The South African

The South African

The Great Depression

The Great Depression, as elsewhere in the world, had a profound impact on South Africaís political landscape. At the time the Pact government was in power. This was an alliance between the National Party and Labour Party which was a result of the 1922 Strike.

The National Party was obsessed with being independent of the Commonwealth and especially of Great Britain. The Statute of Westminster which had been given legal force in South Africa had established the Union of South Africa as an independent and sovereign nation. Yet this was not enough for J B M Hertzog and the National Party. This led to a major mistake and error of judgement on the part of the National Party leadership. They decided to keep South Africa on the Gold standard as a sign of South African independence. The result was economic disaster matched only in recent times by the Presidency of Jacob Zuma. Political turmoil followed. Leading Nationalists demanded for the sake of the economy that South Africa leave the Gold Standard. Hertzog, with his obsession with independence, delayed action.

The political solution was found in an alliance between the National Party and the South African Party which came to be known as Fusion. One casualty of Fusion was the result of a Constitutional revision which reduced black access to franchise and removed black voters from the common voters roll. They were replaced by white members of Parliament elected by them. This happened in 1936 and blacks elected three white members of parliament. This would have an impact on South Africaís decision to go war.

Pro-Nazi Influence

One of the factors which would have a major influence was that Nationalists such as Oswald Pirow were pro-German. Pirowís parents were German immigrants and in 1938 he had made a tour of Europe which included Nazi Germany. Pirow himself was more German than South African and his family spoke only German at home. There were parallel but separate curiosities in Pirowís attitude -he was pro- German despite the Naziís anti-semitism; yet he was a member of the Nationalist party in SA despite their anti-Semitism based partly on a perception that Jews were not really South African.

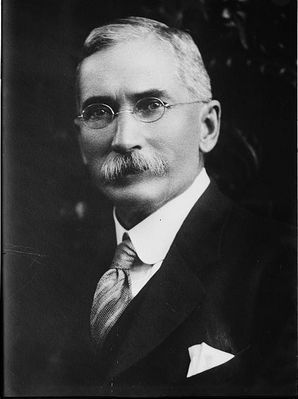

Oswald Pirow - a Pro-Nazi MP

Hertzog was also a Germanophile. How many other Germanophiles were in the Cabinet is uncertain. What is significant is Germanophilia blinded Hertzog to the realities of the international situation. What he failed to understand was that Germany had no respect for the rights of small nations. In this it had not changed in attitude from Imperial Germany. Hertzog had a lack of appreciation of freedom (Brookes and Webb p275).

Smutsí View

In contrast Smutsís view of Fascism and Nazism was developing into a realization of the real menace that these ideologies were to freedom and world peace. The Italian invasion of Ethiopia and the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia way-marked his increasing understanding. (H Giliomee: 2003: p439)

As Omer-Cooper has remarked the Labour, Dominion Party and Native Representatives would play an important role in the decision to go war. (J D Omer- Cooper; 1994; p1811)

Significantly the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia did not act as a wakeup call for the Germanophiles. In contrast it did for most aware and thinking individuals. Indeed the Germanophiles seem to have ignored it completely. The concept of neutrality which had been decided on during the Munich Crisis was unrealistic in view of Nazi German behaviour. In addition the Germanophiles completely ignored Smutsís very public expression of his views on the international situation. The invasion of Poland was met by Hertzog and his supporters with moral indifference.

J B M Hertzog

The Cabinet met on 2 September 1939. At this meeting Hertzog claimed that Hitler was trying to right the wrong of Versailles. This had the consequence that South Africa should remain neutral. Another minister predicted a bloodbath should South Africa declare war. Smuts then rose to speak. He explained why he had come to the decision that South Africa should support the Commonwealth and declare war on Germany. The meeting was then adjourned until the next afternoon Sunday 3 September 1939.

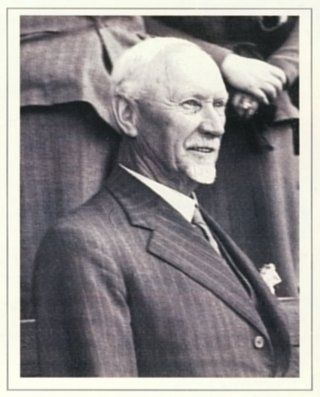

General J C Smuts in civilian garb

After breakfast on 3 September 1939 Smuts showed a rough draft of a motion he proposed to put to parliament the next day to a fellow MP. At the afternoon meeting the Cabinet was split from top to bottom: seven members supported Smuts and six Hertzog. On Monday 4 September 1939 Parliament was assembled to consider the Senate Bill. This was quickly dealt with.

Then Hertzog rose and proposed his motion of neutrality. The core of his argument was a link between neutrality and independence. He also stated that those who wanted to enter the war on the British side cared for British interests, not South African ones. He also said it would destroy South African unity. So far his speech had had a powerful impact.

Then Hertzog overplayed his hand. (D Oakes eds; 1994; p345) and according to Smutsís biographer, spoiled the moral effect by appearing to defend Hitler. (Hancock W K; 1968, p321).

Smuts then rose and proposed his amendment which was that South Africa should cut ties with German Reich and fulfil its obligations to the British Commonwealth. That South Africa should take the necessary measures to defend its interests and territory. That Parliament was convinced that South African freedom and independence is at stake and that force must be opposed as an instrument of national policy. A fierce debate followed during which D F Malan showed the same moral blindness as Hertzog. He claimed that that the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia was a defensive measure. (Hancock W K; 1968, p321-3) The vote was 80 for Smutsís amendment and 67 for Hertzogís motion. (Hancock W K; 1968, p323) By 13 votes South Africa retained a measure of moral stature.

On 6 September 1939 the Governor- General refused Hertzogís request for dissolution of Parliament, accepted his resignation and called on Smuts to form a government. South Africa was at war.

Bibliography

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org