The South African

The South African

Introduction

In the last six centuries much has been said about this 'outlaw' in tales, ballads, songs and plays and recently he has become the hero in films, usually opposing the Sheriff of Nottingham [a different person elected every two or three years]. Some people regard him as a mere myth or sprite. The Encyclopaedia Britannica of 1952 is dubious; the sudden appearance of the ballads after the fourteenth century 'may have been based on fact'. Nowhere is it commonly known as to why he became an outlaw and how he became particularly famous.

Traditionally he was always God-fearing, kind and generous, without a specific intention of robbing the rich to give to the poor. The ballads show him assisting those in need whether rich or poor.

To have any idea of the real person, one has to go to the earliest ballads before more fabrication or romantic distortions have been added.

In Elizabethan times the earldom of Huntington [lapsed in the 12th century] was accorded to him and the ballad recounts the happy ending of how it was restored; Maid Marion appears as his betrothed. His real wife was called Matilda

In Walter Scott's Ivanhoe he is placed in the time of King Richard and King John, other tales have him as a Saxon against the Norman overlords. However, tales of Robin Hood only appeared after 1377 based on local traditions and ballads. [Holt, 1982, p 115].

He is mentioned as a real person in William Langland's Piers Plowman, Passus V c.1365.

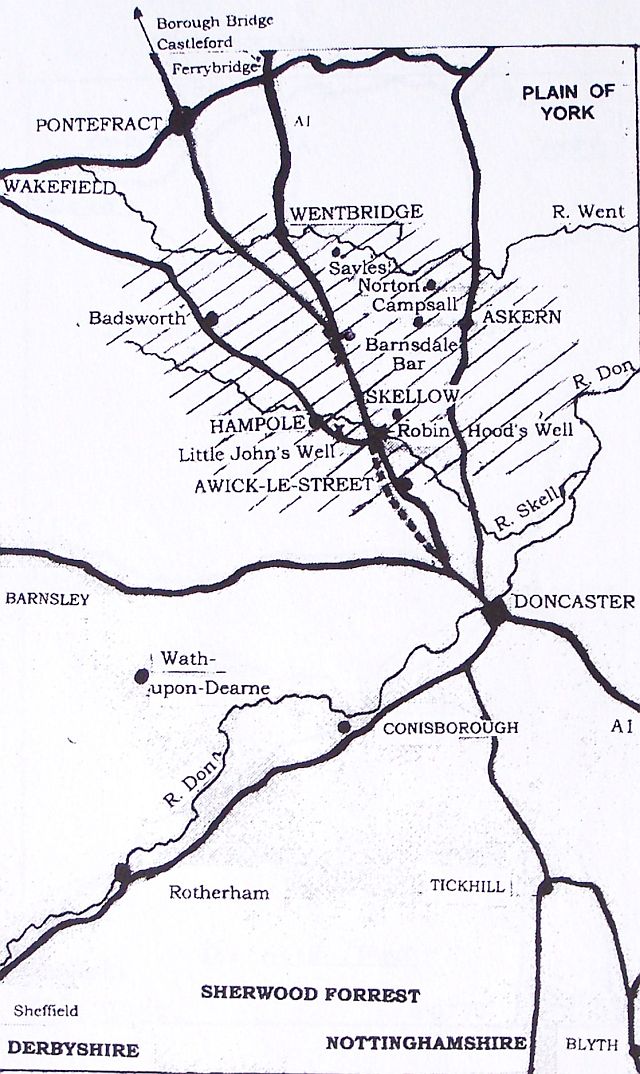

MAP Barnsdale Forrest, South Yorkshire

Broken line – Roman [raised] High way at Adwick-le-Street.

Destroyed at Barnsdale Bar for M1 Motorway

Photo Copley

During the years between 1838 and his death in 1861, Joseph Hunter was Assistant Keeper of the New Public Record Office in London who thus had access to records of medieval government. He noted that a Robyn Hode was temporarily in the service of King Edward II, as to be seen in the Household Accounts, as [in French legal terms, a yeoman or] a 'vadlet de la Chambre'. In the same prior period the name is found in the Manorial Rolls of the Honour of Wakefield in Yorkshire. Robyn Hode, the only resident there of that name, tallies with the name in a collection of early ballads known as 'A Lytell Geste of Robyn Hode'. [Gutch, 1848, Vol 1 p 145 . 219]

Political background -

[See Maddicott, O U P, 1970]

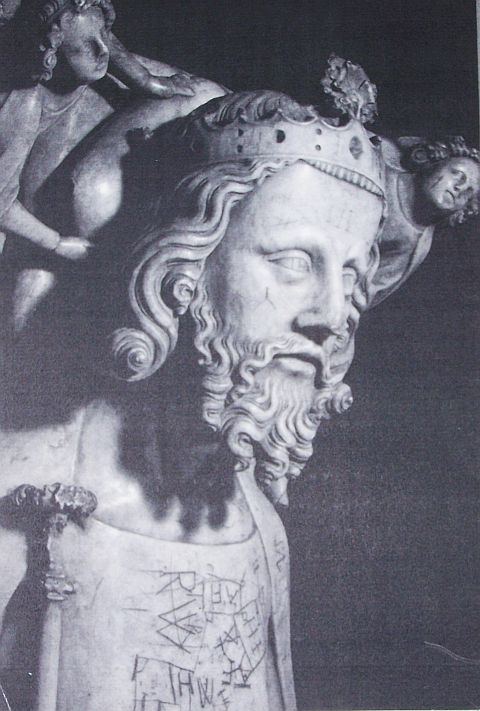

King Edward II [1307 - 1327] was a weak-willed ruler, more interested in pleasure and sport; he was surrounded by influential household officials including the Despencers, father and son and Piers Gaveston having relationships with the latter two. He liked to mix amongst the common people. He was not much of a military man and was defeated at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 by King Robert Bruce of Scotland.

Edward II

Gloucester Cathedral

Photo Copley

Reforming laws of the time made both the king and people subject to Parliament, the only body responsible for the introduction of taxes, laws and policy.

A section of the nobility began to form against the king and his favourites, notably the barons of the Welsh Marches, including his cousin, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, said to be an unpleasant character. Together with his fellow barons he was outlawed leading to the formation of the 'Contrariantes' party against the King.

At a parliamentary gathering in 1321 the barons forced the king to exile the Despencers. In retaliation the King occupied the Welsh Marches whilst Lan- caster had to gather his adherents at Doncaster to make a stand against the king who was moving north towards him. He then retired slowly to his castle at Pontefract.

The inhabitants of Wakefield

The Lytell Gest starts by saying the Robyn was a 'good Yeoman', meaning a free man or commoner. It could also mean that he was a gentleman serving in a royal or noble household ranking between a sergeant and a groom. The Wakefield Manor Court Rolls [Yorkshire. Archaeological Journal Vol xxxvi, p 4-46] mention Robert Hode and his wife, Matilda, and their handmaid several times. In 1316 he bought land and built a house on Bichill becoming tenants of John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey and lord of the manor of Wakefield. [Walker, 1973, p 8]

In 1316, the manor had to provide 200 foot soldiers for the King's army against the Scottish raiders. Robyn was fined 3d for disobeying the muster. The following year there was another muster; he either attended or was not called. His name does not appear at the next one in 1322,but under the circumstance of a large contingent needed, he is more likely to have been called up.

The year 1318 was to be significant in that the ownership of the manor of Wakefield changed hands due to Warenne being involved in the kidnap of Lancaster's wife. In revenge the Duke attacked Earl Warenne's castle at Sandal outside Wakefield. The king condoned his action and granted him the manor of Wakefield. Lancaster also owned the manor of Pontefract [Pontus Fractus]. [Walker ??]

Relations with the King had deteriorated in the following years. His attack on the Marcher lords was unexpected, as was his move northwards.

Lancaster was unwilling to progress beyond Pontefract towards the Scots for fear of being branded a traitor, but was persuaded otherwise at the point of a sword by one of his adherents.

By late 1321 Lancaster had withdrawn to Pontefract from Doncaster with his supporters as the King moved northwards. His two manors of Wakefield and Pontefract were therefore required to provide 2 000 men; 1 000 to be provided with aketons [padded tunics], basinets [a 'tin hat' with visor] and gloves of iron; 1 000 archers with bow and arrow, the likely draft for Robert Hode who would have walked the 10 miles [16 km] to the muster at Pontefract. The final number of men near 700 was more likely to be due to desertion.

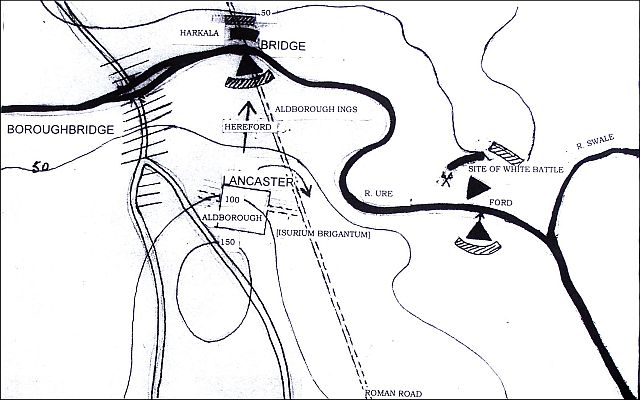

The Battle of Boroughbridge

Isurium Brigantium [Walker, 1973, p 9]

It was not very cheering for Robyn and his fellow mustered townsmen as they walked northwards along the Roman road, in the cold and wet, knowing that their homes and belongings may be subjected to royal vengeance. Lancaster's army reached Boroughbridge on Tuesday, 22nd of March, 1322 and stopped short at Aldborough having learnt that the nearby bridge was already defended by Sir Andrew Harclay who had been at Ripon. He had received instructions from Edward's queen, Isabella, who was very politically active, to headoff the earl's retreat. On hearing the news, Lancaster went to meet him to try and persuade him to join them, but to no avail; Harclay declined to be a traitor.

The Earl of Hereford led Lancaster's attack across the narrow bridge which was in the process of being broken down. He was an early casualty, not from the hail of arrows from the higher ground, but from a Welsh spearman beneath the bridge who stabbed him from below in the vulnerable gap in his armour so that he was mortally wounded, spilling his entrails on the bridge.

Battle of Boroughbridge 16 March, 1322. Archers’ positions striated

Copley

Lancaster then decided to attack the flank via the nearby ford further downstream, but this had been anticipated and the engagement took place on the north bank of the river, only for Lancaster to have his men and archers dominated by the archers on the higher ground beyond. Pike men prevented the use of cavalry, the result being that Lancaster could not relieve his force at the bridge. There was great slaughter as well as losses due to desertion.

At length a truce was observed till the next day on condition that the Earl would fight or surrender. The survivors returned to their lodgings.

During the night Simon Ward, Sheriff of York, who had been alerted by Queen Isabella, arrived and entered the town at first light, with minimal opposition. The Earl declined to yield and fled into the nearby chapel for sanctuary, throwing himself before the altar for God's mercy. Sanctity was ignored; he was stripped of his armour and dressed in the livery of his page. He was then taken by water to York and thence to Pontefract castle where he was the first occupant of the dungeon under his newly built Swillington tower, only accessible by a trap door. He was beheaded after a short trial.

Elsewhere, captured survivors of the battle [traitors] were hung, drawn and quartered; others had the same fate in different places as they tried to flee the country. Robyn and friends had no choice but to flee into the woodland to make their way to Barnsdale Forrest, not far from Wakefield. The adjacent Sherwood Forrest, further south, would not have been suitable as a hiding place, as it was a royal game reserve with officials such as vergers and warreners, whereas Barnsdale Forrest, a noted haunt of robbers, was more densely wooded. The Roman road between London and Edinburgh conveniently ran through it. An armed escort was needed for this section of the road in those times in the event of transferring goods or money, in either direction, on account of footpads.

How or why did Robin become famous?

The ballads concerning the outlaw appear to start in the 14th century

He is always described as courteous and chivalrous as well as devout. It is suggested that he may have served at court or at a noble house previously, since he recognised the King.

Certain names mentioned in the Lytell Geste, the earliest collection of ballads, have been identified, some from Wakefield, but not that of the Sheriff of Nottingham since there were a dozen holders of the office in the next 30 years. One, Henry de Fauconberg, who also appears in the Wakefield Manor Rolls, had the reputation of being very unpleasant, but no one was beheaded as in the Geste [Fytte VI].

Robin had a reputation as a marksman with the newly introduced Welsh long bow and won at a tournament in Nottingham [Fytte V].

A year after the Battle of Boroughbridge, our 'comely Kyng Edward' [Edward II, the only Edward to make a tour of the north of England] came to view his newly acquired properties that had belonged to the traitors.

He was at Nottingham in November 1323 [Fytte VII] and during his tour of parts of the North he had noticed a dearth of his royal deer, said to be due to Robin Hood.Nobody would give away Robin's whereabouts until a royal forester offered to lead the king up the highway to meet with him if he should go to the adjacent abbey and dress up with five others as monks.

They met Robin 'standing by the way' who took hold of the 'abbot's' horse to detain him. The abbot said that he had only 40 pounds left having been recently with the King. Robin took it all and gave half to his men and then returned the other half to the abbot, who then gave Robin a royal summons for him to come to Nottingham. Robin thanked the abbot and insisted that he was a loyal subject. He invited the abbot to dine with him, blew his horn and all his men, 'seven score' appeared, which greatly impressed the abbot.

They dined off royal venison and after dinner an archery match was organised, called Pluck buffet, anyone who missed the target forfeited an arrow and a buffet to hishead. Robin lost once to the abbot and received a buffet that nearly knocked him down and he then realised that this is no ordinary monk. He recognised the king, as did Sir Richard of the Lee who stood next to him [recently rescued by Robin from the Sherriff of Nottingham].

The King then invited Robin to come to court with his men. Robin accepted, but indicated that it would not be permanent. They then rode to Nottingham, 'all dressed in green', to the amazement of the townsfolk.

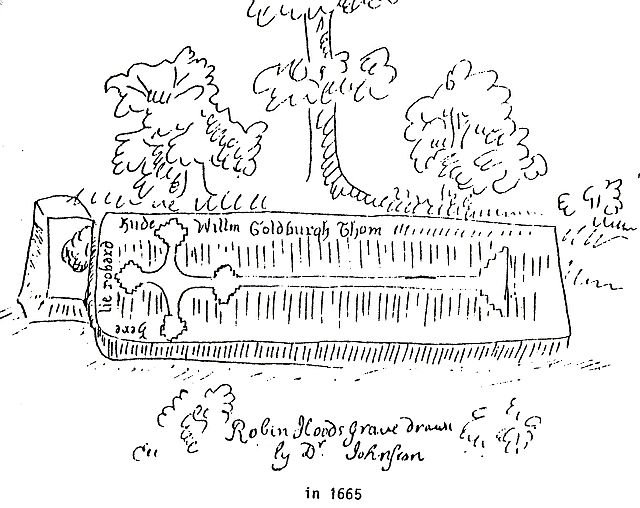

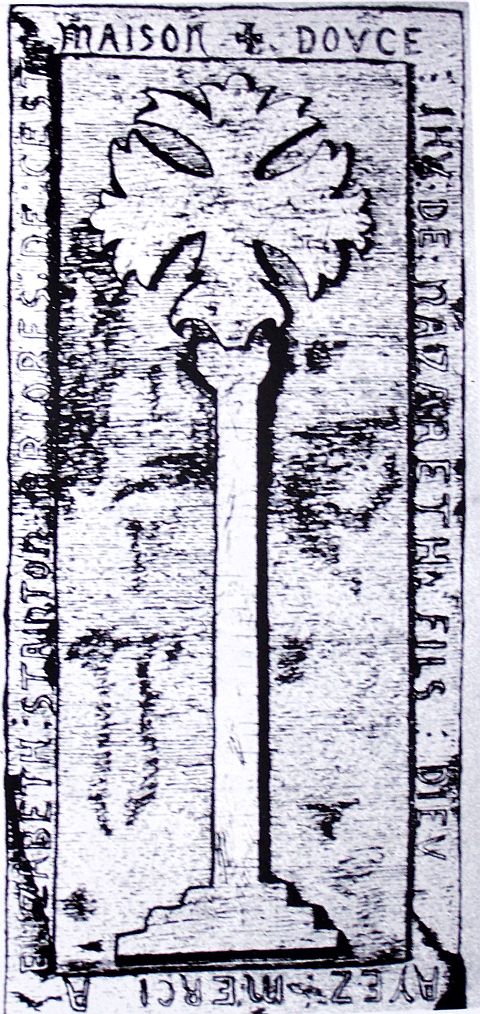

Gravestone at Kirklees [destroyed by Irish

railway navvies as a cure for tooth-ache]

'Robard Hode'... Drawn by Dr Nathanial Johnson in 1665.

Harris, 1971, p 34

Robin stayed at court in London for 'twelve months and three'. [Fytte VIII]

The Household accounts of Edward II include the Journal de la Chambre in which a Robyn Hode appeared in March, 1324 a month after the King had returned to London. He was called a 'portour' with 28 others and paid 3d a day. The numbers of'his men dwindled over the next months. The last entry for Robin's name appeared at the end of November, 1324.

The ballad continues in Fytte VIII saying that only Little John and Scarlet remain with him. He saw some young men shooting at the butts which made him yearn for the greenwood. By this time he was either bored or disgusted with life at the court.

Robin asked the King for leave to do penance at the chapel he [may have] built in Barnsdale. The King gives him leave of seven nights, but Robin never returned from the greenwood where he rejoined his men and carried on as before for the next 'two years and score', thus remaining there into the late 1340s - presumably he and his men had not been pardoned.

I have visited the Public Record Office in London for any sign of a warrant or reward for Robin's capture, without success. It is like looking for a needle in a haystack and not knowing which haystack {is} most likely.

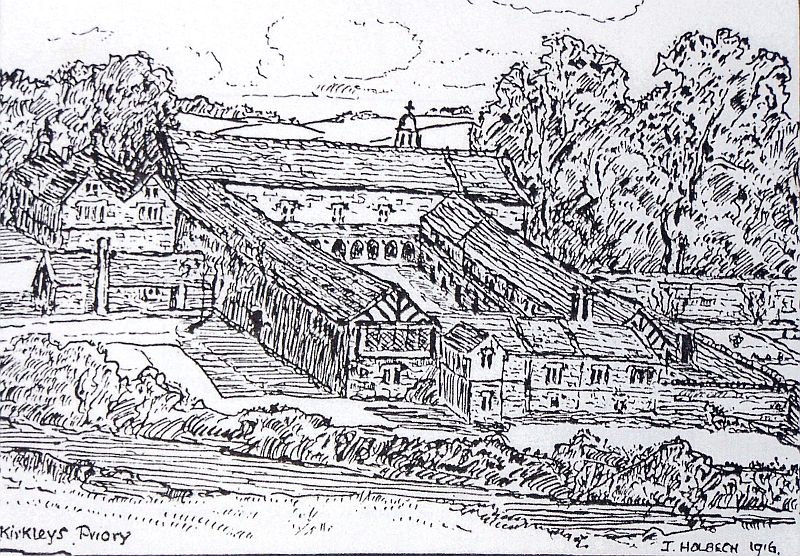

Kirklees Priory - Reconstruction from

pre-dissolution description and excavations

of 1904 – 1908 - drawn by H N Popjoy.

[Speak, 1916, p 27]

Robin grew sick and went for help to the Prioress of Kirklees who was 'nigh of his kin'. This could have been Elizabeth de Staynton of a Wakefield area family, a prioress who may have died c.1350. She had a lover, Sir Roger de Doncaster, a priest. [Women were often assigned to religious houses against their will for many different reasons and thus were not overzealous].

Other accounts say that [using the standard treatment of the time], the abbess bled Robin in excess until he was too weak to defend himself against Sir Roger. It is not known why they conspired to 'betray' Robin unless an [unclaimed] reward was available.

A cross on Calvary gravestone existed similar to that of Elizabeth.

Thus Robin Hood was known as a gentleman who was courteous, kind and generous with a religious outlook. He was an outstanding archer; he had had the honour of being singled out by the King, despite having been on the traitor's side.

Gravestone at Kirklees – Elizabeth de Stainton

‘Gentle Jesus of Nazareth, Son of God, have mercy on

Lizabeth de Stainton, Prioress of this house’.

He had a long life in the greenwood defying authority and had a martyr's type of death at the hands of a 'wicked' woman. He was well known locally in the West Riding of Yorkshire from where the ballads spread throughout the world with many adaptations.

The evidence is circumstantial, but the earliest known accounts accepted by local people, initially oral, match quite well with the contemporary records.

Bibliography

Copley, I B, The significance of the poem King Edward & the Shepherd to the contemporary audience [Pretoria, UNISA Medieval Studies, 1995]

Gutch, J M, A Lytell Geste of Robyn Hode, Vol 1 Fytte 1-8. [London Longman, 1848]

First published/printed [Gothic type] in 1520 - Printer's colophon,

'Explicit, Kyng Edward and Robyn Hode & Lytell Johan, Emprented at London in

Flete Strete at the syn of the sone by Wynken de Worde'.

Harris, P V, The Truth about Robin Hood [London, Self-published, 1971]

Maddicott J R, Thomas of Lancaster [1307-1322], [Oxford University Press, 1970]

Speak H & Forrester J, Robin Hood of Wakefield [Wakefield, Self-published, 1970]

Wakefield Manor Court Rolls [Yorks Arch J Vol 36 p 4-46]

Walker J W, The True History of Robin Hood [Wakefield, E P Publishing, 1973]

About the Author

Ian Copley was born in the West Riding of Yorkshire about half way between where Robin Hood was born in Wakefield and where he died at the Priory of Kirklees near Mirfield that accounted for a lifelong interest.

Previous articles of his have been included in several issues of the Military History Journal.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org