The South African

The South African

Early years

He was born on 22 October 1847 on Doornfontein Farm, Winburg district of the Orange Free State, the son of Adrianus Johannes Gijsbertus de la Rey (died 1891) and Adriana Wilhelmina van Rooyen (died 1912). He was grandson of Pieter De la Rey, a school teacher who emigrated to South Africa from Utrecht, Netherlands in the early 1800’s. The family descended from French Huguenots who fled to the Netherlands during the religious persecution in the late 1500’s. The family settled in the Transgariep after the end of the Great Trek in the 1840’s.

De la Rey’s father was one of the Boer commandants at the Battle of Boomplaats in 1848. The Boer forces were defeated, and all participants in the rebellion had their farms confiscated by the British. The family trekked into the Transvaal and settled near Makwassie in the western Transvaal. De la Rey married Jacoba Elizabeth (Nonnie) Greeff on 24 October 1876. She was a daughter of Hendrik Adriaan Greeff (1828 -1883), the founder of Lichtenburg and first Commandant of the Lichtenburg district.

Jacoba Elizabeth “Nonnie” de la Rey, née Greeff

Portrait by Therese Schwartze 1902

Experience on commando

In 1876 he was elected Field Cornet and participated in the war against Sekhukhune. In 1880/1881 he was one of the besiegers of Potchefstroom during the First Anglo Boer war. In 1883 he became Commandant of the Lichtenburg district and fought in the war against Massouw of the Korana, and in the battle of Mamusa (Schweizer-Reneke) on 2/3 December 1885. In 1896 he was a member of the Boer commando that halted the Jameson Raiders outside Krugersdorp.

On the outbreak of the Anglo Boer War of 1899-1902 he was appointed as General Piet Cronjé's advisor by Commandant General Piet Joubert. At Kraaipan, on 12 October 1899 he led an attack on a British armored train on its way from Vryburg to Mafeking, the first shots of the war. He advised Cronjé not to besiege the town of Mafeking but his advice was ignored. Now appointed Veg- Generaal, he left for Kimberley and was involved at Kamferdammyn on 3 November.

At Belmont station the British shelled and charged the nearby hill which the Boers were occupying. The Boers fell back to Graspan/ Enslin and then to Tweeriviere/Modderrivier, to rejoin the larger force of Free-Staters and Transvalers under the command of Michiel Prinsloo and De la Rey. De la Rey instructed his men and Prinsloo's Free-Staters to dig in on the banks of the Modder and Riet Rivers. In the battle on 25 November, de la Rey was wounded in the arm by a shell splinter. His eldest son Adriaan was wounded and died of his wounds the following morning. At Magersfontein on 11 December his men were entrenched at the base of the hill, repulsing the attacking British.

He was then sent to the Colesberg front to counter Major General John French's advance. Involved at Agtertang, Keerom, Slingerfontein, Polfontein, Waterkloof and Arundel up until February 1900, he was reassigned to take command in the desperate action to stem the British advance on Bloemfontein and then Pretoria. This was after Cronjé surrendered on 27 February 1900 to Lord Roberts at Paardeberg.

During this next phase of the war he was active at Abrahamskraal and Driefontein outside Bloemfontein and then at Brandfort and Misgunstfontein drift during the British advance to Pretoria. He took a major part in the determined defence of Donkerhoek/Diamond Hill, east of Pretoria on 11-12 June 1900. With the reorganization of Boer forces for guerrilla action de la Rey became Assistant Commandant General for the western Transvaal. Sent to reorganize the area for the next two years he led a mobile campaign with a number of notable engagements of which the best- known are the attack on the Australians at Wysfontein, the siege of Elands River Post, Moedwil and Cyferfontein. He had a signal success at De Klipdrif/Tweebosch, near the modern town of Sannieshof, on 7 March 1902 with the capture of British Lieutenant-General Lord Paul Methuen.

Political career

De la Rey was elected a member of the Transvaal Volksraad in 1893 and served up to the end of the ZAR in 1902. The Boer republican government system did not allow for political parties. However, the population was factionalised in the three Dutch church groups and behind prominent leaders that contested the office of president. In the latter part of the 1800’s two factions emerged centered on the persons of Paul Kruger and Piet Joubert. The conservative Paul Kruger secured the support of most burgers and was elected president. The progressive Joubert, by default occupied the office of Vice President and Commandant General of the Boer forces. De la Rey and Louis Botha were supporters of the progressive faction under Joubert.

On 29 September 1899, in the sitting of the Volksraad just before the outbreak of war, De la Rey and Louis Botha spoke against waging war with Britain. Nevertheless, both did their duty to the bitter end after war was declared. De la Rey was involved with the peace negotiations at Vereeniging and was instrumental in convincing the diehard republicans to accept that the war was lost. He was one of the six Boer delegates to sign the peace treaty at Melrose House.

General J H “Koos” de la Rey,

Portrait by Therese Schwartze 1902

De la Rey shared in the vision of a united South Africa. He envisaged South Africa as an independent Republic in which his people, the Afrikaners, would experience freedom from domination. On 25 May 1904 de la Rey became one of the founding members and committee member of the ‘Het Volk’ political party with Botha and Smuts and in 1906 was elected to the colonial Transvaal parliament. He was a delegate to the national convention which led to the Union of South Africa in 1910. In collaboration with Botha, Smuts and Hertzog, he was a founding member of the South African Party and became a senator in the Union parliament.

In 1912 Hertzog had a fall out with Botha and Smuts and departed the S.A. Party to establish the National Party. This split in Afrikaner politics affected de la Rey intensely as he was very much set on preserving unity among the Afrikaner people. De la Rey and many of the old republican Boers did not feel at home in the system of political party representation. They grew up with the system of people’s representation which did not allow for political parties. On 26 August 1914 de la Rey’s loyalty to Botha and Smuts was tested severely. Invited by Tielman Roos, he spoke at the establishing congress of the National Party in Transvaal. (The National Party in the Free State had been established on 9 January 1914 under leadership of Hertzog.) In his speech he called for unity among Afrikaners and to the bitter disappointment of the attendees he did not support the establishment of this new political party. When the long-expected World War finally erupted in 1914, de la Rey opposed the Union’s participation in the war against Germany.

Siener van Rensburg

De la Rey saw in Nicolaas “Siener” van Rensburg a messenger from God. It is said that during the ABW (Anglo-Boer War) the visions from v Siener more than once saved de la Rey from defeat. From 1905 Van Rensburg started seeing visions about the coming World War. In a repeated vision he saw five bulls fighting. In time the number of bulls in the vision increased to fourteen. In the vision a blue bull stabbed a red bull in the side, spilling its innards. Van Rensburg interpreted the red bull to be Britain and the blue bull to be Germany. This vision of de la Rey’s old supernatural counsel from the ABW had a profound influence on him. He was convinced that the Germans would win the war and publicly stated that he preferred to live under British rule rather than German or Japanese rule. He stated his willingness to defend the Union against German aggression, but deemed it very risky to attack the Germans.

Louis Botha was convinced his old and trusted friend had taken leave of his senses when De la Rey tried to convince him of the certainty of the outcome of Van Rensburg’s vision. This reignited the the pursuit of independence amongst the conservative Afrikaner population, especially in the western Transvaal. None of them had any doubt that De la Rey would be the leader of a new movement towards independence.

De la Rey was under intense pressure at this time, torn between his loyalties towards Botha and other clean shaven friends amongst the progressive faction and his aversion to the horrors of war. In his love for his less sophisticated people, the bearded ones, he shared their unquestioning faith in God and did not wish to disappoint them. As well, he still yearned for Afrikaner independence.

The circumstances of his death - Background

After Serbian Gavrilo Princip assassinated the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo on 30 June 1914 war between Germany and Austria-Hungary, and Britain, France and Russia was under way by 4 August.

On 11 July 1914 Nicolaas van Rensburg told de la Rey of a vision he had had. He saw a white paper and a black one with fifteen (15) written on it hanging over Lichtenburg with blood dripping from it. Then he saw de la Rey, bare headed, and a black shroud hanging over Lichtenburg. Next, he saw an important South African visiting overseas, dressed neatly in a coat with gold buttons and a sword. When he returned to South Africa, the white paper with the number 15 again appeared. He again saw de la Rey, bare-headed. The man returning took off and discarded his fine garments and his sword. Then he saw a long wagon, steam-driven, coming from the north. There were only a few people on the wagon. De la Rey’s wife and children were on the wagon with an abundance of flowers. There was much food on the wagon, but nobody was eating. De la Rey was also present, bare-headed. The man that discarded the fine garments was also on the wagon. The wagon halted along the way, with many people assembled, grieving. In mid-July Van Rensburg again saw the vision of two bulls fighting. The blue bull was still victorious over the red bull. The effect of these visions, when they became known to the public, was a perception that Germany (the grey or blue bull) would defeat Britain (red bull). The perceived vulnerability of the British kindled a belief among many independently- minded Boers that the time was at hand to right the wrongs of the ABW. They were convinced that the restoration of the old independent Boer republic would be inaugurated at Lichtenburg on the 15th of an unknown month.

On 5 August, a call went out for the burgers to assemble on 15 August at Treurfontein (Coligny) in the western Transvaal. De la Rey was to be the main orator. Community members that supported Botha’s and Smuts’ reconciliatory policy between Afrikaner and English citizens raised the alarm in Pretoria. On 13 Aug 1914, de la Rey was summoned to Pretoria to meet with Botha and Smuts to explain his intentions. N.J. de Wet, Minister of Justice, and Schalk Burger (last acting president of the Z.A.R.), were also present. De la Rey explained that his intention was to calm the people and to prevent insurrection. Minister de Wet used the opportunity to warn De la Rey that he would use the law against him if his actions led to insurrection. De la Rey was much concerned by the threat levelled against him and it played a profound role in his decision not to stop at the police road-blocks the night he was killed.

De la Rey continues to call for unity

On 15 August de la Rey, accompanied by his old friend and fellow senator, Sammy Marks, met with 800 burgers at Treurfontein. In his speech he called on all to support Botha and the government. Many of the attendees, disappointed that the proceedings were not turning out as they had expected, left the gathering. On 26 August 1914 the National Party in Transvaal was established. De la Rey was invited to speak with the hope that he would support the new party. In his speech he again called for unity amongst Afrikaners and did not give his support to the new Transvaal National Party.

Christiaan de Wet unexpectedly visited de la Rey at his home on 3 September. He had already joined the National Party in the Free State. De la Rey asked De Wet to join him in prayer for guidance. De la Rey prayed to God to take his life if it was to be in the interest of his people. On 5 September de la Rey departed from Lichtenburg to attend the special sitting of Parliament in Cape Town. On his way he visited the military camp at Potchefstroom and delivered an address to troops of the De la Rey Rifles. He was Honorary General of this unit and asked of them to be loyal to their officers.

On 9 September, Parliament convened a special session to decide whether to declare war on Germany. The lower house made the decision to enter the war. The Senate met four days later in order to ratify this ruling. De la Rey spoke against joining the war but left the assembly before the vote was cast in order not to vote against Botha’s policies. The Senate approved the declaration of war and de la Rey left Cape Town by train, arriving at the Victoria Hotel in Johannesburg on 14 December.

Kemp and Beyers resign

On the previous day de la Rey’s former General, Jan Kemp, had tendered his resignation from the Union Defense Force and two days later Christiaan Beyers resigned as Commandant General of the Active Citizen Force of the U.D.F. On 15 September Beyers sent his car to fetch de la Rey so as to meet him in Pretoria. At about 19h00 Beyers and de la Rey departed Pretoria on their way to Johannesburg. To this day it is debated whether de la Rey was on his way to his farm at Lichtenburg or to Potchefstroom to meet with Kemp. It is also debated that, if he were on his way to Potchefstroom, whether his intentions were to join a Rebellion or to try to defuse it. They did not take the usual turnoff from Johannesburg to western Transvaal via Sauer Street. At that stage the Police was conducting roadblocks to apprehend the three Foster gang members, William Foster, John Maxim and Carl Mezar. They were accompanied by Peggy Korenico, Foster’s girlfriend. Foster had killed detective Mynott that afternoon. (The gang was cornered on 17 September in a cave on the East Rand and all committed suicide.)

Fatal Roadblock

De la Rey’s vehicle drove through three roadblocks without stopping. When they sped past the fourth roadblock, set up on the corner of Du Toit and De Wille Streets in Langlaagte at 21h16, Constable Charles Drury, a British veteran of the ABW, fired a shot at the tyres. The bullet ricoched into the vehicle and struck de la Rey in the back. He died in Beyers’ arms. He was 66 years old.

Motor car in which General de la Rey

was shot on the night of 15 Sept 1914

De la Rey’s eldest and only surviving son, Captain Hendrik de la Rey remained loyal to Botha and Smuts. He served as his father’s impromptu secretary and penned his memories of his father’s last days. These recollections were published by his son, Brigadier Jack de la Rey, SM, AFC, a pilot in the S.A.A.F., in Die Ware general Koos de la Rey. The booklet was compiled by Lappe Laubsher in 1998 and published by Protea Boekehuis. Laubsher is adamant that de la Rey was on his way to Lichtenburg. Beyers’s first statement also indicated Lichtenburg as their destination. Later, Beyers said they were on their way to the military camp in Potchefstroom to fetch de la Rey’s son and counsel Kemp for peace. From there they were going to Lichtenburg.

Since Hendrik was de la Rey’s only surviving son, it makes sense that he would not want him to serve in the coming war. Of de la Rey’s six children only two were still alive at this stage. His daughter Pollie was a devoted supporter of General Botha.

The funeral of Gen de la Rey 20 September 1914

A funeral service was held by Ds. H.S. Bosman in the main N.G. (Nederduitse Gereformeerde: Dutch Reformed) Church in Pretoria on 19 September 1914. After the service de la Rey’s body was transported to Lichtenburg by train, accompanied by Christiaan Beyers and the de la Rey family. Men of the old Krugersdorp commando who had fought under de la Rey stood guard at the coffin on the train. After his body had lain in state from 7h00 until 14h00 in the old NG church, he was buried on Sunday, 20 September with military honours at Lichtenburg main cemetery. About ten thousand people attended.

The cortège was led by the church warden, followed by three mounted burghers and ten burghers on foot who had fought under de la Rey. Then came the horse-drawn hearse, covered with flowers. Transvaal and O.F.S. flags draped the coffin, while the pall-bearers walked alongside the hearse followed by the family. Following them were representatives of the Governor-General, central government, provincial government, fellow Senators, other Members of Parliament and Provincial Councils, Mayors and Councillors of municipalities, ministers of the church and members of church councils. Next followed the funeral committee members, public officials and teachers, members of school boards and commissions, ex-officers, members of shooting clubs and the general public.

At the graveside speeches were delivered from a small platform by Louis Botha, Christiaan Beyers and Christiaan de Wet. After the speeches the coffin was slowly lowered into the grave. For some hours people showed their last respects, and the grave was finally covered.

General J.H.de la Rey’s grave in Lichtenburg

with its monumental headstone as restored in 2021.

See story which follows this one.

Conspiracy theories

Conspiracy theories started emerging. Some believed that the government wanted to assassinate Beyers, and de la Rey was hit because they changed seats midway to Johannesburg. A Judicial Commission of Enquiry was established under Judge Gregorowski and lasted from 22 to 29 September 1914. The commission focused on the police action but was also used to determine de la Rey’s and Beyers’s actions leading up to the tragedy. The following facts emerged and deepened the suspicions of government involvement in the tragedy:

A policemen had noted the registration number of Beyers’s car before they departed Pretoria. This officer also shone a light into the car when they passed him on their way. The departure time and possible estimated time of arrival in Johannesburg was thus known. It was determined that a barrier compelling motorists to stop at the first roadblock at Orange Grove, was altered to allow passage just before the vehicle in which de la Rey was travelling arrived at the post. The generals were thus not informed to be vigilant of police action to apprehend the Foster gang, like all those that arrived there before them were. Sub-Inspector EC Leech was blamed for not issuing the “don’t shoot” command to the post at Langlaagte. This was the only post he did not telephone with the order. He elected to drive there himself and only arrived after the incident. Leech committed suicide after the enquiry ended, deepening the suspicion of sinister involvement.

By the time the generals arrived in Johannesburg it was known that the Foster gang was on their way to the East Rand making the roadblocks on the generals’ path unnecessary for the original purpose. The enquiry did not prevent the rebellion, but some argued that de la Rey’s prayers were answered. His death had prevented a civil war. Had he lived to lead a rebellion the severity might have been much worse than it turned out to be.

This paper is based on a 2021 ZOOM lecture hosted by the Eastern Cape (SAMHSEC) branch of the Society.

The following appears on the inside back cover of Volume 19 No 3:

by Rev G Stephan Botha

In line with Victorian custom, General J.H. de la Rey’s grave was covered by an elaborate granite tombstone in 1917. A bronze bust by sculptor Fanie Eloff, grandson of President Paul Kruger, was affixed as centre-piece on the tombstone. For 104 years this grave was left undisturbed, although the collapse of municipality function in recent times has led to neglect of the graveyard. Visitors to the grave became few and far between.

During the weekend of 17/18 April 2021 it was discovered that the tombstone had been vandalised, and that the bronze bust had been stolen. A R20,000 reward was offered for the recovery of the bust which had not been found at the time of printing.

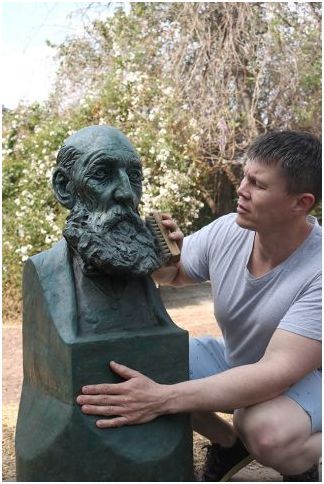

The F.A.K. (Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge) surveyed the damage and sponsored the restoration of the grave and monument. Jacques Muller, a sculptor from Pretoria, undertook to produce a replacement bust. He had previously made the replacement on the grave of President Paul Kruger. The replacement was made of a non-metallic material which has no economic value.

Photographs courtesy of Stephan Botha

The vandalised grave and damaged remnants.

The sculptor, Jacques Muller, with the replacement headstone.

A closer view of the restored headstone.

At the unveiling:Jacques Muller, the sculptor;

Dr Danie Langmer, Managing Director of the F.A.K.;

Mr Louis Pretorius, great-grandson of General H J de la Rey.

Mr Louis Pretorius with his mother,

Rosina Pretorius, granddaughter of

Gen H J de la Rey. Her mother, Pollie

de la Rey, was the general’s daughter.

This last photograph appears on the back cover of the issue:

Grave of General ‘Koos’ de la Rey in Lichtenburg, north-west province.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org