The South African

The South African

By Robert Davidson

Background:

The siege of Ladysmith began on 2nd November 1899. Gen Sir Redvers Buller’s Natal Field Force tried unsuccessfully to break through to Ladysmith at Colenso on 15th December 1899. Hoping to outflank the Boers, Buller’s army next marched westwards to the upper Tugela River. On 16th January Gen Lyttleton’s 4th Brigade crossed the Tugela at Potgieter’s Drift, but Buller found the Boer position: “too strong to be taken by direct attack” (Maurice, 1906, p625).

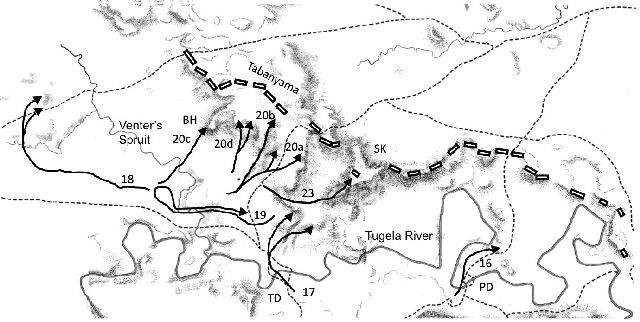

Gen Louis Botha reported to President Kruger that “positions were even better than those at Colenso and that, if Buller would attack, he could not possibly succeed in his attempt” (Kemp, 1941, p273). Buller thus remained where he was, while his deputy, Lt Gen Sir Charles Warren, took the larger part of the force further upstream. Warren’s orders were to break though in the west, march east, and trap the Boers opposing Buller (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. British troop movements on the upper Tugela, 16-26 January 1900.

TD = Trichardt’s Drift; PD = Potgieter’s Drift; SK = Spion Kop; BH = Bastion Hill.

16: 16th Jan. Gen Lyttleton’s 4th Brigade crosses the Tugela.

17: 17th -18th Jan. Gen Warren’s 5th Division crosses the Tugela.

18: 18th Jan. Lord Dundonald’s Mounted Brigade ambushes Boers near Acton Homes.

19: 19th Jan. Gen Warren’s 5th Division fails to march west.

20a: 20th Jan. Gen Woodgate’s brigade takes Three Tree Hill and Picquet Hill.

20b: 20th Jan. Gen Hart’s brigade advances onto Tabanyama.

20c: 20th Jan. SALH takes Bastion Hill.

20d: 20th Jan. Gen Hildyard’s brigade occupies part of Tabanyama.

23: 23rd Jan. part of Gen Woodgate’s brigade takes Spion Kop.

Crossing Trichardt’s Drift

Warren’s 5th and 11th Brigades crossed the Tugela at Trichardt’s Drift throughout 17th and 18th January. On 18th January, Lord Dundonald’s Mounted Brigade won a minor victory near Acton Homes by ambushing a Commando. The 19th January was wasted in a futile attempt by the infantry and transport to reach Dundonald (Davidson, 2020, p213) (Fig. 2). On the 19th January Warren instructed Dundonald: “I want you close to me” (Dundonald, 1926, P187), and made plans to capture the irregular plateau west of Spion Kop called Rangeworthy or Tabanyama (from isiZulu “intabamnyama”, meaning “black hill”). Warren’s assault would start in the east and move westwards.

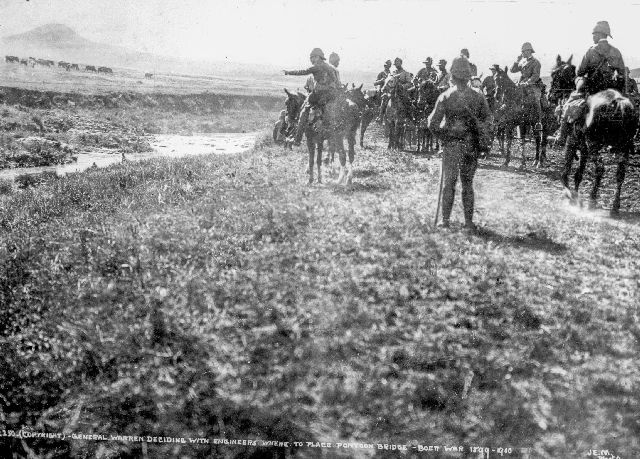

Fig. 2. Gen. Warren and Royal Engineers discuss

crossing Venter’s Spruit, afternoon of 18 January, 1900.

Bastion Hill is on the skyline.

Western Cape Archives J1191.

Taking Tabanyama

At dawn on 20th January, the 1st South Lancashires and the 2nd Royal Lancasters of Gen Woodgate’s 11th Brigade took Three Tree Hill and Picquet Hill. They were baffled to find they were unopposed. Three Tree Hill became the main Royal Field Artillery (RFA) position, where thirty-six 15 pounder field guns of the 7th, 19th, 28th, 63rd and 73rd Batteries quickly brought the Tabanyama plateau under shrapnel bombardment; their range was up to 3,750m (Fig.3).

Fig.3. A 15 pounder field gun of Maj Henshaw’s 7th Battery RFA firing on the

Fairview-Rosalie road, just east of Three Tree Hill, 20th January 1900. Green Hill and

Conical Hill are on the skyline at right of picture.

Black & White Budget, London, 17th March 1900, p12.

The Boers melted back to their prepared trenches on the “true” crest of Tabanyama. They and their agterryers had worked incessantly on these trenches, which ran, in short sections, for about 6 km from Green Hill in the east, along the ridge of Langkop, to Platkop in the west (Figs.1, 4).

Fig. 4. Making a Boer trench on Tabanyama, January 1900. Boers and their

agterryers are using steel bars to move rocks into place.

Free State Archives VAB 1535.

These trenches provided around 1,800 burghers a superb field of fire. Botha’s strategy here, as at Colenso, lay in drawing the British within Mauser rifle range, i.e. within 2,000m. From their trenches, each burgher could fire 10 to 15 aimed shots a minute; they also had a few machine guns. The 168-grain, high velocity, smokeless, steel-jacketed 7mm Mauser ammunition had a flat trajectory and was lethal at very long ranges. As evidence of this, Lt Col Dick-Cunnyngham VC had been killed in Ladysmith by a Mauser bullet fired from 3.5 km away. Botha enticed the British to take the southern crest: “for the enemy to try to charge over those thousand yards means suicide, because the open ground they had to move on could be covered by crossfire ... our officers knew damn well what they were doing when they chose the positions” (Kemp, 1941, p278). The fighting trenches concealed and protected the burghers. About 500m further back, cut into the steep reverse slopes of Tabanyama, they also built shelter trenches - invisible and safely below the trajectory of shrapnel and bullets (Fig. 5).

Woodgate’s two other battalions (2nd Lancashire Fusiliers and 1st York & Lancasters) advanced north from Fairview Farm, separated from Three Tree Hill by a deep ravine, nowadays called Battle Spruit. As they appeared on the plateau they immediately came under Mauser fire.

The West Yorks: “... we were told to advance though there were only 1,000 yards from the position & onto an absolutely open plain with no cover... before we have [sic] gone 300 yards most of us were shot down...” (Kearsey, 1900). “All day long we worked and fought under a hot shell and rifle fire without food or water, only too thankful when we were actively fighting, and so could forget to some extent hunger and thirst, the heat of the rocks below, and the blazing sun above” (Kearsey, 1903, p14).

The Lancashire Fusiliers: “Before long... an uncontrollable tendency asserted itself to collect in pockets of the ground for shelter, for breathing space, and for the summoning of resolution for further advance. On the first few occasions the halt was momentary, but the impulse to linger ever grew until finally, as the sense of physical danger overpowered the mental resolve, and as the hills loomed more threateningly ahead, the laggard progress stopped for good and all, and the tired and dispirited attackers longed only for dark” (Charlton, 1931, p104).

Fig. 5. Boers and their agterryers posing outside their shelter on the reverse slope of

Tabanyama, Jan 1900. The sandbags on the roof protect against stray bullets and

shrapnel. The burghers carry 7mm Mauser and 8mm Guedes rifles.

Wellcome collection.

Gen. Hart led his Irish Brigade (1st Borders, 1st Inniskilling Fusiliers, and 2nd Dublin Fusiliers) through the sheltering men. Pte Phipps of the Borders: “As soon as we started to advance the bullets began to fly, but we took no notice of this; when, imagine our surprise to see our firing line cuddled up in a heap behind the small hill ... (approx. GPS -28.64318, 29.47669). When we got to them we could plainly see they were in a state of blue funk, the officers were as bad or worse than the men. Our men indignantly told them what they thought about their action, & after a lot of persuasion (one way or another) they commenced to advance like a pack of frightened sheep. All of a sudden an automatic Maxim Nordenfeldt (pompom) began to play upon us. That stopped the firing line, for flat on their faces they fell & devil of a move would they make at all. Then the effects of discipline was exhibited. Our officers, equal to any emergency, shouted, 'advance & leave the cowards there', and to a man the Dubs & Borders responded, walking along like men on parade” (Carver, 1999, p74). “Immediately they showed their heads they were caught by a hailstorm of bullets, and seven men dropped ... in short energetic rushes, they had managed to get within 900 yards of the enemy.” (Creswicke, 1900, p103). Coming under fire, the Borders and Dublins swerved right, sheltering in a Y-shaped ravine at the head of Battle Spruit (GPS approx. 28.63285, 29.48428), only 800m below the Boers on Langkop.

Around 3pm the men were ready to storm the trenches, but some units were now so far ahead of the British line they might be cut off by “a commando of 500 Boers on their left” (Burleigh, 1900, p317). In fact, there was no such commando. After Bastion Hill was lost (described below), Kommandant Christaan Fourie’s Middelburgers on Platkop had fallen back under barrage from Three Tree Hill, leaving a gap on the Boer western flank. The firing from Platkop came, not from a commando, but from just three burgers: Henri Slegtkamp, Oliver “Jack” Hindon and Jan de Roos. They were scouts of Edwards’ Verkennerkorps who had reoccupied the abandoned position at Platkop. They unfurled a large “Vyfkleur” flag, which Hindon’s girlfriend had sewn. It was the ZAR “Vierkleur”, with a diagonal orange stripe added for the OVS (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Henri Slegtkamp, the Boer hero of Platkop, with his Vyfkleur flag.

This is one of a series of photographs taken soon after the battle, in which

they re-enacted their heroism. This was Slegtkamp’s personal

copy of the photo.

Courtesy of Henk Loots.

Among the rocks of the Platkop position they suspended the flag on a discarded rifle, to indicate a Commando headquarters. The three burgers crept forward to reconnoitre the ravine south of Platkop. Seeing no soldiers approaching, they returned to Platkop, moving about and firing furiously, to give the impression of a large force (Preller, 1942, p82). The ruse worked: “Hart ... was on the point of ordering [his men] to close and sweep the enemy from the hill when a peremptory message arrived from General Clery to stop all further advance” (Inniskilling, 1928, p419). The RFA turned their attention to Platkop, and this allowed Maj Wolmarans of the Staatsartillerie to position a pom-pom behind Langkop. “When the ... pom-pom started pumping, the brave three returned intact to their commando. If then the enemy knew how unprotected and poorly defended that koppie was, they would surely have charged and taken it; and if they did, then our right flank would have been in a bad position, and the enemy could have taken the road, exposed us to a heavy flank attack, taken Tabanyama, and trapped us on Spioenkop” (Kemp, 1941, p278-279; Blake Knox, 1902, p50). The three Boer heroes survived the bombardment, to be congratulated by Louis Botha: “Fluksgedaan, jongens!” (Penning, 1901, p 479).

Taking Bastion Hill

Bastion Hill is a distinctive landmark, named after its resemblance to an Anglo- Saxon earthwork. It extends 1000m south from Tabanyama, its flat top 200m above the Tugela plain, and its steep slopes able to shelter anyone climbing it. At 5.20 a.m. Warren had messaged Dundonald (in triplicate, to prevent misunderstandings): “You must take care that you are not cut off, and must keep touch with the main force” (Dundonald, 1926, p189). Leaving the Composite Regiment near Acton Homes, the 500 remaining mounted men returned to their camp 3km south of Bastion Hill, unobserved by the Boers. Dundonald was told: “Go a little way up it. See what sort of place it is and who is there. If it is strongly held, come back; but if it is not, go on, take it, and hold it" (Atkins, 1900, p229).

“A” Squadron of the South African Light Horse under Col Byng and Maj Childe led the assault. As they rode north from the Mounted Brigade camp they were initially concealed by the banks of Venter’s Spruit and an acacia forest (it has since disappeared). As the SALH troopers left the forest, the two Boer 75mm Creusot guns under Lt von Wichmann began to shell them accurately (Churchill, 1900, p320). The troopers galloped forward and dismounted in a donga leading to the foot of Bastion Hill.

Fig. 7. Lt Winston Churchill, SALH, who brought up the machine guns near Bastion Hill, 20th January.

Lt Winston Churchill (Fig. 7) brought up the Mounted Brigade’s .303 calibre machine guns: the 13th Hussars' Maxim under Lt Clutterbuck, one of Dundonald's “galloping” Colts under Capt Hill, MP, and the SALH Maxim, under Maj Villiers. These were set up on the bank of a donga (approx. GPS -28.63934, 29.44839) and opened fire on the Tabanyama sky-line at 2,000m. “Their noise attracted the attention of the Boer gunners to the westward, and shell after shell from the enemy dropped with remarkable accuracy into the wood... another shell fell within a yard of the leader, a moving target at 7,000 yards showing the accuracy of the enemy's fire” (Churchill, 1900, p322).

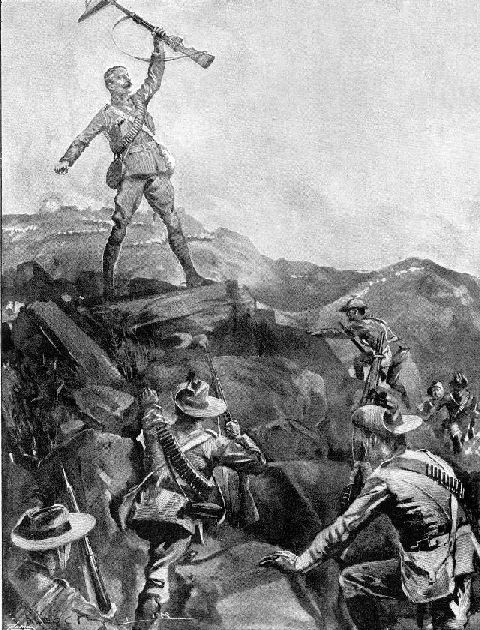

The dismounted SALH “drew open like a fan into their line of advance” (Atkins, 1900, p229) and scrambled up the steep slope of Bastion Hill, out of sight of the Boers. Trooper Tobin led: “Up he went hand over hand, up an ascent like the slope of a bell-tent. Everyone who watched held his breath for a man to fall - not from the steepness, but from a bullet. Ten minutes before all the others he reached the top...” (Atkins, 1900, p230). “The crest of the hill was first reached by Capt. Shepherd's squadron of the S.A.L.H... the top edge of it was swept with bullets from the Colts and supporting squadrons” (Dundonald, 1926, p187). At 2:50pm Tobin waved his sakabula-plumed hat upon his rifle, to signal the machine-guns in the wood below to divert their fire from the summit (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Tpr Tobin of the SALH takes

Bastion Hill; 2:50pm, 20th January 1900.

Painting by A Ball, 1900

With the Flag to Pretoria Vol 1 p273,

London: Harmsworth.

“No Boer was there, and the hill in a few minutes was ours”. “It was splendid to watch,” Lord Tullibardine said the next day: “It was a V.C. thing, and yet, if you know what I mean, it wasn't” (Atkins, 1900, p230). Tobin was erroneously reported to have been killed by a shell the next day; he was awarded the DCM.

On the flat top of Bastion Hill the SALH came under fire from the entrenched Boers on Platkop, 1.5km away and 30m higher. The SALH were unable to advance on the plateau. A signaler, L/Cpl Coghlan, was wounded, and there were eight bullet holes through the flag of another signaler (Dundonald, 1926, p191). Thorneycroft's Mounted Infantry and the 13th Hussars arrived to occupy the slopes, keeping below the crest.

Later that afternoon, Maj Childe was sitting on the summit, partly sheltered by rocks, when a Boer shell struck. Dundonald had been with Childe, and had left him for a few minutes to explore the summit. On his return, Dundonald found Childe dead and blood pouring from “a fearful wound in his head”(Dundonald, 1926, p190). Six others nearby were wounded. Childe was carried under heavy fire to the bottom of Bastion Hill by Maj Hinde, R.A.M.C and stretcher-bearers of the Queen's (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Ambulances lined up with Bastion Hill in the background.

Rangeworthy Military Cemetery is on this site today.

Black & White Budget, London, 17 March 1900, p10.

Dundonald, who had been at school with Childe, read the burial service that night: “... we buried him close to a field of Indian corn. His men buried him affectionately and reverently in his clothes (Dundonald, 1926, p191). The reporter for the Daily Telegraph wrote “there were sobs and tears in that sad last farewell”. Childe had confided to his comrades a premonition that he would be killed. He asked them, as a favour, to put on his grave the words of Scriptural quotation “Is it well with the child?” ... “It is well.” (2 Kings iv. 26.) (Burleigh, 1900, p317). Childe was buried near the Mounted Brigade camp ... (approx.GPS -28.6592, 29.4364) Q and later re-interred at Rangeworthy Military Cemetery.

The British field guns had fired an average of 450 rounds apiece (Holmes Wilson, 1901, p69) without dislodging the Boers, one of whom wryly observed: “In the rifle’s jurisdiction, the casting voice is not with the artillery” (Schikkerling, 1964, p209).

Night of 20th January 1900.

By nightfall on 20th January the British occupied the entire southern crest of Tabanyama, about 10km east to west. Mounted piquets patrolled both flanks (Fig. 11). The Mounted Brigade bivouacked on the slopes of Bastion Hill, handing over to the East Surreys at dawn.

“The enemy’s marksmen had the range of this crest-line, and it was a dangerous matter to stand up even for a minute. Stone sangars were built and the companies relieved each other by the men crawling up the slope... When not in the firing line, we lay behind the slope in column, each company being protected by a parapet of earth or stone. Immediately below... the ground fell steeply, forming a ravine in which the cooks set up their field kitchens in comparative security” (Romer, 1908, p51).

A West Yorks private wrote: “... you must remember no one walked on Rangeworthy, everyone crept on all fours... the crouching attitude... was necessitated by the continuous stream of lead passing overheadB” (O’Mahony, 1910, p147).

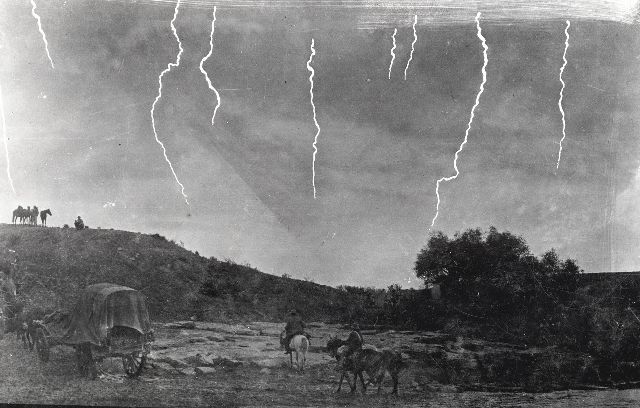

Throughout the night the Boers “worked feverishly at (their) entrenchments on the true crest, over which (they) frequently burst star shell” (Inniskilling, 1928, p420). By illuminating the plateau with magnesium star shells, the Boers stayed vigilant against a night attack (Fig. 10). Lt Riall of the West Yorks noted: “Great deal of sniping all night, built sangars” (Riall, 2000, p41).

Fig. 10. Magnesium star shells were used by both sides to illuminate Tabanyama at night. The Boer photographer has enhanced this image for effect.

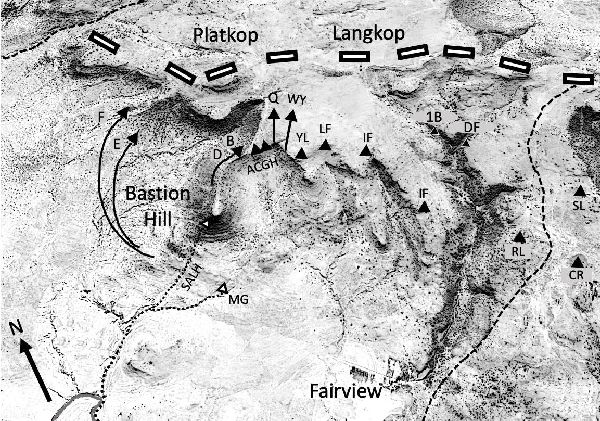

Fig. 11. Troop movements and British positions at Bastion Hill.

Dotted lines: route taken by SALH on 20th January.

MG = site where Winston Churchill deployed the machine guns.

Dashed lines: wagon roads to Ladysmith.

Black lines/arrows: Col Kitchener’s attack on morning of 21st January.

A-F: companies of the East Surreys: B, D, E, F advance towards Platkop while

A,C,G,H give covering fire.

Q and WY: The 2nd Queen’s (West Surreys) and West Yorks advance onto the plateau.

YL, LF, IF: The York & Lancasters, Lancashire Fusiliers, and Inniskilling Fusiliers give

covering fire.

1B and DF: The 1st Borders and Dublin Fusiliers shelter at the head of Battle Spruit.

RL, SL, CR: The Royal Lancasters hold Three Tree Hill, the South Lancashires Picquet

Hill and the Connaught Rangers Connaught Hill.

Before dawn on 21st January, Gen Hildyard ordered Col. Walter Kitchener (the younger brother of Herbert Horatio Kitchener) to take Platkop. Kitchener commanded the 2nd Queen's, 2nd West Yorks, and 2nd East Surrey. A Drummer of the West Yorks wrote: “Tommies favourite was the Colonel FW Kitchener and he knew it, and when leading his men he knew no fear; the troops would follow him anywhere” (Goodwin, 30 January 1900). Kitchener was overheard to say: “We are doing no good here... If I had my way I would rush across that open and get, if not would rush across that open and get, if not to Ladysmith, to Heaven anyway” (O’Mahony, 1911, p147).

The East Surreys led the attack: before dawn, F and E companies would march west in the plain below Bastion Hill, and climb the spurs south-west of Platkop. Simultaneously, B and D companies would skirmish towards Platkop along the flat summit of Bastion Hill. A, C, G and H companies would provide support by firing across the isthmus of Bastion Hill. To their right, the Queens and the West Yorks would advance, while further east, the Lancashire Fusiliers and York & Lancasters would support with rifle fire (Pearse, 1903, p11). Dietlof van Warmelo of the Pretoria Commando described the attack (1902, p27): “Towards morning, while we were still digging at the trenches, fire was opened across the whole line of battle. We imagined that we were being attacked, and jammed ourselves in the narrow trench. But as the attack did not come off, and the bullets flew high over our heads, we went on digging until daybreak. Then we noticed that the enemy were lying in a trench [donga] about 800 paces ahead of us. We fired a few shots at them, but saved our ammunition for an eventual storming”. Schikkerling (1964, p47) vividly described his anxiety awaiting the attack: “We would... have to endure the enemy’s artillery fire, until we could engage him with rifles. The minutes preceding a fight, after the enemy comes into view, and until the strife commences, are, for me, full of a nervous excitement. I know it cannot be fear; rather an intense anxiety to begin. Yet, at the same time, no farther from fear than red is from purple, sweet from sour, or tears from laughter. It is one’s sense of honour that upholds one, or perhaps, more often, the fear of being called coward. It is not a clean-cut fear of death so much as a vague terror in the air. I can understand that a nervous man, to be rid of the trial of suspense, would willingly take his own life at such a time”.

Platkop

The British assault on Platkop quickly ran into trouble: “Over the black plain, the grass of which had been burnt the day before, stream the three battalions, their khaki visible against the dark ground; another blast of musketry, and a shell or two, and figures fall; but the rush is not for a moment checked; a charge, a scuffle, and the ridge is reached, and a portion of it is British property. But this is of little use; another ridge, with an intervening plateau some 1,200 yards wide, is now seen for the first time. It is the Boer main position, and is immensely strong. To reach this, the third Boer line of defence, that glacis-like plateau, must be crossed. It is commanded by the heights, with their lines of low rock and earth redoubts, and trenches carefully prepared with overhead cover, so placed as to command all approaches with converging fire, and here and there with a cross-fire. The enemy knew what they were about when they let the British army plant its foot on TabaMyama [sic] ridge... ”

The East Surreys had light casualties (5 men killed, 23 wounded), because they were unable to get close to the Boers; Lt Porch was very severely wounded in the leg. There were some lucky escapes among F Company, East Surreys, Lt Col Harris and Capt Packman were both shot through the uniform.

The Queens advanced close enough for their officers to be preferentially picked off. Queens’ officers Capt Raitt and Lt Du Boisson were mortally wounded and Captains Bottomley, Sillem, Warden and Lieutenants Smith, Mangles and Wedd were all wounded. Lt Smith of the Queens had almost reached the large donga in front of Platkop, and despite being shot through the chest (the bullet coming out through his back), he continued to lead his men until he fell. He took cover near the donga till 3 p.m., when he crawled into it. He remained there till dark, when he managed to reach his own lines (Blake Knox, 1902, p48). Colour Sgt Kingsley’s Company of the Queens was caught in a cross-fire; both his officers were hit and he steadied his men and led them to cover; he was awarded the DCM and a scarf knitted by Queen Victoria (London Gazette, 1901, p2707). [See back cover page]. Officers of the Queen's and West Yorks called for volunteers, and with fixed bayonets tried to rush Platkop: “They were greeted by a deadly hail of Mauser bullets, followed by a steady roll of fire. The rush was disastrous; it could not succeed” (Blake Knox, 1902, p48).

The West Yorks had a similar experience: Capt Ryall was mortally wounded and 5 Privates were killed; Lt Barlow and 42 men were wounded. Lt Boyall led a section of 16 men of E Company to within 450m of the Boer trenches; Pte Morant was wounded carrying a message from Boyall, and Pte Powell wounded while bringing water to casualties lying out in the open (London Gazette, 1901, p950). “An advance ... was attempted but found to be perfectly impossible as it was an absolutely open Glacis leading up to their entrenchments ... as many as 300 rounds per man were fired, and the MG [Machine Gun] fired 7,500 rounds during the day” (West Yorks, 1902, p11).

At Hildyard’s request, the 19th and 28th Batteries rode from Three Tree Hill to new positions near Venters Spruit. Their 15-pounder guns came into action at midday, (at approx. GPS -28.64250, 29.45025) firing up the eastern side of Bastion Hill to Platkop, 3.5km away.

Shrapnel from these Batteries could not dislodge the Boers, who “had not wasted their time during the past three days, and had evidently made themselves bomb-proof shelters, behind which they were now safely resting, not disclosing their position till it became necessary for them to hold their trenches against the attacking infantryB we saw no sign of them, though the effect of their fire was very tellingB though we could not see them it was good to be able to fire at the hills which the guns were shelling and where we hoped the Boers were lurking (Kearsey, 1903, p16). The burghers became accustomed to shelling: “When the shell came directly towards one, the shrieking and screaming would grow louder and louder, then for a few seconds this would be succeeded by a rushing sound, the air would feel depressed and heavy” (Krause, 1995, p25) “Every bombardment weathered with a modicum of self-respect adds some iron in the blood and manliness to the personality" (Hofmeyr, 1903, p108).

From Three Tree Hill the attack on Platkop was visible through binoculars: “The aspect of the troops massed on the slopes was that of a great body of ants, large and small, the latter being men, the former animals and vehicles; for some ammunition mules, Maxim mules, and even ambulances, had climbed up. Outside the main body the specks grew thinner and thinner, and in the firing line they became invisible, except at times, when a thin, scattered line of khaki-coloured specks, almost particles, might be seen springing into sight from some cover, then flitting rapidly forward, and disappearing with the same rapidity as they threw themselves prone on the ground to recommence firing ... Each time the infantry became visible, it was possible through field-glasses to distinguish the dust thrown up in little clouds all round them as the enemy's bullets struck the ground. Very soon I noticed other specks, solitary ones and slightly larger, moving out. My glasses showed these to be stretcher-bearers, who had their work cut out for them on that hill. Throughout the day these stretcher-bearers, the majority of whom were... civilians... went forward, solidly and unflinchingly, to the very firing line, and could be seen bending over the fallen, tending and removing the wounded... unfortunately many paid dearly for their self-sacrifice (Blake Knox, 1902, p41).

About 6:30pm it began to grow dark, and the men who had been lying out all day on the plateau and in the large donga withdrew, attracting “heavy but ineffective fire” from Platkop (Pearse, 1903, p12).

Aftermath:

After 21st January, the British clung to the southern slopes of Tabanyama. They

had been sleeping in the open and in the same clothes since 16th January, and the

Boers were similarly exhausted. On the night of 23rd January, about a tenth of

Warren’s force, 1,700 men, were sent to climb Spion Kop. They hoped the

advantage of height would break the stalemate, allowing the main force to

capture the Fairview-Rosalie wagon road to Ladysmith. Spion Kop was taken, but

could not be held; it was abandoned after 24 hours. Intense fighting on Tabanyama

continued, and the Spion Kop disaster appears relatively unimportant in diaries

written at the time. The West Yorks’ experience was typical:

“Jan 22nd: Firing continued all day...

Jan 23rd: Firing still continued all day...

Jan 25th: Same position: still a heavy fire...

Jan 26th: Still in the same position; still a heavy fire”

On the rainy night of 26th January the British withdrew from Tabanyama and Bastion Hill, and re-crossed the Tugela; the battle of Vaalkrans followed 10 days later.

The British public were shocked by the news of their heavy losses on Spion Kop (322 killed, 563 wounded), and horrified by the propaganda photographs of their dead. Bastion Hill and Tabanyama (106 killed, 528 wounded) would soon be forgotten. The Boers, by contrast, remembered Spion Kop as a grueling 8-day battle ... during which 168 burghers died ... 58 of them on Spion Kop itself.

The battlefield today:

Tabanyama and Bastion Hill are on private land, without access for vehicles. Permission is needed before walking on the battlefield. Disturbing the sites or removing relics are forbidden. To visit Bastion Hill, turn off the N3 down the R616 towards Bergville. At about 18.5 km, turn left down a dirt road signposted towards Three Tree Hill Lodge and Rangeworthy Military Cemetery; immediately the silhouette of Bastion Hill will be recognizable to your left. The road passes the dongas along which Tobin and the SALH reached Bastion Hill, and where Winston Churchill deployed the machine guns. Rangeworthy Military Cemetery (the site of Maj Moir’s 11th Brigade field hospital) contains the graves of Maj Childe and about 80 soldiers. Rangeworthy farm has changed little since 1900. The battlefield can be visited from the west (starting near Easby farmhouse) or the east (starting at Three Tree Hill lodge). Boer trenches remain on Langkop and Platkop, as do British sangars along the southern crest of Tabanyama. Hindon, Slegtkamp and de Roos’s heroism was probably near GPS -28.61937, 29.46173. An obelisk marks the spot where Maj Childe fell (GPS -28.63344, 29.45912). The wagon road to Ladysmith is still there, as is the donga where the West Surreys sheltered (GPS -28.62182, 29.47069).

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to: Simon Blackburn, Tony Braithwaite, Barry Coventry, Ron Gold, Alan Green, MC Heunis, Jon Kaplan, Henk Loots, Fransjohan Pretorius and Arnold van Dyk.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org