The South African

The South African

The importance of highlighting and comparing these two battles is they show the effectiveness of the Zulu warrior in broken terrain. This effectiveness was really only negated with the advent of the magazine rifle and its use by dismounted infantry as occurred in the Zulu Uprising of 1906.

Italeni (9 April 1838)

This battle was the result of the first Trekker offensive response to the murder of Piet Retief and his party (6 February 1838) and the subsequent massacre of those living in laagers in what is the present day Weenen area (16 February 1838).

The Trekkers had arrived in what is now KwaZulu-Natal as a result of the migration known to history as the Great Trek. Their arrival and setting up their laagers before negotiations with the Zulu King, Dingane, had been completed, was one of the triggers of the conflict that followed. Unfortunately for Dingane, his warriors failed to make a clean sweep of the laagers. Some managed to defend themselves and drive the Zulu warriors off. The atrocity did not instil fear, but a desire for revenge.

The Trekkers were in a precarious position. Reinforcements arrived led by Andries Potgieter and Piet Uys. They assembled a commando which numbered about 350 men. There were problems from the start. Potgieter and Uys were barely on speaking terms and the commando was divided into two groups or columns. This immediately posed problems for co-ordination. Nevertheless it moved aggressively, crossing the Buffalo River and approached to within 6.4 kilometres of UMgungundlovu.

Here in broken terrain they encountered some Zulu scouts.The scouts led them further into broken terrain. Effectively it was an ambush. There they encountered a large Zulu impi about 8000 strong.

Uys decided to attack on the right against the left Zulu horn. His charge broke through. Meanwhile Potgieter made a cautious charge against the Zulu left. The lack of co-ordination was sowing the seeds of disaster. Potgieterís attack was repulsed and he and his men retreated. The Zulu right horn now moved to cut off Uysís retreat. He bunched his men but eight were dragged off their horses. Uys broke through but stopped to sharpen his flint. He was mortally wounded by a thrown iZinti. He ordered his men to leave him. They did so, and at about 100 metres, looked back. Uys raised his head and was seen by his son Dirk, who turned his pony and raced back. He killed three Zulus before being killed himself. He was 15 years old.

The remnants of the commando arrived back at the laagers on 12 April 1838. Potgieter was blamed for the defeat and left for the Highveld with his men.

Ironically, the commando who won at Blood River ran into similar trouble on 27 December 1838 when driving cattle across the White Umfolozi River. They lost six men.

How is it that the Trekker commando mounted on horseback with muskets and rifled muskets ran into trouble when fighting against a Zulu impi armed with spears such as the iZinti and IKlwa? Obliviously the divided Trekker command played a significant role, as did the broken terrain. It is notable that the final driving of the amaXhosa out of the Zuurveld was carried out by British infantry. Frontier and later Trekker commandos had difficulty in operating in broken or close terrain. They did not have the weapons, skills, or discipline to do so.

This frieze in the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria pays tribute to 15 year old Dirk Uys who lost his life defending his father at Italeni.

Finally, it pays to take a closer look at the weapons involved. As Ian Knight has commented in his book The Zulus the iZinti could be thrown with some accuracy to about 50 metres, while the rifle or musket was effective to 100 metres. In broken terrain a fit man could keep up with a horse. However, when attacking a fortified position a warrior was at a disadvantage. This also applied to open terrain as the Ndebele found to their cost on the high veld.

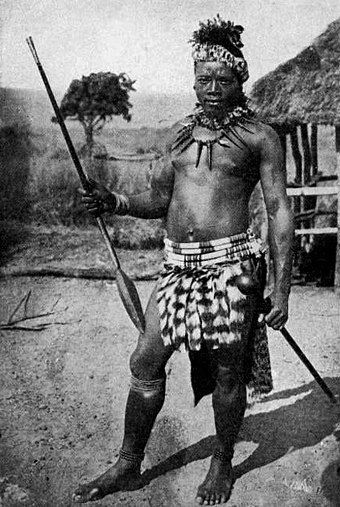

An iKlwa, a short stabbing spear.

A long throwing spear, an IsiJula or iZinti, as carried by a warrior along with his knobkierie.

Hlobane (28 March 1879)

The defeat of Dingane and the accession of Mpande led to the creation of KwaZulu and Natal as separate political entities. While Mpande ruled the relationship was stable and relations peaceful. In addition, the fighting in 1838 had created military stalemate and this also deterred hostility. Problems were under the surface. Their roots lay in Nguni secession customs and the fact that Zulu secession had been irregular for several generations. Cetshwayo was the designated heir but by the 1850s had become the focus for opposition to Mpande. Mpande tried to set up a counterweight. This triggered the first Zulu Civil War (1856). The two sides clashed at Ndondakusuka (2 December 1856). Cetshwayoís faction won. For weeks afterward bodies of the defeated dead washed up on Natal beaches. It was a grim portent.

Typical bush near Devilís Pass

By the mid-1860s Cetshwayo had restored relations with his father and he succeeded to the throne in 1872. He was confronted with several problems. There was a lingering land dispute with the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek. The discovery of diamonds had brought a destabilizing influence to southern Africa. This was combined with advances in weapon technology which caused the market to be flooded with obsolete firearms. Over three hundred thousand reached southern Africa alone. This was potentially a strong destabilizing influence.

Worse was to come. The later 1870s saw southern Africa hit by an El Nino drought. In addition, the period saw the attempt to implement Carnarvonís Confederation scheme. His agent was Sir Bartle Frere. The conjunction would trigger a series of wars in southern Africa.

The war which would lead to Hlobane was the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. A further factor was the unusually large number of British troops in southern Africa as a result of the 9th Frontier War (1877-8) and the annexation of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek. This gave Lord Chelmsford the resources to invade Zululand.

His plan was derailed by the defeat of his Central Column at Isandlwana (22 January 1879). His next move was to relieve the besieged garrison at Eshowe. To aid this operation he asked Sir Evelyn Wood, in command of the Left Column, to launch a diversion. This would precipitate the Battle of Hlobane.

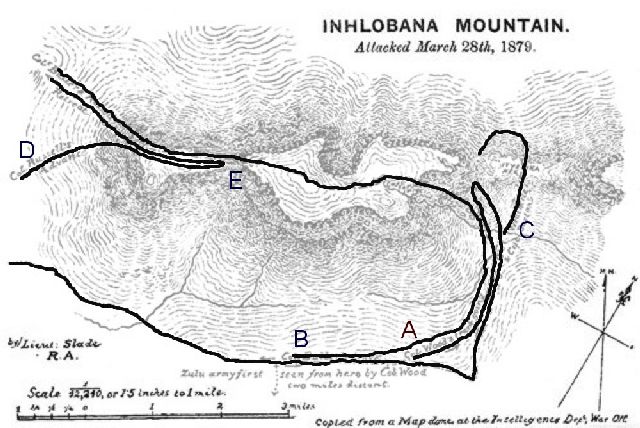

For the diversion Col Sir Evelyn Wood decided to raid the hilltop stronghold of Hlobane using his mounted troops.

To achieve his objective, he divided his force of some 1315 men into two groups. Already we are seeing a parallel with Italeni. This was compounded by incomplete reconnaissance. Wood had located two routes to the plateau, but he could not see the plateau. This added an unknown element to the plan. In war unknown elements increase risk.

The British Force was divided into two groups. The first was under the command of Redvers Buller and consisted of 675 mounted men, all irregular units, and a battalion of Col. Woodís African Irregulars. The second group was commanded by J C Russell, and had 640 mounted troops who were mostly irregulars with some regular mounted infantry and another battalion of Col. Woodís African Irregulars.

The plan was to attack using a pincer movement. Bullerís force would ascend by a stream on the eastern side and Russell by what was to be called Devilís Pass on the western side. Wood would accompany Russellís force as an observer.

There was a further factor which was to complicate matters. The main Zulu Army was on its way to Hlobane.

Original map by Lt. Slade RA enhanced to show

routes taken by British forces

KEY TO MAP

Letters at start of each route on map

A Col Bullerís route

B Col Woodís route

C Col Weatherly & Capt Bartonís route

D Col Russellís route

The two groups left Kambula on 27 March 1879 and rendezvoused at Zungwini Nek. Then Bullerís Force moved off at 03h30 on 28 March 1879 to move up the eastern side of Hlobane Mountain. The group had to fight through ambushes to get to the top. The Border Horse got separated in the dark and remained on the plain. Wood moved to check Russellís progress. At [the] top of Hlobane, Buller left a rear guard and began to gather cattle. His progress was halted at Devilís Pass.

Meanwhile Russell reached the top of Ntendeka. From there he spotted the Zulu army coming from the south and alerted Buller. Buller began to withdraw, and his force had been drifting west. He withdrew via Ntendeka, only to find that Russellís force was not there. He had withdrawn to the north-west. A mad scramble down Devilís Pass followed. Many casualties were suffered at this point.

During the retreat down Devilís Pass, Piet Uys saw his eldest son struggling with two led horses. Piet Uys went back to help his son and was speared by Zulu. This was a curious reversal of the Italeni situation. Meanwhile the Border Horse was trapped at Ntendeka Nek by a wing of the Zulu Army and destroyed. The commander F A Weatherley was killed with his son. Woodís African Irregulars, who had been abandoned, dispersed.

Buller spent the rest of day rescuing fugitives.

The defeat at Hlobane mirrored that of Italeni. The commanders had greatly underrated Zulu fighting capability in broken terrain. Poor reconnaissance and divided commands played a significant role. At both battles the short location ranges made the iZinti throwing spears more effective than in the open. The same applied to the firearms in Zulu hands.

It was these victories that caused the Natal Militia to act with care during the Zulu Uprising in 1906. The magazine rifle turned the Manzipambana (3 June 1906) action into a pyrrhic success for the Zulu rebels.

Bibliography

Laband J and Thompson P The Illustrated Guide to the Anglo-Zulu War, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal Press, Scottsville, 2004

Morris D The Washing of the Spears, London, Jonathan Cape, 1966

Stuart J A History of The Zulu Rebellion 1906, New York, Negro Universities Press, reprint 1969

Ian Uys, as a relative of Piet and Dirkie Uys, sent the following:

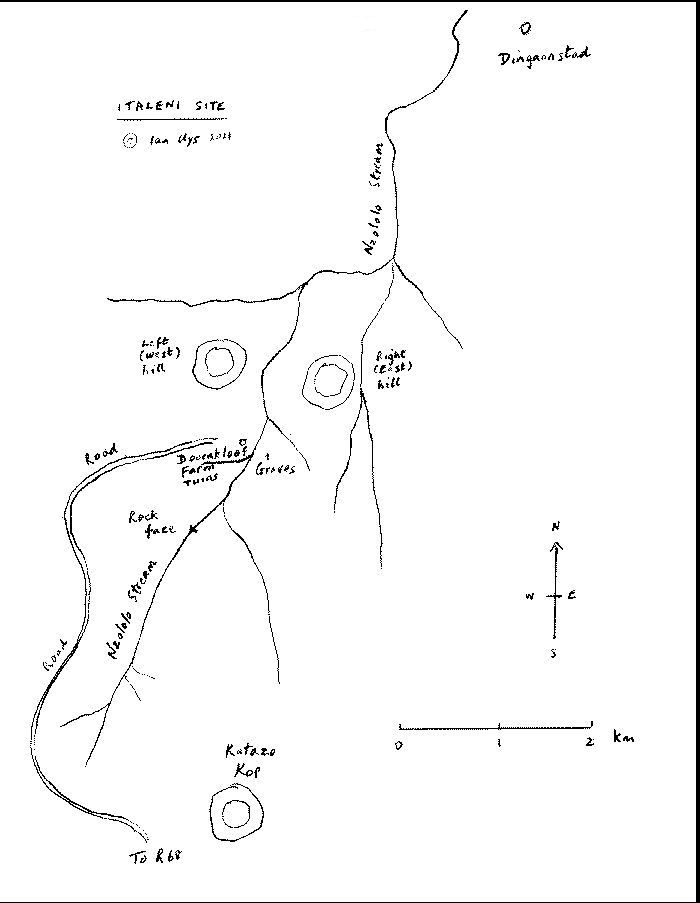

Italeni site map

The rock face is approximately seven kilometres south of Dingaanstat.

The Voortrekkers would have descended from west of Katazo Kop down the road route, which the Zulus used to travel to Dingaanstad (Umgungundlovu).

The pack horses would have been left in the level area near the site of the later farm house.

The Potgieter party attacked the left hill, then retired back along the route they had traversed.

The Uys main party attacked the right hill, then would have retired the same way as the Potgieter party.

Piet Uys was probably mortally wounded by an assegai and the Malans and Nels killed in the area near the later farm house.

Uysí small party were cut off and rode along the Nzololo Stream, which becomes progressively deeper with walls of three metres on either side.

The Zulus knew that Uys would encounter the rock face so could easily keep up with the party in the stream bed by running alongside on the river banks.

At the rock face the party would have clambered and rode up the left (east) side of the gully to continue their escape.

Piet and Dirkie Uys were killed in the area south of the rock face.

While Pietís bones were later recovered no trace was found of Dirkieís.

In about 1916 a Zulu who had been present at the battle as a boy gave Dirkieís powder horn to a cousin of Dirkie and said that the latter had been made soup of, to sprinkle over the warriors to make them as brave as he had been.

Ian Uys

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org