The South African

The South African

Part one of this three-part article appeared in the December 2021 Military History Journal, Vol 19 #3, while the whole article is on the internet at www.samilitaryhistory.org

Introduction

The Eastern Force commanded by Colonel Berrangé, one of the four forces of the Union Defence Force that participated in the South-West African campaign, had its advance base camp at Kuruman, 350km from the South-West African border. From Kuruman, it first had to cross the uncharted, waterless Kalahari desert to reach Rietfontein at the border, which presented a formidable challenge. From here, its orders were to secure the region between the border and the Keetmanshoop to Windhoek railway line to remove the threat of enemy attacks from the east later in the campaign. A previous paper described the recruitment of the 2 000 mounted troops and support staff at Kimberley, Vryburg, Kuruman and Mafeking, their convergence on Kuruman and the elaborate preparations for crossing the Kalahari and the rest of their campaign.(1) Most of these actions took place hastily during the month of January 1915, as the Eastern Force was only formed on 4 January 1915, after the other three forces had already been formed. This paper picks up in early February 1915 in Kuruman, at the time when Berrangé was ready to start despatching his troops over the dreaded Kalahari, up to their arrival and consolidation at the border town of Rietfontein at the end of March 1915.

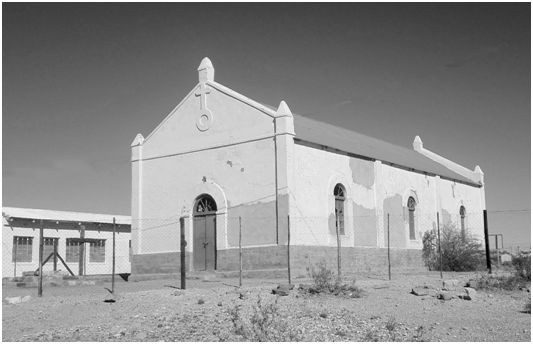

Figure 1. The old missionary church

at Rietfontein in 2019.

(Johannes Haarhoff)

Rietfontein at the South-West African Border

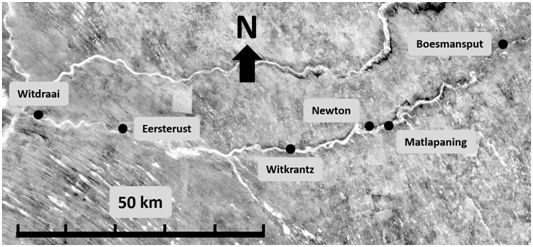

The village of Rietfontein was the only village on its line of march through the Kalahari before the Eastern Force would enter enemy territory. It held a strategic position less than 5 km from the border with the “loneliest and most isolated police post in the Union” and a magistrate’s court. Closely associated with Rietfontein was the adjacent police post at Witdraai, about 50km to the southeast, depicted in Figure 2.

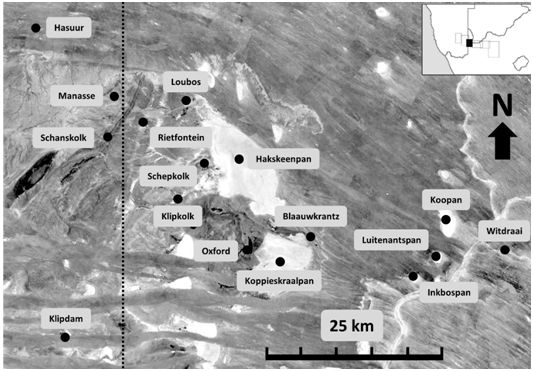

Figure 2. The area between Witdraai and the border.

Witdraai, at the start of the 20th century, was a hub where the main roads and routes at the time converged, luring illicit dealers in arms, ammunition, stolen cattle and alcohol. In 1907, the Cape Mounted Police at Rietfontein established a small police post with “three camel men and one native detective” at Witdraai.(2) By 1909, the Witdraai police post gained permanence when the staff were moved from tents to huts. It had a strong well with good water, dug earlier, which offered the first permanent water supply point for the Eastern Force after its crossing of the Kalahari. On the other side of the border, directly opposite Rietfontein, the enemy had a post at Schanskolk, as well as a stronger enemy garrison at Hasuur, a short distance to the north.(3)

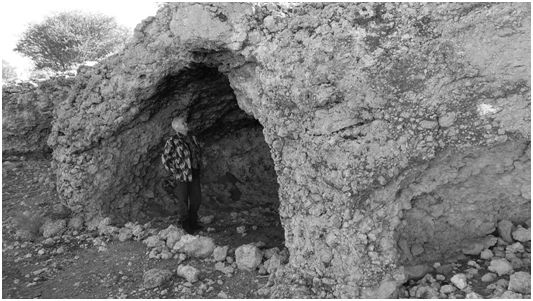

Figure 3. Witdraai is also known for its

“caves” in the riverbank,

where camels probably rested during the heat of the

day, shown here in 2019.

(Johannes Haarhoff)

An Enemy Raid into Union Territory

On 8 February 1915, while the Eastern Force was training at Kuruman and the supply depots in the Kuruman River were being established, the commander at Hasuur, Oberleutnant Goedecke, swung into action by crossing the border to occupy Rietfontein. After a skirmish which left casualties on both sides, the enemy captured the resident magistrate, Mr Stewart, and some others.(5,6) Munro’s patrol managed to escape and retreated via Oxford to reach Witdraai on 10 February with the enemy in hot pursuit. A further skirmish followed where Rifleman A O’Brien, Scout Harry Bok of the Camel Section and some camels were captured by the enemy.(7) Munro and the remainder of his patrol escaped again and retreated further, this time halfway back across the Kalahari to reach Witkrantz on 16 February, where a water boring section was at work. They were exhausted after their strenuous escape with long periods of sleepless vigils, without much water or food. Convinced that they shook off their pursuers, they were surprised to be surrounded by an enemy patrol as they were recovering beside two water tanks.(8) During the short fight that ensued, Captain Munro and Riflemen Clarke and Foreman were captured near the spot shown in Figure 4. A further scout was wounded, one native scout was killed and three camels shot. The water boring section was forced to retreat to Boesmansput.(9)

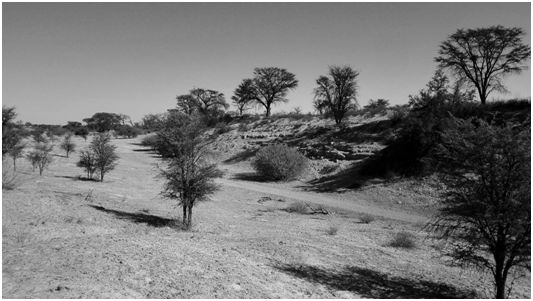

Figure 4. The Kuruman River at Witkrantz in

2019,

at or near the spot where Captain Munro

was captured.

(Johannes Haarhoff)

The enemy patrol turned back to Rietfontein, destroying some of the water boring equipment along the way, burning the Witdraai and Rietfontein police stations and blocking the well at Witdraai. This daring enemy raid drove all the smaller parties of the Eastern Force back to Matlapaning, upsetting the elaborate plans for water boring and the setting up of advance depots. Berrangé called upon the Kalahari Horse to reclaim the Union territory now under enemy control. After leaving Kuruman, they left strong detachments to guard each depot and post, allowing work parties to return to their work. By the end of February, two weeks after Munro’s capture at Witkrantz, a patrol of the Kalahari Horse under Captain Dickason was the first to reach the deserted police post at Witdraai. They quickly cleaned out the well and used waterproof sheets to form improvised water troughs for their horses and themselves. The route from Kuruman to Witdraai was now secure and the rest of the Kalahari Horse could move forward to join Captain Dickason. Next to arrive was a squadron under Major Frylinck, followed by the balance of the Kalahari Horse under Lieutenant-Colonel van Zyl.(10)

The Battle of Rietfontein

Now being at full strength at Witdraai, the Kalahari Horse proceeded to clear the enemy from the remaining area towards the border. Van Zyl sent two squadrons to establish camps at Klipkolk on 14 March and Schepkolk on 15 March respectively. The next day, enemy troops under Capt Schoepfer arrived from Keetmanshoop to reinforce the Hasuur garrison.(11) The enemy realised that they should strike at the Eastern Force before the camps at Schepkolk and Klipkolk could be further reinforced. On 18 March an enemy company left Hasuur for Rietfontein.(12) While Schoepfer improved the defences in and around Rietfontein, he sent an enemy patrol of 250 men to attack the camp at Schepkolk. The squadron of 90 strong under Captain van Vuuren stood firm and by nightfall the attack was called off and the enemy fell back to Rietfontein, suffering some casualties.

Early the next morning, on 19 March, Captain Van Vuuren and his squadron counterattacked the 200 enemy soldiers at Rietfontein. Schoepfer entrenched part of his force in the hills at Sannaspoort near the border to command the road between Rietfontein and Hasuur, while other troops defended Rietfontein. At first, the enemy could not be dislodged from Rietfontein. Van Vuuren then encircled the enemy at Sannaspoort, attacking them in the rear at 13h00. The enemy in the village withdrew to Sannaspoort and the combined force retreated after a while to their base at Hasuur. By 14h00, the Kalahari Horse had complete control of Rietfontein and the area up to the border.(13) In the Official History of the Great War, the action at Rietfontein was one of four by the Eastern Force singled out: “In view of the importance of the water at Rietfontein and the enemy superiority in numbers, Captain van Vuuren may be considered as having operated in a highly creditable manner.”(14) The casualties of the Eastern Force were one killed (Trooper Baden- horst who died the following day at Rietfontein) and two wounded (Troopers Slabbert and Viljoen).(15) The enemy retired with the loss of their transport and a number of horses, four killed, 20 wounded and two captured on the field.(16)

The battle of Rietfontein ended the enemy occupation of Rietfontein and a large part of the Kalahari, which lasted from 8 February to 19 March. The entire route from Kuruman to the border was now secured. The enemy had retreated to Hasuur, where Captain Schoepfer had orders to detain the Eastern Force as long as possible to allow the main enemy force to withdraw in an orderly way from Keetmanshoop.

The March to Witdraai

The route from Kuruman to Witdraai had two distinct parts. From Kuruman to Boesmansput, although the sand was heavy, there were convenient spaced depots and a direct communication line to Kuruman. The second part from Boesmansput to Witdraai was the dreaded “Thirst Belt” with no regular water supplies, shown in Figures 5 and 6. Two artificial water points had to be established; at Newton (replenished from Boesmansput with sedan cars) and Eersterust (replenished from Witdraai by ox-wagon). This fragile arrangement had to cater for both the regular transport convoys, continuously running up and down, as well as the once-off passing of the mounted horsemen.

Figure 5. Route map from Boesmansput to Witdraai.

Good communication and discipline were essential to keep the numbers of troops and ox-wagons at every post within the limits of available water. To maintain the orderly progression of the convoys, each depot had to notify the base at Kuruman as soon as its storage tanks were filled to capacity. When all stations were ready, the order was given to all convoys, limited to a maximum of five wagons, to move. The full convoys moved one station forward and the empty convoys moved one station back, with the “regularity of clockwork”.(17) This system worked well most of the time and it became somewhat easier as time went on with more water drilling successes along the route. The mounted horsemen, travelling one squadron at a time, similarly had to await permission to move to the next post.

On 3 March, just after the Kalahari Horse had reached Witdraai, Berrangé started to despatch the 5th SAMR and 9th BMR from Kuruman, the last troops leaving on 8 March. Cullinan’s Horse stayed in Kuruman to escort an artillery battery and ammunition convoy that were only despatched by the end of March. From Kuruman to Boesmansput, the troops moved at a more leisurely pace to save their horses for the Thirst Belt and allowing more time to arrange for water and supplies further down the route. After Boesmansput, it took an average of three days of hardship to cross the Thirst Belt. The first troops left Boesmansput around 16 March. Hereafter the rest of the squadrons followed as quickly as the water supplies would allow, with regular arrivals of the squadrons at Witdraai from 19 March to 12 April. Between these dates, when the movement of the mounted horsemen was superimposed on the regular transport wagon traffic, the Thirst Belt experienced its heaviest traffic.

Figure 6. The Kuruman River at Newton in 2019.

(Johannes Haarhoff)

It became seriously congested and the supply of water, both at Newton and Eersterust, was wanting for short periods.(18) For the South-West African campaign, the military planners worked on daily allowances of 6.8 litre (1.5 gallon) per man; 32 litre (7 gallon) per horse; and 45 litre (10 gallon) per head of cattle.19,20. These allow us to estimate how much water was required at each of the two intermediate water stations at Newton and Eersterust:

The fleet of 40 sedan cars had to work hard to meet this demand at Newton. The cars worked together in pairs and the drivers had to fill and empty the drums themselves.(21) A sedan car could carry one drum of 270 litres (60 gallons) at a time, which suggests that 16500 / 270 = 61 car trips had to be made each day. About 30 cars, each making two round trips per day, were required keep abreast of the demand. Other than keeping the tanks at Newton filled with water, the cars also supported the ambulances, postal system and despatch work.(22) By the end of March, when almost all the mounted riflemen were at Witdraai or beyond, the congestion of the Thirst Belt eased somewhat and 22 of the sedan cars moved west to Witdraai to take on new roles in support of the Eastern Force. An anonymous trooper “EL” recalled:

So far as water was concerned, motor cars conveyed a small supply to a spot about halfway through the desert. The cars had enormous distances to travel over hard country, but their efficient services saved our horses and ourselves. We shudder to think what would have happened if the motor transport had failed us. But we plugged on towards Witdraai and when we got there, we hadn’t one spare horse left. That tells its own tale. The horses had been giving up all along the route, utterly worn out. We arrived at Witdraai three weeks after leaving Kuruman. We shall remember those three weeks.(23)

The animals

The animals suffered badly. Even the best cattle, with adequate grazing, could not deal with the exceptionally heavy stretches of sand, day after day. A transport officer pitied the animals “knee deep in loose and burning sand. As the heat at this time was fierce and blinding, the distress and suffering of the animals attempting to cross it can be more easily imagined than described”. Relief for the animals was sought by reducing wagon loads by a third to 1 800kg while simultaneously increasing the number of oxen from 16 to 18 or even 20 per team – further complicating the management of the convoys through the Kalahari.(24) The loss of horses during the hardships at the Thirst Belt was unavoidable. It was found that smaller horses were hardy and withstood the strain remarkably well better than “larger and more showy animals”.(25)

The conditions were no better for the mounted horsemen - heat, cold, dust, disappointment when insufficient water was found at water points, and their horses’ suffering were their constant companions. The troops were not issued with greatcoats; some nights were very cold. On one occasion, rum was distributed to the troops; on another, a convoy had to make multiple stops at night to allow them to make large fires to warm themselves.(26) Trooper “EL” again:

We ... never have encountered such dust as this. It was not the wind that caused the mischief: the dust was so fine that when our horses’ feet went into it, it rose in powdery billows like white snuff. At times it was so dense that the horse’s tail in front of one was obscured and there was only a vague suggestion of an outline of the man. The dust was taken in with every inspiration and found its way inside veils and goggles, till eyes and nostrils, teeth and tongue, were clogged. This dust demon was our daily companion right through to Witdraai and not only filled the men’s lungs and eyes, but caused the horses double discomfort, for the poor beasts had to breathe it and see through, and the continual pounding on the soft yielding stuff affected their feet.(27)

From Witdraai to the Border

West of Witdraai, the Kuruman River turns away from the line of march. The Eastern Force therefore had to leave the Kuruman River and head to Rietfontein through open country. The area between Witdraai and Rietfontein is dotted with pans, which fortunately held water after the exceptionally good summer rains. Some squadrons followed a northern route along Koopan, Hakskeenpan and Loubos. The southern route taken by the others went along Luitenantspan or Inkbospan, Blaauwkrantz, Koppieskraalpan, Oxford, Klipkolk and Schepkolk, shown in Figure 2. Following the good rains, some of the pans still held some water, but hard sunbaked mud along the edges formed level, smooth surfaces – to the delight of the sedan cars who had to battle with deep Kalahari sand before. One officer described the moment:

After the loose, heavy, heart-breaking sand, shut in on all sides by sand dunes with scarcely a breath of air to relieve the sweltering heat, one can hardly describe the glorious sensation of feeling oneself in the open, on a decent hard road. So, opening the throttles of our cars, we sent them rushing through the air at the rate of 40 to 45 miles an hour. After seven miles of this exhilarating enjoyment we arrived at Oxford farm, where there is a fine dam of fresh water and good wells, providing a generous supply for man and beast.(28)

The joy of finding open water was equally appreciated by a mounted rifleman:

Imagine our feelings, after all we had gone through, to come to a farm called Oxford, where, joy of joys, we discovered a magnificent sheet of water! Did our dust- grimed eyes sparkle at the sight? Did we enjoy it? Well, as our transatlantic friends would say: it was some swim! It made new men of us.(29)

The Eastern Force, after its long trek across the Thirst Belt, showed visible signs of the hardships of the crossing. A trooper recorded his observation a few days after reaching the border:(30)

The smart regiment that marched out from Kimberley would not have been recognised in this tattered, torn, and ragged crowd that rested at Hasuur. Our clothing was in a deplorable condition. Many were without boots and even breeches, and it was a common sight to see such unregimental articles as trousers, hats and boots which had been picked up at different homesteads, the discarded garments of enemy soldiers. We were only allowed to carry one blanket and macintosh, and as it was very bleak and cold it will be understood that it was no joke to try and sleep with one blanket over one and a howling wintry wind trying to tear that off.

During the last week of March 1915, the 5th SAMR and 9th BMR joined the Kalahari Horse at Rietfontein, bedraggled and worn down by their arduous trek of about three weeks across the Kalahari. This brought the first phase of their campaign to successful completion, now ready to enter enemy territory as a fighting force. The final paper in this series will follow the military activities of the Eastern Force for its final six weeks, until it was disbanded on 11 May 1915.

Endnotes

1 Haarhoff, Johannes. Berrangé’s Trek: Assembly and Preparation of the Eastern Force for the South-West African Campaign in Military History Journal, Vol 19, No 3, Dec 2021.

2 Abbott, Henry and Van Zyl, Kobus. Camels to Cruisers: 100 Years of Police Adventure in the Kalahari, Witdraai Centenary Album 1907-2007. Durban: Just Done Productions, 2018, p. 33.

3 Dane, Edmund. British Campaigns in Africa and the Pacific 1914-1918. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1919, p. 50.

4 Riekert, Donald W. Verby die Groot Stormloop. Unpublished biography of General JA van Zyl, completed in 2009 and made available privately by Erika Riekert in 2019, Chapter 47.

5 King, CES. Unpublished report from the Transport and Remount Department Office of the Eastern Force to Colonel Berrangé dated 29 July 1915. Copy in Transnet Heritage Library, Johannesburg, p. 7.

6 Rayner, WS and O’Shaughnessy, WS. How Botha and Smuts Conquered German South West. London: Simpkin Marshal Hamilton Kent and Company, 1916, p. 130.

7 Department of Defence Documentation Centre. 5th South African Mounted Rifles Diaries. Pretoria, in WW1 GSWA Box 20.

8 Witkrantz was not one of the initial water points on the Thirst Belt. It is likely that this was the site where one of the boring parties tried unsuccessfully to drill for water, therefore the presence of the water tanks.

9 Berrangé, CLA. Report on the Formation and Operations of the Eastern Force in German South-West Africa up to 15 May 1915. Copy in Department of Defence Documentation Centre, Pretoria, in WW1 GSWA Box 20.

10 King, CES. General Berrange’s March Across the Kalahari, Royal Colonial Institute Journal, 1919, Vol. 10, p. 150.

11 Riekert, op. cit. Chapter 48.

(br)12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Government Printer. Union of South Africa and the Great War: Official History. Pretoria: 1923, p. 54.

15 Berrangé, op. cit. Petrus Johannes Badenhorst is buried in the Rietfontein Village Cemetery.

16 Government Printer, op. cit. p. 54. These numbers are at odds with those provided by Von Oelhafen, Hans. Der Feldzug in Südwest 1914-1915. Berlin: Safari-Verlag, 1923. Von Oelhafen stated that only one of the enemy was seriously wounded and died later in Windhoek. The Von Oelhafen numbers were provided to the author by Harald Koch from Windhoek.

17 King, General Berrange’s March, op. cit. p. 150.

18 Riekert, op. cit. Chapter 48.

19 Kleynhans, Evert. A Critical Analysis of the Impact of Water on the South African Campaign in German South West Africa, 1914-1915. Historia, 2016, Vol. 61 No. 2.

20 King, Unpublished Report, op. cit. p. 10.

21 Government Printer, op. cit. p.57.

22 Berrangé, op. cit.

23 “EL”. Kimberley to Keetmanshoop: A Record March Across the Kalahari with the 5th SAMR. The Nonquai 1915 Vol. 4 No. 1 p. 25.

24 King, General Berrange’s March, op. cit. p. 151.

25 King, Unpublished Report, op. cit. p. 10.

26 Department of Defence Documentation Centre. Cullinan’s Horse Diaries. Pretoria, in WW1 GSWA Box 20.

27 “EL”, op. cit. p. 25.

28 King, General Berrange’s March, op. cit. p. 152.

29 “EL”, op. cit. p. 25.

30 Ibid.

About the Author

Johannes Haarhoff is a retired civil engineer with a lifelong interest in the history of technology, particularly how industrialisation has changed the course of South Africa. He volunteers most of his time towards the digital preservation of the rich historical sources of the Transport Heritage Library in Johannesburg and the Graaff-Reinet Museum in his hometown.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org