The South African

The South African

Muriel married Lt.-Col. E.W. Benson in June 1916, though within 24 hours of the wedding he had to return to France. She never saw him again. Kitty Eckersley’s husband was killed on the Somme while she was carrying their first child: “I felt I didn't want to live. I had no wish to live at all because the world had come to an end for me. I had lost all that I loved."[1]

Vera Brittain lost all four of her closest friends, one after the other: first her fiancée Roland, then Geoffrey, who comforted her through her grieving for Roland, then Victor, wounded and blinded, who died unexpectedly just hours after she had decided she would marry him out of pity, and lastly her brother, always close, killed on the Italian Front in the last months of the war. Little wonder that even by 1920 she could still end a yearning poem by crying out: “But who will give me my children?” And the roll call of pain goes on almost endlessly: the struggle to survive and keep her family together after her husband died of wounds during the war was too much for Anna Pöhland’s undernourished body; and she succumbed to lung disease in 1919, leaving five orphaned children without means of support ...

Vera Brittain in her VAD uniform during the war.

The overwhelming weight of books on the First World War concern themselves with its military aspects, a goodly number with the political posturing and manoeuvring of the “frocks”, and not a few with the work (and disruption) of the home fronts. But very few address the broken hearts and struggles of the women – the mothers and sisters, wives and sweethearts – left behind and left bereaved. Jay Winter (quoted in Jalland) has estimated that the war left from 3 to 4 million widows in its wake, and it is this group in particular – especially the working-class element – that this article looks at.

Of course, not just widows were grief-stricken. In France, for example, about three million immediate next of kin were impacted by a military death, and in total an average of over ten relatives for every fallen soldier – 14 million separate griefs. A wider spreading of the net computes that by 1919, two-thirds of the entire French population was affected by one or more losses. For the UK, an estimate is that 3 million Britons lost either a son, brother or other close relative, and that a wider spreading of the net would encompass virtually the whole population.

WOMEN’S STATUS

Fundamental to a discussion of Great War widows is an awareness of the edwardian woman’s station in life. However much they may have been privately cherished, they were, on the whole, regarded very much as second-class citizens. They rarely had the vote; they were expected to reflect their male relatives’ opinions, they were regarded as not capable of managing their lives – practical or financial – without male guidance. So pervasive were these attitudes that the majority of women internalised this view of themselves. That their education (if they had any at all) was usually much inferior to that of their menfolk only accentuated the situation. In short, the edwardian woman – across the whole of Europe – lived largely in a state of ‘dependence’, while patriarchy reigned supreme (albeit under attack).

The combination of socially imposed dependence and lack of literacy forced many freshly widowed working-class women to seek support and advice from their local authority figures – often priests or minor civic personages. Inevitably, these would be socially conservative individuals far more likely to advise submission to fate and to existing, usually rather meagre, channels of support, than to encourage the active pursuit of self- supporting independence. In this way the widow was often locked into a permanent state of social inferiority and dependence.

BECOMING A WIDOW

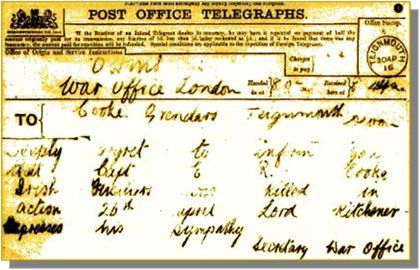

In Britain the arrival of that small brown telegram envelope would crystallise a long-lurking fear into awful reality. Doorstep scenes could be so distressing that those delivering the telegrams would sometimes knock and run away, despite that being quite against their instructions. The telegram would be followed by a form letter giving a few more facts (if known). Yet sometimes communications served only to prolong the dread: the loved one was not known to be dead but was only “missing”.

The dreaded telegram -

“Deeply Regret To Inform You …”

So, was he wounded and being cared for in some obscure place? Was he a prisoner? Had he got separated from his comrades and was even now finding his way back? Further news, good or bad, might take many months or even years to filter back to the fearful wife or family. They would oscillate without surcease between hope and dread, comforting themselves perhaps with spiritualist mumbo-jumbo, clutching at every slender hint of new information. (In The Living Unknown Soldier Le Naour gives a moving account of how slender hopes could remain alive for years.[2]) Official notifications provided almost no details beyond place and date of death (and perhaps not even that little). In some countries – Russia for example – a common soldier’s death would not usually be notified at all; relatives might learn of it two or three years later from death lists published on the initiative of a newspaper.

But if the news was the worst, many widows would want to know all the details of their husband’s death as a way of bonding as closely as possible with his last moments, and as an aid to closure. Yet taciturn officialdom and sensitive comrades usually withheld or distorted the truth (even if it was fully known – many of the army’s dead just ‘disappeared’ in a shell burst or in the shambles of an attack). Private communications frequently gave conventional, anodyne accounts – “he did not suffer”, “he died bravely”, even if the victim had actually squirmed and screamed through three days of agony with his stomach half blown away. Such communications were of questionable help, especially if later information overturned the story and laid bare the deception. Similarly the often long-delayed return of personal effects, though ultimately becoming, perhaps, treasured mementos, inevitably twisted the knife – especially if their state (blood stains, bullet holes) provided vivid evidence of the moment of death.

BEREAVEMENT & MOURNING

At the time of the Great War, mourning generally followed well-established routines, both highly visible and usually prolonged. Yet prevailing realities imposed or at least encouraged major alterations to ‘the old ways’. In the UK the conventions were more easily cast aside by educated women than by working-class widows, for whom giving the deceased “a good send-off” was the right and proper thing to do. Failure to do so risked inviting imputations of callousness or even infidelity. (Of course, only those who died on the home front, or in a home-based hospital, could literally be given a ‘send-off’, but the phrase encapsulates the desire to do as much as possible of the ‘proper thing’ for the deceased.) But this was the very class who could least afford to follow nineteenth century rules of special costume and ceremonial – given that it was likely to have been a family breadwinner, perhaps the sole one, who had died. Hence, almost as soon as the war began, conflict arose between mourning and cost, a conflict that often further burdened the widow already coping with the agony of loss.

Loss of a loved one induced a sense of disorientation and loneliness. Rouzeau & Becker [3] describe the new widow as undergoing “an individual ordeal experienced in dreadful solitude” and that once the condolences have been respectfully spoken or written, “the bereaved are alone ...T”. Compounding this sense of isolation was the attitude often encountered, in at least Anglo-Saxon societies, that prolonged or excessive mourning was somehow unpatriotic, and that widows should rather display dignified and composed stoicism. Inevitably, as a consequence of this call to patriotism, women’s sorrow was sometimes mixed with bitterness.

Some widows – in France and Italy for example – took to wearing their mourning ostentatiously, despite government disapproval, to show their resistance to the war and to encourage pacifist emotions. After the war, such behaviour in Germany was increasingly regarded ambiguously: on the one hand extended periods in mourning dress and social withdrawal were considered appropriate for bereaved women, on the other the pacifist, war-rejecting undertones of such behaviour fed into the ‘stab-in-the-back’ myth that so energised Germany’s military revival during the 1930s. More generally, in fractured or uncertain countries – Italy and again Germany are examples – extended and visible mourning was to some extent regarded as antithetical to the task of post-war nation-building. In post- revolutionary Russia recognition of war widows was practically non-existent. Not merely was any reference – in the widest sense – back to the Tsarist capitalist war of 1914-17 strongly discouraged, but its social impacts were in any case largely eclipsed by the mass death traumas of the years that followed the revolution.

Bodies of soldiers killed overseas were not usually returned for burial in their home country during the war. Postwar, in the face of strong pressure from the bereaved, some countries, such as Italy, Belgium, and France, relaxed this policy. In the latter about one third of the identifiable bodies (representing only about 15% of the total dead) were returned to families for private (re)burial. In these countries, of course, bodies of the dead were often relatively close to their homes. There was much controversy in the United States but in the end families were permitted to bring back their dead for reburial and two-thirds did so, although officially the practice was discouraged as far as possible.

Where repatriation did not take place, widows who lacked the means to travel to the war cemeteries being established on the battlefields had no ‘site of remembrance’ to visit: hence the ubiquity of war memorials throughout Europe, ranging from neighbour-subscribed plaques recording the dead of a single street or community to large town memorials listing hundreds of names, and surmounted by an expensive bronze sculpture. Less helpful (one assumes) to the grieving were the many civic projects labelled as ‘Memorials’ – cottage hospitals, cricket pavilions, rose gardens and the like. Several countries ran free or subsidised travel schemes to help family members – naturally including widows but not usually the poorest – to visit distant cemeteries. The US Federal Government ran a generous scheme to sponsor trips by female relatives to visit the graves of those American soldiers whose bodies remained in France. In selecting who was entitled to the benefit, ‘maternal loss’ was often accorded a highest status than widow-hood. The scheme continued to operate even during the Great Depression, indicative of the regard in which the country held their grieving women; the cosseting lavished upon the travellers also reflected paternalistic assumptions about female fragility and delicacy.

Whether these visits were more traumatising than cathartic for the bereaved is difficult to say; an ex-soldier who took tours out to the trenches reported “It hurts to see the women who come here hoping to find graves, walking about reading other people’s crosses and crying a bit”.[4] However, their grief seems to have been more manageable than that of French widows whose husbands were classified as “missing”: numbers of them were seen in the war’s immediate aftermath roaming the battlefields “madly exhuming bodies they thought they recognised”. The dead buried on more distant battlefields such as Salonika, Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, and Palestine were mostly visited by no-one but the cemetery caretakers.

In societies where religion (such as Islam) dictated strict funeral rituals involving the dead person’s body, families had to come to terms not only with their grief but with the truth that twentieth-century warfare only rarely delivered their soldier’s body back to them – if indeed there was any recoverable body at all. Thus closure derived from the performance of traditional rites was denied, and new dispensations had hurriedly to be devised and laid down.

Visiting a grave

Some Belgian widows endured a special kind of harshness during the war: if their loved one had been regarded by the occupiers as a “franc-tireur” (a label rather liberally applied) most mourning and commemoration procedures by the widow were banned. In Dinant, where resistance was (or was considered to be) especially egregious, such widows were even refused the right to use coffins. The Germans were more accommodating, even helpful, in the case of fallen soldiers.

FINANCES

For the great bulk of war widows, loss of their husband meant a descent into financial hardship, if not actual destitution. Succour could come in the form either of a pension or charity.

Charity: In contrast to the sense of entitlement surrounding widows’ pensions and allowances, there was a widespread abhorrence of “charity”: seeking such help represented the ultimate loss of self-respect. The ultimate depths of deprivation and poverty would often be endured before tentative steps – frequently prompted by the needs of the widow’s children rather than by her personal distress – would be taken to seek assistance. Yet there was much charity to be had in all belligerent countries, even if ultimately it was inadequate to meet every need. And charity frequently came with strings attached. In Britain and Germany, and elsewhere in various guises, the need for charitable support was determined in many cases by the “Lady Visitor”, who subsequently would also monitor its ‘proper’ use by means of regular follow-up visits. ‘Improper’ use (or behaviours) could lead to even closer supervision – even to withdrawal of the support. Those in need were generally working class, and those with sufficient time on their hands and the necessary ‘do-gooding’ motivation to be “Visitors” would be middle to upper class: each one a stranger to the other, living in worlds as different as chalk from cheese. While Visitors at one end of the scale could be genuinely caring and empathetic, many would be appalled at the conditions – physical and moral – that they encountered. It was a situation ripe for disapproval and resentment to flourish in mutual antipathy.

The situation did not materially change once government pensions for widows were introduced; if anything, the volume and variety of visitations increased, with anonymous accusations (or clear evidence) of slovenliness, immoral behaviour, poor parenting, wasteful spending, and other infractions of ‘acceptable standards’ obliging the police, local clergy, inspectors from pensions authorities, and other civic officials to investigate. Where modest ‘guilt’ was established, on-going official surveillance intruded on the widow’s home life; where the offence was more radical – and immorality (as then defined) topped that list – the pension could be stopped, permanently.

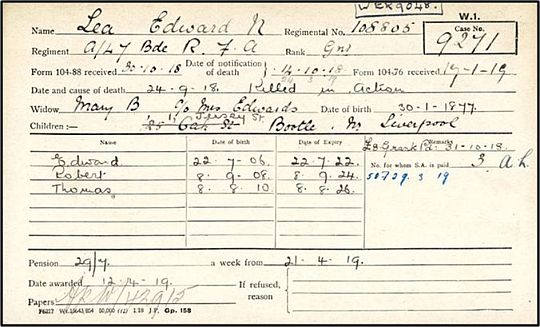

Pensions: Most belligerent countries established pension schemes for soldiers’ widows. In the UK and in Germany, at least, it was made clear this was in recognition of the deceased’s service – not in acknowledgement of his widow's needs. Likewise, the pension amount was rank rather than needs based, though additional sums per dependent child were often part of the package. Pensions were generally meagre; in Germany, for example, the widow of a private soldier received about one quarter of a skilled worker’s wage. Charities endeavoured to supplement this, but as in the UK, charity came with intrusive monitoring. One alternative to seeking charity was finding a job, though this would be difficult for a widow with children to look after. Another solution was to remarry – but this usually resulted in cancellation of the pension.

A UK Pension award card. Note the gap

between the date of death (24 Sept 1918)

and the first pension instalment (21 Apr 1919).

Note also the amount: £1. 9s. 7d. (or £1.48)

for the widow of a gunner (equivalent to a private)

with three children between 9 and 13.

Austria-Hungary was another case where charities supplemented meagre pensions, but both here and in Germany, as the war went on and life became more difficult and more expensive, public donations on which the charities depended dried to a trickle and their ability to offer support diminished accordingly. By 1920 the burden on Germany (as with other countries) was immense, with just over half a million widows receiving financial support – in addition to 164,000 parents of soldiers, and 1.13 million orphans. (This, of course, is far from the full picture, since it excludes those not qualifying – by virtue, usually, of independent income – for support; and almost invisible to history are the relatives of those many thousands who died on the home front from starvation and deprivation.) Things grew worse, for during the Twenties hyperinflation gripped both Germany and Austria. The bulk of ‘pensioned’ widows, their lives already hollowed out by grief, thus teetered on the brink of (or fell into) destitution. Schemes for settling widows and their families in healthful rural areas, and for establishing childcare institutions foundered on the sheer numbers involved.

PRESSURISING WIDOWS

Post-war, all the principal belligerents encouraged their widows to re-marry – as soon as possible. It was represented to them as a duty, either to have more children (to restock the depleted populations) or to ensure that existing children would have a healthy and respectable upbringing. (Note once again the prevailing assumption that women were not capable of providing a respectable home on their own – possibly true to the extent that women’s wages then were significantly lower than men’s, even if they could find employment – and that men would inevitably be strong and reliable, and reliably employed, providers). To increase the chances of remarriage, long periods of mourning were discouraged. Not incidentally, when widows remarried their pensions usually fell away, to the relief of the State. Recognising that this loss of financial support would tend to discourage remarriage, the UK Government introduced a ‘marriage gratuity’, a lump sum representing one year’s pension, but then nothing more. This perhaps well-intentioned move had an unintended dark consequence: a widow in possession of such a lump sum was a tempting target for confidence tricksters, who would use any ruse they could (including marriage and then abandonment once the money had somehow been transferred to them) to separate the widow from her nest egg.

Remarrying was a risky step for other reasons, too. Neighbours could regard it as an act of disloyalty to the fallen husband, with social stigmatisation the result. (Soldiers too feared being thus replaced in their wife or sweetheart’s thoughts should they be killed.) And finally, of course, there was inevitably a great dearth of marriageable men.

Begging was sometimes the only recourse for a destitute widow

WIDOWS AS VICTIMS

Leaving aside that they had become ‘victims’ of bereavement, war widows could become victims in other ways too. We have noted how the working-class widow was likely to become the victim of officious and disapproving ‘Lady Visitors’ and of their later bureaucratic equivalents. If the husband was only listed as missing, the wife was not officially a widow and hence no pension was available (though the separation allowance would continue). If there were queries surrounding the soldier’s documentation (the marriage certificate for example) the pension might be considerably delayed.

We have mentioned the confidence tricksters who married the widow merely to get their hands on the ‘marriage gratuity’, but another potential trap awaited the younger widow, especially after the war. For she would be sexually experienced, and this made her all the more likely to receive eager proposals from men returning from war, which she, now without a man in her life, might too hastily accept. While such weddings no doubt led on to bliss, too many foundered on the realities underlying their origins.

Even a widow determined upon a life of respectable moderation and modest behaviour could not escape the widespread suspicions of married women who would frequently regard her as a sexual loose cannon capable of exerting a fascination upon husbands enmeshed in domestic tedium. Many would have to endure varying degrees of social exclusion, rumour mongering, and veiled innuendo until daily drudgery wore them down to grey anonymity. For similar reasons, the overseers of society, secular and religious, tended to regard widows with some caution as ‘sites of potential immorality’ and nodes of social disorder.

Post-war public commemorations could be traumatic for the bereaved. On the one hand they appreciated that their loved one’s sacrifice was remembered; on the other the depersonalised spectacle of pomp and ceremony, no matter how reverential the celebrations were (and sometimes there seemed to be more noise than remembrance), reopened psychological wounds that were only slowly healing. This reached its extreme, perhaps, in fascist Italy, where memories of the dead were appropriated to the glorification of the state, where painful loss was transmuted, by order, into willing and noble sacrifice. Similarly in Germany, the lamenting were gradually marginalised in favour of the ‘returned’ warriors and their maimed compatriots: these were the groups more in keeping with the ‘Aryan warrior’ image that 1930s Germany was keen to emphasise.

And widows – along with grieving sweethearts, siblings, and parents – were victims of their circumstances in one other, more insidious, respect, for “[r]ecent psychocardiological research [in 2012] has provided substantial evidence that mourning was and still is an important risk factor for morbidity.[5] You can, in other words, die of grief.

There is another, more direct way of dying from grief, of course: suicide. But how many women were unable to face the loss of a husband or sweetheart and took their own lives is not recorded. “Unbearable grief” was not a term recognised by English law: it was subsumed in the mildest verdict allowed – the insulting “while of unsound mind”. Then, to the stigma of “a suicide in the family” would often be added the refusal of the church to permit burial in consecrated ground, piling for the bereaved trauma upon trauma.

WIDOW’S PRIVILEGES

Few privileges arose from war-widowhood. Official platitudes, slowly diminishing neighbourly sympathy, and (failing a happy remarriage) meagre pensions hedged about with numerous restrictions were generally the widows’ lot. However, in Belgium, in 1919, war widows (along with bereaved mothers) received a rare benefit when, along with men and women who had served in the war, they were awarded the vote.

THE LARGER PICTURE

The ‘warfare state’ led inevitably to the growth of the ‘welfare state’ as countries were faced with the societal consequences of four years of total war. The systems developed to ensure total mobilization of state resources left an organisational imprint that could be adapted to peacetime use where state intervention on a hitherto unprecedented peacetime scale was required to avoid societal collapse or revolution. Huge numbers of demobilised soldiers, similarly large numbers of women who for the first, heady time had tasted financial and social independence, an army of disabled veterans dependent to some degree on institutional support, and the financial needs of the widows (and orphans) that we have discussed here demanded state involvement to a degree never seen before.

NOTES ON SOURCES

Principal sources for this article:

Other sources referenced:

Documents - telegram Source: https:// greatwar.nl/frames/default-feared.html

Pension card - Source: https:// www.westernfrontassociation.com/worldwar- i-articles/one-hell-of-a-row-a-war-widowspension

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A teenage browse along his father’s modest bookshelf that encountered a battered copy of Corbett-Smith’s 1917 book, “The Retreat from Mons”, seeded a life-long fascination with the Great War. A degree in Zoology, and a career in Marketing Research and PR notwithstanding, the fascination put down roots until retirement allowed it full reign, resulting now in a library of over 800 WWI volumes and a ‘book in progress’ on military observation balloons (and, as Journal readers will know, a small collection of verses dedicated to the war).

Brian, a ‘war baby’ (just), grew up in England and emigrated to South Africa in 1982. He now lives in Douglasdale with his long-time partner Annie.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org