The South African

The South African

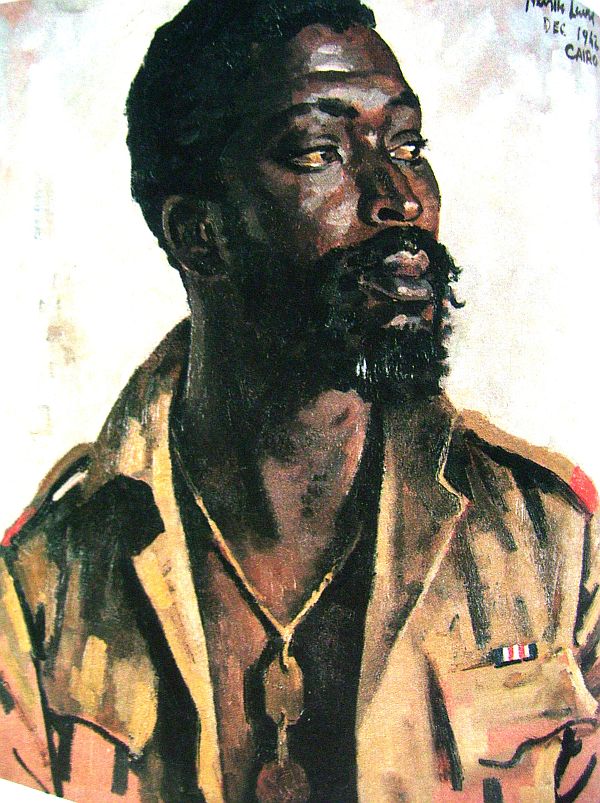

Portrait of Cpl Job Maseko painted by war

artist Neville Lewis in Cairo 1942

Courtesy Ditsong National Museum of Military History

On 8th April, 2021, the British newspaper Daily Mail published a report that a petition would be submitted to Britain’s Government under the following heading “The hero snubbed for being black: Petition is launched to award Victoria Cross to South African WWII hero who snuck(sic) aboard Nazi ship and blew it up with bomb he built from a tin of condensed milk - but was denied medal due to his race.”1

The text goes on with the following assertion “British generals nominated Job Maseko for a VC, but his South African commanders found the idea of a black man receiving such a prestigious medal ahead of his white peers alarming”.

The report continues “Instead, he was awarded the Military Medal - the lowest bravery honour at the time - for his 'ingenuity, determination, and complete disregard of personal safety' after he sank the German ship in Tobruk harbour in 1942.”

The Mail adds “Now a Somerset man, Bill Gillespie, is fighting to right what he sees as a massive injustice and has started a petition. Job used his experience as a miner before the war to make the bomb himself - out of a tin of condensed milk, a long fuse and gunpowder”.

The rather brief petition omitted factual data that might support the request for awarding a posthumous Victoria Cross. The names of the British generals supposed to have recommended the award the Victoria Cross are not mentioned. The South African commanders alleged to have stopped the award of the VC are not identified either. There are also some factual errors.

The petition was rejected in 2021 and a British Parliamentary publication online explains the petition’s rejection simply as: “It’s about honours or appointments,” and “We only reject petitions that don’t meet the petition standards”.2

Corporal Job Maseko was among the soldiers of the 2nd SA Infantry Division taken Prisoner of War on the 21st of June, 1942, when Major-General H.B. Klopper, surrendered Tobruk to German commander, Generalleutnant Erwin Rommel. Of the 10 722 South Africans 1 200 were Native Military Corps soldiers.

The 1929 Convention on the treatment of POW, allowed fit Other Ranks to be made to work and Maseko and others were set to unloading German cargo vessels in Tobruk harbour and this gave him an opportunity to sabotage a ship.3

His pre-war experience with explosives at the Daggafontein Wes Gold Mine enabled him to assemble a small explosive device, using a milk tin, a roughly made fuse 36 feet long, and the propellant taken from cartridges, always to be found on the ground where soldiers had dropped them. He carried the bomb in his haversack until his work led him into a German freighter moored at the dockside and laden with petrol drums and jerry cans. When he lit the fuse at the end of a working day fellow prisoners, including Andrew Mohudi, Sam Police, and Koos Williams, distracted their German guard with conversation. After the POW had returned to the camp where they were held, they saw black smoke rising from the docks and then heard explosions. The next day the POW were briefly questioned about smoking on board the ship but denied smoking. Later Maseko and another escaped from the POW camp and after 23 days of walking through the desert they were picked up by an armoured car and returned to the South African forces.

Allegations that senior South African officers blocked the award of the VC have often appeared in the media and in some politicians’ speeches. All appear unaware that after recommendations commenced on the level of the SA forces in the Western Desert, they would proceed to higher British commanders to be recommended to the King via the War Office authorities and usually a board of officers.

A search for reliable evidence of what was written about the award of the Military Medal to L/Cpl Job Masego, revealed nothing of value. The assertion that he had been refused the award of the Victoria Cross appeared to originate in the autobiography of South African official war artist Neville Lewis, Studio Encounters. The book contains no supporting information. Lewis did not identify any source for his allegation or first-hand evidence.4 He briefly mentions an outline of the events perhaps told him by Maseko while sitting for his portrait. Lewis expressed his opinion that Maseko should have received the VC. But then he went on to blandly add the allegation that Lance-Corporal Job Maseko was blocked from receiving a Victoria Cross because “he was only an African”.

Neville Lewis might have been an able artist, but he was no historian nor was he on the Army’s General Staff. Though a soldier during the First World War, he really could have known nothing about processing recommendations for decorations for bravery.5 His story betrays complete ignorance of the attention and care given by Colonel H.O. Sayer, Deputy Director Non-European Army Services, to checking Maseko’s statement and how few VCs were awarded to South Africans. Besides, citations are always kept secret to avoid disappointment if the award is refused and the Corporal would not have been told of any recommendation.

In 2017, research in the SANDF’s archives included time spent examining the file which contained the original citation for an honour.6 Though notes made at the time were kept they are not now to be found. Reliance must therefore be placed on memory.

The file in the Defence Force archive shows that after Maseko was questioned, as was usual with an escaped POW, every effort was made to find evidence of what he had done. Col H.O. Sayer, who had to recommend the citation to the next level of command, believed the account given by the courageous Corporal. As citations for decorations for bravery require evidence, Sayer took Maseko to Tobruk to indicate where he remembered the cargo ship had been moored. A diver found the ship. Though the Germans had dragged it away from the dock, it was close to where Maseko indicated. The diver found sufficient evidence to confirm that there had been a fire in the German ship. Maseko’s description of the Germans’ reactions suggested that that they had suspected carelessness but not sabotage. Maseko and his companions were thus not suspected, and they were not closely interrogated. His planning and executing the sabotage was ingenious and courageous and he certainly deserved recognition. There can be little doubt that if the Germans had suspected sabotage Maseko and his companions would not have survived. The enemy’s failure to investigate the sinking thoroughly suggests that Maseko was not in direct or immediate danger, and it would have been very difficult to make a case for the VC.

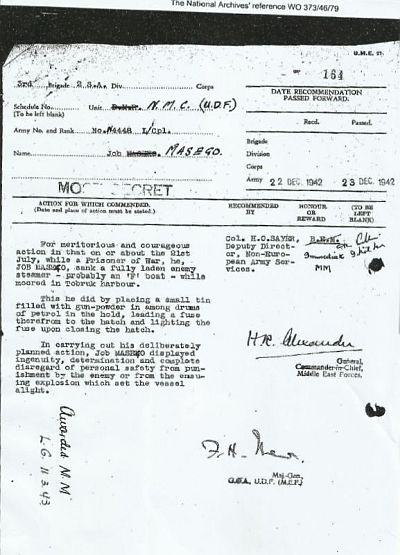

Copy of recommendation from theBritish National archives.

The signature at the top right is next to “BEM” crossed-out “immediate MM” below that.

Moreover, the file in the British National Archive shows that Maseko was initially recommended for the British Empire Medal, but someone named Cilliers, probably Col. Harry Cilliers, the GSO1 on Maj-Gen Theron’s Staff, had crossed out ‘BEM’ and recommended “immediate MM” instead.7 Despite its ‘floral’ title the BEM was awarded “in recognition of meritorious civil or military service”. The Military Medal instead was for "acts of gallantry and devotion to duty under fire". This means that, far from downgrading the award for Maseko, a more appropriate honour had been recommended. Given that the MC and MM were usually awarded for gallantry under enemy fire, the MM seems the highest decoration that would have been appropriate for Maseko's action.

The citation, recommending the award of the Military Medal to Job Maseko, reads as follows:

For meritorious and courageous action in that on or about the 21st July, while a Prisoner of War, he, Job Masego, sank a fully laden enemy steamer – probably an “F” boat – while moored in Tobruk Harbour.

This he did by placing a small tin filled with gunpowder [sic] in among drums of petrol in the hold, leading a fuse there-from to the hatch and lighting the fuse upon closing the hatch.

In carrying out this deliberately planned action, Job Masego displayed ingenuity, determination, and complete disregard of personal safety from punishment by the enemy or from the ensuing explosion which set the vessel alight.”

The citation, finally signed by General Sir Harold Alexander, GCB, Commander-in-Chief Middle East Forces, after endorsement by South African Maj-Gen Frank Theron, does not contain a recommendation for the VC or show that such award was mentioned or objected to by anyone at any level of command. The normal practice then, as now, is that citations for honours for bravery would travel from the original authority to the highest authority in the field to receive final approval by the British Sovereign, George VI. Alterations to the recommendation could not have been made by South African commanders after a British general had recommended the award of the VC. Citations would not have originated with British commanders, but from the nominee’s unit or, in the case of escaped POW, from the authority debriefing the soldier, such as Colonel Sayer and Major Fred Rodseth who wrote out Cpl Maseko’s statement for him. The history of the VC shows that amendment for or against could be made and were made by War Office authorities in London.

During the Second World War the conditions set for Awarding the VC which had often been changed since it’s institution in 1856, were “... the Cross shall only be awarded for most conspicuous bravery or some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy”. The Military Medal was awarded to warrant and non-commissioned ranks for gallantry in action against the enemy.

L/Cpl Job Maseko was decorated with

the Military Medal by Maj-Gen F.H. Theron, CB, CBE

Maseko’s award was published in the Supplement to the London Gazette, March 1943, pp.1176 and 11767 No. 190382 and read:

“The King has been graciously pleased to approve the following award in recognition of gallant and distinguished service in the Middle East: No N 4448 L/Cpl Job Masego(sic) – Native Military Corps.”11

Despite what Neville Lewis and others implied the Military Medal was not an inferior medal but a distinguished honour, following immediately after the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Frankly, the allegation seems offensive to the integrity of the officers who processed the recommendation, to the Military Medal, to others who earned it – and to Corporal Maseko himself.12

During the Second World War with more than 400 000 South African volunteers on military service, and whoever it was recommending the Victoria Cross and approving the award, only five Victoria Crosses were awarded to South Africans. Two were serving in the British Army - Lieut Gerard Ross Norton VC, MM, originally from Die Middelandse Regiment and later transferred to the the Hampshire Regiment; and Warrant Officer George Gristock VC, Royal Norfolk Regiment. A third was Squadron Leader John Dering Nettleton VC, serving in the Royal Air Force. Only Sergeant Quentin Smythe VC, Royal Natal Carbineers and Major Edwin Swales VC, DFC, SA Air Force, seconded to the RAF, were in South African units when they performed their acts of bravery. Smythe, and Gristock (whose VC was awarded posthumously) and Norton were under personal and direct enemy fire. Nettleton led a Lancaster bomber raid on a German submarine engine factory in Bavaria. Four of his six bombers were shot down, but he and the remaining bomber bombed the target though hit by antiaircraft fire. Swales's aircraft was attacked by a Messerschmitt-110 after a bombing raid in Germany. Two of his aircraft’s engines were destroyed. He tried to reach friendly territory and ordered his crew to bail out. He crashed alone in northern France and his VC was awarded posthumously.

Incidentally, this author’s research also revealed that when a recommendation for the award of the Military Medal to Sergeant Lucas Majozi was submitted to Colonel Jack Bester he took into account that during the Battle of El Alamein, Majozi continued through the first night leading stretcher bearers evacuating wounded under enemy fire and himself wounded and fainting from loss of blood. Bester drew a line through the letters “MM” and in his own hand wrote in “DCM” which was duly awarded.13

Portrait of Sgt Lukas Majozi painted by

war artist Neville Lewis in Cairo 1942

Courtesy Ditsong National Museum of Military History

Only one member of the SA Naval Forces was awarded the Naval equivalent of the DCM. The Conspicuous Gallantry Medal was awarded to ’... Chief Petty Officer Stoker R. Sethren, who though wounded eleven times, continued firing a machine-gun at a German plane attacking HMSAS Southern Isles until it fell in flames.”

It is rather sad that after flattering the subject of the portrait he painted, Lewis went on to invent an allegation for which evidence has not been found, against officers of the Union Defence Force’s command that they deliberately denied deserved recognition to the courageous soldier. It is equally sad that so many years after the War, after Maseko’s death and after Lewis’ book was published, that the unwarranted allegation continues to circulate and cause sensation and serves as a toy for politicians. After the way in which Black soldiers had been treated in the Great War – strict segregation in Europe, the failure to award campaign medals to them because of disagreements as to responsibilities between the Defence and the Native Affairs Departments, one cannot be surprised that Lewis’s story may be a further source of mistrust and anger among Black people.

To the uninitiated assessing brave acts of soldiers might seem quite easy. Maseko might indeed have qualified for the award of the VC. His act risked personal danger. But it is extremely difficult to interpret and judge the levels of bravery described in the Warrants that institute honours for bravery. Comparing what Maseko did with the actions of the five servicemen who did receive the VC and the sailor who received the CGM suggests that while he acted in the presence of the enemy, he was notionally, but not directly, in danger.

Unfamiliarity with the procedures and problems of citing courageous service personnel continues even today to lead the well-meaning to believe Neville Lewis’s distorted story, ignorant as he was of the procedures of recommending and approving bravery awards when soldiers perform actions that endanger their lives.

NOTES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A long interest in matters military, led Deon Fourie to introduce and teach the subject of Strategic Studies at the University of South Africa for some 30 years until 1998.

He served in the Citizen Force from 1950 retiring as a Brigadier-General in 2007.

He consulted for the Department of Defence and other institutions, including the NATO Defence College in Rome and drafted Presidential Warrants for new decorations for the Defence Force.

He published on military subjects, and lectured at military colleges and research institutions in Europe, the United Kingdom, the USA, Taiwan and Latin America in South Africa.

His publications include "The New Decorations and Medals for the SA National Defence Force" in the British Journal of the Orders and Medals Research Society (September 2006).

He holds South African decorations for merit and was made a Grand Cross of the Venerable Order of St John of Jerusalem by Queen Elizabeth II in 2021

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org