The South African

The South African

SAS Sonneblom

SAS Fleur

SAS Amatola

SAS Frans Erasmus

Photographs in this article are by courtesy of the South African Naval Museum.

Introduction

The South African (SA) Navy of the truly democratic South Africa, dates back to 1994, and since then there have been many important developments and milestones, but the Navy can trace its history all the way back to 1922. What has been achieved since 1994, has been built on the work done in the course of many decades. In this article, an overview is provided of certain important events in the history of the SA Navy and its predecessors since 1922.(1) After all, the centenary of the Navy was an opportunity for all South Africans to reflect on its Navy’s history, to take stock of the Navy’s present state of affairs, and to look ahead and plan for the future. More constructive debate is needed in South Africa with regard to military matters, including the relevance and role of the SA Navy. And South Africa needs to become a truly maritime nation.

Throughout the ages, the politics and strategy of sea power was (and still is) of crucial importance for littoral countries; and sea power had (and still has) a profound influence on the history of the world. To ensure the free flow of trade around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, a naval presence was (and still is) very necessary. The development of South Africa's naval forces has to be seen against this background.

The SA Navy is neither one of the oldest nor one of the major navies in the world, but it nevertheless has a fascinating and proud history, albeit also a chequered history. South Africa is, everything taken into consideration, supposed to be a maritime nation. With oceans forming three of the Republic of South Africa (RSA)'s borders, the country is thus – geographically speaking – a large peninsula. It has a coastline of approximately 2 800 km and an exclusive economic zone that stretches 200 nautical miles (1 nautical mile = 1,852 km) from the coast into the oceans. When it is furthermore considered that at least 90 % of South Africa's trade flows through the country's harbours, it should be clear why the country should be a maritime nation, but in practice this is not necessarily the case. Too many South Africans suffer from what could be regarded as “sea blindness”.

Small wonder thus that South Africa’s naval forces have for most of its history been the Cinderella of the country’s armed forces. Until recently, not that much has been written about the SA Navy and its predecessors. General histories with regard to the Navy are: South Africa’s Navy: The First Fifty Years (compiled by JC Goosen and published in 1973 to commemorate the Navy’s fiftieth anniversary in 1972),South Africa’s Navy: A Navy of the People and for the People (by CH Bennett and AG Söderlund; published in 2008), and to commemorate 25 years of true democracy in South Africa in 2019, the Navy published The South African Navy: 25 Years of Democracy (compiled by Leon Steyn).

André Wessels has thus far published two books that deal with the history of the SA Navy, namely (in Afrikaans) Suid- Afrika se Vlootmagte 1922-2022 (published in 2017, to commemorate 90 years of naval history) and an expanded and differently presented book in English, A Century of South African Naval History: The South African Navy and its Predecessors 1922-2022 (published in 2022, to commemorate the Navy’s centenary). Other publications of note include Allan du Toit’s South Africa’s Fighting Ships Past and Present (1992), A Navy for Three Oceans: Celebrating 75 Years of the South African Navy (a richly illustrated commemorative book, published by the Navy to celebrate its 75th anniversary in 1997), Chris Bennett’s Three Frigates (published in 2006, which deals with the Navy’s three Type 12/”President” Class frigates), Chris Bennett’s South African Naval Events: Day-by-Day 1488 to 2009 (2011) and Robert Simpson-Anderson’s President Mandela’s Admiral (written by the retired Vice-Admiral, who from 1992 to 2000 was Chief of the SA Navy; published in 2021). See also the 34 editions of the Naval Digest which since 1999 have thus far (i.e. until 2022) been published by the South African Naval Heritage Trust.(2)

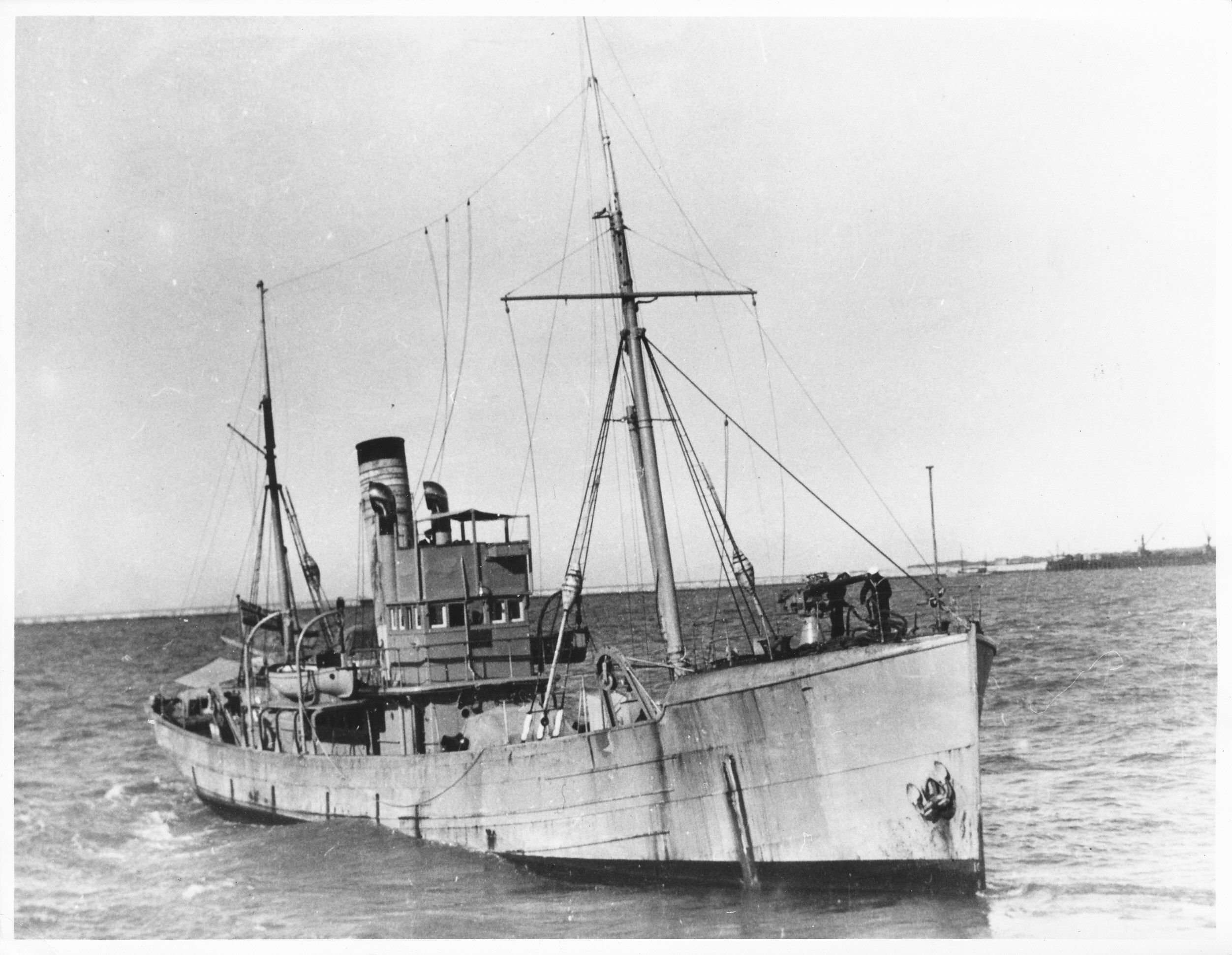

Establishment and developments, 1922-1945

In the course of the first century of its existence (1922-2022), South Africa’s naval forces have, on several occasions, undergone a process of transformation. Although the Union of South Africa was established on 31 May 1910, the Union Defence Forces(3) (UDF) were only established on 1 July 1912, but without a naval force. For more than a decade South Africa relied on Britain’s Royal Navy (RN) for coastal defence. But then the Prime Minister, General Jan Smuts, stepped in, and the South African Naval Service (SANS) was established on 1 April 1922 as a small coastal force, with only one survey ship (HMSAS Protea) and two minesweeping trawlers (HMSAS Sonneblom and HMSAS Immortelle). (See front cover painting). The world-wide Great Depression of 1929-1935 also affected South Africa and the UDF adversely, and led to the withdrawal from service of all three abovementioned ships.(4) As a consequence, from 1934 until 1939, the SANS existed only as a nominal naval force, with only a few personnel and no ships. In the meantime, war clouds gathered in Europe, and in September 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, the Second World War broke out.

HMSAS Protea the first of that name

The SANS became the Seaward Defence Force (SDF) in 1939, which in turn, was transformed in 1942 to become the South African Naval Forces (SANF). Under the leadership of South Africa’s wartime Prime Minister, General Jan Smuts, the UDF was expanded, including its naval forces. By the end of the war, more than 10 000 persons had served in the country’s naval forces, inter alia on board 88 naval vessels – mostly fishing trawlers and whalers that had been converted into minesweepers or antisubmarine vessels. These small ships were primarily used to patrol the seas off South Africa, but a number of them were sent to the Mediterranean Sea, where four were sunk due to enemy action. In total, 324 South African naval personnel lost their lives in the course of the war while in SDF/ SANF service. It was only in 1944-1945, that the SANF received its first “major” warships, namely three British-built “Loch” Class frigates: HMSAS Good Hope, HMSAS Natal and HMSAS Transvaal.(5) After the war in Europe ended, HMSAS Natal, as well as the boom defence ship, HMSAS Barbrake (later renamed SAS Fleur) were sent to the Far East to briefly serve in the war against Japan.(6)

In the course of the war, South Africa’s naval forces made a small but nonetheless noteworthy contribution towards the Allied war effort, while approximately 3 000 South Africans serving in the Royal Navy, saw action in all the war zones. A total of 191 South Africans died in RN service.(7) South Africa was spared physical attack, but 158 Allied merchant ships were sunk within 1 000 nautical miles off the South African and South West African (Namibian) coast, while only three German submarines were sunk in the same area.(8) More than ever before, the importance of safeguarding the Cape sea route was emphasized.

Consolidation and expansions, 1945-1975

After the cessation of hostilities, the SANF (renamed the SA Navy in 1951) was first down-sized, but expanded from 1947 onwards. In 1947, the SANF acquired two “Algerine” Class ocean (or fleet) minesweepers from Britain (soon named HMSAS Bloemfontein and HMSAS Pietermaritzburg)(9), as well as a Royal Navy “Flower” Class corvette, that was in due course converted into a hydrographic survey ship and commissioned as HMSAS Protea in February 1950.(10) Further expansions followed, with no fewer than eighteen new or second-hand ships acquired from Britain in the course of the 1950s: two “Wager” Class destroyers (commissioned as SAS Jan van Riebeeck and SAS Simon van der Stel in 1950 and 1953 respectively), one Type 15 frigate (SAS Vrystaat) which was commissioned in 1956, five “Ford” Class seaward defence (i.e. patrol) boats (SAS Gelderland, SAS Nautilus, SAS Rijger, SAS Haerlem and SAS Oosterland), which were commissioned in 1954 (one), 1955 (one), 1958 (one) and 1959 (two), and ten “Ton” Class coastal minesweepers (SAS Kaapstad, SAS Pretoria, SAS Durban, SAS Windhoek, SAS East London, SAS Port Elizabeth, SAS Johannesburg, SAS Kimberley, SAS Mosselbaai and SAS Walvisbaai), which were commissioned in 1955 (two), 1958 (four) and 1959 (four). This was mainly the result of the Simon’s Town Agreement of 1955, which also led to Britain handing over their Simon’s Town Naval Base to the SA Navy on 1 April 1957. (The handing over ceremony took place on 2 April 1957.) The SA Navy thus became a small, blue-water navy, capable of guarding the Cape sea route in the interests of South Africa and the West.(11)

One of two “Wager” Class destroyers (acquired in 1950 and commissioned as SAS Jan van Riebeeck)

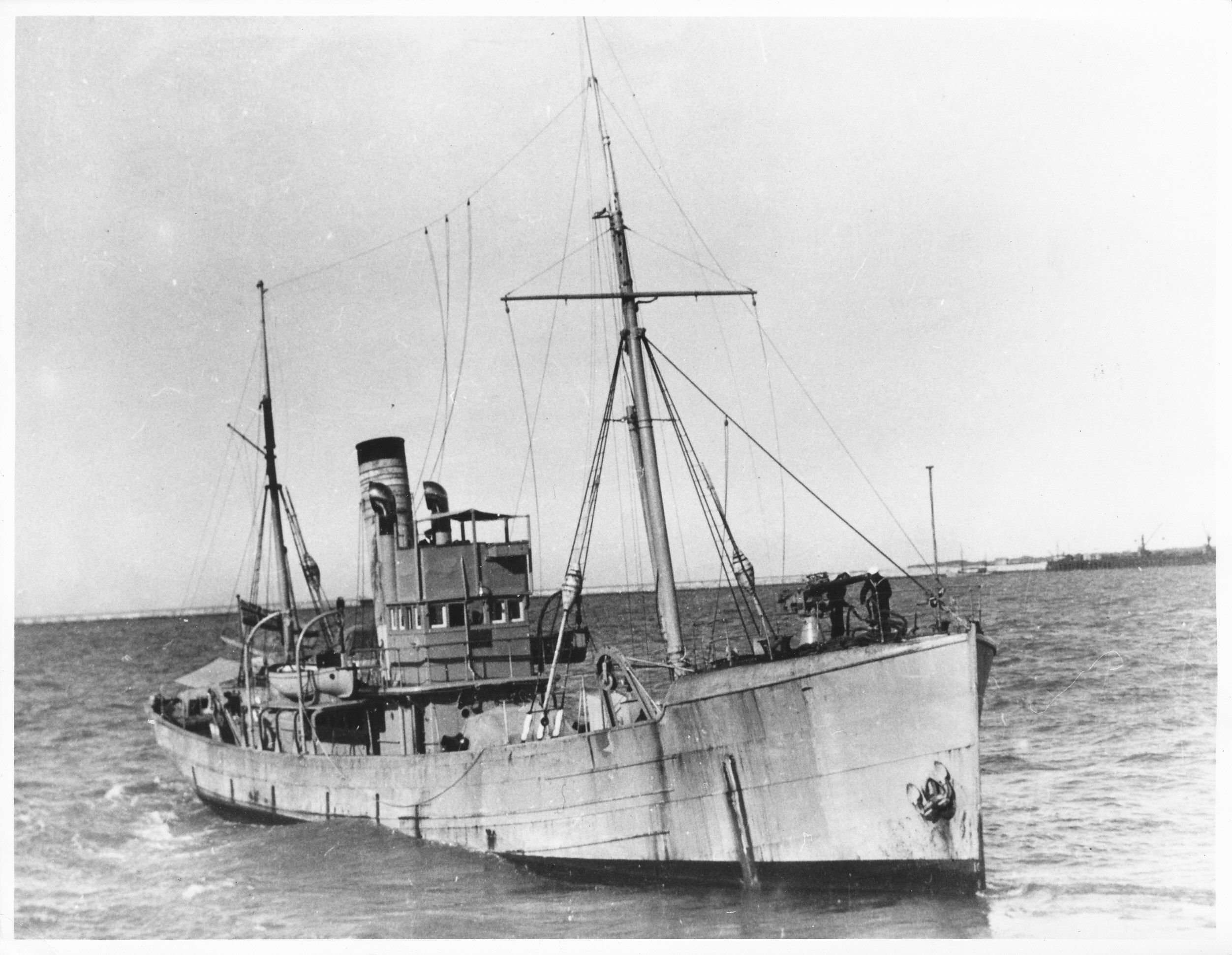

The Navy continued to expand in the course of the 1960s and 1970s, acquiring, inter alia, three new Type 12 frigates from Britain (SAS President Kruger, SAS President Steyn and SAS President Pretorius; commissioned 1962-1964)(12) and a replenishment ship (SAS Tafelberg; commissioned in 1967).(13) In 1969, the locally built (in Durban) torpedo recovery and diver support ship, SAS Fleur, was commissioned.(14)

SAS President Steyn, a Type 12 frigate from Britain, commissioned in the early nineteen sixties.

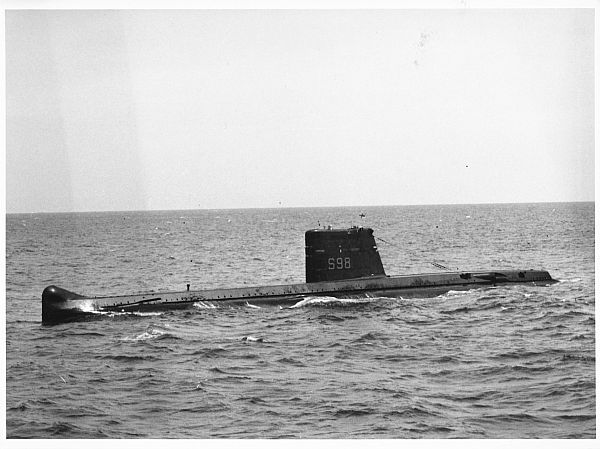

A Submarine Service was also established. The Navy wished to acquire British “Oberon” Class submarines, but in the light of a British arms boycott, decided to buy three French-built “Daphné” Class submarines (commissioned as SAS Maria van Riebeeck, SAS Emily Hobhouse and SAS Johanna van der Merwe in 1970-1971) which in practice proved to be a better choice. As part of a continuing transformation process, these three submarines were respectively renamed SAS Spear, SAS Umkhonto and SAS Assegaai on 19 May 1999.(15)

Submarine SAS Emily Hobhouse, later renamed SAS Umkhonto.

The last British-built naval vessel to be acquired, was the hydrographic survey ship, SAS Protea, in 1972 (which, fifty years later, still serves in the Fleet).(16)

[See the article about the SAS Protea in this issue - Editor.]

Antarctic research ship RSA, which was known as A331 while in the service of the South African Navy.

The war years, 1975-1989

The Navy entered the missile age, thanks to the acquisition of nine missile- carrying strike craft in the years 1977 to 1986: SAS Jan Smuts, SAS P.W. Botha (renamed SAS Shaka on 1 April 1997), SAS Frederic Creswell (SAS Adam Kok), SAS Jim Fouché, (SAS Sekhukhune), SAS Frans Erasmus, (SAS Isaac Dyobha), SAS Oswald Pirow, (SAS René Sethren), SAS Hendrik Mentz, (SAS Galeshewe), SAS Kobie Coetsee, (SAS Job Masego) and SAS Magnus Malan, (SAS Makhanda). The first three were built in Israel (Haifa); the others in South Africa (Durban). The Navy also acquired four minehunters in 1981, in due course commissioned as SAS Umkomaas, SAS Umgeni, SAS Umzimkulu and SAS Umhloti. They were designed in what was then West Germany, and the first two were built there, while the last two were built in Durban – all under the guise of research ships.(17) From 23 April 1978 until 17 March 1980, the former Antarctic supply and research ship of the South African Department of Transport, the RSA, served in the SA Navy, and used for electronic surveillance. She was simply known by her pennant number, namely A331.(18)

On 18 February 1982, the SA Navy suffered its biggest tragedy thus far, when the frigate, SAS President Kruger sank after a collision with the replenishment ship, SAS Tafelberg, some 78 nautical miles south-west of Cape Point. Sixteen lives were lost; 177

SAS President Kruger

SAS Tafelberg alongside one of the Type 12 frigates

For several decades, the SA Navy was the guardian of the Cape sea route. But the National Party’s policy of separate development (apartheid) led to ever-growing international isolation. Naval contact with other countries was limited. In 1977, in the wake of the mandatory United Nations arms embargo, the delivery of two “D’Estienne D’Orves” Class corvettes and two “Agosta 70” Class submarines was cancelled by the French government. By 1985, the SA Navy was reduced to a small-ship navy that concentrated on the defence of South Africa’s harbours and coasts, albeit the Navy did play an important (some will say controversial) role in the War for Southern Africa (which included the so-called Border War), especially in the years 1975 to 1988. During “Operation Savannah” (the South African invasion of Angola, 1975-1976), the frigates, SAS President Kruger and SAS President Steyn, replenishment ship, SAS Tafelberg, as well as the submarines, SAS Maria van Riebeeck and SAS Johanna van der Merwe, supported the South African ground and air forces.(20) Later, the SA Navy’s submarines and strike craft, supported by SAS Tafelberg, SAS Protea and SAS President Pretorius (until this frigate was withdrawn from service in 1985), deployed Special Forces (Recces) “behind enemy lines” in Angola and in Mozambique.(21) In the meantime, in 1987, the SA Navy commissioned a second combat support ship, namely SAS Drakensberg – the largest of any kind of ship thus far designed and built in South Africa.(22)

A new dawn

After the combat support ship, SAS Tafelberg was withdrawn from service in 1993, she was that same year replaced by the former Ukrainian-built Arctic support ship, Juvent, which was transformed by the SA Navy into a combat support ship, and commissioned as SAS Outeniqua.(23) The run-up to and dawn of a new and truly democratic South Africa in 1994, indeed created new opportunities for the SA Navy. For the first time since the late 1970s, SA Navy warships were welcome to visit other countries, and soon many foreign warships (and from time to time also submarines) visited South African ports; sometimes to replenish fuel and stores, but most of the time during tailor-made flag-showing cruises. A highlight in this regard was in March-April 1997, when the SA Navy commemorated its 75th anniversary with, inter alia, an international naval review in Table Bay on 5 April, in which no fewer than 22 warships from 13 countries participated, together with fourteen SA Navy warships and a submarine.(24)

In the year 2000, six second-hand Type 351 minesweepers were bought from Germany, and two of them were in due course commissioned (SAS Kapa and SAS Thekwini) and briefly served in the Navy.(25) Thanks to the commissioning of four new “Valour” Class frigates (SAS Amatola, SAS Isandlwana, SAS Spioenkop and SAS Mendi)(26) and three new Type 209/1400 MOD(SA) submarines (SAS ‘Manthatisi, SAS Charlotte Maxeke and SAS Queen Modjadji I) from 2006 to 2008, (27) the Navy regained its blue-water status, and enhanced its power.

SAS Isandlwana alongside SAS Amatola.

SAS MEKO, an Amatola class Frigate.

In an effort to support the new frigates and submarines, the SA Navy acquired two new harbour tugs, namely the Imvubu (2015) and Inyathi (2016), to replace the De Neys (1969-2015) and De Mist (1978-2016), and to supplement the Umalusi (acquired in 1997). The new dockyard launches (DLs), Indlovu (2006) and Tshukudu (2006), replaced DL2 (1969-c.2006) and DL4 (1973-2006). Since 1957, several other DLs had also served in the SA Navy. Mooring Lighter No. 14 served the RN in Simon’s Town from 1901 to 1957, and the SA Navy since then.(28)

In the course of its history, many other vessels and craft served in the SA Navy, for example, the boom defence vessels, HMSAS Barbrake became SAS Fleur (1943-1965) and HMSAS Barcross/SAS Somerset (1943-1986); the sea-air rescue launches P1551 (1969-1997), P1552 (1969-1988), P1554 (1973-1986) and P1555 (1973-c.1992); the T-craft, SAS Tobie (1992-present), SAS Tern (1996-present) and SAS Tekwane (1996-present); and the navigation training vessel, Navigator (1964-1993).(29)

Submarine SAS Charlotte Maxeke.

Concluding Perspectives

In the course of a century since 1922, South Africa’s naval forces have provided support to other government departments, have taken part in numerous search-andrescue operations, as well as humanitarian and other support operations. Navy ships and submarines have also successfully taken part in many exercises, from the “DURBEXs”, “CAPEXs” and “SANEXs” of the 1940s to the 1960s (mostly with ships and submarines of the RN), to the “new” SA Navy’s participation in, for example, “ATLASUR” (with the navies of Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay), “IBSAMAR” (with the navies of India and Brazil), and “Good Hope” (with the German Navy). Other achievements of the Navy include the fact that at certain crucial times in its history, its leaders were able to convince the politicians that money had to be allocated to expand the Navy, including new submarines and frigates. The last- mentioned acquisitions were not only necessary lifebuoys for the then ailing Navy, but indeed gave it more tools and confidence to fulfil its mandate. They have also, since 2011, played an important role in the Navy’s counter-piracy “Operation Copper” in the Mozambique Channel. In the light of an insurgency problem in Mozambique’s Cabo Del-gado Province since 2017 and military intervention by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), SA Navy warships have since 2021 from time to time been deployed off the coast of that province.(30) Since 1922, South Africa's naval forces have also done excellent survey work along the country's coasts, making it safe for ships to sail along the coasts, and to enter and exit the ports. It is thus commendable that a new hydrographic survey ship is at the moment (2022) being built in Durban for the SA Navy, scheduled to replace SAS Protea in 2023. Meanwhile, three multi- mission inshore patrol vessels are being built in Cape Town to replace the remaining patrol boats (former strike craft) and minehunters in 2022-2024.(31)

Everything considered, the biggest achievement of South Africa's naval forces since 1922, and in particular since 1988, has been its diplomatic outreach actions. Throughout the ages it has been the practice of seafaring countries to send warships to one another from time to time; sometimes to take part in joint exercises, but usually to establish better relations or to strengthen ties that already exist. In this regard the SA Navy is no exception. Since the end of the Second World War, 60 of the country's 68 major warships have conducted approximately 100 flag-showing cruises, visiting more than 100 ports in approximately 50 countries. Of particular importance in this regard has been the role played by the SA Navy in the African context, as well as in the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean rim areas.(32)

In accordance with the SA Navy's core business, namely "To fight at sea", its mission, namely "To win at sea", and its vision, namely "To be unchallenged at sea",(33) it is of the utmost importance that the RSA should have a well-equipped, well-balanced, well-trained and disciplined navy. There are those who (erroneously) argue that South Africa is under no military threat. But what about terror groups and other threatening organisations? What about piracy? What about the unstable international situation, especially thanks to super/great power rivalry in the Far East, and now (2022) also again in Europe?

South Africa as a political entity is the product of the rivalry between seafaring nations (namely, the Netherlands, France and Britain) for control over the world's most important trade routes, including the Cape sea route. However, most South Africans have a land-bound culture. Small wonder that there are people who also do not appreciate the value of the country's navy. Hopefully this will change sooner rather than later.

In the years 1922 to 2022, South Africa’s naval forces developed a proud tradition with regard to support and assistance to South Africa and all its inhabitants. The SA Navy must build upon this tradition, and hopefully, all South Africans will appreciate and support their navy. After all, the SA Navy has indeed been transformed into a navy of and for all the people of South Africa.

NOTES

1 This article is to a large extent based on the research that was done for the book of André Wessels: A Century of South African Naval History: The South African Navy and its Predecessors, 1922-2022, S.I., Naledi, 2022. See this book for additional information on all the matters referred to in this article, as well as the book’s source list for publications that can be consulted for further reading.

2 For books that deal with the role played by South African naval forces in the Second World War, see Note 5 below.

3 Plural. As from 1922, the UDF was called the Union Defence Force (singular).

4 For an excellent review and analysis of the history of the SANS, see Allan du Toit: ‘A Navy for the Nation: The Fledgling South African Naval Service 1922-1940’ (Naval Digest, No 33, 2022).

5 For South Africa’s role in the Second World War’s naval war see, for example, LCF Turner et al.: War in the Southern Oceans 1939-1945, Cape Town, Oxford University Press, 1961; CJ Harris: War at Sea: South African Maritime Operations during World War II, Rivonia, Ashanti,1991; HR Gordon-Cumming: Official History of the South African Naval Forces during the Second World War (1939-1945), Simon’s Town, Naval Heritage Trust of South Africa, 2008; and Evert Kleynhans: The Naval War in South African Waters 1939-1945, Stellenbosch, Sun Press, 2022.

6 For South Africa’s role in the war against Japan, see André Wessels, ‘South Africa and the War against Japan 1941-1945’, Military History Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3, June 1996, pp.81-90, 120.

7 Naval Digest, No. 5, 2001, pp.1-12, and Naval Digest, No. 13, 2008, pp.23-59.

8 Wessels: A century of South African Naval History op. cit., pp.77-79.

9 Naval Digest, No. 6, June 2002, pp.3-12.

10 SA Naval Museum (Simon’s Town), SAS Protea (File 1).

11 Allan du Toit: South Africa’s Fighting Ships Past and Present, Rivonia, Ashanti, 1992, pp.193-196, 199, 201-219.

12 Chris Bennett: Three Frigates, Durban, Just Done, 2006.

13 Du Toit, Fighting Ships op. cit., pp.240, 244.

14 ibid., pp.247, 249.

15 Through the Periscope. South African Submarines: The First Thirty Years. Reflections Past and Present, Simon’s Town, 1999.

16 Du Toit, Fighting Ships op. cit., pp.263, 266.

17 ibid., pp.310-311.

18 ibid., pp.290-293.

19 Bennett op cit., pp.187-206.

20 FJ du T Spies: Operasie Savannah: Angola 1975-1976, Pretoria, S.A. Weermag Direktoraat Openbare Betrekkinge, 1989.

21 Douw Steyn and Arnè Söderlund: Iron Fist from the Sea: South Africa’s Seaborne Raiders 1978-1988, Solihul, Helion, 2014.

22 André Wessels, ‘SAS Drakensberg’s First 25 Years: The Life and Times of the SA Navy’s Foremost Grey Diplomat, 1987-2012’, Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol. 42, No. 2, 2013, pp.116-141.

23 Navy News, Vol. 12, July 1993, pp.1013; Navy News, Vol. 13, January-February 1994, p.13.

24 André Wessels, ‘Three Fleet Reviews – and the South African Navy’, Journal for Contemporary History, Vol. 39, No. 1, June 2014, pp.153-176.

25 Navy News, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2001, pp.14-15; Navy News, Vol. 20, No. 5, 2001, pp.20-21; Bennett and Söderlund op. cit., p.101.

26 The Mercury, 10 January 2007, p.6; South African Soldier, Vol. 9. Vol. 1, January 2002, pp.21-23.

27 CH Bennett and AG Söderlund: South Africa’s Navy: A Navy of the People and for the People, Simon’s Town, S.A. Navy, 2008, pp.108-109, 111, 113-114.

28 B Rice, ‘Simon’s Town Tugs’, Simon’s Town Historical Society Bulletin, July 20 2016, pp.29-39; Navy News, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2002, p.24.

29 André Wessels: Suid-Afrika se Vlootmagte 1922-2012, Bloemfontein, Sun Press, 2017, pp.245-246, 250, 252.

30 Spindrift, September 2021, p.6 and October 2021, p.6.

31 Navy News, Vol. 37, No. 2, 2018, p.9; Navy News, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2019, pp.8-9; Navy News, Vol. 40, No. 2, 2021, p.15; Navy News, Vol. 40, No. 6, 2021, p.10; Spindrift, December 2020 - January 2021, p.5.

32 See, for example, André Wessels, ‘South Africa’s Grey Diplomats; Visits by South African Warships to Foreign Countries, 1946-1996’, Scientiae [sic] Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol. 27, 1997, pp.67-105.

About the author

André Wessels was born in Durban, and grew up in that port city. He completed all his undergraduate and postgraduate studies at the University of the Free State (UFS), including a D.Phil. in 1986. He joined the Department of History at the UFS as a Lecturer in 1988, and retired at that university as a Senior Professor in 2021. He is continuing his association with UFS as a Research Fellow. His main field of research is twentieth-century South African military history, focusing in particular on the Anglo-Boer War, as well as on the South African Navy. He is the author, co-author or editor of eleven books, some 200 articles, and many other publications, including book reviews.

[These photographs were on the third last page of the physical Journal.] p>

HMSAS Brakpan

Old SA Navy Badge

River Class MCM

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org