The South African

The South African

Take Station Astern. With that historic signal on 28 November 1921, the survey ship HMS Crozier and the two small minesweeping trawlers, His Majesty's Ships Eden and Foyle, cleared the break-water at Plymouth in England and moved off to become the first units in the Empire's youngest Navy. After forging their way through the storms and sunshine of the Atlantic, the three ships finally entered Simon's Bay on the evening of Wednesday 11 January 1922. After lying quietly at anchor for the night, the ships finally went alongside the following morning to a small, low-key welcome in the lead up to the establishment of the fledgling South African Naval Service three months later on 1 April 1922.(1)

Although it had been more than a decade since the unification of the two British South African colonies and the two former Boer republics before a small South African naval service finally became a reality, there had been significant naval developments during that intervening period.

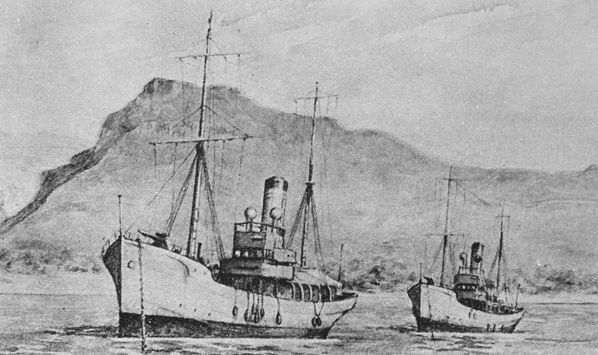

HM Ship’s Eden and Foyle at anchor in Simon’s Bay.

(The Africana Museum)

With the new Union’s defence remaining an integral component of the British imperial system,(2) South Africa had continued to rely on British sea power for its ultimate security. By 1910, the Cape of Good Hope had become one of Admiral Fisher’s ‘Five strategic keys’(3) that locked up the globe.(4) The Cape was positioned at the natural choke point of global shipping lanes between two of the world’s major oceans, the Atlantic and Indian oceans.(5) And with unmatched surveillance of both these oceans, the extensive new naval base and dockyard at Simon’s Town, which had been formally opened by The Duke of Connaught in November 1910, controlled and safeguarded the southern extremity of this vital sea route at its point of concentration.(6)

HM Dockyard, Simon’s Town circa 1910

showing its sheltered basin and graving

dock capable of accommodating the

latest battleships and battle cruisers,

together with its extensive workshop

facilities. It became base for the vessels

of the Cape of Good Hope Station when it

was completed in 1910.

(Du Toit Collection)

With the passing of the South African Defence Act in April 1912, the new Union Government had continued to meet the former Cape Colony and Natal’s combined annual unconditional contribution of £85,000 towards the naval defence of the Empire.(7) This ongoing contribution, in the absence of a South African naval force, had been seen as a necessary insurance premium by the government.(8)

Under Section 22 of the Defence Act, which, not unlike the post-1944 period, had brought the disparate colonial and Boer armed forces and militias together in one military organisation, the two part-time colonial naval volunteer units in the Cape and Natal (9) were finally amalgamated by statute to form the South African Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, the RNVR(SA).(10)

The RNVR(SA), which had officially come into being on 1 July 1913, formed the naval component of the Union’s Active Citizen Force in which volunteers could serve in lieu of fulfilling four years compulsory part-time military training in the army.(11) For practical reasons, and to ensure training and inter-operability with the Royal Navy, the South African government gave the Commander-in-Chief Cape of Good Hope Station responsibility for the Division's peacetime training, organisation, administration and discipline.(12)

The RNVR(SA), which was primarily intended for local naval defence, was funded by the South African Parliament separately from the Union’s annual contribution to the Royal Navy and was constitutionally part of the new Union Defence Force. With its unbroken linage, close linkage to the formation and functioning of the South African Naval Service and its successor, the Seaward Defence Force, and its eventual amalgamation with the latter to form the South African Naval Forces in 1942, a convincing argument could be mounted that 1 July 1913 is in fact the true birth date of the South African Navy.

As part of the Union’s reliance on the Royal Navy for its ultimate security and the protection of its seaborne trade, it was envisaged that in war or emergency, the RNVR(SA) would be placed at the disposal of the British Admiralty. This was to be the case not long afterwards with Britain’s declaration of war in August 1914.(13) Members of the Division subsequently served at sea and ashore with the Royal Navy both locally and in all theatres as part of the Royal Navy until the end of World War I.(14)

The First Overseas Contingent of the

RNVR(SA) before departing Cape Town

for Britain on 9 October 1915.

South African sailors subsequently served in

almost every theatre of war.

(SA Naval Museum)

In July 1920, Smuts, who had become leader of the governing South Africa Party and prime minister following the sudden death of General Louis Botha, explained at length the Union Government’s overall naval policy. This policy was underpinned by continued reliance on the Royal Navy which remained the world’s most powerful naval force with its web of naval bases, shore installations and its advanced communications and intelligence networks.(15) Smuts considered this continuing reliance, which provided the Union with significant strategic and economic benefits, to be a ‘business matter’ and one of ‘cold South African self-interest’.(16)

The overall policy outlined by Smuts reflected the detailed work of the Union Secretary for Defence Sir Roland Bourne, who had developed a comprehensive postwar naval policy for the Union in consultation with the British C-in-C Africa Station.(17) Bourne had also formulated practical options for a South African contribution to Imperial naval defence, together with options for the expansion of the RNVR(SA) and the establishment of a small permanent South African naval service.

The very capable Bourne, who had been closely involved in the establishment of the RNVR(SA) and in initial pre-war discussions with the Admiralty on South Africa’s contribution to imperial naval defence, discussed and further developed these proposals with the Admiralty in the lead up to the 1921 Imperial Conference in London.(18) His biggest challenge was finding what he called ‘useful objects’ of local naval expenditure that would be beneficial to both South Africa and the Empire as a substitute for South Africa’s domestically unpopular annual cash contribution to the Royal Navy.(19) Bourne firmly believed that expenditure should be directed towards local naval preparatory measures, in close consultation with the Admiralty, on the basis that the Union would bear the full cost of carrying out these services in time of war.(20)

In making his proposals to Government, Bourne repudiated any notion that a substantial South African navy was possible for the time being and rejected any scheme for a pseudo South African Navy. He contended that ‘it must be a real and not a sham South African Navy’.(21) Until South Africa’s human and financial resources increased, a South African Navy would be small and insufficient to cope unaided with the task of protecting the Union’s harbours and overseas trade.(22)

Sir Roland Bourne.

(National Portrait Gallery, London)

Based on the extensive groundwork of Bourne, the Union Government agreed to bear a portion of the costs for the further improvement and development of the Simon’s Town dockyard to complete the range of services available at the base. The Admiralty considered this to be first in the order of importance of the ways that the Union could assist Imperial naval defence.(23)

On the issue of local naval defence, Smuts and the British government reaffirmed the principle of separate dominion navies and agreed that South Africa's annual contribution to the Royal Navy would cease and that the Union would instead raise the nucleus of a small permanent seagoing naval service.(24) By this time, the Admiralty had accepted the principle that, rather than make annual contributions, each Dominion should provide for its own local naval defences and that all the Dominions, so far as their means permitted, should provide units which would form part of one empire Navy in time of war.(25) In doing so, South Africa was the last of the Dominions to cease its annual contribution.

The Union Government also undertook to considerably expand and reorganise the successful RNVR(SA) by increasing the General Service Section to up to seven companies, establishing a War Reserve Section, and forming a Minesweeping Section consisting of three flotillas for equipping and manning minesweeping trawlers for local defence in time of war. The minesweeping requirement was clearly influenced by the mining of Cape waters by the German raider Wolf in 1917. Moreover, the Union Government also agreed to assume responsibility for hydrographic survey of its own waters.(26)

As a result of the agreement reached at the 1921 Imperial Conference and subsequent exchange of correspondence, the British Admiralty agreed to make available to the Union, as a gift, the two relatively new minesweeping trawlers Eden and Foyle, and the new twin screw minesweeper Crozier which had been completed as a survey ship, but which could also be used as a minesweeper in time of war.(27)

To man these vessels, a new permanent arm of the UDF, the South African Naval Service, came into being on 1 April 1922.(28) The nascent service, together with the permanent instructional staff for the RNVR(SA), numbered sixteen officers and 148 ratings.(29) Although a large proportion of the personnel in the new service were initially seconded on loan from the Royal Navy, South Africa's own nascent navy was at last a reality and officers and men to man the ships and administrative headquarters were progressively recruited locally and enrolled in the RNVR(SA) on whole-time service with the SANS.(30)

Like the RNVR(SA), the SANS was placed under the command and administration of the British C-in-C Africa Station and its members were subject to Royal Navy discipline.(31) To assist the C-in-C with the increased administrative workload, it was agreed that 43-year old Commander N.H. Rankin, a retired Royal Navy officer, who was the Commander- Instructor of the RNVR(SA), would be loaned to the SANS and command the ships in a dual-hatted capacity.(32) With the title Commander South African Division, Rankin established his administrative headquarters consisting of general service, minesweeping, and hydrographic survey sections in three corrugated iron huts behind the old Arsenal in Simon's Town.(33) He officially assumed his duties on 1 April 1922.(34)

Commander N.H. Rankin

(Du Toit Collection)

As South Africa did not have its own naval base, the South African ships were based at Simon’s Town where workshops and storage space were made available by the Admiralty in the old West Dock-yard. Its personnel, together with those of the RNVR(SA), were initially nominally entered on the books of HMS Afrikander, the Royal Navy Depot Ship at Simon's Town.(35)

The new Service was formally established as a permanent unit of the reconstituted Union Defence Force along with the recently established South African Air Force from 1 February 1923.(36) However, as its personnel and its ships had been officially and continuously in service since 1 April 1922, this is the date recognised as the birthday of the SANS.(37)

To reinforce the legal position of the new service, the Admiralty agreed to loan the SANS a separate nominal depot ship on whose books all RNVR(SA) and SANS personnel could be borne subject to the regulations and discipline of the Royal Navy. To achieve this, the depot ship Afrikander was lent to the Union Government at no cost and commissioned as HMSAS Afrikander on 15 June 1923. On that date, the position of Commander South African Division became Officer Commanding South African Naval Service.(38) In practice, the administrative headquarters of the Officer Commanding SANS remained ashore in Simon's Town.(39)

Meanwhile, in July 1921, two additional RNVR(SA) units had been established at Port Elizabeth and East London. These units, together with those at Cape Town and Durban, were responsible for training sufficient men to man three general service divisions and three minesweeping flotillas comprising 36 officers and 600 ratings.(40A) War Reserve Section would follow in 1926.

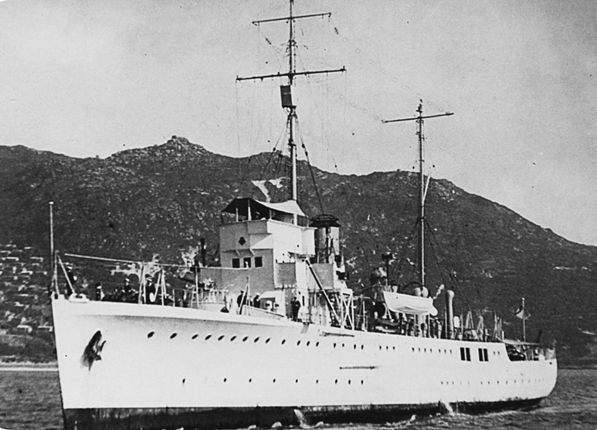

Eden and Foyle, which were to form the nucleus of the fledgling South African Naval Service, were standard units of the Mersey class of minesweeping trawlers, the largest of three Admiralty designs built during World War I to counter the extensive German mining threat.(41)

Both ships recommissioned at Devon- port on 15 November 1921 following refit and sailed for the Cape on 28 November 1921. As South Africa did not have enough qualified personnel to man its new ships on their delivery voyage, they were largely manned by Royal Navy delivery crews, augmented by eight members of the RNVR(SA). The highly decorated Lieutenant Commander A.E. Buckland DSO, DSC, RN, a mine- sweeping expert with considerable war experience, who was seconded to the SANS to head the Minesweeping Section of the RNVR(SA), commanded the senior ship Foyle, whilst Lieutenant L.E. Scott- Napier DSO, RN was in command of Eden.(42)

These two officers, together with seven other experienced members of their Royal Navy crews were seconded to the Union Government to assist with the creation of the new force. The remainder of the officers and men required to man the ships in South African waters were progressively recruited locally, and by October 1922, most of the RN junior ratings on all three ships had been replaced by South Africans, many of whom had previous sea-going experience.(43)

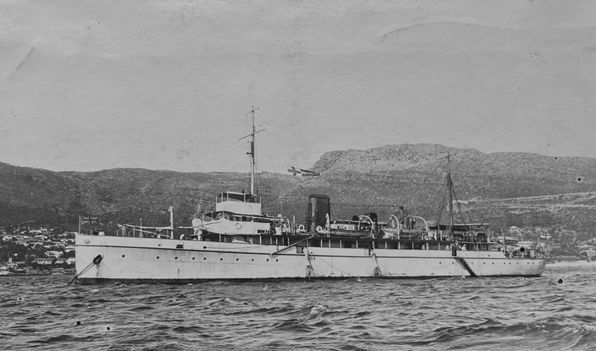

HMSAS Crozier at anchor in Simon’s Bay

with the Church Pennant hoisted.

(Du Toit Collection)

HM Surveying Vessel Crozier, which had also recommissioned at Devonport on 15 November 1921 for service in the fledgling SANS was under the command of Commander D.E. St M. Delius OBE, RN, a retired Royal Navy hydrographic surveyor from Cape Town. With a Royal Navy delivery crew, Crozier sailed for South Africa at the end of November in company with Eden and Foyle.(44)

The expansion of the RNVR(SA) and the arrival of South Africa’s first three ships was only a small beginning. Bourne’s hope and vision was that, in time, a Navy could be built up for the nation ‘that would be a credit to the Union’.(45) But first, the South African public had to become accustomed to the idea.

HM SA Ship's Eden and Foyle sailed from Simon's Town on 24 July 1922 for their first training cruise in South African waters. By this time, various names to connect the three new ships directly with the Union were suggested and rejected for one reason or another. It was finally decided in mid-1922 that the ships would be named after South African flowers. Eden and Foyle were renamed HMSAS Immortelle and HMSAS Sonneblom on 11 October 1922, whilst Crozier became HMSAS Protea.(46)

The newly renamed Sonneblom and Immortelle subsequently moved up and down the coast as the occasion demanded and were soon busily engaged mainly fulfilling their primary role of providing annual sea training for the members of the newly formed Minesweeping Section of the RNVR(SA). As a result, the ships soon became well known in all the major South African ports where they built up a reputation for smartness and efficiency.(47)

HMSAS Eden, pictured, and her sister

HMSAS Foyle,

were standard units of

the British Mersey class of Admiralty

minesweeping trawlers.

(SA Naval Museum)

Meanwhile, no time had been lost in preparing Protea for the immense task of surveying Union waters.(48) After Commander Delius left the SANS, Lt Cdr Dalgleish, her first lieutenant, assumed temporary command of the ship. Under his command, Protea commenced her hard-working career as a survey ship on the South African coast in October 1922, by which time most of the junior Royal Navy personnel in the ship had been replaced by South Africans.(49)

A proposal for the transfer of a sloop, at no cost, to modestly grow the small SANS was recommended by the Committee of Imperial Defence(50) in 1923.(51) This proposal was subsequently considered by the new ‘Pact’ government, led by General J.B.M. Hertzog.(52) But, at a time of global naval limitations and reductions, and with the far-sighted Bourne no longer Secretary for Defence, this was rejected on the grounds of a lack of funding to meet the operating costs and the matter was shelved.(53) Further consideration was given to the acquisition of a sloop in 1926(54) and again in 1930,(55) again without success.

The fledgling SANS was not, however, destined to proceed past phase one of its development as a Dominion Navy. In March 1931, during the Great Depression, which made it necessary to economise in every way, Hertzog advised the British Government that his government was considering discontinuing the hydrographic survey of South African waters, paying off the survey ship Protea and reducing the size of the SANS as a necessary economy measure.(56)

Budgetary constraints were not the only problem. Evidence clearly shows that there was also a distinct lack of interest shown by the mostly Afrikaans speaking senior UDF hierarchy, in having a navy at all.(57) They ‘had no special affinity to Britain or the sea’ and simply side-lined naval matters.(58) This was not helped by having no Naval Staff to advocate and advance maritime matters in Pretoria. Moreover, the Minister of Defence and leader of the Labour Party in the Hertzog coalition government, Colonel F.H.P. Creswell, believed that the land and air forces should enjoy a higher priority for extremely scarce defence funds.(59)

Meanwhile, as the depression deepened in 1932, all continuous training of Active Citizen force units across the UDF, including the RNVR(SA), was suspended as a further cost-cutting measure. As a result, training afloat in Sonneblom and Immortelle was suspended on 1 April 1932. By this time, the Defence Vote, and particularly that of the Naval Service, had come in for severe pruning.(60)

The sloop HMS Rochester entering

Simon’s Town in the mid-1930s.

It had

long been hoped that South Africa would

expand the SANS and acquire a sloop,

followed by a second as soon as

circumstances permitted.

(Simon’s Town Museum)

In October 1932, the Union Government finally made the decision to dispose of Protea as an unnecessary expense and to reduce the establishment of the SANS by almost two thirds from 164 officers and ratings to 56 from 1 May 1933.(61) The fall of the increasingly unpopular Hertzog Government in February 1933 led to the decision to defer the paying-off of Protea by one month while the new Coalition Government reconsidered its position. The decision was, however, upheld by the incoming ‘fusion’ government of national unity.(62)

With the paying-off of Protea on 1 May 1933, the total strength of the moribund SANS was reduced to just nine officers and 47 ratings.(63) Less than a year later, however, the Government decided that despite the drastic reductions already made, naval expenditure had to be reduced still further. As a result, both Sonneblom and Immortelle were paid off on 31 March 1934 after 12 years’ service, handed back to the Royal Navy, and their crews were mostly discharged.(64) This ended the Union’s initial attempt to maintain a small local naval service.(65) According to Martin and Orpen, South Africa had, for all its protestations of independence and Dominion status, ‘abdicated responsibility for her own defence at sea’.(66)

Although the small SANS had disappeared as a seagoing force, a small core permanent element was retained and Union Government funding of the RNVR(SA) continued.(67) The role of this much reduced organisation was twofold. Its first task was to train and administer the RNVR(SA) which with the return of national prosperity would grow and go on to provide the foundation for the wartime Navy and the permanent post-war Navy. Secondly, it was tasked with continuing the hydrographic survey of South African waters in modified form in conjunction with the Department of Sea Fisheries using the government fishery research ship RS Africana.(68) This small remnant of the SANS was to play an important role at the outbreak of war in 1939 and in the subsequent development of a permanent, credible, and enduring post-war navy for the nation, with an unbroken linage dating back to 1913.

NOTES

1 Allan du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships Past and Present (Rivonia: Ashanti Publishing, 1992), p. 5.

2 Roger Boulter, A Biography of F.C. Erasmus, South African Defence Minister, 1948-1959 (Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2012), p. 38.

3 Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, Third Edition (London: Fontana Press, 1991), p. 152.

4 The other four naval bases, which were all in British hands, were Dover, Gibraltar, Alexandria, and Singapore. See also Barry Gough, Pax Britannica (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), p. 36.

5 Chris Bennett, Maritime Defence in South Africa (Clareinch: South African Maritime Interest, 1998), p. 20.

6 Cabinet Memorandum on Naval Works Bill 1897, 11 January 1896, TNA: CAB 37/4.

7 Memorandum: SA Naval Forces and Base Establishments, 6 February 1951, South African Department of Defence Archives, Irene, Pretoria, hereafter DoD Archives: MVV/ Erasmus/Fouche Gp 1, Box 1, G/22, Simonstad.

8 Ian van der Waag, A Military History of Modern South Africa (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2015), p. 80.

9 Act No. 33 of 1907 Natal and Act No. 14 of 1908 Cape Colony.

10 Allan du Toit, ‘The Long Haul: The Evolution and Development of an Independent South African Navy’, in The Northern Mariner/Le Marin Du Nord/ Canadian Military History, From Empire In(ter)dependence: The Canadian Navy and the Commonwealth Experience, 1910-2010, XXIV/23, Nos. 3 & 4 (October 2014): p. 84. The South African Defence Act (13 of 1912), Sections 22 and 23, Establishment of the South African Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

11 Memorandum: SA Naval Forces and Base Establishments, 6 February 1951, DoD Archives: MVV/Erasmus/Fouché Gp 1, Box 1, G/22, Simonstad; C.H. Bennett and A.G. Söderlund, South Africa’s Navy (Simon’s Town: SA Navy, 2008), p. 17. 12 The South African Defence Act (13 of 1912), Section 23, Establishment of the South African Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

13 H. Giliomee, The Afrikaners: Biography of a People (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2003), p. 380.

14 Du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships, p. xxii; Du Toit, ‘The Long Haul’, p. 85.

15 Greg Kennedy, ed., Imperial Defence: The Old World Order, 1856-1956 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008), p. 133.

16 Estimates in the House of Assembly, General Smuts and Union’s Naval Policy, The Cape Times, 24 July 1920.

17 Secretary of Defence (Bourne), Empire Naval Policy and Co-Operation, 9 June 1921, TNA: CAB 21/187.

18 Jan Ploeger, ‘Uit die Voorgeskiedenis van die Suid-Afrikaanse Vloot: Die Ontstaan van die Suid-Afrikaanse Seediens’ Militaria, 3/1, 1971, p. 77.

19 Secretary of Defence (Bourne) Notes on Empire Naval Co-operation, 6 July 1921, TNA: CAB 21/187.

20 Secretary of Defence (Bourne), Empire Naval Policy and Co-operation, 9 June 1921, TNA: CAB 21/187.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Nicholas Tracy (ed.), The Collective Naval Defence of the Empire, 1900-1940, The Naval Records Society, Vol. 137 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997), pp. 137, 578.

26 Smuts to Lee, 2 August 1921, TNA: ADM 1/8612/167.

27 Du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships, p. 3.

28 Du Toit, ‘The Long Haul’, p. 86. See also Andre Wessels, Suid-Afrika Se Vlootmagte, 1922-2012 (Bloemfontein: Sun Press, 2017), pp. 17–18.

29 J.C. Goosen, South Africa’s Navy - The First Fifty Years (Cape Town: W.J. Flesch & Partners, 1973), p. 13.

30 Du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships, p. 3; Goosen, South Africa’s Navy - The First Fifty Years, p. 13.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid., p. 25.

33 Letter to the Editor from Commander C.C.M. Usher, OBE, RN, in The Naval Review, No. 3, 1970, p. 297.

34 Goosen, South Africa’s Navy - The First Fifty Years,p. 13.

35 Under the Dominion Forces Act 1911, Australia, Canada and New Zealand had adopted the Naval Discipline Act with the minimum of modifications to facilitate joint operations and ease of transfer between Imperial and Dominion ships, particularly in wartime. South Africa had not, however, taken any steps under the Act to administer its own naval discipline.

36 Proclamation, No. 17 of 1923, 26 January 1923.

37 Goosen, South Africa’s Navy - The First Fifty Years, p. 15.

38 Ibid., p. 13.

39 Du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships, pp.17-18.

40 Ibid., p. 3.

41 Ibid., p. 5.

42 Goosen, South Africa’s Navy - The First Fifty Years, p. 11.

43 Ibid., pp. 11-13.

44 Ibid., p. 11.

45 Eastern Province Herald, 25 October 1921.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 Du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships, p. 11.

49 Ibid.

50 The CID, originally established in 1902, was an important element in the framework of imperial security. Under the chairmanship of the British prime minister, it was an advisory body encompassing ministers concerned with foreign affairs and defence, and senior service person-nel. The real work of the CID was under-taken by several sub-committees, the most important being the chiefs of staff committee which had a collective responsibility for advising defence policy. Because of the CID’S advisory and consultative character, final defence decisions rested with individual governments.

51 Committee of Imperial Defence Paper

202-C, Empire Naval Policy and Co- Operation, South Africa, 18 July 1923, TNA: ADM 116/3438; Amery to Smuts, 5 November 1923, TNA: ADM 116/3438.

52 Bill Freund, ‘South Africa: The Union Years, 1910-1948 – Political and Economic Foundations’ in Carolyn Robert Ross, Anne Kelk Mager and Bill Nasson (eds), The Cambridge History of South Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 215. Labour ceased to be a major factor after the National Party won an outright majority in the 1929 general election.

53 Du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships, p. 4;

54 Goosen, South Africa’s Navy - The First Fifty Years, p. 16.

55 South African Naval Service Reorganization, 16 April 1931 and South African Naval Service, 26 January 1932, TNA: DO 35/267/6.

56 Despatch from Union Government to Dominions Office, 27 March 1931, TNA: DO 35/267/6.

57 H.R. Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces during the Second World War (1939-1945) (Simon’s Town: The Naval Heritage Trust, 2008), p. xi.

58 Ian van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge: Anglo-South African Relations, Dominion Nationalism and the Formation of the Seaward Defence Force in 1939-1940’,in Naval Digest No. 24, Anglo-South African Naval Relations 1936-1975 (Simon’s Town: Naval Heritage Society of South Africa, 2016), p. 53.

59 Goosen, South Africa’s Navy - The First Fifty Years, p. 13.

60 Goosen, South Africa’s Navy - The First Fifty Years, p. 16.

61 Du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships, p. 13.

62 Ibid., pp. 13-14.

63 Goosen, South Africa’s Navy - The First Fifty Years, p. 17.

64 Du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships, p. 13.

Union of South Africa, ‘Department of Defence, Report for the Year Ended 30th June 1934’,

30 June 1934, p. 4.

65 Ibid.

66 H.J. Martin and N.D. Orpen, South Africa at War, South African Forces World War II, vol. VII (Cape Town: Purnell, 1979), p. 5.

67 In 1937/38, out of an approximate revenue of £42 million, the South African Defence vote was £1,666,090, of which the sum of £45,450 was devoted to the naval services, principally the RNVR(SA).

68 Du Toit, South Africa’s Fighting Ships, p. 4.

About the author

Allan du Toit retired from the Royal Australian Navy in 2016 after over 40 years’ service in two navies. He entered the South African Navy in 1975, later transferring to the RAN in 1987. He commanded HMAS Tobruk during peacekeeping operations in Bougainville, the Australian Amphibious Task Group, the multi-national maritime interception force enforcing UN sanctions against Iraq, Combined Task Force 158 in the Persian Gulf, and Border Protection Command.

Allan du Toit

He also served in a wide range of single-service and joint appointments ashore including Deputy Chief of Joint Operations, Head of Navy Capability and Australian Military Representative to NATO in Brussels. The author of three books on the SA Navy, Allan has written and lectured on historical and contemporary naval affairs in Australia and abroad. He is a graduate of Stellenbosch University and the University of New South Wales where he received his masters degree and doctorate and is an adjunct senior lecturer. Allan served as President of the Australian Naval Institute from 2011-13.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org