The South African

The South African

My interest in this fort extends back many years to my meeting with Mr William Jervois, a descendant of the Lieutenant William Jervois mentioned in this article; the former was at that time involved in genealogical work for the 1820 Settlers Organisation, of which I was a member (and still am) in Port Elizabeth. I made an appointment with Mr Jervois to meet him in Grahamstown, and asked if he could please provide me with a copy of his distinguished ancestor’s Diaries during the period that the latter was stationed on the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony in the 1840s. This article has made extensive use of these diary entries.

This area of the Winterberg-Amathole Mountains, which had been populated predominantly by Dutch-speaking farmers, formed a natural citadel for the amaNgqika Xhosa warriors in their ongoing struggle with the British and Colonial forces for domination of the frontier. From this well-vegetated mountain fastness, it was an easy matter for the tribes to infiltrate the basins of the Koonap, Kat and Mankazana Rivers, from which rugged area they were able to issue forth into the low- lying land being occupied by other ‘invaders’. It was to counter this destructive practice that the first Post and its masonry successor were built.

Despite warnings from the settlers, the British colonial government in Cape Town had taken no action to provide any protection for the white settlers in this area. Finally, during the period Christmas 1834 – January 1835, ten thousand Xhosa warriors crossed the border and pillaged and murdered at will amongst the predominantly Dutch farm settlements.

That famous character from South African history, Piet Retief, had been given a land grant here by the British government in January 1830, in appreciation of his past services, and was again appointed ‘veldkornet’; he built a farm and relocated his family here from his long-time home Mooimeisiesfontein at Riebeeck East, about 90 kilometres to the south-west.

During this Sixth Frontier War of 1834 – 1835, Retief’s new farmhouse was destroyed; according to a comment from author Thelma Gutsche in an article titled ‘Authentic Memorials of True Pioneers’ (in Looking Back Volume 4, No 1, March 1964, page 13), the foundations of this house “have recently been discovered, covered in periwinkles, in a poplar grove on the farm Killaloe”, very close to the south side of the fort. But the first Post Retief Fort was established too late to help Retief during this crisis, as it was only constructed in 1836.

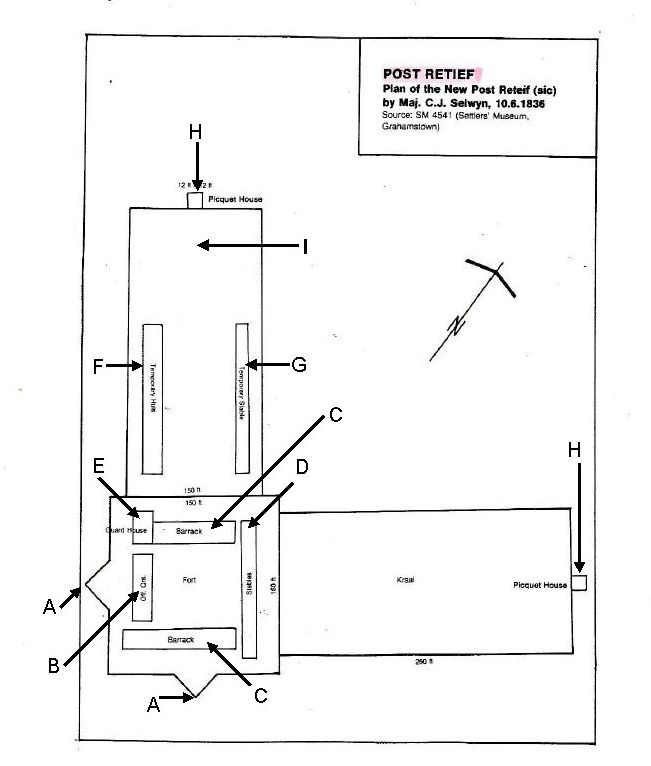

Post Retief Fort is little known and visited as a tourist attraction, perhaps due to its remote location which, on the plus side, may also account for the relatively complete survival of its buildings; views from the fort are also spectacular. The Post was originally established at the instigation of Cape Governor Sir Benjamin D’Urban, at that date with temporary wood and wattle-and-daub buildings (see Plan ‘A’); it is located at the northern extremity of the line of forts and posts which roughly follow the Koonap and Great Fish Rivers to the Indian Ocean in the south, and this has been termed ‘D’Urban’s Frontier Arrangement 1835’, following the 6th Frontier War of 1834-35.

The new Post was named in honour of Piet Retief, but it must have been a bit too close for comfort as Retief and his family were only to remain there for another two years before joining the Great Trek across the Orange River in March 1837, to escape as far away as he and his associates thought was necessary from British influence.

Post Retief and its history are well covered by Professor C G Coetzee in his book Forts of the Eastern Cape, published by the University of Fort Hare, circa 1995; as Coetzee was Professor of History at this University in the Eastern Cape, his book is one to which I frequently refer. In his section on Post Retief, Coetzee reproduces three successive layout plans of the fort buildings, as follows:

• Plan of the New Post Retief by Maj. C.J. Selwyn, R.E., 10. 6. 1836.

As the records state that the original wattle-and- daub fort was built in 1836, this is probably the plan for this first fort, as the dates correspond. One cannot be sure, as most or all the earlier buildings were removed when the rebuild took place about ten years later.

The plan shows a square section of 150 x 150 feet [about 2090 square metres] in the south corner, with triangular projections or 'bastions' on the SW and SE sides; this section is shown as containing an officers' quarters, two barrack buildings, stables and a guard house. From the fort extend two kraals to the NW and NE, both with dimensions of about 260 x 125 feet [each about 3033 square metres]; the former contains two long buildings marked "Temporary Huts" and "Temporary Stable" respectively, the NE Kraal being devoid of buildings. Both kraals were intended to have a 'Picquet House' of 12 x 12 feet [13.4 metres square each] outside the far end wall.

POST RETIEF

Plan of the New Post Reteif(sic)

by Maj. C. J. Selwyn, 10.6.1836

Source: SN4541 (Settler's Museum, Grahamstown)

PLAN A

KEY

A - Bastions; B - Officer's quarters; C - Barracks; D - Stables; E - Guard House; F - Kraal with temporary huts; G - Temporary stables in kraal; H - Piquet house - 12ft x 12ft; I - Kraal for 1500 head of cattle.

Researchers who are used to studying the British Frontier forts of the Eastern Cape during this period will be familiar with the term 'Picquet (or Picket) Tower', several of which have survived in masonry forts in this region to this day; these structures basically comprise a masonry gun tower of 2 or 3 storeys, with a parapeted flat roof mounted with an artillery piece on a wooden traversing carriage, which can defend the fort in any direction. I have never before seen the term 'picquet house', I have no idea what was its design or purpose; and we do not even know if these small extensions were constructed. The two Kraals incorporated into this design are a sensible addition, particularly in this farming region, as they are designed to accommodate large numbers of cattle and sheep, which a farmer in this area would be reluctant to leave on his premises when seeking shelter in the event of a rebel incursion.

Here I would just like to make a comment on the title of this fort. I have noted that any defensive structure built during the Frontier Wars of stone or brick is generally designated 'fort', but smaller and less important defencesespecially if of timber and wattle-and-daub, or of earthwork construction - are titled 'post'. It also appears that if the 'post' is subsequently rebuilt in the more durable materials, it retains its former title, presumably to avoid confusion due to a name change, as in this case. There are of course exceptions to this practice, as there seems to be no fixed rule.

Lt-Col Lewis, RE, visited the Post in January 1837, when the garrison was a detachment commanded by a captain. He recommended replacing the temporary buildings with a larger fortified barracks for 70 or 80 men. He also advised building a picquet tower with an artillery piece on top, as described above, but this sophistication was omitted from the final scheme, perhaps due to the additional cost.

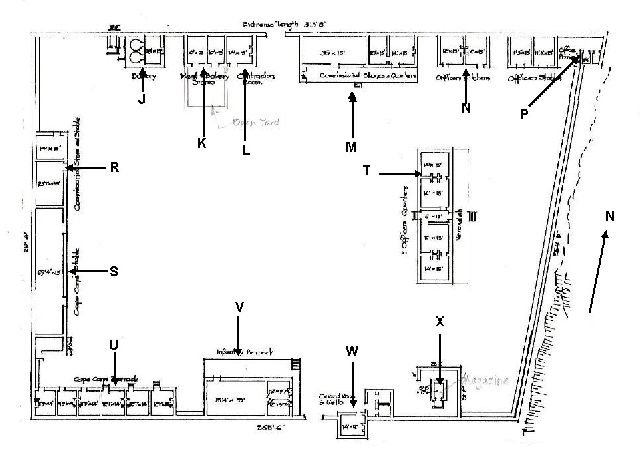

• B Plan of Post Retief circa 1845 (the present fort or ‘fortified barracks’)

This is the most detailed of the fort plans for Post Retief; I photocopied this plan from Coetzee’s book many years ago and, on my previous visits to the site, have always thought it to represent what is presently visible on the ground. The only structures that are indicated but not specifically named on this drawing are the Privies next to the Bakery and to the Cape Corps Stable (identified by their small size and screen walls), and the Magazine near the south-east corner, recognisable by its surrounding blast wall; however, oddly, both are properly named by Lt Jones on his much smaller plan of 1873, perhaps to rectify the previous omissions.

PLAN B

KEY

Along longer wall: J - Bakery;K - Meat and butchery store with later open yard; L - Contractor’s Room by North gateway;

Northern Gateway: M - Commissariat stores & quarters; N - Officers’ Kitchens; P - Officers’ privies;

Within the post: R - Commissariat store and stable; S - Cape Corps Stables; T - Officers’ Quarters;

Along shorter wall: U - Cape Corps Barracks; V - Infantry Barracks by South gateway;

Southern Gateway W - Guard Room and Cells; X - Magazine within blast wall.

The peripheral walls of this masonry fort enclose an area of 61540 square feet [5743 metres square], according to the measurements marked on the plan. This area was sufficient to accommodate local farmers and their families and livestock during the attack on the fort by the Kat River Hottentot rebels in 1851; the garrison and farmers were besieged for 4 days without food or water, until relieved by a commando led by Commandant W M Bowker, Dods Pringle and Captain Ayliff with a force of burghers and loyal Fingoes.

I had noted from the start that this drawing bears the inscription at the foot of the plan “Source: Personal field sketch book of R. Engr. Lt. W.F.D. Jervois”; this requires further comment on this officer, which I have deferred for the present time as the subject is large enough to form an article on its own.

The important question here is: was this fort designed by Jervois?

In my opinion, it is unlikely; according to his diary, he only visited this fort with Col. Piper and Walpole on Thursday 6 November 1845, arriving at 6pm after “a very hot ride” of 30 miles [nearly 50 kilometres] from Tarka. The following morning they left “Post Retief to Fort Armstrong, on to the Eland’s river and back again to Fort Armstrong. 31 miles.” I don’t believe that, after riding all that distance on 6 November, Jervois would have had the time or energy to draw up a plan of a fort of this size from scratch on 6 November, so the only explanation is that he must have risen early on the 7 November to measure the buildings and draw the plan, as he does not state a departure time from Post Retief. The fact that this plan is present in Jervois’ field sketch book indicates to me that the fort was in existence on the date of his visit.

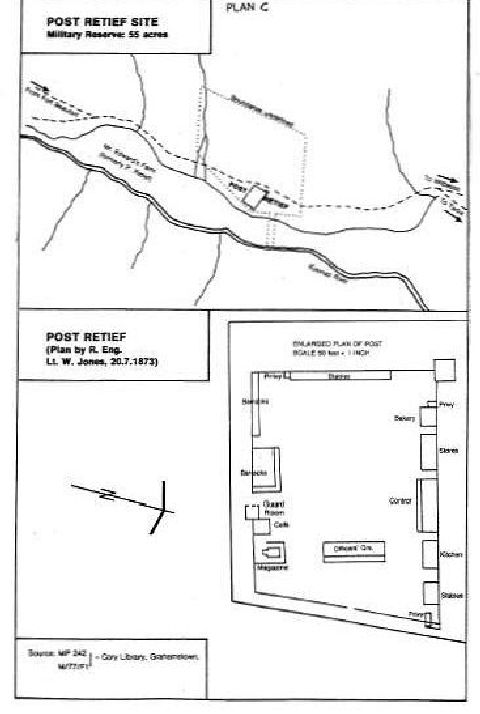

• C Post Recife(sic) Site plan and small layout plan by R. Eng. Lt. W. Jones dated 20.7.1873.

I have included this plan as the Post Retief Site Plan clearly shows the boundaries of the site, with a Military Reserve of 55 acres, and its location relative to the gravel access road (which today passes close by the fort buildings on the west side) and, equally or of increased importance, the proximity of the fort to the Koonap River to the east, including a narrow right of way to obtain that essential commodity for any fort garrison, a supply of water for drinking (especially) and washing. It is also interesting that a square projection is shown outside the NW angle of the fort; this can only represent a proposed Picquet Tower, as recommended by Lt-Col Lewis for the first fort, but again omitted from the final scheme. It is strange that this feature should be shown on Jones’ later plan, when there is no sign of a tower on Jervois’ layout, so the tower insertion cannot have been copied from the earlier scheme. The additional cost could be the reason once more for this omission.

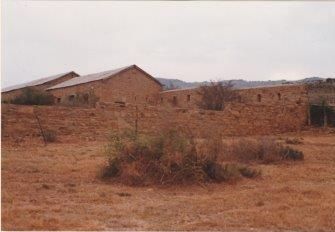

Early in 2017, I received a warning from an acquaintance, Dr Carl Kritzinger (who lives not far from Post Retief and takes a keen interest in the fort’s condition) that Post Retief Fort was falling into a state of disrepair. I mentioned this to my friend and fellow SAMHSEC member Pat Irwin and, in brief, we arranged to drive up to Post Retief to check out the situation. Pat’s wife Anne, also a SAMHSEC-member, accompanied us, and we arranged this excursion for 22 February 2017. En route, we called to check out the condition of the well-known Martello Tower in the town of Fort Beaufort, after I had received some disturbing comments on its condition from another of my friends. But that is another story...

We duly met up with Carl and spent several hours examining the condition of the buildings at Post Retief, the layout of which did indeed correspond in almost all respects with Jervois’ plan. Variation from the latter was the addition of three stone walls of an open yard in front of the two Meat and Bakery Stores (against the north perimeter wall), with an entrance at the north-east corner. When home again, I typed up a report on both visits and emailed them to the participants for record purposes.

My feelings on this occasion were that the fort buildings had survived in a remarkably sound condition, considering how little maintenance work has been carried out on them since the days of the former National Monuments Council. I am particularly grateful that Carl is now maintaining a watching brief on this important 19th century fort. However, there is no money to spare on the upkeep of heritage buildings these days, especially if they are of ‘colonial’ origin.

The graveyard

Close to the Fort, there is a cemetery containing the graves of soldiers who died, mostly in battles in this area during the 8th Frontier War of 1850-53. Prominent amongst these was, first and foremost, Lt-Col John Fordyce, Commanding Officer of the 74th Regiment, who was shot in the chest whilst directing his troops in the Waterkloof on 6 November 1851; he was popular with his men and was the most senior British officer to be killed in the 70 odd years that the British army was involved in Eastern Cape Frontier Wars. Fordyce was carried out of the action and laid under a tree, where he quietly passed away. The 74th suffered further casualties that day, including Lt Hirzel Carey (shot through the body and died at the head of his company) and Lt John Gordon who suffered musket ball wounds through both thighs; four NCOs and men were killed in action and 8 more wounded, of whom 3 later died of their wounds.

PLAN C

The dead and wounded were taken by mule wagon the 24 kilometres from the battle site to Post Retief, Lt Gordon especially in such great pain that he was removed from the wagon and carried by his men on a stretcher the rest of the way. Gordon was attended by a surgeon but lingered on until 10 November, when he succumbed to his wounds and was buried.

You will not find a memorial to Col Fordyce in this cemetery as in May 1852 his body, together with those of Carey and Gordon, was exhumed and taken firstly to Fort Beaufort (where Gordon was buried in the Roman Catholic cemetery); and then on a march of three days to Grahamstown protected by a detachment including three officers, with the band, drums and pipers of the 74th Regiment. On arrival, the men were welcomed and, after a few days, the two bodies were buried for the second time, in the presence of members of the Masonic Lodge (as Fordyce was a Freemason and the Lodge had requested the delivery of the bodies to Grahamstown for burial.) However this was not the end of Fordyce’s travels as his family asked for his body to be returned to England, so the body was again uplifted and carried over the waves to his homeland, where he was finally laid to rest in Kensal Green Cemetery in London. However there is a fine monument to Fordyce in the Congregational Church in Pearson Street, Central Port Elizabeth.

Ensign Frederick Ricketts of the 91st (Argyllshire) Regiment was shot in the chest on 14 October after pursuing the enemy for 16 hours in thick forest in the Waterkloof, and is also buried in the Post Retief Cemetery. I understand that Ricketts’ tombstone is one of the few on which the inscription is still legible.

The Waterkloof battle in which he met his end was taken from the present author’s article ‘Lieutenant-Colonel John Fordyce and his monument’ in Looking Back, Volume 45, November 2006, pages 8 – 19.

Sources

I am most grateful to the following publications and their authors for historical information obtained for this article:

Forts of the Eastern Cape, by Professor C G

Coetzee (c 1995, published by the University of

Fort Hare). I am especially grateful for the

opportunity to reproduce the plans of the fort

from this book.:

Plan A by Maj C J Selwyn 10.6.1836 came

from the Settler’s Museum Grahamstown (SM4541)

Plan B from the personal field sketch book of R Eng Lt W F D Jervois by courtesy of Mr W Jervois Albany Museum Grahamstown.

Plan C by R Eng Lt W Jones 20.7.1873 Cory Library Grahamstown

Looking Back (the Journal of the Historical Society of Port Elizabeth), especially Volumes 2 No 2 (June 1962), 4 Nos 1 & 3 (March and September 1964), and 13 No 4 (December 1973), by various authors.

I am indebted to Gordon R Everson for information on ‘The Graves of Post Retief’ in Looking Back, Volume 31 No 2, September 1992, pages 73 – 78.

Information on Lieutenant-Colonel John Fordyce and the Waterkloof battle in which he met his end was taken from the present author’s article ‘Lieutenant-Colonel John Fordyce and his monument’ in Looking Back, Volume 45, November 2006, pages 8 – 19.

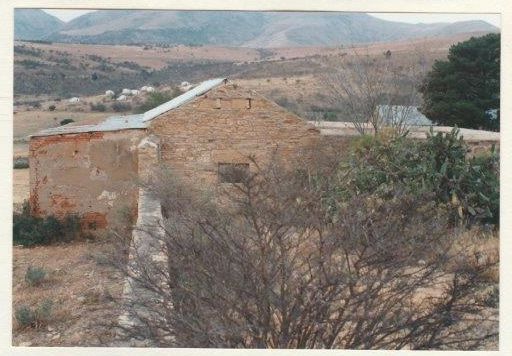

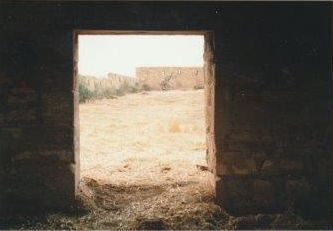

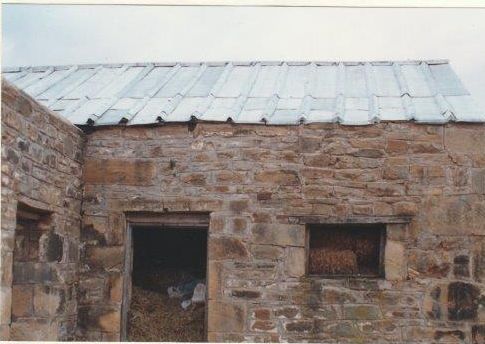

Colour photographs of Post

Retief taken in 1993 are shown on

the inside back cover of this

Journal.

All are courtesy of

Richard Tomlinson.

From NE, showing N wall in foreground,

inside of loopholed W wall

(Commissariat Store and Stable)

View E along N wall from NW corner,

to Bakery and Meat Stores and Yard

(Brick house on left is a later extension)

From NW, with N gateway on right and buildings

against inside of N perimeter wall.

(From L Officers' Stables, Officers' Kitchens

and Commissariat Quarters and Stores).

Looking N along E wall to NE Angle Tower.

(Officers' privies).

Looking through doorway of building

on N side towards SE corner of fort

Building against N wall - note Zinc roof

with zinc strips on triangular wood rolls.

(Contractor's room).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org