The South African

The South African

By Dr Anne Samson

Durban, being one of South Africa’s main ports, was to play an important role during the First World War, while Pietermaritzburg, the previous capital and now administrative centre of Natal, was home to the biggest internment camp in the Union. Other Natal towns such as Dundee provided coal and other goods to support South Africa’s war effort. This is a summary of the role KwaZulu-Natal played in the 1914-18 war. A more detailed and referenced account, including names of individuals who served, can be found on the Society website at www.samilitaryhistory.org

On 31 July 1914 in anticipation of the declaration of war, the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) was put on alert, mobilising when war was declared on 4/5 August. Their role was to ensure the safety of the ports. Apart from German raiders threatening the sea lanes, enemy cargo became spoils of war and enemy ships could be taken over for used as transport and hospital ships. Neutral ships, too, needed to be monitored as they could carry messages and goods destined for enemy territories.

With the South African coast guarded, the interior of the Union needed to be put on a war footing. The Imperial Garrison, the British force left in South Africa at the end of the 1899-1902 war to help maintain peace, was to be recalled to Britain, all except a handful of men remaining after Prime Minister Louis Botha announced that South Africa would take responsibility for its own security. The South Staffordshire Regiment was based at Fort Napier in Pietermaritzburg. On the outbreak of war, they were on manoeuvres at Potchefstroom, returning to Pietermaritzburg on 6 August 1914. They were immediately granted leave pending further instructions but before they left on 17 August, they entertained the local community with the band playing at various patriotic gatherings. However, their departure was to have an economic impact on the city when the troops withdrew all their savings.

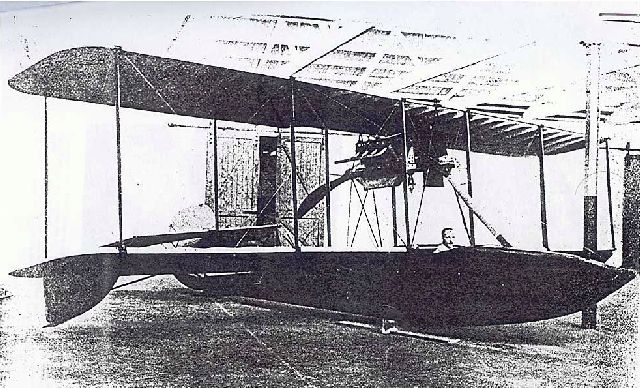

During this time, the German cruiser Königsberg was spotted 29 kilometres off the Durban coast. The Königsberg was of some concern as it had sunk the first British merchant ship of the war, the SS City of Winchester on 6 August 1914. Following this, the German cruiser moved south before heading for the Rufigi Delta in German East Africa where it was to remain, except for an excursion into Zanzibar Harbour on 20 September 1914 when it sank HMS Pegasus of the Cape Squadron. At that point Dennis Cutler, a Durban resident, was called to East Africa to track the Königsberg from the air in a Curtiss 90hp Flying Boat Type S. Cutler was recruited into the RNVR to make this official. Having located the ship, it was left to South African hunter Philip Pretorius (aka Jungle Man) to reconnoitre the ground. Meanwhile Cutler was taken prisoner in December 1914. The Königsberg was scuttled on 11 July 1915, making this the longest naval “battle” of the war.

Dennis Cutler in the Curtiss Type S

On 24 and 25 October, Fort Napier, which had been standing empty since the departure of the Imperial Garrison, saw new inhabitants. Two thousand German internees were brought from Pretoria. Over the war years, more were to be brought to the camp following the surrender of German South West Africa on 9 July 1915 and the anti-German riots of 7 May which had followed the sinking of the Lusitania. During the riots many shops and business owned by Germans and those with German (foreign) sounding names were destroyed in all major centres, including Durban and Pietermaritzburg.

Returning to 8 August 1914, the Durban Light Infantry and Natal Carbineers were mobilised to relieve the Imperial Garrison and protect South Africa, especially from ‘native attacks on Durban’. So wrote Smuts to Duncan McKenzie, the senior military officer in Natal who had played a significant role in ending the 1906 uprising. McKenzie was to go on to command the 1st and 2nd Natal Carbineers in the Maritz rebellion and German South West Africa campaign. The Natal Field Artillery also fell under his command. In April 1915, McKenzie’s force was involved in the attack on Gibeon where the German commander von Kleist was defeated but managed to escape. In the lead up to this attack in which McKenzie lost three officers and 21 ordinary ranks killed to 11 Germans killed, his force covered 322 kilometres in 12 days. During May, the Natal units returned home.

Natal Carbineers arriving in Cape Town at the end of the Namibian (German West Africa) campaign

Other Natal units which served in the rebellion and German South West Africa included the Natal Light Horse under Durban-born John Robinson Royston, and Botha’s Natal Horse commanded by JJ Botha, brother of Natal-born Prime Minister Louis Botha. The Durban Harbour tug, Sir John was in service in Walfisch Bay for a time.

Meanwhile the Durban Garrison Artillery protected the Durban Bluff with four 15-pounder guns. They were supported by the reserve unit, the Durban Coast Defence Force who supported communications and engineering. Some of the Durban Garrison Artillery joined the South African Heavy Artillery Brigade under Lieutenant Colonel JM Rose. Others accompanied Colonel Christian Berrangé’s Eastern Force into German South West Africa as K Heavy Battery, while N Heavy Battery served with Northern Force under Colonel Percival Beves. Later, men of the Garrison were to serve in France and East Africa as the 4th Battery Heavy Field Artillery, supported by Coloured and Black mule drivers.

With the end of the German South West Africa campaign on 9 July 1915, the South African forces still in the field were demobilised. Future involvement by South Africa had not been finalised in time to justify retention of the forces. Various discussions were underway which eventually saw South Africa supply an Imperial Service Unit for service in Europe under Tim Lukin. They were also to serve in Egypt. In November 1915, recruitment began for the East Africa campaign, Smuts having had a quiet word with various officers to not enlist with the contingent going to Europe.(1) The sending of these units to Europe and East Africa as Imperial Contingents meant that Britain effectively paid for their service, which protected the South African government from having to debate the issue in Parliament. The later Cape Corps would be recruited under similar conditions.

Numerous men from Natal went on to serve in the various theatres, with at least three of Bailey’s Sharpshooters being from Natal, Pietermaritzburg, Durban and Greytown. Bailey’s unit was the only privately funded unit from South Africa, the War Office having declined other offers of similar assistance. The units, although with local flavour, were essentially composite with men serving from all parts of the Union. However, the 500 strong Indian Stretcher Bearer Corps was a pure Natal-raised unit. They were trained by Captain Dunning who had previous Indian Army service and were to serve in East Africa where 23 lost their lives. Their base camp in Natal had been on Stamford Hill Road.

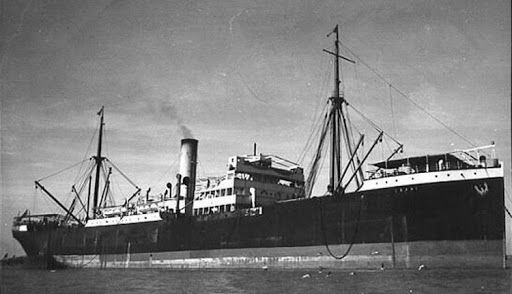

By all accounts, the Hospital Ship Ebani was staffed by the Natal Medical Corps between 13 August 1915 and 12 October 1919. This was after the medical unit had served in German South West Africa in the 6th Stationary Hospital in Swakopmund, also on the Ebani. Of the Ebani crew, only one name could be linked with Natal, that of Steward Ernest Denby French. Between 7 and 15 August 1914, Dr Dugald Campbell Watt, the brother of Cabinet Minister Thomas Watt, was on the Ebani. Campbell Watt was to feature quite prominently in the records of the South African Medical Journal during the war years.

The hospital ship Ebani which was medically staffed from Natal

In similar vein to the British Pals Battalions, South African education institutions record groups of alumni who served. Natal University College contributed 77 alumni, two being awarded Distinguished Conduct Medals and six Military Crosses. Thirteen were killed. Dundee High School also had a significant number enlist, the school Cadet Corps playing a role. Hilton had 371 old boys enlist of whom 47 were killed. Maritzburg College saw 91 deaths from those who served.

While it has not yet been possible to ascertain the numbers from Natal who served, it is easier to identify the deaths. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission Register lists 629 men and women as being from Natal. This number might well be higher as not all Natal links are recorded in the searchable items, such as that of Corporal 1630 Gysbert Johannes Roos of 3 SAMR (South African Mounted Rifles). It is in the additional information in the documents at the bottom of the CWGC record screen that one discovers he was the ‘Husband of Louisa Christina Roos, of Vryheid, Natal’. Unfortunately this level of record is not available for all who served in the Empire forces as it was not supplied to the War Graves Commission either by the family or the administrative bodies.

In addition to the numbers from Natal who served and died, Natal is the final resting place of 374 of the 4,159 First World War deaths buried in South Africa across 23 cemeteries. Durban (Stellawood) has the most burials with 196, Kokstad and Ladysmith both with two. The cemeteries, especially Stellawood, contain Nigerians, Gold Coasters (Ghanians), and Royal Navy as well as two of the German Navy. Specific cases and more detail can be found in the website article.

Close to the cemeteries were invariably military hospitals. There were also convalescent homes and camps. No 3 General Hospital had two bases, one in Addington and the other at the Drill Hall Section of the Durban Light Infantry while there was a ‘Native Military Hospital’ at Jacob’s. There were two convalescent hospitals, the Pietermaritzburg Hospital in the grounds of University College and Ocean Beach in Durban. Convalescent camps were based at Jacob’s for black Africans especially those returning from East Africa (EANative Labour Corps), and Ocean Beach on Marine Parade for white troops. Grey’s Hospital was responsible for the internees from Fort Napier who were hospitalised with enteric and typhoid. Sixteen were admitted of whom one died between February and May 1918.

There were other private homes in both Durban and Pietermaritzburg used for rest and housing of officers. A General Depot was to be found at Congella where local labour was employed, local labour also being employed in all the camps and hospitals as well as on the docks. The YMCA had a presence, providing entertainment and other services. Those who remained at home worked to raise funds and provide comforts for the men who were serving.

In addition to these activities, others who did not serve officially provided services which supported South Africa’s war effort. These included veterinary and medical practitioners, educators, manufacturers, farmers. While there were some who objected to the war as evidenced by the rebellion, others, including women, filled the gaps left by men who joined the colours. The war years were to see Mrs SA Woods voted into local office in Pietermaritzburg in 1915 and in 1917, two women were appointed Police Constables as part of an experiment. Yet others, such as the Padavatan Six, offered local support when floods hit the coast. While not all are specifically war related, the involvement of such individuals brings home the extent of Home Front involvement and the range of factors and conditions that had to be dealt with. These, which have not tended to feature in the historical accounts, include the impact of the environment on food provision, loading of ships, conditions in the camps and hospitals, and the health of the country.

Spanish Flu

In addition to the human cost of the war, the Spanish flu, which started spreading during the last months of the war accounted for 362 whites, 1,937 Indians/ Coloureds and 11,663 Black South Africans in Natal. This, together with the manpower loss caused by the war, was to impact on local economies, it being suggested that Pietermaritzburg had 34% of its population affected by the influenza outbreak. While Julie Dyer has looked at Health in Pietermaritzburg between 1838 and 2008, there is no doubt more to investigate concerning the immediate war years and their aftermath.

The war drew to a close on 11 November 1918, the date becoming the basis for the annual Remembrance Services. However, Natal has another event which few realise is a commemoration of those who gave their all, specifically in East Africa – the Comrades Marathon. This was set up by Vic Clapham who wanted to find a more fitting way of remembering fallen comrades than a memorial. The race between Pietermaritzburg and Durban covers 55 miles (89 kilometres) compared with the 1,700 miles (2,720 kilometres) he and his comrades covered over the East African veld and scrub between March and November 1916. To put this in context, a forced march would see men covering 20 miles compared with the usual eight to ten in one day. They would be carrying, if not the porter load of 40-60 pounds [30 kilograms], their approximate 8.8 pound or 4 kilogram rifle, and clothing, whilst on a reduced diet that was invariably unsuited to their condition of employment even if the full quantities arrived and suffering from malaria or some other debilitating bug through rain or shine. By the end of their march, few had helmets, greatcoats or uniforms left to offer any protection from the elements.(2)

To date, most South African accounts of the war are general, setting out the military contribution to the various theatres. Little has been written on the home front, the exception being Cape Town. It is therefore hoped that this provincial look at Natal’s multifaceted involvement in the 1914-1918 war opens up to a fuller view the extent of South Africa’s contribution to the conflict.

NOTES

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org