The South African

The South African

By Brig.-Gen McGill Alexander

Front cover photograph: Cover Illustration

SADF paratroopers jumping from a Lockheed Hercules C-130B of the SAAF in the early 1970s.

The insurgent war had not yet escalated and SAAF aircraft were not yet painted in camouflage

livery.

The South African Saviac parachute was not yet in production and paratroopers were still

using the US-designed and West-German produced T-10 canopy and harness.

The Southern Africa Thirty-Year War (approximately 1960 to 1990) included the counter-insurgency wars of the Portuguese in Angola and Mozambique (1961-1975), the Rhodesian “Bush War” (1966-1980) and the South African “Border War” (1966-1989). There is contention regarding the dates, with some historians commencing the conflict with the unrest in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1959 and others with the Mpondo Uprising in Transkei in 1960. There are others who include the internal unrest in South Africa during the early 1990s. But that there were about thirty years of armed conflict is certainly so.

The Thirty-Year War saw a significant number of airborne actions by the security forces, both by parachute and by helicopter. Consequently, there is occasionally conjecture amongst military buffs as to just where and when the South African Defence Force (SADF) carried out its first operational parachute drop.

The SADF only acquired a parachute capability in 1961, and during the Thirty- Year War the South African paratroopers executed several parachute operations. The biggest and most well-known was the raid on Cassinga in 1978. But it would be wrong to think that this was the only or the last parachute operation by the SADF. There were in fact more than 20 such operations, ranging in size from platoon to battalion strength, and they took place in Angola, Ovamboland, the Caprivi Strip, south-western Zambia, and Rhodesia. And this excludes the considerable number of special forces parachute operations and dozens of so-called “Fire Force” operations of various types that included parachute drops.

In this article, sourcing both declassified archival documents and interviews with participants, the events leading up to the first drop are described, as is the drop itself and the course of the operation that followed. Some of the lessons learnt from the airborne aspect of the operation and their consequences are then listed.

Paratroopers the world over are volunteers. Even those who are conscripted volunteer for parachute training. And as volunteers, they willingly place themselves in the vanguard of combat. It is therefore not surprising that almost every paratrooper hopes to carry out at least one operational parachute jump.

A Paratrooper from 1 Parachute Battalion

descending under a T-10 canopy,

with his personal kit suspended on

a nylon rope to hit the ground before

he lands.

The truth is, however, that only a small percentage of paratroopers ever do so, and even then, they rarely jump directly into combat. Britain’s Parachute Regiment, the famed “Red Devils” who earned such an enviable reputation in their parachute operations during the Second World War, have not jumped operationally since 1956. This, despite having been involved in low intensity operations during most of the time since then2. On the other hand, most of the paratroopers of Rhodesia participated in literally dozens of parachute operations, some of them doing two to three such jumps in one day³.

Paratroopers descending during a jump in the Caprivi.

Willem “Kaas” van der Waals, a former company commander at 1 Parachute Battalion, was the first known South African to participate in an operational drop since the Second World War. At the time, he was the South African Vice Consul in Luanda, responsible for liaison with the Portuguese forces in Angola. He jumped with the Portuguese paratroopers to the northeast of Luanda in 1972. Jumping from a twin-boom Nord Noratlas aircraft, he accompanied them as an observer and was dropped with them into the Dembos Forest. The area was dominated by the FNLA insurgents, and the paratroopers established a base in the forest, to limit the movement and freedom of action of the insurgents4.

Six more South Africans participated in a parachute operation in January 1974, this time with the Rhodesians. They were from the SADF’s 1 Reconnaissance Commando and joined the SAS in a cross-border airborne action into Mozambique as part of Operation Hurricane. In two low flying Dakota aircraft, they entered Mozambican air-space in the pre-dawn twilight. Under command of Commandant Jan Breytenbach, the South Africans were parachuted into Mozambique with about 35 Rhodesian SAS soldiers at daybreak.

This was the first operational jump ever by members of a South African airborne unit. They operated in Mozambique for five weeks, were involved in numerous contacts with both ZANLA and Frelimo insurgents and there were casualties on both sides, though none among the South Africans5.

But these were not South African parachute operations. Barely four months after the Rhodesian operation, the South Africans would get their chance.

The early 1970s saw an intensification of the insurgent war on the northern border of what was then South West Africa. Protection of the borders at that stage was still the responsibility of the police and the SADF was little more than a small, low profile presence in the area. In April 1973, after a spate of successful SWAPO ambushes and mine incidents in the Caprivi, the SAP relinquished responsibility for border protection to the SADF. The SADF officially took over this responsibility at the end of June 1973.6

The revolution in Portugal and the chaos that ensued in Angola saw a further increase in the SWAPO insurgency, particularly in the Caprivi Strip.7 The Portuguese were reluctant to act against any of the insurgent groups in Angola and this gave SWAPO unprecedented freedom to cross Angolan territory with impunity.

At the time, the SA Army’s 1 Parachute Battalion consisted of a nucleus of highly-trained Permanent Force officers and NCOs, but the soldiers and some junior leader group were all conscripts who had volunteered for training as paratroopers. National Service, as it was called, consisted of one year of full-time training and operational deployment. This was followed by annual refresher camps, for which the trained paratroopers would be transferred to 2 Parachute Battalion, a Citizen Force unit established in 1971.8 There would be several “intakes” of National Servicemen every year, and each intake would provide volunteers for a different company of 1 Parachute Battalion. The companies were therefore at different stages of their training at any given time, so the battalion could not be deployed as a battalion.9

By May 1974, 1 Parachute Battalion had only one under-strength company (B- Company) fully trained and available for operational deployment. A second company (D-Company) was nearing the end of its training and would soon be available for deployment. A third (A-Company) still had several months of training to do, while the fourth company (C-Company) had only recently commenced its training. D-Company was scheduled to arrive in the Eastern Caprivi Strip on 4 June 1974 to complete its counter-insurgency training before being deployed, and would be based at Katima Mulilo.

Brigadier Constand Viljoen, the Army’s Director of Operations at the time, had directed the arrival of D-Company, 1 Para- chute Battalion, for its scheduled deployment to be effected by parachute. This was for a show of force close to the Angolan and Zambian borders and he instructed that the company be dropped immediately east of the Kongola Bridge. The drop would involve 140 troops and 2,000kg of equipment. After the jump, the company would first have to complete its counter-insurgency training in the Caprivi before it would be able to actually deploy.10 This was by then a common practice by 1 Parachute Battalion, providing counter-insurgency training in the same terrain where the soldiers would subsequently operate.

The date for the drop was 5 June 1974. It was planned as a big public relations exercise to ensure that the local population was made fully aware of the military might of the SADF and of the ability to project force over long distances at speed. Chiefs and headmen of the Eastern Caprivi were invited to watch the demonstration and the Portuguese were notified of the intention to carry it out so that they would not become alarmed when it happened.11

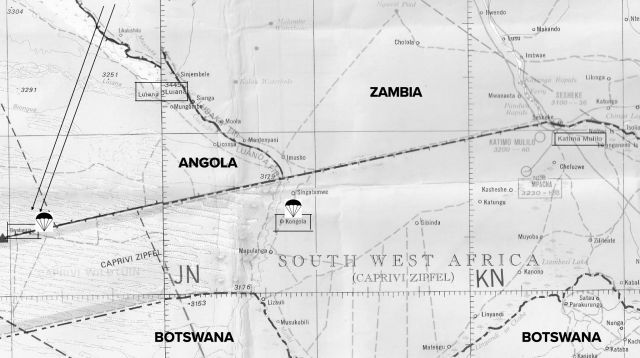

Map showing approach route of insurgents and

locations of parachute drops in the Caprivi Strip

It was at this stage that the unexpected occurred. On 30 May 1974 reports were received from Portuguese sources that a large group of SWAPO insurgents was moving from Zambia, having entered Angola north of Luiana to cross the south-eastern corner of Angola, moving towards Bwabwata. Their destination appeared to ultimately be Ovamboland, the most populated part of South West Africa. These reports were confirmed by other sources.

What alarmed the South African military authorities was that the main force was reported to consist of some 200 insurgents. This was a far bigger infiltration than had ever been attempted before. Some reports indicated that they intended to attack Bwabwata, where a very small SADF element was stationed. Bwabwata was right on the Angolan border, isolated and far from any reinforcements. It was located approximately halfway along the Caprivi Strip, about 18km north of the so-called “Golden Highway” – a road not yet tarred, passing through deep, often impassable drifts of sand. It would be almost impossible to reach the little garrison overland at Bwabwata in time with a force large enough to counter 200 aggressive insurgents.12 With only a company of infantry deployed by the SADF over 150km away in the somewhat distant Western Caprivi, the insurgents posed a very real threat. There was only one Alouette III helicopter in the entire Caprivi and reinforcements could not be moved over the intervening difficult and sandy terrain in time.

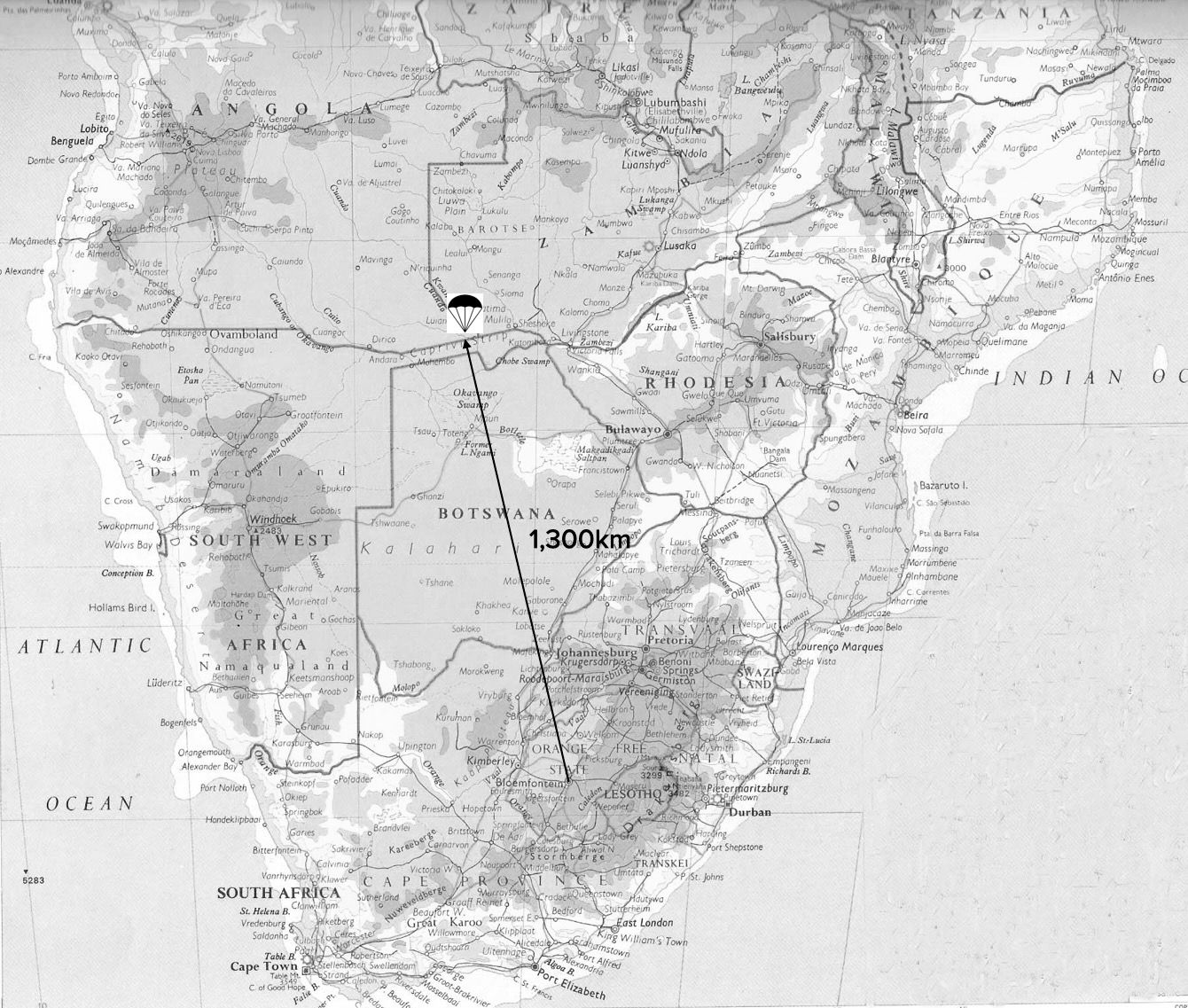

Brigadier Viljoen realised that the only viable option was a parachute drop. But the paratroopers were in Bloemfontein, 1300km away, as the crow flies. D-Company was not yet trained in counter-insurgency and the only fully trained company, B-Company, was under strength, consisting of only two platoons. On the early morning of 4 June, Viljoen signalled 1 Parachute Battalion to reinforce B-Company and carry out a drop that same night at Bwabwata to counter an insurgent attack. The company, busy with field training, was rushed back to the base in Tempe, drew ammunition and parachutes and prepared their equipment. The battalion commander, Commandant Hans Möller, briefed the company commander, Major Joe Verster, and reinforced him with an additional platoon. It was made up of whichever paratroopers could be scraped together, under command of the battalion’s transport officer, Captain James Hills.13 By nightfall B-Company was fitting parachutes and boarded the two C-130B Hercules aircraft that had been sent from Pretoria to fetch them.14

Major Jan “Jumbo” Human of 1 Parachute Battalion was in the Caprivi at the time, at Katima Mulilo. He had recently arrived to be the Dropping Zone Safety Officer (DZSO) for the show-of-force jump due to take place the next day. Human, a qualified tactical free-fall paratrooper, was now flown to Bwabata by the only helicopter in the Caprivi, to take charge of the DZ for the operational drop.15

The heavily-laden paratroopers, after flying for over two hours, jumped at 20h50 that night16. It was the first operational parachute deployment by South Africa.17 Coincidently, it was just about 30 hours short of the 30th anniversary of the start of the historic airborne landings of the night 5/6 June 1944, that preceded the D-Day amphibious landings of operation Overlord. In fact, at the very time the South African paratroopers were jumping, veterans of the Overlord drop were gathering in Normandy to celebrate their anniversary.18

The South African paratroopers suffered only one serious injury during their night drop right on the borderline between Angola and the Caprivi Strip. One man fractured his back during the jump and had to be evacuated by the helicopter. The remainder immediately moved into Angola in the darkness, and set up ambushes along the likely insurgent approach routes.19

Early the next day, D-Company, under command of Major Dick McIntosh took off from Bloemfontein in three C-130s. Viljoen had made it clear that should the operational situation escalate, he was prepared to re-route the company to jump at Bwabwata to reinforce the company that had jumped the night before, despite their incomplete training. 20 They therefore took off knowing their jump might be an operational one. The battalion commander accompanied them.

Map showing distance flown

after take-off in Bloemfontein

However, it was not necessary to divert them and at 10h00 they carried out the show-of-force parachute descent, as scheduled. The additional 2,000kg of equipment that was dropped with the 140-man company included several folding “Tico Cars”.21 This was the name given to the AS-24 motorised tricycle vehicles manufactured for airborne forces by Fabrique Nationale in Belgium. The Belgian paratroopers had used them during their 1964 battalion-sized combat drop on what was then Stanleyville, in the former Belgian Congo (Operation Red Dragon).22

Major Human had been flown back to Mpacha airfield near Katima Mulilo that morning. He and two other pathfinders preceded the main landing by 30 minutes by carrying out a free-fall jump from a Cessna 185 light aircraft. They laid out the DZ markers in time and controlled the drop.23

Only some 40km away, while the local people were being impressed by this show of force, the paratroopers of B-Company were patrolling and laying ambushes, awaiting the arrival of the largest group of SWAPO insurgents yet to attempt to enter South West Africa.

But the insurgents appeared to have got the message and dispersed into smaller groups, avoiding the Bwabwata area. Two four-man teams of special forces from 1 Reconnaissance Commando, under Commandant Jan Breytenbach, were deployed to locate them inside Angola.24 The terrain was thickly forested with swamps in places, so it was easy for small groups of guerrillas to vanish in the vast, trackless area.

After four days, the ambushes were lifted and Bedford trucks, sandbagged for protection against mines, were sent through from Katima Mulilo. This was before the later renowned mine-protected vehicles had been produced by South Africa. The paratroopers used them to penetrate deeper into Angola, helping the special forces hunt for the insurgents. Additional troops were systematically brought into the Caprivi and the intensity of the counter-insurgency operation reached an unprecedented height. By then the dispersed insurgents appeared to have aborted their plan to penetrate all the way to Ovamboland and it seemed they were attempting to return to Zambia. The special forces and paratroopers searched for tracks and temporary bases, reconnoitred possible crossing places over the Luiana River and laid more ambushes. After more than two weeks of hunting through the bush, the hunters finally caught up with the hunted and made contact.25

On 23 June 1974, there were three contacts in an area approximately 100km north of Mucusso. In the first, the special forces surprised a group of ten SWAPO insurgents at a waterhole, killed two and wounded a third. Later in the day the paratroopers shot an armed insurgent dead, and in the early evening the special forces came up against a group of 30 insurgents. In the furious fire fight that followed, several insurgents were wounded and one South African was killed. Lieutenant Freddie Zeelie was the first SADF soldier to die in the Bush War.

Lt Freddie Zeelie, a Special Forces soldier,

who was the first SADF member

to be killed during the Border War

The insurgents withdrew towards Babangando, and in small groups they crossed the Luiana and then the Cuando Rivers, retreating back into Zambia. By the end of June all the SADF troops had been withdrawn from Angola. From documents found on one of the insurgents who had been killed (and who was apparently a leader), it appeared that the group that had attempted to infiltrate was in fact only about 50-strong – there had not been 200 of them as had been reported by Portuguese intelligence.26

Nevertheless, the size of the group of insurgents was alarming, signalling a definite escalation of the war.

Paratroopers from A Company, 1 Parachute battalion, crossing the Babangando Drift of the Luiana River while patrolling in SE Angola in October of 1974. They carried out area operations for some months after the initial parachute insertion.

Brigadier Viljoen ensured that the SADF presence in the Caprivi was substantially increased. There were also more show-offorce jumps by paratrooper companies.27 Viljoen instructed that one platoon of paratroopers from 1 Parachute Battalion was now to be permanently stationed at Rundu with a Dakota aircraft and several Puma helicopters. This platoon, relieved on a rotational basis, would provide the operational military headquarters located at Rundu with an airborne reserve.28 He also insisted that suitable dropping zones be identified close to every base in the Caprivi so that parachute reinforcements could be dropped if necessary. A stock of sufficient parachutes was maintained at Rundu to enable several jumps to be carried out.29

This arrangement was the precursor to what became the South African version of Fire Force, so effectively developed by the Rhodesians. It was to prove the tactical framework for the airborne employment of the South African paratroopers during much of the war that would steadily escalate over the following fifteen years. Unfortunately, it would also detract from strategic thinking regarding their employment potential.

The first operational parachute drop by the SADF did not have a specific code-name – it was merely a part of the larger Operation Focus that had been running since February 1972. Yet it warrants consideration in any study of SA airborne operations, because the largest attempted infiltration of an insurgent group until then was effectively thwarted. The rapid deployment of the paratroops had forced the insurgents to disperse and the dogged pursuit for 18 days by the paratroopers and the special forces, culminating in a day of skirmishes, had compelled them to abandon their mission and to withdraw back to the safety of Zambia. Although it was an effective example of the tactical versatility of an airborne force, the operation held the seeds of a strategic action. It provided a clear illustration of the strategic potential of an airborne force to be moved at short notice over thousands of kilometres to an otherwise immediately inaccessible area of crisis.

Yet, it also revealed glaring shortcomings:

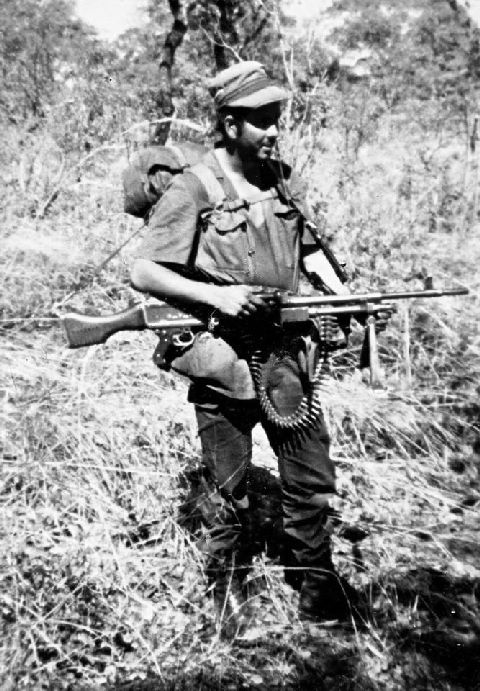

A paratrooper light machine-gunner,

his bush hat folded to form a cap so that the brim would not affect his hearing,

moves from the DZ to participate in the

laying of an ambush.

Until these five issues were confronted, no airborne force could be considered strategic. Most of them were addressed in the years that followed, especially once a parachute brigade had been established. However, the divide between tactical and strategic thinking when determining the role of the paratroopers remained a contentious issue, with most of the younger paratroopers quite satisfied with being relegated to a tactical role in support of ground forces. Few of the more senior officers understood the value, nor did they appreciate the capability of, a self-sufficient airborne force. That airborne operations are frequently high-risk undertakings cannot be denied. However, there are, in so- called “small wars of low intensity”, ways in which the risks can be substantially reduced, provided that commanders and their staffs are properly trained in the capabilities and limitations of airborne forces.

Fortunately, that first parachute operation, little-known and small as it was, had a profound effect on the thinking of those involved in airborne forces. A process of building up the airborne capability was embarked on by the SADF. When Con- stand Viljoen became the Chief of the South African Army, he initiated the establishment of 44 Parachute Brigade.30 Thereafter, the South African Air Force transport squadrons exercised in the tactical execution of mass operational drops of men, vehicles, and other heavy equipment.31 The SAAF became proficient in three sophisticated and advanced air-supply systems, secretly acquired through Israel: the Container Delivery System (CDS), the Platform Load Extraction Delivery System (PLEDS) and the Low Altitude Platform Extraction System (LAPES).32

In cooperation with the SAAF and using secretly recruited American instructors, the capability was developed to carry out High Altitude Parachute Operations (HAPO), using oxygen breathing apparatus. This included both High-Altitude Low Opening (HALO) and later also High- Altitude High Opening (HAHO) parachuting.33 A pathfinder sub-unit was established, and selected paratroopers were given specialised training for this role.34 The SA Army expanded its airborne capacity from only infantry to include units of light artillery, light armoured cars, anti-aircraft, maintenance, combat engineers, and technical specialists. All of these could be parachuted, and the combat units could be dropped with their main armament and light vehicles as well as other equipment.35

The parachute brigade headquarters formulated a detailed airborne doctrine and integrated its procedures to accommodate all arms. The joint planning ability of the headquarters matured to the level that enabled effective command and control of a balanced airborne force of battalion group and larger to be carried out, including the employment of a specially equipped airborne command post.36

SADF paratroopers jumping from a Lockheed Hercules C130B

of the SAAF in the early 1970s

Accurate intelligence for airborne operations, however, remained problematic. Although many such operations (both parachute and helicopter) were carried out, an inordinate number were plagued by poor and inaccurate intelligence. 37 The parachute brigade was never afforded a permanent, specialised intelligence capability and many airborne actions were conducted under the operational command of non-airborne headquarters.

Nevertheless, by the time the Thirty-Year War ended around 1990, the SADF fielded the most potent airborne force in Africa and one of the most balanced and advanced airborne formations of any comparable country in the world. While it is true that those airborne operations that were executed after 1974 remained predominantly infantry actions, the SADF was able to viably plan and rehearse for some impressive strategic contingencies.38 These required precisely the balanced airborne capability that had been built up.

For the paratroopers of South Africa, it was the high point of their development.

Sources:

SANDF Documentation Centre Archives:

Chief of the Army Group

Chief of the Army Director Operations Group

General Officer Commanding Joint

Combat Forces Group

Chief of Defence Staff (Kommandant Generaal) DGAA (1) Group

Oorlogsdagboeke Group

1 Military Area Group

1 Para Bn Group

Reports Group

Other Archival Sources:

Defence Amendment Act No. 85 of

1967.

Operational Diary of A Company, 1 Parachute Battalion, 22 August – 25 October 1974.

44 Parachute Brigade Information Brochure, 1991.

Troll, Capt P.: “History of 44 Pathfinder Company”, mimeographed information sheet, dated October

1989, 44 Para Bde.

44 Para Bde “Bevelswaarderinig, OefYsterarend III”, 44 VALSK BDE/ 308/1/1/YSTERAREND III,

19 February 1988.

Operational Diary of E-Coy, 1 Para Bn (July 1978 Intake)

Operational Report, D Coy 1 Para Bn, 28 December 1978 – 29 April 1979, 2 Military Area.

Interviews:

Maj Gen J.P.M. Möller

Brig W.S. “Kaas” van der Waal

Col J.R. Hills

Cmdt E.P.K. Ferreira

Correspondence:

E-mail letter from Col J.H. “Blikkies” Blignaut (Ret) in Pretoria, dated 12 February 2014. He was the course leader during the first HALO course in 1977.

Published Works:

Adams, Mark & Chris Cocks: The Rhodesian Light infantry, Africa’s Commandos, Helion & Co, Solihull, 2013.

Crookenden, Lt Gen Sir Napier: Dropzone Normandy, Ian Allen Ltd, Shepperton, 1976.

Kershaw , Lt Col Robert:Sky Men, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 2010.

Leys , C. and J.S. Saul (eds): Namibia’s Liberation Struggle: The Two-Edged Sword, James Currey, London, 1995.

Odom , Maj Thomas P.: Dragon Operations: Hostage Rescues in the Congo, 1964-1965, Combat Studies Institute, US Army Command & General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, 1988.

Pittaway , J. (ed.): Special Air Service Rhodesia: The Men Speak, Dandy Agencies, Durban, 2010.

Spies , Prof F.J du T.: Operasie Savannah, Angola, 1975–1976, SADF, Pretoria, 1989.

Van der Waag , Lt Col (Prof) I.: A Military History of Modern South Africa, Jonathan Ball, Johannesburg and Cape Town, 2015.

Journals/Periodicals:

Assegai, April 1977.

Ad Astra, 14, 5, May 1993.

Newspapers:

Eastern Province Herald, June 1974.

Photograph Albums:

Alexander, M: Photograph Album, SADF 5 (44 Para Bde 1987).

Notes

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org