The South African

The South African

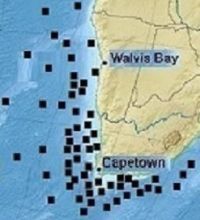

The Second World War is generally divided into two periods. The first is from September 1939 until November 1942, when Germany was on the offensive. The submarine offensive started in October 1942, succeeding in sinking 14 ships around the Cape of Good Hope in three days with some 26 in total up to November 1942 [Kleynhans, 2018b]. One U-Boat sank 3 merchant ships on 8/9 October 1942 approximately 100 km off Cape Hangklip. The ship losses off the South African coast between 1939 and 1945 were no fewer than 155, of which 134 were from U-Boats [Bizley, 1993]. A further 20 ships had been captured and sunk by German Surface Raiders [1939-1942] and two had been damaged by mines laid by German ships. The total sinking results were an approximate 5.88 merchant vessels sunk per U-boat [Kleynhans, 2018b].

Figure 1. Location of ship sinkings from Submarine activity around South Africa

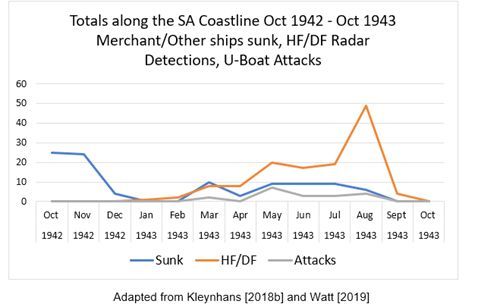

The second period from December 1942 until the end of the war, the Allied countries were on the offensive. The operational conditions in the South Atlantic, and more notably off the coast of South Africa, had indeed changed drastically since October 1942. The Union Defence Force [UDF], and the Allies had adopted several defensive anti-submarine measures, which were aimed at curtailing the losses of merchant ships around the South African coast. The South African response changed the nature of the coastal threat as depicted in Figure 2 below.

The following represents a synthesis of events and people that include the Artillery Specialists [ASWAAS], as well as the Special Signal Services [SSS] at radar stations drawn from several publications [Brain, 1993; Chetty, 2006; Crook, 1990, 1993; Harris, 2017; Harrison, 2019; Kotzé, 2021; Lloyd, 1990; Mangin & Lloyd, 1998; Weideman, 2004b].

WAAS AND WAAF

The WAAS [Women Auxiliary Army Service] was established on 10 May 1940, together with the WAAF [Women's Auxiliary Air Force] [Kotzé, 2021]. A popular myth is that women in the Union Defence Force [UDF] served in clerical and administrative capacities only. This was certainly not true of the Artillery Specialists [ASWAAS] nor the women who served in the Special Signal Services [SSS]. They were the only women that served as active combatants in the British Commonwealth during the war [Kotzé, 2021; Weideman, 1998a]. They made a significant contribution by alleviating the alarming manpower shortages of the Union at the time.

Figure 2 Adapted from Kleynhans

The prevailing oath of secrecy imposed at the time continues to prevail even to this day. One ASWAAS girl recalls that having taken the oath of secrecy, she was not even allowed to tell her grandmother about the nature of their work.

Pam Friedlander wrote, “‘What made it so special was that we were on our honour nor to talk: about anything we did. We gave our word, while others had to sign things” [Crook, 2013, p. 164]. Because radar was also such a closely guarded secret, SSS girls were also forbidden to talk to anyone about the type of work they were doing. Once enlisted, the girls kept to this oath belying the popular belief that no 182 Military History Journal Vol 19 No 4 June 2022 woman could keep a secret. Indeed, they did [Brain, 1993].

Figure 3: SSS Doreen Russell

Image: Harris

Artillery Specialists (ASWAAS)

Long periods of inactivity in the coastal artillery could be boring for younger men who had requested for a transfer to more active units. The loss of artillery specialists prompted the deployment of women. Captain Airey of the Coast Artillery was instrumental in the decision to use enlisted WAAS women at the coastal batteries though there was some doubt about their suitability for such units [Crook, 2013].

Mackenzie-Hoy [2009] recalls her mother’s experience during WWII in 1941 as an ASWAAS gun layer when she was 20. This is the aiming on land, in air, or at sea, against surface or aerial targets. She joined the army and went to Robben Island for training with most girls under 24. She recalls that her mother and a 24 year-old Lt Geoff Daniels were on a shoot which was to aim at a target towed by a radio-controlled tug. Daniels changed the sights left, by 500 yards, and they missed the target and blew the tug out of the water at 12 miles. They all had their leave stopped and (as the story goes) the battery commander gave Daniels a coconut.

Figure 4: ASWAAS Lance Bombardier

Mary “Bunty” Moir

Image: Crook

Figure 5 Steenbras Coastal Battery, Gordons Bay [Image by author]

They had to learn to operate all the technical instruments pertaining to the guns, give the relevant orders and produce data that enabled the guns to engage targets, as well as operating the actual 9.2” and 6” guns.

Some 18 became officers, 31 Staff Sergeants and 49 Sergeants. The remainder were Bombardiers and Lance Bombardiers. Although the ASWAAS uniforms included the usual Artillery badges and buttons, they were not allowed to wear these badges until June 1942. As a sign of their acceptance as full members of the Coastal Artillery [despite initial opposition to wearing artillery insignia] the ASWAAS were permitted artillery badges and buttons [Weideman, 1998a].

They also served in North Africa as the only women Gunners in the British Commonwealth. The women of ASWAAS had signed on for duty anywhere in Africa and were thus allowed to wear the appropriate orange flashes on their epaulettes, see Figure 6.

Private Marjory Hill, a mathematics teacher, enlisted in the WAAS as a driver, was accepted in the ASWAAS and was commissioned later as Captain as the only female artillery officer in the UDF. She retired as Officer Commanding the ASWAAS. As OC of the ASWAAS she was awarded the King Commendation on 8th of June 1944 for valuable services in connection with the war [Crook, 1993].

The ASWAAS regarded themselve as an elite group. The ASWAAS and SSS did however work together. In Durban a small vessel was tracked by the SSS when breaching the limit regulations. They concentrated only on the vessel and working with the ASWAAS artillery, they trained their guns and sent a warning shot across its bows. The effect was a hasty, right-angled turn to head for the open sea to comply with harbour regulations. This may have been the first time the SSS worked with the ASWAAS artillery. As the ASWAAS was always considered the frontline combatant girls, the SSS being secretive they proved themselves as instrumental for the ASWAAS to depend on them as combatant peers [Brain, 1993, p.77].

Figure 6 Uniform buttons and orange flash

Visual watches were referred to as “Look-Outs” and were conducted on a basis of four hour shifts 24 hours a day. “We were on duty an hour before sunrise for ‘Stand To’, running through routine drill and procedures and we ‘Stood Down’ an hour after sunset” [Lance Bombardier Mary ‘Bunty’ Marr in Crook, 1993, p.166]. Usually, they were on duty for eight days, with two days off. After lunch every day, they would also have two hours off. Weideman [1998a] writes about the ASWAAS girls watching seals sunning themselves and schools of whales from the BOP [Battery Observation Post]. When on duty they were not allowed to use words like “ship” and “shipping” for security reasons and had to use code words like ‘a block of flats’ when referring to a large cruiser.

Special Signals Service [SSS]

Many accepted WAAS recruits also ended up in the South African Signals Service (SASS). Late in 1941 recruitment officers were informed that a new secret unit attached to the SASS, needed women recruits. This unit eventually became known as the Special Signals Service [SSS] that was officially established on 11 December 1942 [Crook, 2013]. The SSS division of the SASS was a comparatively small specialist unit not linked to any other military force. By December 1944, when it was fully staffed, the SSS comprised 1621 personnel in total.

| Total | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1621 | 969 | 507 | |

| Officers | 145 | 11 | 28 |

| Other | 1476 | 852 | 479 |

Figure 7: Captain (later Major) Nancy Blue.

Nancy Blue, an efficient and attractive young woman who had already enlisted in the WAAS, was recruited by her uncle, Colonel Collins of the S.A. Corps of Signals [Brain,1993].

Nancy Blue as the OC WAAS of the SSS, was impeccably dressed all the time and served as a perfect example of how one should look in uniform. Sadly, Captain (later Major) Nancy died at quite a young age soon after the war ended and a plaque commemorating her in the SSS has been set into a wall at the Bernard Price Institute [Brain, 1993].

Recruitment efforts appealed to youth, glamour, vitality, and adventure. Military service was portrayed as a place of glamour and femininity where women would learn poise [Chetty, 2006]. Cynthia Stanford coined the term ‘finishing school for young ladies’ [in Brain, 1993, p. 103].

The use of glamour and femininity which made its appearance in the Hollywood films of the era was the persuasive factor in the recruitment of women for the war effort. In an article penned by a female recruiting officer and aptly titled “The Recruit is Precious”, women who decided to enter military service were, from the outset, portrayed as being at the centre of attention at parties.

Figure 8 Corporal M Beauchamp,

Special Signal Services

Figure 9 Lt P Eaton

Chetty [2012, p.126] displays a photograph, 'Corporal M Beauchamp, Special Signal Services’ of a young smiling woman, her curly hair barely held in check by her cap. It accentuates both youth and femininity and follows the convention of the portrait with her looking into the distance with the light falling on her face. These conventions are also apparent in another photograph simply titled 'Lt P Eaton'. Here the figure appears more reserved, and her pose heightens the glamour of the figure, drawing strong parallels with the Hollywood actress publicity shots of the 1930s and 1940s, serving both to glorify women's roles in the military as well as to emphasize their femininity.

Recruitment produced 36 women for the first SSS women's course, which commenced in February 1942. Upon appointment, their first day was devoted to collecting their uniforms from the Union Grounds. The letter of one radar girl, Patsy, describes how their kitbags were full of shoes, greatcoats, and the rest to carry. The men watching them drag their kitbags with commented that they must shoulder them, ‘since they asked for it’.

They were issued with everything, down to toothbrushes. They had to accept everything or get nothing in its place. The shirts and skirts were respectable, but the tunics awful. The girls were exempted from having to accept the thick, greenish-khaki stockings and voluminous bloomers to match. Later they learned that these were dubbed 'passion killers' by the army girls. The uniforms included the usual badges and buttons of dull bronze which meant that there was no polishing of brass buttons to be done. Their working clothes consisted of khaki slacks, a windbreaker, a shirt, a peaked cap, and a gas mask. Heavy coats were a must, particularly in the icy cold and wet winter. The Dress Uniform included a khaki tailored shirt and Jacket. The uniforms were rather ill fitting, and as a result had to be tailored [Brain, 1993].

Apart from the university degree initially called for, temperament and background were important factors, since they would be working long hours, often in lonely and isolated places, and would need to be able to get on well with one another while doing so [Brain, 1993].

Basic training included squad drill and the intensely vigorous PT [physical training] performed on the lawns around the swimming pool of the University of the Witwatersrand.

The result is that they are women now who command attention by their fine bearing and physique [A Male Drill Instructor Thinks - "Drilling Makes a Girl More Attractive", in, Chetty, 2006, p.117].

Male instructors had concerns about how to cope with the women, treating them exactly like they treated male soldiers.

Figure 10 Squad Drill Image: Brain 1993

They refrained from calling them angel or girlie or anything like that since as soldiers they did not walk from place to place, but marched yet they took to it like ducks to water. One non-commissioned officer on one occasion, promptly ordered a young girl with too much make-up to “reduce the camouflage”. One girl recalled men called them “Blue Eyed Monkeys” for no explicable reason, with another who really hated training “these bloody women”. Notwithstanding this, Doreen Russell [nee Harris, course 2 in May 1942] noted that military men treated the SSS women with respect.

From February 1942 to February 1945, a total of 28 six-week courses took place [Brain, 1993].

The “Anywhere Oath”.

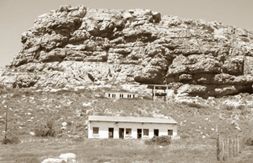

In most cases the radar stations located around the coast were positioned on remote hilltops frequently inaccessible by road, e.g. Figure 11.

Much discussion took place as to whether it was better to be posted to a station or to 'Freddie' - not that they were given a choice! Those working in 'Freddie' had an overall picture of what was happening throughout the region, whilst those at a station knew only what was showing up on their own screen. 'Freddie' girls [Harris. 2017] worked closely with Combined Ops, and were often privy to secret information about ship sinkings and tonnages, the detection of U-boats, aircraft losses, etc. Such information, being totally secret, only reached the stations long afterwards, if ever. They also had all the city amenities to draw upon during their hours of leave, whilst remote station operators usually lived at isolated outposts in an unspoiled environment, with sea and empty beaches on their doorstep [Mangin& Lloyd, 1998]. Some recall that it was usually a wrench moment when a 'Movement Order' from HQ instructed them to pack their kitbag and ‘ditty box' and report to another station [Brain, 1993].

Figure 11 Elands Bay

[Image: Daniel van Niekerk, 2019]

Radar girls recall that shifts were boring when no echoes were detected. Lloyd [1990] remembers that she never picked up an enemy submarine, but on occasion some other stations did. Despondency might set in being isolated, wasting months of their lives, growing older by the day, while the never-ending war dragged on. Some coped better than others with this.

Shifts could however be very busy when much shipping was passing round the Cape. Sometimes during a shift too much was happening on the screen to allow the set to be turned off for the routine morning maintenance and the technical staff would have to wait until the radar girls had contacted Freddie with their information.

After or before night shifts, the operators would sleep in a small building next to the tech hut. With the station operating 24 hours a day a typical operator 5hr shift duty schedule looked like this:

| Tuesday | 1800-2300 | ||||||||||||

| Wednesday | 0800-1300 | ||||||||||||

| Thursday | 2300-0300 | ||||||||||||

| Friday | 1300-1800 | ||||||||||||

| Saturday | 0300-0800 | ||||||||||||

| Sunday | Day off | ||||||||||||

| Monday | Day off |

The most unpopular and most dreaded watch was the middle watch [from 2300 to 0300]. Middle Watch meant being woken up in the middle of the night, often in the freezing cold winter. As a result, the girls would sometimes sleep fully clothed, on top off their beds, so that they would be ready when the duty-driver arrived. One could never catch up the broken sleep. The best watch, on the other hand, was from 0300 to 0800 since this was usually followed by two days off. One watch would be sleeping in preparation for night duty. Another watch would be on actual visual watch duty. The watches were called the green, blue, red, white, and yellow watches respectively. These watches came on duty in rotation, so that other chores could be undertaken by a watch not actually on watch. This always left one watch about to have a day off and one watch about to go on shift. At Hangklip, with sea and empty beaches on their doorstep, white sand and good surf was a few minutes away. The radar girls would walk through a strip of bush and over a few low dunes, down to the sea. Some walked down the long road from the Silversands tech site, after a 0300 to 0800 shift, to swim in the rock pools.

As fully fledged members of the UDF they were more than just “pretty girls” doing their bit for the nation’s war effort in their own eyes [Kotze, 2021].

Figure 12: Pringle Bay Beach circa 50’s.

Image: John Logan

The military service allowed them an opportunity to participate in a historical event of an entire generation -a narrative that allowed them to experience adventure and excitement and from which they were unwilling to be excluded. [Chetty, 2006].

Figure 13: Far right in this photograph:

SSS Betty Minnie Booker stationed

in Betty’s Bay radar station in 1943

[Trained in 1942]

During the war, these ‘intrepid’ women [Crook, 1993, p.156] made themselves quietly very useful. Despite the tedium and the consistent concentration required by the work, there was the satisfaction that they were preventing shipping disasters and saving lives. Notwithstanding the morale and sense of responsibility of these dauntless girls in often isolated postings far away from civilisation, they lived a happy-go-lucky life at the stations [Crook, 2013].

Figure 14 Gavin and Leslie Lundie at

Betty’s Bay Barracks

[Feb 2022]

Gwen Williams maintained that at that time 'people liked to belong to things like that'. She said in an interview done many years ago: 'For many of us it was the most important time of our lives, a time when were most enthusiastic and impressionable’ [Crook, 1993, p. 164].

In 1942 'Tinker' Brink quit school at 16, lied about her age and was recruited into ASWAAS. In 1984 she disclosed that “We felt we had to do something for the war effort and by joining the artillery I felt I was being very useful' [Crook, 1993, p. 164].

Joining other like-minded recruits and their subsequent military experiences they were transformed into mature, capable, and responsible women.

“They were very special times” [Pamela Friedlander in Crook, 1993, p.164]

Mary “Bunty” Mart [in Crook, 1993, p.165] stated “...an experience I was lucky to have had.”

Betty Addison [SSS] ... all over the world almost all were involved, and you were missing something if you didn't go into it and I've certainly never regretted it” [in Chetty, 2006, p. 283].

Figure 15 Margaret Elizabeth

(Betty) Addison néé Wallace [SSS]

on her centenary in November 2021.

Although most of these women have passed on, Margaret Elizabeth (Betty) Addison celebrated a century of memories on 18 November 2021. Betty was born on 8 June 1921. After high school she obtained a BA degree at the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg. At the age of 20, she joined the special signals unit [after completing Course 1 in February 1942 as Wallace, M.E. "Betty" (later married Addison). She was one of the first people to work with, and even to know the existence of radar. She recalls being moved to several secret locations around the South African coast during the war years. (Figure 15.)

“O quam cito transit gloria mundi”

[Oh how quickly the glory of the world passes away]

[Alexander V in Pisa, 7 July 1409].

These recollections express regretful recognition that something has ended as all things eventually do.

This overview illustrates that military accomplishments do not depend primarily on the resources and size of an army but also on the courage and fortitude of the people who served in it.

References

Bizley, [1993/94] U-boats off Natal. The Local Ocean War, 1942-44. Natalia,23/34 76-98

Brain, P. [1993]. South African radar in World War II. The SSS Radar Book Group.

Chetty, A. [2012]. Imagining National Unity: South African Propaganda Efforts during the Second World War. Kronos, 38, 1.

Chetty, S. [2006]. Victory Was Our Defeat: Race, Gender, and Linerlism in the Union Defence Force, 1939-1945. Doctoral dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban.

Crook, L. [2013]. Island at war. Naval Heritage Trust. South Africa.

Dooner, C.R. [Capt. SAN ret]. [2019]. The Cape Fortress Coast Defence Artillery Fire Control System in The Second World War: A presentation to the Cape Town branch of the SA Military History Society.

Harris, L. [2017]. The Special Signal Services (SSS) Women and Native Military Corps: Operators and Guards at the WWII Secret Radar Stations of the Western Cape, South Africa. CORIOLIS, 7 [2]

Kleynhans, E.P. [2018b] The Axis and Allied Maritime Operations around Southern Africa, 1939-1945. Doctoral Dissertation, Stellenbosch Uniuversity

Kotzé, E.M. [2021]. More Than Just Pretty Girls in Uniform: A Historical Study of Women’s Military Roles during World War II. Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch University.

Lloyd, S. [1990]. Life on the RADAR Stations: An Operator’s View. Online Access http://samilitaryhistory.org/diaries/radarshe.html

Mangin, G. and Lloyd, S., [1998]. The Special Signal Services (SSS) ’Shield’ in Military History Journal, 11(2), http:// samilitaryhistory.org/vol112ml.html

Mackenzie-Hoy. [2009]. My mother’s exploits during WWII. Online Access

Weideman, M. [1998a]. Robben Island: Coastal Defence, 1931-1960. MA dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Weideman, M. [2004b]. Robben Island’s role in coastal defence 1931-1960. Military History Journal, 13(1),Online Access

Image references to internet sites have been omitted since the search engines do not retain the actual image references which can therefore change on a daily basis.

About the Author

Wim Myburgh resides in Pringle Bay, Western Cape. He is an amateur historian with an interest in WWII radar and coastal defence events around Pringle Bay as a place of historical value with special reference to women, who played a part in protecting allied ship convoys around the Cape.

He is an industrial psychologist by profession and holds a D Phil from NMMU. He uses a statistical theory called ROC (receiver operator characteristics) in his work and was fascinated to find it had its origin in the radar signals of WWII where signal to noise separation was critical.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org