christiaan de Wet were instrumental in reviving the spirits of their burghers. Within a short period at the end of 1900, in spite of losing men and guns at Doornkraal near Bothaville in November, de Wet was able to assemble a force to invade the Cape Colony. Generals Botha and de la Rey succeeded in motivating their dispirited Transvaal citizens and gathered considerable forces together in the eastern and western districts of the Transvaal.

British mounted soldiers were now organised into columns of varying sizes and composition. Typically a Colonel would command one, or sometimes more, of these columns. Combinations of columns would be brigaded together under a Brigadier-General or a Major-General for large sweeps of the countryside. Commensurate to the effort involved, the returns in prisoners and captured guns and wagons were disappointing. The mobile Boers were easily able to evade the columns sweeping towards them, disperse into small bands, pass through gaps and reassemble once the danger had passed. In the Transvaal, the country becomes more and more rugged further to the east and north; in the west there were vast flat plains. This compounded the operating difficulties of the British, and particularly their logistics.

Stone blockhouses, built to protect bridges or other important points, were built along the railway lines. Smaller and much cheaper little forts were constructed of concentric cylinders of corrugated iron, spaced at 1,000 meter intervals along the railways and extended cross-country so as to divide the country into manageable areas. Barbed wire strung between the blockhouses was not impervious to Boer commandos needing to cross but it was certainly an impediment if a herd of cattle or wagons needed to break through. The blockhouse lines were really only even partly effective in the Free State. In the eastern and western Transvaal different techniques were needed.

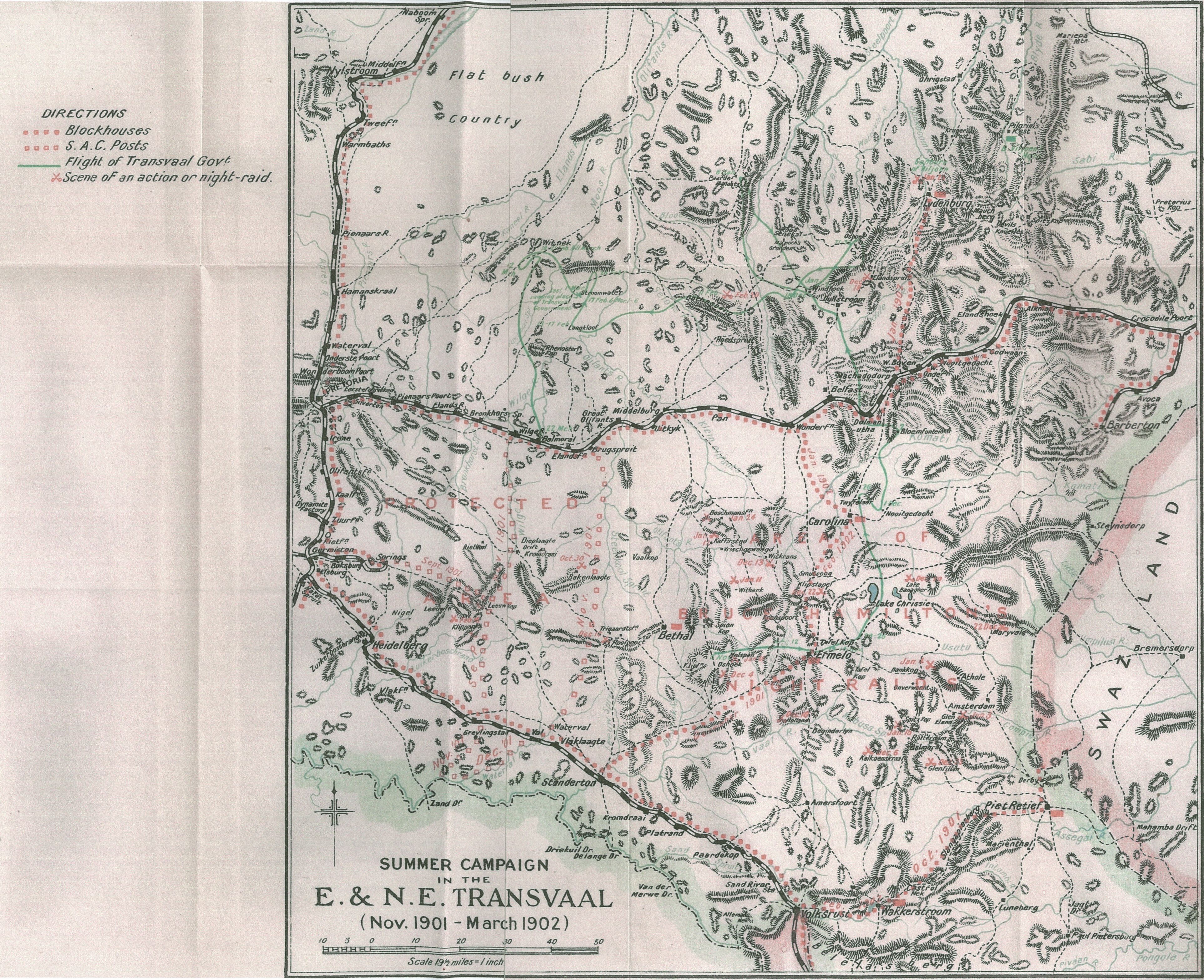

The largest number of Boer commandos was in the eastern Transvaal. South of the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay railway line is the highveld, rolling grasslands but still with lots of places for concealment. North of the line is really rugged country, ideal for guerrilla actions but with not as many targets for disrupting communications or creating supply difficulties. Major-General John French descended on Barberton in September, attacking from the directionof Carolina. By the end of October 1900 the British army had occupied Lydenburg and Komatipoort and had established headquarters in Middelburg. French's much larger operations in January 1901 with a large number of mounted columns in the south east were not productive of the sort of returns that the general officer commanding, Lord Kitchener, was expecting.

MAP - Summer Campaign in the E & NE Transvaal

Enlarged version of map

The railway lines were in British hands but not safe from Boer raiders and there were several breaks in the line over the next few months. The commandos in the eastern Transvaal were numerous and active. Maj-Gen Neville Lyttelton was in Middelburg but unable to stem attacks on the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay line, and seldom moving out of his secure headquarters. Kitchener was not entirely satisfied with the command based on Middelburg. On one occasion, on his way to an interview with Lyttelton, his train journey was interrupted by a Boer attack on Balmoral station.

As a result, Lt-Gen Sir Bindon Blood was brought from India and put in command of the area and what was in effect a division of troops. Blood, a general with a huge reputation from his campaigns in India, was brought to South Africa in view of his experience of fighting against irregular guerrilla opponents.(1) He took command of the whole eastern Transvaal area in April 1901. He must have felt at home in the mountainous terrain to the north and this is where he concentrated at first. He was four years older than Kitchener but now his junior in rank. Placed in command of six columns, they swept up to the north in pursuit of the Transvaal government and General Ben Viljoen who were reported to be at Roos Senekal. By the time thecolumns regained their bases "three weeks of ceaseless activity had resulted in the capture of 1,439 armed Boers, nineguns, 750 rifles, half a million rounds of S.A. ammunition, 964 wagons and carts and nearly 35,000 head of stock".(2) But no Transvaal government and no Ben Viljoen. By the time they had surrounded Roos Senekal it was deserted. Viljoen had a narrow escape, doubling back on himself several times before managing to cross to safety south of the railway.

Another series of sweeps followed, this time south of the railway but on this more open terrain Blood's tactics were no more successful. His 10,000 strong force did not run down even a single Boer leader. Most of the captures were of burghers who were war weary and almost relieved to avail themselves of the opportunity to surrender. Worse, another Indian officer, Maj-Gen Stuart Beatson was responsible for a disaster to the Australian 5th Victorian Mounted Rifles at Wilmansrust, north of Bethal. Cavalry pickets were spaced so widely that, as dusk fell, Commandant Chris Muller's Boers easily slipped inside them and overwhelmed their encampment.

Blood was not the only soldier of his rank in a field command but in the middle of September he returned to India taking Beatson with him. Not much has been written about this very senior general's unproductive stay of five months in SouthAfrica. Blood and Kitchener, his commanding officer, had both risen to high command from the Royal Engineers. His lack of success may have been the cause of some difficulty with his superior.(3)

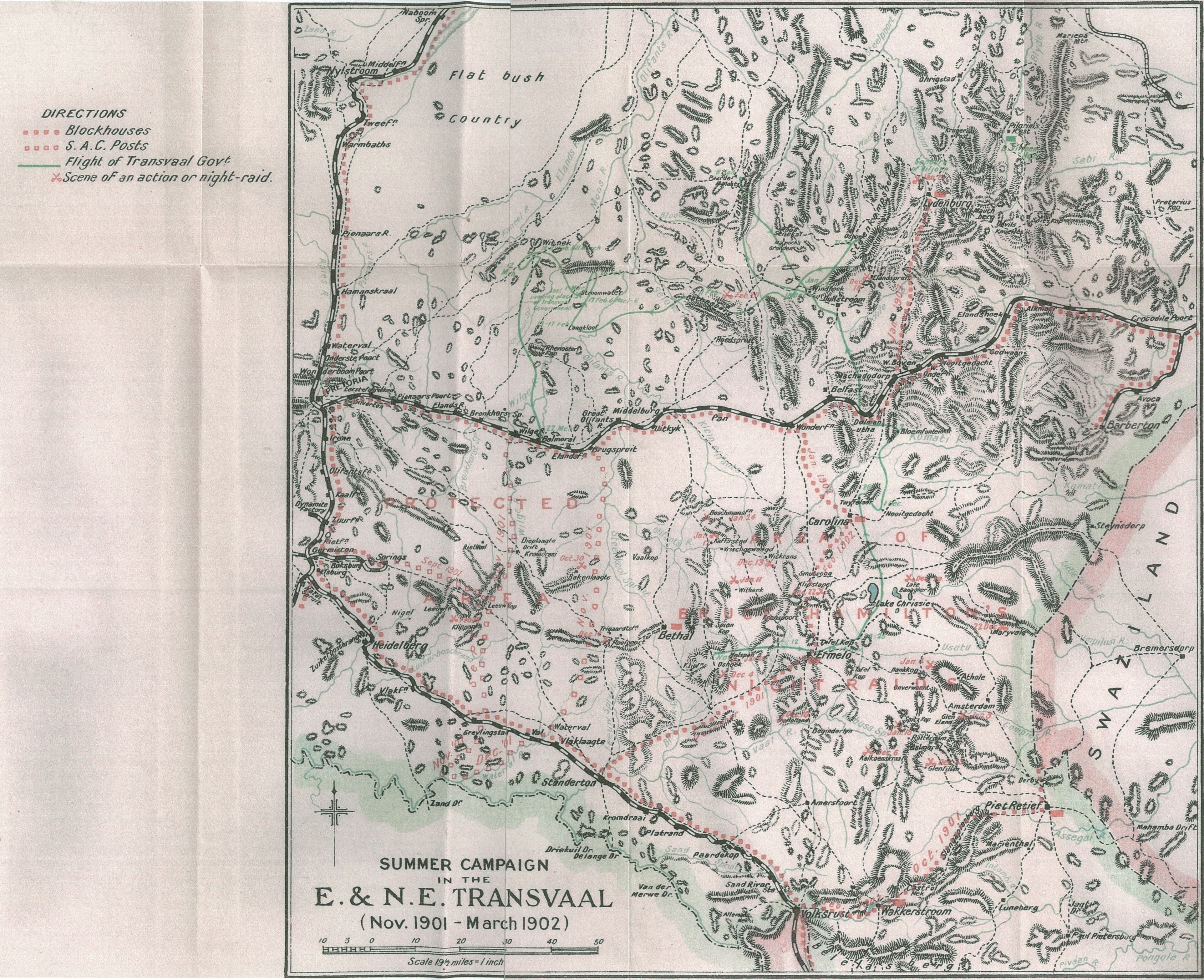

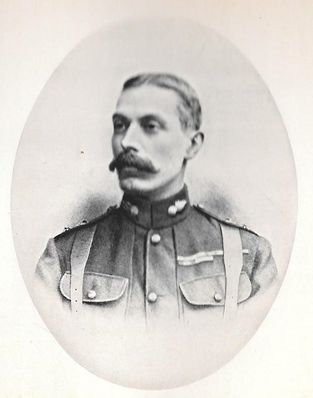

Under Blood's command from May onwards was a young Lieutenant-Colonel, George E. Benson. He was an exponent of night raiding, an innovation that promised great success against the Boer commandos who lived off the land. In the rough country of the north-eastern Transvaal, Benson had limited possibilitiesof using this method of combatting their swift opponents. We also have little knowledge of whether his ideas made any impression on his commanding general.

Benson had arrived in South Africa shortly before war broke out as a Major on special service, tasked with gathering intelligence about the war that was clearly imminent. He acted as guide to the nightmarch of Major-General Andrew Wauchope's Highland Brigade at Magersfontein. Bringing them to the point where they should deploy into open order, the famous warrior general Wauchope ignored his guide's counsel and marched his men still further. The Boers opened fire on the Scottish soldiers as they deployed but now almost at point-blank range.

Benson had long since attracted the attention of the higher command. As an advocate of the use of smokeless ammunition, his presentation at Aldershot in 1894 was to an audience including General Sir Redvers Buller. He stood out in the campaign in the Sudan in 1898 and arrived back to his home in Hexham, Northumberland to a civic reception and the gift of a presentation sword. In the western campaign to relieve Kimberley, Benson was a staff officer with Lord Paul Methuen who was loath to lose him, but Benson was given command of a column early in 1901. Benson's small column (362 mounted menand 515 infantry)(4) had some minor successes in the western Transvaal nominally under the command of Brig-Gen G.G. Cunningham. The high command took note of his methods.

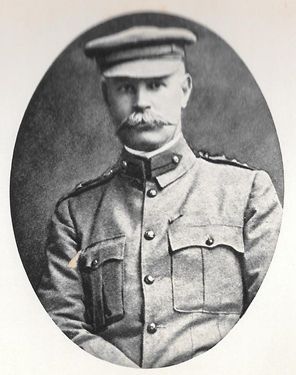

Col. G. E. Benson.

By the second half of 1901 the British army's operations against the Boer commandos in the eastern Transvaal were largely by raiding their laagers at night. Guided by intelligence obtained by African scouts, the troops paraded after dark and then, after a long ride, sometimes as far as sixty or seventy kilometres, would descend on their target just at dawn. The Boers were vulnerable to this tactic and found it very difficult to counter. In May 1901, a young burgher, Roland Schikkerling, reported that 'the enemy is adopting our methods of fighting. At one time it was said that an Englishman was like a chicken. He retires at sunset and nothing may be feared from him after dark. Now, however, he is making night rides all over the country, and practising our own stratagems upon us.'(5)

This tactic was first tried in the western Transvaal by columns under the commandof Maj-Gen James Babington. Colonel Sir Henry Rawlinson's column was directed by intelligence to the farm Goedvooruitzicht in April 1901.(6) Leaving Klerksdorp at midnight, after a 24 kilometre ride, they descended at dawn on the sleeping laager. They captured men, wagons and a 12-pounder gun. Rawlinson at one stagefound himself a prisoner in the hands of his enemy after his horse was shot under him. Without badges of rank, the Boers not aware of his identity, he managed to escape in the confusion. Rawlinson becameone of the leading exponents of this method of attack which the Boers found very difficult to counter.

Once he got to the eastern Transvaal highveld and once Bindon Blood had departed, Benson formed part of a group of columns operating between the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay and the Rand-Natal railway lines. Based in Standerton were columns commanded by soldiers who would attain high command in the Great War. Colonels Sir Henry Rawlinson's, Edmund Allenby's and Lt-Col de Beauvoir de Lisle's columns consisted substantially of mounted men. Another column under Lt-Col St. L. Barter held a fortified position at Boschmanskop, east of Springs.

Benson adapted and developed Rawlinson's method of night raiding. His modus operandi was to assemble a large column with infantry and artillery in addition to the force of mounted men. Supplies were carried in mule wagons but sometimes oxwagons too. His object was for this force to be able to operate at a long distance from their base and to stay out for a week or more. Smaller columns composed solely of mounted men could only be away from base for two or perhaps three days. His infantry and artillery would form afortified camp. The mounted men, informed by intelligence as to the whereabouts of their enemy, undertook raids by night. Excellent intelligence was required, for the tactic could not succeed otherwise. By the month of May Benson was in the eastern Transvaal, based at Middelburg and operating to the south of the Delagoa Bay railway line.

Before setting off on their long night ride the men were given details of their objective. There was to be no smoking or talking and N.C.O.'s took steps to ensure that there was no straggling. Stops were made every hour for the men to rest, close up the ranks and to get water for themselves and their horses. Moving at night meant that the tell-tale dust cloud of the column, which would give away their position in daylight, was invisible. Chewing tobacco was given to the smokers which, in those days, meant almost everyone.

An important aspect of night raiding was that the horses could rest up during the day. They could be fed and groomed and have injuries examined and attended to. The importance of maintaining their mounts in good condition was something that Benson constantly emphasised.

A vital part of the operation was intelligence and this was difficult to achieve without intimate knowledge of the terrain and its inhabitants. By 1901 the British had good maps but these were hardly enough. Local knowledge could really only be obtained from local people. Most British columns used the services of 'joiners', Boers who had gone over to the other side. They ran considerable risk by so doing. If they should be captured by a commando they could expect no mercy.

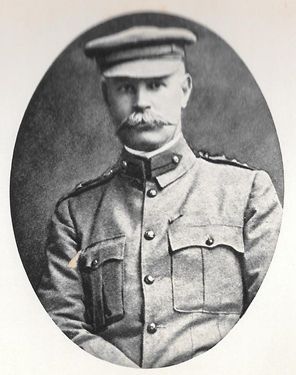

Benson acquired the services of a Johannesburg gentleman, Aubrey Woolls-Sampson. He was involved in the mining industry and had spent most of his life prospecting and setting up mining properties. He was active in the early days of gold mining in Barberton, before the discovery of the fabulously rich Witwatersrand reefs. In the 1890's he spent time in Rhodesia, as it then was, and had interests in a number of mining properties there. He therefore knew the country and its people. He could speak Afrikaans as well as a number of the African languages. He had fought on the British side in the First Anglo Boer War in 1881 and ended up in hospital in Pretoria with Boer General Niklaas Smit in the next bed. In the way of military people they becameclose friends when once it was all over.

Col. Aubrey Woolls-Sampson.

Woolls-Sampson became a memberof the Reform Committee which was organised by the mining magnates to press the government of President Kruger economic reforms. He was caught up in the Jameson Raid, was arrested along with all his fellow Reformers, tried for treason and jailed inPretoria. He had the option of a fine of £5,000 but he and Walter Karri Davies refused, on principle, to pay up. The two spent eighteen months in prison but were released by the President as a goodwill gesture in recognition of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897.

With war looming, Woolls-Sampson, Karri Davies and some others raised a regiment composed of Johannesburg uitlanders with a smattering of Cape and Natal colonials and quite a few Australians, the Imperial Light Horse. This was all done in secret in Pietermaritzburg, paid for, of course, by the mining magnates. Woolls-Samson was given the rank of Lt-Col although under Col Scott Chisholme, previously Commanding Officer of the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers. Karri Davies was ranked as Major and both he and Woolls-Sampson insisted that they would serve for the duration of the war without remuneration or honours.

Woolls-Sampson's career in command of the Imperial Light Horse was unfortunate. Wounded at Elandslaagte, their very first engagement in October 1899, he convalesced in Ladysmith under the conditions of the siege. With an injured hip, even after recovery he had a limp although he could still ride a horse. Unable to participate in his regiment's relief of Mafeking, he only resumed command when they neared Johannesburg. In action he was unreliable and excitable so in January 1901 he was relieved of command and took some months leave to see to his interests in Rhodesia.(7)

A few months later he was back in Johannesburg and looking to join up again. He was given to Lt-Col George Benson as Intelligence Officer and now really came into his own. His knowledge of the terrain ofthe eastern Transvaal, the people and their languages was invaluable. He organised a number of African scouts who were armed and given good horses. Their function was to ride out and make contact with the local people, tribesmen and village dwellers. These country dwellers knew well the whereabouts of the scattered Boer bands.

Benson and Woolls-Sampson formed a very successful partnership. Benson's night raids were almost invariably successful. Woolls-Sampson was employed in Blood's district from April onwards but his general was not able to make full use of his talents until at least some of his columns were fully trained for night raiding. In the dead of winter, now that Benson's column was a reliable force, Woolls-Sampson joined up with this talented guerrilla leader. The column left Wonderfontein on 29 July headed for Carolina and Ermelo.(8) Then came long night marches to Tweefontein and Koppie Alleen where the surprised Boers lost men, wagons and supplies. There was an interruption while he was ordered back east to try and locate a Boer force near Bronkhorstspruit. His raiding resumed after failing to find these Boers.(9)

On 31 August at Kromdraai and around Carolina on September 10, 15 and 16 his incursions "made his column a terror in the district." The biggest capture that Benson made was at Middeldrift on the Mpulusi River on the 18th. Making his way back to Middelburg he took more prisoners, wagons and livestock at Momsen's Store and Driefontein on 28 September and 1 October.(10)

Benson's version of night raiding had been established and he returned back to Middelburg on 12 October to refit his column and also to exchange some of his men for fresh troops from the Middelburg garrison. The eastern Transvaal highveld, in the time of his raids in September and early October was occupied only by those commando members whose horses were not in condition to accompany Botha on his raid to attempt an inroad into Natal. A number of the British columns had moved south, trying to locate Botha's men and drive them back.

Checked at Itala and Fort Prospect, the Boer force retired back towards the Transvaal highveld. They enjoyed a small success when they captured a British supply convoy near Eshowe so that they did not return entirely empty-handed.(11) A numberof British columns sought Botha's commandos which, as per their normal practice, had scattered into smaller units and made their return through the rugged country around Vryheid and Wakkerstroom. Botha himself, the main quarry, was nearly surrounded near Schimmelhoek by the columns of Rawlinson and Rimington. Short of food and cleverly decoyed away from the fleeing general, the British columns returned to Standerton.

Benson and his force were left isolated on the Highveld. Should they have needed assistance, the nearest help was everywhere a day's march away. Around Bethal,Benson ran into a more determined Boer commando than the usual war-weary and dispirited men that they usually encountered. In a running fight both sides suffered casualties and Benson decided to return to his base at Brugsprit on the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay railway. He managed to send a message to Middelburg and thence to Pretoria that he would arrive there on 1 November.

On the night of 29 October the column was camped on the farm Zwakfontein where the column and its transport, tents, field kitchen and horse lines must have had the appearance of a small town. They were sniped at from a distance and may have suffered a few casualties. Next day was a six-hour march to the next camp site, the farm Nooitgedacht. The vanguard must have arrived in mid-morning and set about fortifying the site. The column inevitably became stretched out but this should have occasioned no difficulty except that the weather was misty with some rain. A wagon stuck fast at a stream crossing and had to be abandoned under the fire of Boer snipers.

Botha had assembled and concentrated as many men as he could find in order to eliminate the marked enemy Benson who had become the scourge of the eastern Transvaal Highveld. Botha's men, perhaps as many as 1,200, closed in on the rear-guard of the column and two of its guns. Benson himself arrived with a reinforcement for the beleaguered gunners. A mounted charge by theBoers overran the British force who were more than 2 kilometres from the fortified camp. Benson himself was wounded and sent a runner back to the camp to tell them to shell the ridge, disregarding the presence of the rear-guard, in order to drive away their attackers.

Boer reaction was euphoric at first - the elimination of the man who had caused them to live in fear with their horses saddled up in the early hours of each morning in expectation of a descent on their laager at dawn. Some imagined that here was a prospect of the Boer commandos being left undisturbed on the highveld. This may have been the reaction of a few of the burghers but their generals and commandants knew well that there would be only a short respite.(12)

Kitchener in Pretoria was dismayed at the set-back to one of his best column commanders. A strong column such as Benson's had come to grief at no great distance from Pretoria.(13) Major-General Bruce Hamilton was brought from the Free State and given command of the 10,000 mounted men and infantry on the highveld of the eastern Transvaal. Fresh troops were brought in and Benson's methods were used to assail each and every Boer laager in the area. Hamilton took over the established intelligence system of Woolls-Sampson and his 'joiner', one Lange. Now with a Major General in charge of operations, Hamilton was able to issue orders and coordinate the activities of the several columns in the area.

Hamilton and Woolls-Sampson formed a very effective partnership. Hamilton was ready to take the offensive once he had reorganised the columnsand area command structure. Woolls-Sampson now had his own intelligence staff, a Boer joiner, apparently a man by the name of Lange, and a junior officer whose name seems to have been lost. Additional local African scouts were recruited and trained. Bruce Hamilton's operations in the western Free State had caused the Boers in that area to rejoice when he was sent to the eastern Transvaal.

What happened in the area in December 1901 and up to the end of February 1902 is well told in a letter that he wrote to Lieutenant General Ian Hamilton, Kitchener's Chief of Staff in South Africa.(14) The letter describes the way his columns operated and gives ample praise for the part played by his intelligence chief:

"As a rule, by midday, I would have agood knowledge of the movements of any commandos within reach - we would start the same night - with every available man, and marching all night, led by Woolls-Sampson and his boys, usually found theBoers in their camp quite unprepared in the early morning. When we came in sight of a laager, Woolls-Sampson would grow quite white with excitement - mad to get at the enemy; and on these occasions it may have been no disadvantage that he was with a General of somewhat cooler mould. We had extra-ordinary success: surprising four or five laagers within a fortnight, taking large numbers of prisoners with their camps and belongings, and huge droves of cattle. This went on for many weeks, though naturally the numbers diminished as time went on. I think it is not too much to say that we brokethe Boer resistance in the Eastern Transvaal. I received by telegram the congratulations of H.M. Government and from the Commander-in-Chief at home.

"Woolls-Sampson was a quick-tempered man, but we hit it off from the first. He was always anxious that I should take every available man so as to overwhelm the commandos. This was natural, as our success depended largely on numbers. He told methat he once reported to a certain General under whom he served that the Boers would be at a certain place that night. The General replied: 'Very well, I will send 300 men,' and Woolls-Sampson answered: 'if you only send 300 men I can't go.'

"He always messed alone and spent all his time talking to his boys and thinking what the Boers would do. We were the best of friends throughout, and it was with the greatest regret that I parted from him when he went to your command. (Ian Hamilton is not related to Bruce Hamilton). I hope, my dear General, that this may be what you want. If there is anything further I can tellyou please let me know."

Bruce Hamilton's raids in the eastern Transvaal were usually successful, with some setbacks, particularly at Holland on16 December 1901 and Onverwacht on 4 January 1902. Louis Botha had a number of close encounters but managed to evade capture. By the end of February Botha's commandos had left the eastern Transvaal highveld and moved into the rugged country around Vryheid which at that time was still within the Transvaal. Hamilton's orders were to contain the Boers and not to carry out any aggressive actions as peace negotiations were under way.

Major General Bruce Hamilton's organisation of night raids on Boer laagers was most effective against the guerrilla tactics of the Boers. It needed good intelligence of Boer whereabouts which Colonel Aubrey Woolls-Sampson was able to provide. Hamilton, as a Major General was given command of considerable military force, larger that available to Colonel Benson who preceded him. Hence Hamilton's overwhelming success in clearing the eastern Transvaal highveld of Botha's commandos.

These actions are all mentioned or given full descriptions in Amery The

Times History of The War in South Africa 1899-1902 vol V as well as in Maurice

History of the War in South Africa vol 4.

References

L.S. Amery and Erskine Childers The Times History of

The War in South Africa 1899-1902. Vol V, Sampson, Low, Marston and Company, London 1907.

Winston Churchill The Story of the Malakand Field Force, Longmans,

Green & Co, London 1898 (reprint 29 Books, New York 2004)

George F. Gibson The Story of the Imperial Light Horse in the South

African War 1899-1902, G.G. & Co. Johannesburg 1937.

Albert Grundlingh The Dynamics of Treason, Protea Book House, Pretoria 2006.

Rayne Kruger Goodbye Dolly Gray Cassell & Company Limited, London 1959. Pimlico edition 1996.

Captain Maurice Harold Grant History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902 Vol 4. Hurst and Blackett Ltd, London 1906.

Roland Schikkerling Commando Courageous, Hugh Keartland (Publishers), Johannesburg 1964.

Robin Smith We Rest Here Content privately published, Pietermaritzburg 2013.

Notes

1. As a Lieutenant General, Blood considered that he was not fully utilised in South Africa.

2. Maurice History of the War in South Africa Vol 4 p146.

3 Kruger Goodbye Dolly Gray p417 '...he soon chafed under the younger but senior man's imperious sway.. Childers The Times History of The War in South Africa puts it politely: 'if he can scarcely be said to have bettered his high reputation.. Winston Churchill in The Story of the Malakand Field Force seems to have held him in high esteem - the dedication to his book thanks Major-General Sir Bindon Blood, K.C.B.'for the most valuable and fascinating experience of his life'.

4 Maurice History of the War in South Africa Vol 4 p138.

5 Schikkerling Commando Courageous p207.

6 For some detail of this incident see Maurice History of the War in South Africa Vol 4 p137 and Childers The Times History of The War in South Africa Vol V pp 228-9. There is another account in Gibson The Story of the Imperial Light Horse p288.

7 Gibson The Story of the Imperial Light Horse pp247-255. Woolls-Sampson was relieved of command of the ILH after an engagement at Cyferfontein in the western Transvaal when the ILH lost 15 killed including two officers.

8 Childers The Times History... vol V p330.

9 They may have been the commando of Commandant Joachim Prinsloo and General Piet Viljoen, mostly Heidelbergers who were engaged in encroaching into the protected area east of Johannesburg and Pretoria.

10 Childers The Times History... vol V p331 and p361.

11 No mention of the capture of a convoy in the official history.

12 Accounts of the battle of Bakenlaagte, as it is known, can be found in the two Anglo Boer War histories, Amery vol V pp360-395 and Grant vol 4 pp304-309. A personal account from a diary is to be found in Wilsworth pp31-37.

13 One account says that Kitchener refused food for two days.

14 There were no fewer than five soldiers with the surname Hamilton who were senior army officers in the Anglo BoerWar. Three were brothers, Bruce, Gilbert and Hubert while Ian and Edward were not related to any of their namesakes.

About the Author

Robin Smith is a regular contributor to the Journal. He has written a number of books on Anglo Boer War aspects, some privately printed and others published in the UK.

He lives in Howick, KZN, but he has travelled extensively around South Africa to visit and research relevant battle sites of the conflict.

Robin is a member of the editorial panel and a sub-editor of the Journal. His first article appeared in the June 2004 Journal while this one is his eighteenth!

Return to Journal Index OR Society's

Home page

Maj-Gen. Bruce M Hamilton.

" When we halted at a camp he (Woolls-Sampson) would send off his boys at sundown, each with two horses and told to go to the agent in a certain village, not too far away from them to be able to visit it and return after daylight. Thus next day he would have heard of any Boer commandos within a radius of twenty-five miles from our camp. He would spend hours talking to his boys on their return, encouraging them, cross-questioning them, and checking what they told him. It was dangerous work for the boys, as the Boers killed any they caught and we found their bodies as a warning on the veld. It was due to Woolls-Sampson's unceasing efforts to take care of his boys and gain their confidence, and his great attention to detail that his information was so wonderfully accurate. He had an extraordinary sense of what the Boers were likely to do, and over and over again, after marching all night, we would find them at dawn exactly where he expected.

December 1901 – February 1902

Oshoek 4 December

Kalkoenskrans 6 December

Witkrans 13 December

Holland 16 December

Trigaardsfontein 16 December

Lake Banagher 20 December

Klipstapel 22 December

Maryvale 22 December

Glenfillan 23 December

Glen Eland 3 January

Bankkop / Onverwacht 4 January*

Witbank 11 January

Kafferstad 17 January

Spitzkop 18 January

Boschmansfontein 24 January

Nelspan 26 January

Bothasberg 20 February

*(columns under the command

of Brig Gen H.C.O. Plumer)

All are marked on the Times History map Summer Campaign in the E. and N.E.

Transvaal, which was too detailed to reproduce in the printed Journal.