The South African

The South African

By Brian Culross

Napoleon’s rise to power and fame was immense and apparently – as it must have seemed at the time – unstoppable. Yet his decline was catastrophic and complete, both for himself and his adopted country. Or was it? This 200th anniversary of his death (he died on 05 May 1821) is perhaps an appropriate moment to reflect upon his place in history.

It is unlikely the world we live in could ever witness an Emperor of Napoleon’s stamp arising again. (Unless, maybe, in some far-future, post-communist east...?)

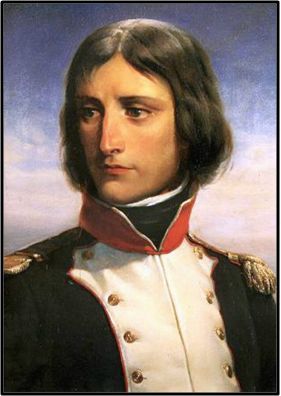

Napoleon Bonaparte, aged 23. Philippoteaux, 1792

[as lieutenant-colonel of a battalion of Corsican Republican volunteers.]

Napoleon’s influence and impact extended far beyond the narrow confines of military operations. Indeed, he left to history a legacy so vast, so complex, so polarizing, that it offers endless scope for debate, interpretation, re-interpretation, and discord. However, it is not difficult to agree with Talleyrand’s opinion that “He was certainly a great, an extraordinary man, nearly as extraordinary in his qualities as in his career”. [Markham, p.253] (We should, however, remark that Talleyrand’s is not a moral judgement – indeed, in the context of this essay, we must remember that while ‘greatness’ may embrace ‘moral goodness’, the two are not synonymous.) For contrasting modern assessments, we may match historian and military analyst Martin van Creveld’s: “the most competent human being who ever lived” against Corelli Barnett’s 1978 verdict that he was a social misfit, and a megalomaniac with an exaggerated reputation.

Napoleon is regarded as an heroic figure by many – especially but not exclusively by the French. (According to the web site samilhistory.com an admiring Winston Churchill kept a bust of Napoleon on his desk at Chartwell). Napoleon’s initial staunch defence of French interests gradually mutated into a desire to exert French – Napoleonic – hegemony over Europe. These intentions were constantly challenged – in the end, overturned – by European coalitions bankrolled and ultimately led by Britain, whom he regarded as his arch-enemy. Returning the compliment, the British regarded Napoleon as a megalomaniac tyrant, an oppressor, and a threat to their British (i.e., class structured) way of life. “If you don’t behave, Boney will come to eat you up” was the awful threat ringing in the ears of many a fractious British child during the early years of the nineteenth century. Even as late as 1900, 85 years after his final eclipse at Waterloo, historian W H Fitchett, writing a popular account of the Napoleonic Wars, could still stigmatize him (page 358) as “...a despot [at home], abroad he was a conqueror as ruthless as Attila”, and a ruler who “...suppressed the press ... abolished free institutions ... thrust his espionage into every household.” There is no doubt that in pursuit of his larger aims he could be ruthless – yet also indulgent in small matters.

What makes a leader ‘Great’? I suggest that to be ‘great’ – to be of imperial stature – he must possess not only an outstanding aura of leadership, but also its skills and ...ualities to a degree well above and beyond those of his followers. Radiating success and authority will make him respected; retaining a human touch will make him loved. He must command awe, loyalty, and willing obedience (at least from the majority). Napoleon qualified as ‘great’ on all these counts, a reputation unstintingly accorded him by the bulk of the contemporary French population. Only towards the end did this admiration begin to erode.

His achievements.

Firstly, he has been generally recognised, then and now, as a general of genius. (Even Wellington is said to have remarked drily, when he received news of Napoleon’s death: “Now I may say I am the most successful general alive”. [Neillands, p.280] His battle strategies are studied in military colleges every- where. Naturally he was not invariably successful in war, but succeeded often enough and often in sufficiently dramatic circumstances to acquire the halo of invincibility among his followers, who repaid him with a personal loyalty little short of love. Not infrequently he won his battles against seemingly impossible odds or circumstances. This ability to ‘snatch victory from the jaws of defeat’ was an impressive talent which awed his enemies as much as it encouraged his own forces. It was said on one occasion, “He had lost the battle by 4 o’clock, and by 6 o’clock he had won the war.”

Bonaparte as First Consul

Ingres, 1803-4

Secondly, whilst arguably an authoritarian, he was not at first a despot (except perhaps to some of those he defeated). He did believe in the French people – the proletariat at least – and while, inevitably, he demanded their loyalty and service, he also sought to improve their lot. The “Code Civil”, better known as the “Code Napoléon”, a revision, or in some cases wholesale replacement, of the archaic and aristo-favouring laws of the Ancien Régime, was written at his instruction – and with his active participation. He brought rational order to the crazy-quilt administration bequeathed to France by the early years of the Revolution, creating a centralised and uniformly run state. He promoted education and learning. Although in several respects a dictator, but almost uniquely for his era he often sought the approval of the French people through the mechanism of plebiscites. He was no democrat, but he curbed the powers of both the church and the aristocracy, whose excesses had borne so heavily on the lower strata of French society. In the pursuit of his stated dream of creating ‘but one people in Europe’, he endeavoured to bring French-style reforms to those European countries from time to time under his control, sweeping away lingering traces of feudalism. Reflecting the ideals of the Revolution, he promoted meritocracy over privilege (except, perhaps, where members of his own family were concerned!) and thus did much to open up opportunities for those of lower status. For instance, of his generals who were granted high rank and earned renown, Marshal Ney – “the bravest of the brave” – was the son of a cooper; Soult the son of a notary, Murat of an innkeeper, Lannes of a liveryman, and so on. Yet he also operated a harsh police state, and early on clashed with and bore down upon the Catholic church and other religious movements that seemed (to him) to encroach on his absolute authority – though his attitude mellowed in later years.

Thirdly, he was not merely a figurehead, a ‘decorative eminence set upon a silver throne’, but a truly hands-on improver of the nation’s organisation, a workaholic civil servant of extraordinary energy, capacity, and foresight.

Thus militarily, socially, and administratively he stood head and shoulders above contemporary rulers. If we seek his peer, we perhaps have to return to the court of Peter the Great to find one to compete with him, even imperfectly. If we look forward ... who? Franz Josef of Austria-Hungary? – he presided over the slow dissolution of an Empire that advanced nothing, achieved nothing. The Russian Czars – the Alexanders and Nicholas – barely clung on to power and defiantly refused to ease the lot of the masses. Stalin and Hitler wielded perhaps equal power to Napoleon, but who would award them even muted plaudits?

Lastly, the intellectual side. While by no means an academic, he was widely read. He particularly admired Goethe, who reciprocated by reporting that in conversation Napoleon ‘made observations at a high intellectual level’.

But we probably have to accept that as the years passed, power corrupted – if not his personal behaviour, then his clarity of vision. We need only point to his 1812 invasion of Russia: not only was it an insane project, but its planning and administration were criminally inadequate. For another example, his head-on attacks at Waterloo and in other late-period battles seem to have been the tactics of a general whose military acumen and judgement were in decline. Further, at Waterloo his leadership (perhaps due to illness) also seems to have been uncharacteristically sluggish [Black].

Despite having climbed, briefly, to the pinnacle of imperial power, Napoleon did not lose the ability to be a pleasant companion and a congenial guest. After his 1815 defeat and subsequent capture Napoleon fully expected to be permanently exiled from France – to a modest but well- appointed country house in the south of England perhaps? – and was dismayed when he learned it was to be St Helena. Nonetheless, he played the perfect guest aboard the HMS Northumberland during its ten-week voyage there. He became dispirited at his first sight of the island’s black volcanic cliffs rearing six hundred feet into the sky. “A disgraceful island” he called it, “a prison”. [Cronin, p.408] However, during his first few weeks on the island, staying in the home of an East India Company official while Longwood, his nominated (and rather modest) residence-cum-prison was refurbished, he charmed the 14-year old daughter of the house with his indulgent and avuncular behaviour. She retained fond memories of him for the rest of her life.

Longwood House, Saint Helena

David Stanley (Creative Commons)

Napoleon’s Death and Legacy

Napoleon’s death was not glorious. He did not expire on the field of a magnificent if posthumous victory, nor in a gilded setting, surrounded by sobbing subjects. Rather he passed away, a sick man, in unhappy confinement far away, far away from his still numerous admirers and from still loyal associates. It was, in a way, the death of a Promethean hero in chains, a hero obliged to breathe his last in damp and dull confinement (though it was a more or less proper, if sometimes mean- spirited, confinement, and given his previous ‘form’, perhaps the best he had any reason to expect). So his death in distant exile on St Helena, a speck in the middle of nowhere, lent pathos to glory, doing nothing to diminish his aura in the history books.

Civil legacy: The Code Napoléon, and the Europe-wide spread (imposition?) of Egalité, gave to France and Frenchmen a sense of greatness, destiny, and centrality – despite the Congress of Vienna’s attempt to restore the status quo ante bellum. Sadly, from 1870 onwards, this self-sense suffered terrible and repeated bruisings. Nonetheless, the France of today owes immeasurably more to the Napoleonic period than to any era that came before.

Military legacy: For a hundred years after his death Napoleon’s (frequently winning) emphasis on dash and élan became the central plank of French military thinking. This faith remained undiminished despite a few more cautious military minds (usually those of engineers or artillerists) pushing forward with defensive constructions along the Franco-German border during the last quarter or so of the nineteenth century. And despite a few voices (most famously Pétain’s) raised in protest as the new century arrived, forewarning that mechanisation – by which they mainly meant machine guns and artillery – would be more than a match for élan and the bayonet, the old ways prevailed. Only after piled hecatombs of poilus, whose élan proved not to be bulletproof, lay upon the fields of Northern France, in a slaughter which reached its climactic pinnacle in Champagne in 1917 – only then was adherence to Napoleon’s at last outworn military philosophy finally shaken off [Bruce, pp. 8, 10-11]. Yet that war, and the Second, epitomised an even more lethal Napoleonic-era introduction that did not die so easily: the ravages of total war.

Napoleon now lies in a place of honour in Les Invalides, Paris, evidence of the heroic status accorded to him by his countrymen. His remains are contained in an imposing sarcophagus of red granite donated by Russia, his one-time bitter enemy, further tacit acknowledgment of a greatness that transcended earthly squabbles. [See inside back cover.]

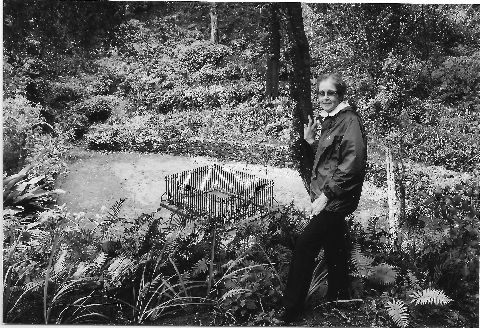

But when he died in 1821 the British insisted he be buried on St Helena and not returned to France. Hence he was interred – with the due solemnity of a military burial – below a simple slab just a couple of miles from Longwood House in what had been a favourite dell. General de Montholon, his aide and companion for most of the captive years, wanted the slab inscribed “Napoleon”. Sir Hudson Lowe, Governor and de facto jailer, insisted on “Napoleon Bonaparte”. They would neither agree nor concede. [Cronin p.440] And so the slab remained unmarked, mutely emblematic of the endless impossibility of ever reaching unanimous agreement about the position in history of the Last Great Emperor.

Napoleon’s original burial site

Acknowledgement:

In compiling this essay I received and gratefully acknowledge generous assistance from Lesley George, one-time Professional Officer at the National Museum of Military History.

REFERENCES:

Most of the details contained in this essay can be found either in the well-sourced Wikipedia article ‘Napoleon’ (accessed May 2021) or in Andrew Robert’s Napoleon: A Life (Penguin Group 2014).

Other sources:

Black, J., Waterloo, the Battle That Brought Down Napoleon (Icon Books, UK 2011)

Bruce R.B., Pétain, (Potomac Books, Washington DC 2008)

Cronin, V. Napoleon, (Collins, London 1971)

Fitchett, W.H.: How England Saved Europe, vol. IV., p.358 (Smith, Elder, London

1900)

Markham F, Napoleon, (Mentor NY 1966)

Neillands, R. Wellington & Napoleon: A Clash of Arms 1807-1815, (John Murray,

London 1994)

samilhistory.com: ‘Churchill’s Desk’, at

https://samilhistory.com/2018/05/05/churchillsdesk/

(accessed May 2021)

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org