The South African

The South African

Abstract The Punitive Commando

The emigrants were in a crisis after the loss of Piet Retief and his men and the subsequent massacre at Bloukrans on the 17th February, 1838. The other Voortrekker leader, Gerrit Maritz, became increasingly ill and was unable to lead an expedition. The enmity between the leaders are well-known and it was decided that Piet Uys and Hendrik Potgieter would each lead their own men to form a commando in retaliation to the perceived aggression by the Zulus and their king, Dingane kaSenzangakona. The unresolved issue of leadership would have tragic consequences for the Voortrekkers.

Haarhoff revisited the battle-site of Italeni as proposed by C de Wet and found several discrepancies and errors in conventional accounts. The author was able to identify the hillock named Italeni, and the reminiscences of the burghers involved can now fully be explained by the newly proposed site of the encounter. Seven of the ten Voortrekker graves were found which needs further archaeological examination. An expanded version of this article in Afrikaans is on the Society website

For the sake of speed and agility they agreed not to take wagons. Baggage, provisions, and extra ammunition were carried by between 75 to 100 pack horses. Boshof(1) estimated that there were 347 fighting men, roughly split into two commandos.

It is important to calculate the dimensions of such a force and try to envision them at the proposed battle site. If a row of five horses trotted abreast (a width of approximately 12 m) the column would have been ninety horses deep which would total about 350 - 400m.(2)

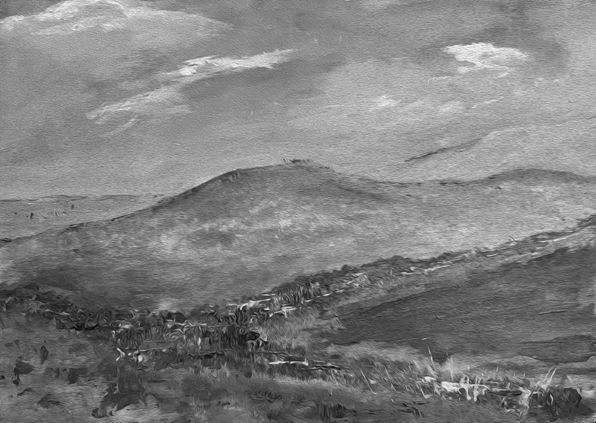

Italeni, where a great battle took place on 11 April 1838.

This small hill is less than three kilometres from

uMgungundlovu. Some of the white shields were visible on

the crest of the hill with the right horn advancing along the

plain on the left of the picture. The left horn was hidden

behind the neck on the right which caused the Voortrekkers

to seriously underestimate the strength of their foe. The

Nzololo stream runs from right to left and the reed creek

meanders diagonally in the painting.

On Friday, 6th April 1838 the commandos left for their rendezvous at Skietdrift. The commando proceeded towards Danskraal, passed Wasbank on 7th April and bivouacked on the Sundays River on the Sunday. They entered Zululand at Rorke's drift, crossing the Buffalo River and continuing along the high ground. They encountered a few Zulus and were aware of a sizeable cohort of fighters retreating in the distance.

The Zulu impis were led by the able tactician, Ndlela kaSompisi and assisted by Nzobo kaSobadli (Dambuza). Ndlela chose his field of battle after careful consideration. Italeni, which stood as a sentinel 3km before uMgungundlovu, was to become the perfect killing ground. He would show the oncoming column only a portion of his Impi and hide the rest from view, ready to pounce. His first goal was not to alarm the Voortrekkers, but to draw them into battle. Once they were committed, he would crush them in the pincer movements of the buffalo horns. (The Voortrekkers were then still unaware of this Zulu battle tactic).

As usual, he placed his veteran warriors, called the white shields, at the centre of the battle. He organised them into three rows at the top of the hill, with only a limited number visible from the low-lying western ridges. Estimates put the white shields at 3 000 warriors and the two black shield horns at 2 000 warriors each. Only the right horn was visible on the plain, and they initially moved slowly forward to avoid alarming the trekkers. The left horn was placed in the gullies and streams behind the neck where they were invisible to the attackers.

Ndlela had set his trap.

The route to the Nzololo stream

It was sunrise on Wednesday, 11th April 1838. The burghers were looking down at uMgungundlovu, barely 6 km away. After a short discussion they decided to take the clearly visible footpath on their left which meanders down the hills to the valley. This road was probably engineered by elephants over centuries, as so many other passes in South Africa(3).

It took them close to two hours to reach the valley floor and the Nzololo stream. When they were about midway, they noticed the white shields on the summit of the sentinel hill called Italeni, sitting placidly on their shields, smoking, and peering at the oncoming column of Voortrekkers. Italeni sloped gently eastwards to form a neck towards the hills on the opposite side of the basin. The left horn lay hidden behind this ridge.

As the burghers descended further down the pass, they saw that the road veered to the left, by-passing Italeni hill and running on the eastern side of the stream. On the eastern side of the basin was another range of hills, and to their right Kataza mountain was slightly obscured by two hills. A creek crossed the basin diagonally from the south-east, meandering at the southern base of Italeni. The lower reaches of the creek were choked with reeds as it joined with the Nzololo stream in front of them. In the distance, towards the north, they noticed a column of Zulus (the right horn) advancing slowly in their direction.

Halting in front of the Nzololo stream they started to deliberate. They were still a thousand metres from the white shields on the summit of Italeni.(4) The leaders again took stock of their immediate surroundings and noticed the deep donga formed by years of torrential rains below the hill on their right. Looking closer to their left (north) they noticed some Zulu gardens. The low-lying ridges right next to them were criss-crossed by gullies and dongas and the Nzololo hugs a small hill slightly further north. A drift was visible three hundred metres downstream from where they conferred, and they noticed that the Zulus were still closing in.

Today, 185 years later, the surroundings look somewhat different. The plantations on the Ntonjaneni heights have altered the vegetation completely. Nico Harris recalls that trees and shrubs have overtaken the grassy terrain during his lifetime. He notes that the Nzololo stream is now vastly more overgrown with trees compared to fifty years ago and lacks running water.(5)

The Ambuscade

It was Potgieter's contention that they should reconnoitre further, as he was weary of an ambush. Piet Uys was keen to attack, and he pressed Potgieter to decide: 'De kaffers(6) zijn in twee kommandos; kies welk gedeelte u wil aanvallen, dat op de vlakte of dat op de heuvel.' (The enemy is split into two commandos. Choose where you would like to attack, on the plain or on the hill?)

Potgieter was still not convinced that attack was the best option and retorted on the unevenness and unsuitability of the terrain. They had already encountered the extreme rockiness and the plethora of stones on their way down the pass.(7) He reminded Uys of the number of gullies and dongas in which even more Zulus could be hiding. Neither of the leaders were aware of the third regiment (the left horn) which lay hidden behind Italeni, causing them to severely underestimate the strength of their adversary. It was Uys's personality which carried the day. Impetuous, fearless and with a good measure of hubris, he forced Potgieter into battle.

He gave instructions to his second in command, Jakobus Potgieter, to tend the pack horses and not to get involved in any fighting(8), and allocated twenty men from each commando to assist in this vital task.

Piet Uys left with his men forth with, crossing the Nzololo where the pack horses were stationed. He travelled east for approximately 250 metres before turning north towards Italeni, crossing the reed creek. Hatting's recollections painted the scene: 'de kaffers zaten tegen de helling van 'n berg. En om bij hen te komen, moest men lelike en steile sloten door, waar maar weinige en dan nog slechte driften waren.' The commando rushed uphill and stopped only fifty metres from the nearest Zulu line(9), still sitting imperturbably on their shields. They came so close that one of the riders, Gert Viljoen, asked his field cornet, Grootvoet Potgieter: 'Ek sê, neef Koos, wil julle die goed dan met die hande vat?' (I say, do you want to greet them by hand then?)

The commando formed a line of about two hundred metres and dismounted. Suddenly a Zulu Induna sprang up and yelled at his men to attack as soon as the Trekkers fired. W.G. Nel remembers: 'Zodra de witten mensen schiten, moeten jullie stormlopen.' Louis Nel concurs and adds that Piet Uys immediately ordered his sharpshooter (sniper), Pieter Nel, to shoot the Induna: 'Pieter, skiet daardie kaffer.' The Induna became the first casualty of the day. His shot was immediately followed by a volley from the Trekkers, resulting in grave losses on the Zulu side. A second volley rang out which caused consternation in the opposing forces. The Uys group then heard the first volley from Potgieter's men, with Uys urging his men on by yelling 'steek hulle onder die loopers!' (Start using buckshot!). The white shields took flight, running back down the hill in the direction of uMgungundlovu. What seemed to Uys and his men as a rout, was in fact a brilliant tactical withdrawal by the Zulus, to draw the emigrants over the kopje. As they mounted their horses, they noted that the Potgieter men were hastily retreating before a large contingent of attacking Zulus (the right horn).(10)

The Uys commando followed the retreating Zulus, finding it difficult to avoid all the slain bodies strewn at the summit.(11) The cohesion of the attacking force was immediately lost, and they scattered into small parties, each one hunting his foe. In the words of W.G. Nel: 'van alle direkties achtervolgen wij nu de vijand.'(12) or Hatting: 'waarop de menschen zich dadelik verspreidden en hen achterna setten.'.(13) According to Boshof: "The Zulus took flight and the trekkers separated into small parties and were all in mortal danger."

The confrontation went exactly as predicted by Ndlela.

Potgieter's attack

Uys rushed off across the Nzololo stream, the dubious Potgieter started cautiously on the western side of the stream. His men carefully examined the gardens and gullies for hidden warriors. He continued vigilantly, but slowly towards the rift, mindful of the approaching Zulus. He reached the drift some three hundred meters downstream and halted. Uys and his commando were now out of view. According to M.J. Oosthuizen he stopped advancing, and "seer kout blijf staan aan dese kant van een spruit."(14) He then sent some sixteen to eighteen men forward, instructing them to advance towards the oncoming Zulus, but not to dismount at all.

Potgieter gave the sign by raising a piece of white cloth and the small group fired their first volley. This incensed the column of Zulu warriors, who now re- doubled their efforts, yelling, screaming and thumping their assegais on their shields. Their rage was obvious to the men, who quickly turned and fled. Only Joseph Kruger had dismounted, disbeying orders; the confused and panicked animal kicked him while he was trying to mount his horse. Kruger slipped and the advancing horde of enraged warriors killed him within seconds.

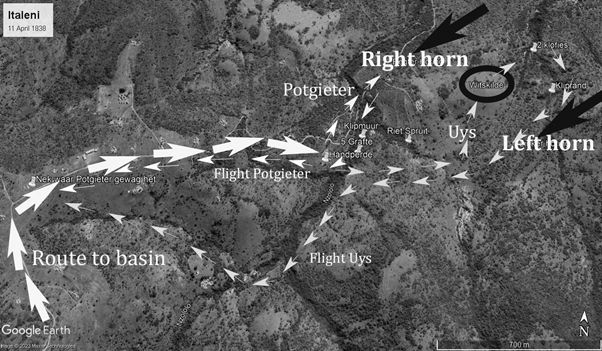

The battle took place on and around Italeni hill in an area of approximately 900sq m.

There were 600-700 Zulu fatalities, and ten Voortrekkers lost their lives. The white shield

warriors were at the black oval, while the horns were hidden from the trekkers

The Potgieter commando was now in full flight. Several men charged straight back from the drift into the bed of the stream while others galloped across the low-lying ridges, all barely keeping ahead of the marauding Zulus. With only moments to spare they escaped to their pack horses and managed to free only their own animals. The men turned towards the pass, rushing up along the footpath at the right of the small hill to their left, and staying to the right (north) of the donga. After the first incline they turned and shot at the pursuing warriors.

The fleeing men could see that the Uys commando were also hastily retreating in front of the pursuing left horn, coming down in small groups from the neck towards the reed creek. The Potgieter men frantically waved their hats to warn the fleeing men of the right horn which was now blocking them at the zololo stream.

Uys in trouble

The Uys commando was in disarray. They noticed a third force, the left horn, rushing past them on the eastern side towards the neck, which was now far behind them. During the ensuing melee Uys noticed two of his men, the brothers Malan, were in trouble, some two hundred metres ahead of him at a place where two woody gullies joined.(15) Most of the Voortrekkers now realised their folly and imminent danger, and started retreating towards the neck, racing the advancing left horn to the reed creek. Uys requested the help of fifteen volunteers, including his son, Dirkie, to assist the stricken brothers. They all rushed down the hill, in the opposite direction to the fleeing commando. Uys, together with Jan Meyer, managed to free the two brothers, with the rest of the volunteers a short distance behind.

Uys, still on the northern side of Italeni Hill (1), noticed the plight of the brothers Malan in two woody gullies (2). He enlisted 15 volunteers and rushed in an opposite direction of the fleeing Voortrekkers to save the brothers. Here, he was mortally wounded. The group moved along the eastern side of the gulley up to where a stony ridge abuts the rocky creek. The Voortrekkers had to fight their way up towards the neck. The Malans were killed along this uphill (3) and Pieter Nel died on the downhill towards the reed creek (4). Uys faints for the third time and succumbs to his wounds on the southern side of the reed creek (5). The distance from wounding to expiring is about 900m which fits well with the calculated "time-to-die. (Six minutes travelling and three to four minutes for reviving the stricken Uys. This all happened while the group was being ferociously attacked by the Zulu left horn).

Colour version of photograph in Journal

Uys stopped briefly to adjust the flint of his weapon when two Zulus leapt up from the tall grass, each hurling an assegai. Uys was struck in his lower back, while Meyer's horse was mortally wounded. Uys managed to withdraw the assegai and blood streamed from the wound.

The wound

Wide discrepancies and contradictions have arisen about the nature and position of Uys. injury. Witness accounts vary, some claiming the assegai pierced his thigh; others claiming his groin, hip or lower back were struck. The exact nature of his injury is important to determine the course of the rest of the battle.

Uys could have lived for hours had the wound been in his thigh, and he then might have died at the red gulley(16) at Itala, where his son Kruppel-Koos Uys averred to have found his father's remains. However, if an organ such as the spleen (or a major blood vessel) had been penetrated, the time-to-die would not have exceeded ten minutes, especially considering the continuous movement on horseback.

The salient points of the witness accounts are as follows:

(a) There was dramatic external bleeding. One of the volunteers. first thoughts was that Uys' horse was wounded, due to the amount of blood on the horse's flank. "Kyk, die Palomina is gewond met 'n assegai, kyk al die bloed op sy flank.".(17) (See, the horse was wounded. Look at all the blood on his hindquarters.)

(b) Jan Meyer, who had to be lifted onto Uys' horse, was wholly smeared with Uys' blood. According to J.H. Steenkamp: "hy, Jan Meyer's, klederen waren rood geverfde door het bloed van Uys."(18) (Jan Meyer's clothing was painted red by the blood of Uys).

An injury to the thigh or groin could not have resulted in the bleeding pattern as described by these two witnesses. An injury to the groin would have resulted in anterior (frontal) bleeding down the horse's abdomen.

(c) Substantial internal bleeding emanated from the lungs (or stomach). This was attested to by W.G. Nel, who remembered: "Toen hij bij ons terug-kwam, hep.t bloed hem bij neus en mond uit." When he returned to where we were, blood streamed from his nose and mouth.)"

When one reconstructs the incident in the mind's eye, understanding the nature of the injury becomes clearer: Uys sits on his horse, slightly bent forward and to his right side, fumbling with his flint lock. A Zulu warrior leaps from the grass, behind and to the left of him, and throws his assegai upwards. The assegai hits Uys' spleen, and the momentum forces the assegai through his diaphragm into his lungs. External bleeding happens immediately, but it takes a minute or so for the blood to accumulate internally before running from his nose and mouth. The internal bleeding was far more serious than the actual wound site.

One can speculate that it took roughly two minutes to remove the assegai and assist Meyer to piggyback on the horse, before they continued. This would have left only eight minutes for the group to move onward again, with Uys fainting and being revived twice, before he succumbed to his injuries. One can accept that they would not have been able to move along at more than a fast-walking pace, or at most a trot. Their average speed can be calculated to be no more than eight kilometres per hour or 2.5 meters per second, making it about 900 metres before Uys would expire. According to Boshof, two men steadied Uys on either side of his horse(19) and rode alongside him.

The stony ridge

According to W.H. Nel they first had to cross a stony creek, which placed them on the north-eastern side of the eastern gulley. From there they reached the stony ridge. "Aan de overzijde van genoemde spruit was 'n kliprif, dat opliep naar 'n kopje."(20) (On the other side of the creek a stony ridge led to a hillock.)

Nel is a keen observer, and his recollections detailed, but in this instance the author is convinced that he made a chronological mistake.(21) He reported that the stony ridge incident took place after the death of Pieter Nel, who, one can infer, died on the downhill slope on the southern side of the neck, going towards the reed creek. The narrative does not fit the terrain investigation. The only rocky ridge is on the northern side of Italeni, comprising the ridge, a hillock, and a small rocky creek. One can only follow Nel's narrative when the two events are switched, and then every detail becomes logically clear.

The stony ridge as described by W G Nel

Colour version of photograph in Journal

The "Fifteen" were split for a short time, with some going left and others to the right of the stony ridge, constantly fighting off the raiding Zulus. When the men regrouped, Uys fainted for a second time.

They managed to revive him, only to see that the brothers Malan were killed at that moment.(22) The enemy was now approaching so thick and fast that the volunteers had to open a gap to escape by all shooting in the same direction. The group then managed to cross the neck and race down towards the reed creek.

Pieter Nel's horse stumbled on the rocky terrain, and he was dislodged, toppling to the ground, injuring the left side of his face.(23) His brother, W.G. Nel, managed to catch the horse, but Pieter was felled by an assegai as he tried to remount. He was killed within seconds by the battle-raged Zulus. The hapless group continued, but Uys collapsed again as they reached the reed creek.

The death of Uys

When Uys was revived for the third time he ordered his men to leave him and flee. The Moolman brothers, together with Gert de Jager, helped Uys to cross the creek, but once he had reached the other side, he collapsed one final time and died.

W.G. Nel and Louis Nel claimed that Uys' son, Dirkie, who was also in their group, was killed on the far side of the creek, before he could cross it, and that father and son lay metres from each other, with the reed creek separating them. Schalk Burger averred that Uys died soon after he assisted Jan Meyer: "niet te ver echter, zei Uys: Los my maar, ek sterf hier."(24)

Boshof, in the "Annals of Natal", concurs with Schalk Burger that Uys died before he reached the Nzololo stream and the rockface. According to Boshof's narrative, Uys was still at the reed creek while his son Dirkie fled towards the Nzololo stream. Dirkie looked back at his father from about one hundred metres, then turned back in shame to fight and die alongside his stricken father.(25, 26). If one is to accept the versions of Boshof, Burger and Louis Nel, one can accept that the event happened between the Nzololo stream and the reed creek, albeit closer to the creek.(27) It is the only flat ground from which Dirkie would have been able to see his dying father, and rush back to him.

The rockface

The rockface where so much of the commotion took place is in the Nzololo stream and much further down-stream that what was previously postulated. There was a desperate struggle as the men hastily lead their horses on the narrow footpath while their fellow combatants held the enemy at bay. The Nzololo carved a deep ravine upstream, and the Voortrekkers were hemmed in, fighting constant hand-to hand battles with their foe. Three of the trekkers were killed during this confusion. The father of the Malan brothers, Dawid Malan, and Gerrit Cornelius (Theuns) and Louis Jacobus Nel died here.

The rockface is further downstream than was

previously described. After crossing the

obstacle via a small footpath, the Voortrekkers

were forced into a deep donga

from where escape was impossible.

Walter Door and Paul Smith found five graves nearby, on the eastern side of the Nzololo stream. It is the author's contention that Piet and Dirkie Uys were moved to be buried with their compatriots, but only archaeological research will be able to bear this out.

The escape routes.

At this stage Potgieter's men were already high up in the pass, close to the neck, where they awaited the rest of the commando. Piet Rudolph had already requested help from Potgieter, who apparently bluntly refused. Potgieter was only prepared to wait at the rim of the basin and kept the Zulus at a distance with sporadic fire. The chaos of the Uys commando down in the valley forced most of the men to spur their horses on to the eastern side of the Nzololo stream, upwards towards Kataza. The Uys group was totally blocked from the pass where the Potgieter men fled. The Uys commando had also lost their pack horses. They continued along the eastern side of the Nzololo stream, using the speed of their mounts to outrun the impis who followed. They crossed the stream above the second rockface, where H.C. de Wet initially posited the main battle took place. The men hurried along on the southern side of the hill towards the neck, where Potgieter and his men waited. Aftermath The battle lasted less than two hours. The men, dazed and shocked, stared at the valley below them, strewn with the bodies of fearless men - Zulus and Voortrekkers - who had died fighting.(28) The Zulus left the battlefield to return to uMgungundlovu, some 3 kilometres away. The Voortrekkers retreated to the Biggarsberg, across the Buffalo River, not fleeing, but also not lingering. Small groups of Zulus, possibly spies, followed them to see where they would dismount and unsaddle, but they never managed to launch another attack. The witnesses tell this story: P.J. Coetser: "Na deze ongelukkige onderneming de Boeren terug na hul laager." W.G. Nel: "Wij waren seer vermoeid en ons manschappen reden achter elkander in een lijn." J.H. Steenkamp: "Ongeveer 2 000 van den vijand achtervolgde ons aan een eind tot bovem op de rand, toen zy echter zagen dat wy elkander waren keerden zy terug." S.W. Burger: "Uiteindelik achtervolgen nog net 'n klein klompie Kaffers de mensen." and P.M. Fouche: "De kaffers zyn niet achter ons aangekomen, maar elf kaffers volgden ons om te sien waar wy de nag sou blyven." The next day, on the 12th April, Gert de Jager reached the laagers on his horse Tromp, known to be the fastest mount of the trek.(29) Exhausted and still in shock, he related the grim news to the people of the laagers.

Bibliography

Bird, J. (1888). The Annals of Natal - 1495-1845.

Pietermaritzburg: P Davis and sons.

Bornman, H. (1980). Een bladzijde uit de gescheidenis

van de voortrekkers. WG Nel. Die familie Nel van Nelspruit. Ongepubliseerde Manuskrip.

Bornman, H. (2004). Die familie Nel van Nelspruit.

Barberton: SA Country Life

Burger, S. W. (1922). Herinneringe. In G. Preller,

Voortrekkermense IV (pp. 92-97). Kaapstad: 1922.

Coetzer, P. J. (1922). Herinneringe. In G. Preller,

Voortrekkermense IV (pp. 40-43). Kaapstad:Nasionale Pers.

Cory, G. E. (1926). The Diary of the Rev. Francis

Owen MA. Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society.

De Wet, H. C. (1955-58). Werkstukke oor die soektog na Italeni.

Italeni. Ongepubliseerde manuskrip verkry van Nico Harris.

De Wet, H. C. (1959, Vol 4 No 2). Waar het Piet Uys

en sy Seun Dirkie geval? Historia, pp. 75-88.

De Wet, H. C. (1963, September 1). Die grafte van

Piet en Dirkie Uys ontdek. Historia, pp. 166-174.

Du T. Spies, F. (1959). GA Ode Sy bydrae tot ons

kennis van die Groot Trek. Historia Vol 4 No 2, 119-127.

Du Toit, P. (1938, Desember). Die Slag van Italeni.

Huisgenoot, p. 119 & 185.

Fouche, P. M. (1958-1960). Brief gedateer 1896 Zyfergat.

In H. C. De Wet, Werkstuk versameling(pp. 73-75). Greytown:

Gibson, J. Y. (1911). The story of the Zulus. London: Longmans.

Grobler, J. (2008). Afrikaner en Zoeloeperspektiewe op die

slag van Bloedrivier, 16 Desember 1838. Tydskrif vir

Geesteswetenskappe, 50(3). Pretoria. Sept 2010.

Haarhoff, G.I. 2018. Forgotten tracks and trails of

the escarpment and the Lowveld. Nelspruit: Forgotten Tracks and Trails (Pty) Ltd

Hamman, J. (2022, Sept 20). Blood on Italeni Hill.

Retrieved from History’s Walk: https://www.historyswalk.co.za/?p=804

Harris, N. (2022, Julie 13-14). Besoeke aan die

Italeni / Nzololo slagveld. (G. Haarhoff, Interviewer)

Harris, W. C. (1852). The wild sports of Southern

Africa. London: Henry G Bohn.

Hatting, J. H. (1918). Herinneringe. In G. Preller,

Voortrekkermense I (pp. 165-169). Kaapstad: Burgerleeskring.

Hofmeyr, I. (1987). Popularising History: The case

of Gustav Preller. University of the Witwatersrand, 1-34.

Kmdt. Petrus Lafras Uys. (2020, 03 01). Retrieved

from Geni.com: https://www.geni.com/people/

Kmdt-Petrus-LafrasPiet-Uys/6000000006780540316

Markram, W. J. (2001). Die lewe en werk van

Petrus Lafras Uys 1979-1838. Stellenbosch: Promotor C Venter.

Nel, F. G. (2020, 02 16).

Retrieved from Familie Legkaart:

http://familielegkaart.blogspot.com/p/nel.html

Nel, W. G. (1922). Herinneringe. In G. Preller,

Voortrekkermense IV (pp. 1-11). Kaapstad: 1925.

Oosthuizen, M. J. (1922). Herhinneringe. In G.

Preller, Voortrekkermense III (pp. 129-133).

Kaapstad: Nasionale Pers.

Owen, F. (1916). The diary of the Rev Francis Owen.

Cape Town: van Riebeeck Society.

Prinsloo, J. W. (1968, Maart Vol 13 No 1). Die geskiedenis

van die voortrekker Uys familie. Historia, pp. 33-35.

Smith, P. (2022, Julie 13-14). Besoeke aan die Italeni / Nzololo slagveld.

(G. Haarhoff, Interviewer)

Spies, F. d. (Vol 33 No 2 1988). Onsekerheid inverband met

die gelofte van 1838. Historia, 51-62.

Spies, F. d. (Vol 4 No 2 1959). GA Ode: Sy bydrae tot ons kennis

van die Groot Trek.Historia, 119-127.

Steenkamp, J. (1958). Herinneringe uit die De Wet versameling.

Greytown: Unpublised manuscripts.

Theal, G. M. (1915). The History of South Africa

Vol II. London: George Allen & Unwin LTD.

Uys, I. (1974). Die Uys-geskiedenis 1704-1974.

Heidelberg: Published by author.

Uys, I. (June 1979). The Battle of Italeni. Military

History Journal, Vol 4 No 5 p1-8.

Van der Walt, J. (2011). Zululand True Stories

1780-1978. Pretoria: Private Press.

Von der Heyde, N. (2013). Field guide to the

Battlefields of South Africa. Cape Town: Random House Struik

End Notes

About the author Dr Gerrit Haarhoff is a medical practitioner in Nelspruit and a keen amateur Historian. He has published a well-received book on the old wagon trails of eastern Mpumalanga titled Forgotten Tracks and Trails, for which he was bestowed with the Mpumalanga Heritage Award.

Letter to the Editor

Dr Gerrit Haarhoff – Battle of Italeni

On 11 April, 2023, Dr Haarhoff, Paul Smith and I gave talks at the Voortrekker Museum about the battle. Paul and I differed from Dr Haarhoff’s theories on the exact site of the engagement. While he believes that the battle took place north of the present farmhouse ruins (downstream), we know that it was to the south as:

All the graves are on the south side.

There are apparently two rock faces. A participant in the flight, Willem Nel, states that they led their horses over it, not around via a footpath which is possibly in the north.

Paul Smith found a contemporary map at the Killie Campbell Museum in Durban which shows the battle to have taken place upstream (in the south).

Ian Uys

17 Sept 2023

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org