The South African

The South African

The Royal African Corps (RAC), which was stationed in the Cape Colony from 1817 to 1823, was an unusual regiment in its composition, functions and the way it was regarded and treated by the social and military establishment of its time. It was composed largely of ‘permanent punishment men’ who either had criminal records or who were considered to have criminal inclinations. It was also a multi- ethnic unit, including both Europeans and Africans within its ranks. Despite the anomalous title describing it as a corps, it was actually a regiment consisting of a single battalion varying in size from 400-700 men.

Sources

Source material on the RAC and related units is relatively sparse.1 The unit has no regimental museum and, with the exception of Crooks’ 1925 Historical Records of the Royal African Corps,2 no comprehensive history of it exists, nor is any substantive information about the unit to be found on the Internet. Primary sources in the United Kingdom include the Army Lists, The London Gazettes of the time, House of Commons Papers and miscellaneous documents and correspondence in the Public Records Office in London. There is also a manuscript diary of a Lieutenant J Kingley of the RAC in the National Army Museum in Chelsea, which I have not seen.3 The RAC is barely mentioned in otherwise comprehensive British military histories such as Fortescue’s 1923 multi-volume History of the British Army or more recently Boyden et al.’s 1999 ‘ashes and blood’: The British Army in South Africa 1795 – 1914. It is sometimes not mentioned at all, as for example in either Barnett’s 1970 Britain and her Army, or Holmes’ 2011 Soldiers, two otherwise very informative texts.

In South Africa, because of the regiment’s service in the Cape Colony, some primary source material is to be found in the Western Cape Archives and Records Service in Cape Town. Two South African historians, George McCall Theal (1837-1919) and Sir George Cory (1862-1935), have drawn upon these sources and those of the Public Records Office in London to reproduce some of the content in their publications. Most notably Theal, between the late 1890s and the early 1900s, collated and reproduced in printed and accessible format, several thousand primary documents, mainly letters, relating to the history of the Cape Colony. Known as the Records of the Cape Colony (in 36 volumes), they are today an invaluable source for historical researchers. Other than that, there are occasional passing comments and opinions in general histories relating to the Eastern Cape Frontier Wars, such as John Milton’s The Edges of War: A history of Frontier Wars (Milton 1983 pp70 & 72) and Noël Mostert’s semi-fictional Frontiers (Mostert 1993 pp473 & 475).

There is a small body of secondary source material in periodicals and magazines, and occasionally in books. The Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research has over the years carried several articles referring to the RAC, usually under the headings of ‘Disbanded’, ‘Condemned’ or ‘Penal’ regiments. They generally contain little about the daily activities of the unit or the lives of the men in it. Two articles containing letters written by serving soldiers in the RAC are included in a 2001 ‘Special Publication’ of this Journal (Boyden (Ed) 2001). The single most useful, insightful, and to some degree empathetic, article on the RAC is Major JJ Crooks’ ‘The Royal African Corps, 1800-1821’ in the 1917 United Services Magazine, a copy of which is available in the National Library of South Africa. As might be expected, some of the claims and statements made about the RAC in secondary sources cannot always be verified. With few exceptions the available information and commentary relating to the RAC is negative in tone.

Origin and behavioural problems

The unit, formed in England in 1800 was, according to the custom of the time, initially known as Fraser’s Corps of Infantry after its founding Colonel, John Fraser. As was often the case, a good part of the reason for undertaking such a task was for the founder to obtain a ‘majority’ (i.e. to become a major). Concomitant with this, Fraser was initially responsible, at his own expense, for fitting out and equipping the unit which he originally raised for service on the coast of West Africa. In 1804 Fraser’s Corps was amalgamated with several similar units, the whole being granted the title of the Royal African Corps and becoming part of the regular army with Fraser as its commanding officer. The uniform worn by the RAC was the standard British army red coat with white cross belts, white or grey trousers and the slightly bell-topped shako of 1816 with a straight plume. The facings were blue, and the regimental badge was the Lion and the Crown (Baldry 1935 p233; Tylden 1952 p136). They were armed with the standard Long Land Pattern flintlock musket, known as the ‘Brown Bess’, to which a 15-inch bayonet could be attached.

Notes

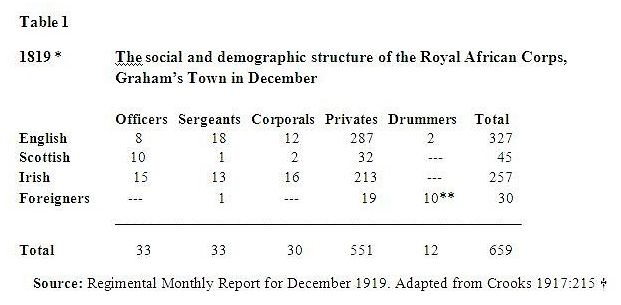

* Although the table indicates a situation some two and a half years after the RAC’s arrival at the Cape, the figures are probably reasonably representative of the unit at the time of its augmentation by troops from the 60th Regiment. We know of only a small number of fatalities suffered by the regiment during the Fifth Frontier War in which it had been involved, and no records of further reinforcements arriving from abroad could be traced.

** Black boy drummers from age 10 upwards were a widespread tradition in the British Army and one can presume that this was, at least in part, the case here.

† The original table from which these figures were extracted was signed by Capt. M J Sparks, acting OC,who was involved in the ill-fated Fredericksburg scheme. He was, according to Crooks (1923) to die in West Africa in 1824 – presumably either from ‘fever’ or at the Battle of Adumansu. See Notes 7 and 8.

An early indication of the character of the men constituting the regiment is given by Crooks, who

recorded the following personal communication with Colonel Fraser late in the latter’s life when he

was a General: 1926 p210).5

... when a captain in 1794, he raised men for a majority and then offered [them to the army] for

general service to get his lieutenant-colonelcy. ‘... And they took me at my word and gave me the

Royal Africans! A precious time I had with them for the next two or three years on the coast of

Africa! They were the sweepings of every parade in England, for when a man was sentenced to be

flogged, he was offered the alternative of volunteering for the Royal Africans, and he generally

came to me. They were not a bad set of fellows when there was something to be done, but with

nothing to do they were devils incarnate’. (Crooks 1917 p213).

Early in the 20th century, Crooks also examined aspects of the RAC’s history as part of a wider geographical and historical study of Sierra Leone, describing it as follows: The Corps was a disciplinary regiment as far as whites were concerned: That is to say, it was composed principally of deserters, convicts, [which often included culprits from the hulks4] and men whose sentence of punish-ment [including those with life imprisonment or awaiting execution] had been commuted for services in Africa (Crooks 1917 p213; Baldry 1935 pp233-235).

The Corps was a disciplinary regiment as far as whites were concerned: That is to say, it was composed principally of deserters, convicts, [which often included culprits from the hulks 4] and men whose sentence of punishment [including those with life imprisonment or awaiting execution] had been commuted for services in Africa (Crooks 1917 p213; Baldry 1935 pp233-235).

Often men who had been sentenced to severe flogging – anything from 100 to 1 000 lashes (Harding 1999 p135) – were given the option of joining a disciplinary regiment (Hill Those who did do so would in almost all cases have done it in complete ignorance of the service conditions they were about to face as there was virtually no public knowledge of life and circumstances in the disciplinary units. At times, the regiment also had ‘native Africans’, recruited mainly from liberated slaves in Sierra Leone. The latter were generally regarded as good troops, forming the backbone of the regiment, with a leavening effect upon the behaviour of their fellow European soldiers. There were also at most times a number of foreigners in its ranks including Italians and exiled Irish rebels (Cribbs & Marrion 1991 p18). Some indication of the demographic composition and rank structure of the RAC whilst in the Cape in 1919 is given in Table 1.

For the reasons above, the RAC early on became known as a ‘condemned’ or ‘penal’ regiment, being one of a group of military units described as such because of its recruitment pool and methods of recruitment.6 In describing recruits for this unit and those like it, Cribbs & Marrion (1991 p18) observe that:

Amongst these were the misfits and unfortunates who should never have been recruited, recaptured deserters, hopeless drunkards, bullies, thieves and worse ... The Army’s solution was banishment to the ‘condemned’ regiments serving overseas in the worst and most unhealthy stations, in the West Indies and tiny West African garrisons. Here heat and boredom, coupled with even harsher discipline, made life itself a misery from which only the mosquito and the effects of drink could bring release.

Descriptions such as this characterised the life of soldiers in the RAC. Its deployments from the time of its establishment, frequent name changes, and the re-organisation to which it was subjected, give some idea of the way the unit was regarded and treated by the military establishment of the day (Baldry 1935 p233; Yaple 1972 p12). The unit was on numerous occasions disbanded, amalgamated with, or split off, from other units, as well as being resurrected in various other combinations. The only constant in its existence was that it was always associated with criminal elements and hence had a permanent stigma associated with it – whatever its military performance.

In terms of its battlefield performance,

Fortescue (1923 p21), not surprisingly, has the

most to say. He opines that:

Occasionally a commanding officer was

found who, in virtue of remarkable character and

personality, could not only control these gangs of

ruffians, but even make them into docile and

serviceable soldiers. But naturally no good officer

would have to do with a ‘condemned battalion’ if

he could help it; and the off-scourings of the Army

under the sweepings of its officers made up a

dismal assembly.

In a different context, he adds that while

“[They]... may have been ... criminals ... double

dyed incorrigible scoundrels, with backs scarred

by the lash ... but when the time of trial came they

did their duty, and more than their duty, ... as

British soldiers” (1923 p388), yet concludes that

The Royal African Corps, unless commanded

by an officer of peculiar gifts was not to be rated at

a very high military value (1923 p391).

This remark perhaps says something about Lieutenant William Cartwright’s leadership at the East Barracks during the Battle of Grahamstown where he was in command of 60 RAC troops defending the families of the Cape Regiment (Irwin 2018 p114-116).7 For this he was mentioned in despatches by Governor Somerset to Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, and to Sir Henry Torrens, Military Secretary at the Horse Guards, as having defended his post with great intrepidity [and overwhelming odds estimated at 18:1] and drove back the enemy ... (Theal 1902a p194; Theal 1902b p204). However, as far as can be established and, despite their sterling defence at the East Barracks, there are no records singling out the RAC for praise or special recognition in this action. Two more recent comments come from Tylden (1952 p136) who, without giving his sources, states that The Corps had a good record in the field; and Davey (1992 p66) who, also without giving a source, states that To the credit of the Royal African Corps was the resolute conduct of a detachment during the defence of Grahamstown in 1819.8

Following Cribbs & Marrion (1991 p18)

Officers and NCOs were themselves a mixed bunch. Most NCOs were promoted from the ranks of other regiments, particularly the garrison battalions, and were tough characters. Some of the officers were also ex-rankers and some had won their commissions or promotion by acts of bravery.

The fates of officers serving in the Royal African Corps between 1800 and 1821, when the decision was taken to disband the regiment, are illustrated in Table 2 which offers an insight into some of these points. It is noteworthy that none are listed as ‘killed in action’ or killed by their own men which did occur in the army as a whole, from time to time.9 Hill (1926 p210), for example, records officers of condemned regiments sleeping at night with loaded pistols under their pillows, for fear of their own men.

In addition to the obvious factors underlying

the behaviour of the RAC, a further consideration

regarding their daily existence needs to be taken

into account viz. the unhealthy climes in West

Africa and the West Indies where they continuously

served, and where they were subjected

to high levels of infection from tropical diseases

(Curtin 1998 p5), with a consequently high death

rate – a situation which was crucial in moulding

the unit, the lives of the men and their behaviour.10

One source (Cribbs & Marrion 1991 p19-20)

suggests that it was partly as a result of the heavy

losses [due to disease, that]... most of the

remaining white troops [of the RAC] were sent to the Cape

of Good Hope in 1817.

Arrival at the Cape

Against this background, and with their

reputation which Theal (1908 p267) describes

as ‘evil’ travelling before them, when six

companies (Baldry 1935 p233), approximately

440 men, all Europeans, landed at Simon’s

Town in July 1817 under command of Lt-Col

Thomas Brereton (1782-1832), they were

decidedly unwelcome. The governor, Lord

Charles Somerset, supported by many of the

inhabitants of the Colony, had protested

strenuously at their deployment to the Cape

replacements for better quality troops, who

had been withdrawn as part of the post-

Waterloo cost cutting exercises by the British

Exchequer; an example being the 21st Light

Dragoons, who had been transferred to India

in 1817. Somerset’s concerns were soon

vindicated.11 According to Colonel John

Graham, Commandant of the Simon’s Town

Base at that time, upon disembarkation there

was mayhem in Simon’s Town, the soldiers

being responsible for theft, assault and sale of

their equipment, (as recorded by Theal 1902c

pp405-406).

Table 2 The fates of officers serving in the Royal African Corps between 1800 and 1821

Out of a total of 260 officers who joined the Corps from 1800 to 1821:

The RAC troops were then, notwithstanding further protest from Somerset, augmented by

225 troops, recorded in Theal (1902d pp57-58)as being ‘well conducted’, transferred from

the 60th Regiment, before it departed the Cape.12 This gave a combined strength

of about 650 troops, which is close to that recorded in the Regimental Monthly

Report for December 1819 as 659 officers and men. The RAC had in the interim suffered

relatively few casualties and had received no reinforcements.13 See also Table 1.

After their ill-disciplined behaviour at Simon’s Town, the RAC were rapidly marched

to the eastern frontier to perform guard duties at small redoubts and posts along the border,

where they remained for the rest of 1817 and until 1821 when the unit was disbanded. There,

their tendencies to marauding and theft once again found outlet, with local farmers and

burghers soon coming to regard them as more of a menace and danger to them than the

raiding amaXhosa clans were. Davey (1992 p65) records that On the eastern Cape Frontier

this regiment bedevilled relations there, and crimes of burglary, highway robbery and

as murder were laid at the door of some of its men. Brevet Major Rogers, Military Secretary

at the Cape, depicted them in a letter to Major General Torrens as a set of the most desperate

villains and worthless thieves and vagabonds that ever disgraced any country in the world

(Theal 1902e p58). In a letter to Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies,

dated 12th November 1817.

Somerset made urgent representation expressing the view that the RAC had caused

such terror in the interior that so far from being able to persuade settlers to repair to these

fertile districts, even those [farmers] who remained are taking measures for abandoning

a Country where lives and property are in imminent danger not only from their old

enemies, the [amaXhosa], but more so from those who have been placed there for their

protection. (Theal 1902f pp402).

Somerset added that atrocities were committed almost daily and implored Bathurst

that they might be replaced by better quality troops upon whom a commander could place

reliance (Theal 1902g pp354-356). One of many examples justifying his concerns is

recorded by Theal (1902h pp406-412), who notes that three deserters went on a spree of

robbing and killing civilians. When they were finally apprehended by a Khoi patrol, one was

shot dead and the other two were imprisoned in Uitenhage to await trial.14 The behaviour of

the RAC, Somerset con-sidered, also led to increased depredations by the amaXhosa

clans. In addition, there was fear of potential deserters aiding and abetting raiding by them

(Theal 1902j pp 403-404).

In December 1818, Colonel Brereton, then Commandant of the eastern Cape frontier, was

instructed to march to the assistance of Ngqika, a chief who was allied to the British, in

his dispute with the amaNdlambe (Irwin (2018 p113).15 He did so with a mixed force of

mounted burghers, Khoi Mounted Infantry and regular infantry which included the RAC. Given

their reported penchant for thieving and pillaging, it is not difficult to imagine the

depredations and behaviour of the RAC while on this expedition. The amaNdlambe retaliated by

raiding into the Cape Colony from January 1818 onwards and on 22nd April 1819 an

estimated 6 000 warriors attacked the embryo village of Graham’s Town. They were repulsed

by 333 British troops defending it, of which 135 were members of the RAC. For details of the

battle see Irwin (2018 pp114-116). The battle was followed by a punitive expedition into the

territory of the clans who, led by the amaNdlambe, had attacked Graham’s Town. The

RAC took part in this, but there are no specific records of their participation. The historical

records are generally silent on the daily comings and goings of the ‘Corps’ in the

aftermath of the post-battle expedition. They almost certainly continued with patrol work,

border duty and the manning of redoubts and there continued to be incidents of marauding

and thuggery.

Disbanding and departure

Sometime early in 1821, Sir Rufane Donkin, the acting Governor of the Cape

Colony while Somerset was on leave in the United Kingdom, received notice from the

Horse Guards that the six companies of the RAC at the Cape were to be disbanded

on 24th June.16 A few men were absorbed into the 38th

and 72nd Regiments, but the difficult question

which arose for Donkin was what to do with the

majority in a unit such as this. In the end a

number of solutions were sought.

Cribb & Marrion (1991 p20) inform us that after their operational service at the Cape

some of these men were, despite concerns, discharged for location in the Colony in 1821.

There were, however, those who for military reasons could not be discharged in the Colony;

could not lawfully return to England; and though fit for further military service, refused to

volunteer for other regiments. Following Cribb & Marrion (1991 p20) 160 of them were considered

too dangerous to risk ‘being set at large’. The worst, those who were unfit for

further service and could not be discharged in the Colony, were temporarily drafted into the

72nd Regiment, then based in the western Cape, with Donkin expressing the view that:

I have attached these worthless and

unmanageable people to a detachment of the

72nd Regiment at Graham’s Town, but I shall

take the earliest opportunity of removing them

to Cape Town as neither the settlers nor the

ordinary inhabitants would be safe in the

vicinity of such congregated banditti as these

men will form when collected. (Davey 1992 p65

quoting the Acting-Governor, Sir Rufane

Donkin).

There were two further attempts to deal

with the consequences of the RAC disbandment.

The first was a well-intended but short-

lived social experiment by Donkin. He

established a quasi-military village, which he

called Fredericksburg, inside the ‘ceded

territory’ between the Great Fish and Keiskamma

rivers, to settle some of the officers and men

from the unit (Boyden & Guy 1999 p 50).17

The project failed for a number of reasons, not

least of which was the mutual animosity between

Somerset and Donkin and the failure of

the British authorities to honour the agreements

made with the RAC officers and soldiers.

Details of these factors are beyond the

present remit.

The second approach was directed at the

portion of the RAC which had been removed to

the western part of the Cape Colony, where it

was self-evident that they should be kept at a

distance from the civil population. Somerset

and Major William Holloway (1787-1850),

Commanding Royal Engineer at the Cape, saw

the opportunity for the remaining RAC men

both fulfilling a public service at relatively low

cost, and being kept busy with hard labour. In

this capacity, they assisted in the construction

of the Franschhoek Mountain Pass which is

today still in use and has benefitted tens of

thousands of South Africans over the intervening

years. Apart from the memorial plaques

noted below, this is the only physical evidence

of the regiment’s nearly six-year sojourn in the

Cape Colony.

In 1823, with the Franschhoek Pass near

completion, the last of the RAC finally departed

from the Cape. Upon returning to West Africa

the remnant of the unit were, together with a

fresh draft of commuted punishment men from

England, absorbed into the Royal West India

Regiment but were shortly afterwards formed

into a new regiment called the Royal African

Colonial Regiment. This unit was later united

with three companies of the 1st West India

Regiment to become the 3rd West India Regiment

(Baldry 1935 pp233-234), which is the last we

see of the Royal African Corps: the unit simply

passed out of existence and no longer appeared

in the Official Army Lists. Its existence is not even

recorded in Swinson’s 1971 Register of the

Regiments and Corps of the British Army.

Thus far, I have only been able to trace two

monuments on which the name of the RAC was

recorded. One was the plaque on the

Franschhoek Mountain Pass, at the oldest stone

bridge in South Africa, which commemorated the

regiment’s hard work and participation in the

construction of the Pass. At the time of writing,

this has regrettably been stolen. It read as

follows:

This bridge was built as part of the first hard

road over the French Hoek Mountains by the

Royal Engineers assisted by soldiers of the Royal

African Corps. It was completed in 1825, and

except for a new surface, is one of the earliest

bridges in the Republic.

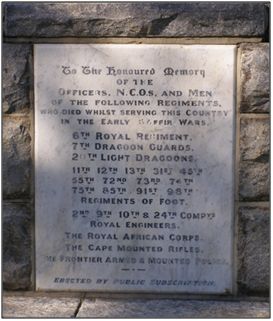

Figure 1: The tablet on the monument

The other example is a tablet on

Grahamstown’s monument to ‘The Unknown

Soldier’ which honours the memory of officers,

NCOs and men who died while serving in the

early frontier wars. There, the name of the Royal

African Corps is included along with those of

other units. See Figure 1.

In conclusion, we might return to the earlier

point about the paucity of detailed information

on the RAC. Given what we know about the

anatomy and function of the regiment, this is

not surprising. Several contingent reasons

present themselves.

The unit, its antecedents and successors

existed, for reasons explained, for only

relatively short periods (Baldry 1935 p234;

Yaple 1972 p12). Both NCOs and men had a

generally short life expectancy, and officers

tended not to spend a major part of their

careers in such units although some, as we

have seen, did, and died in West Africa in

1824, either from fever or in conflict. See also

Table 2.

In such circumstances, where ‘condemned’

units were largely isolated from family and

social connections, the keeping of diaries,

writing of letters and even the regular and

meticulous keeping of regimental records – the

very stuff of regimental histories in regular units

– would have been unusual and even rare. It is

also quite probable that among the rank and

file, apart from their social isolation, only a

small proportion (probably fewer than 10%)

would have been functionally literate, and

hence able to write letters or keep personal

records.18

There appears to be no record of a

regimental nickname, mascots, marches, or

songs although there is a single reference to a

regimental band (Fortescue 1923 p378). No

records of individual gallantry or awards could

be found. Likewise, no records of Battle

Honours could be located, although these

would surely have been deserved at some

points in the unit’s operational career. One

reference has however surfaced regarding the

presentation of colours to the unit by the

Governor-in-Chief of the West Coast of Africa,

Brigadier-General Sir Charles MacCarthy, who

had held the Honorary Colonelcy of the RAC

from 1811 to 1817. This act suggests he may

have had some regard for the unit, but whether

the colours were presented on his own

initiative or whether they had some wider or

official status attached to them is not clear

(Fortescue 1923 pp374-375). There appears to

be no firm record as to what the fate of any

RAC colours might have been, although there

is a sketch relating to the colours of its

‘successor’ unit, the Royal African Colonial

Regiment (Farncombe 1957 p137). To add to

this, there were however no long-term successor

regiments to preserve any memories or

records. There had also been little opportunity

to develop any regimental traditions which in

normal circumstances would have become

ingrained in the history of a unit.

In summary, the members of the RAC

were by and large society’s rejects, men who

had no stake whatever in the outcome of any

action they took part in, or any activities they

carried out, other than their own lives, the next

day and, regrettably in many cases, the next

supply of alcohol. It is difficult, through

modern lenses, to see the treatment of the

unit by the military establishment as anything

less than callous disregard or at best, as

indifferent neglect. In a sense, one cannot but

feel some empathy for these unfortunate

men.

Author’s acknowledgements

I wish to thank my wife Anne for content

scrutiny, constructive comment, and

proofreading.

NOTES

Brereton’s somewhat inept handling of the

Bristol Riots in 1831, for which he was

subsequently and controversially court

martialled, is sometimes irrelevantly linked to

his conduct of the ‘Raid’ in 1818. As a matter

of record, the court martial was predicated on the

notion that he was not harsh enough in

supressing the riots.

REFERENCES

Cribbs Don & Marrion Bob 1991 ‘The

Royal Africans: Story of the “banned”

British regiments’ Military Modelling 21 (4) 18-21 April.

Farncombe L G 1957 ‘Colours of the Royal

African Colonial Regiment’ Journal of

the Society for Army Historical Research 35: 136-137.

Milton John 1983 The edges of war: A

history of Frontier Wars Cape Town Juta.

Theal GMc (Comp) 1902c ‘Extract of a letter

from Col Graham to Major Rogers,

Secretary to the Commander of the

Forces at the Cape of Good Hope

[Lord Charles Somerset]’ under date

5th November 1817. Records of the

Cape Colony Vol 11 pp405-406.

Theal GMc (Comp) 1902j ‘Letter from Lord

Charles Somerset to Earl Bathurst 12th November 1817’

Records of the Cape Colony Vol 11 pp403-404.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's

Home page12 were transferred to other regiments: Many of these would have been through the purchasing

and selling of commissions.

126 resigned their commissions: These would have been men who left the army, most of whom

would also have sold their commissions. See for example the memoirs of Lieutenant John Shipp.

4 were superseded: These would be men who were replaced for one reason or another, sometimes

because they had not measured up to expectations.

1 was cashiered: In the armed forces, this usually implied being dismissed in disgrace because of a

serious misdemeanour..

61 died: Probably mainly of ‘fever’. There is no record of any officers being killed in action during the

period covered in this table. See Note 10.

56 retired on half-pay. In the British army and navy of the 19th century the concept of ‘half-pay’ allowed

officers to go into semi-retirement during periods of peace, when fewer of them were needed for active duty.

Such officers would receive half of their substantive pay which offered them some financial support while at

the same time providing a body of reservists when and if they were required for active duty.

Jan Joubertsgat Bridge

NMC 1979

‘To the Unknown Soldier’

in Grahamstown’s Old cemetery,

commemorating The Royal African Corps.

Baldry WY 1935 ‘Disbanded Regiments’

Journal of the Society for Army

Historical Research 14: 233-235.

Boyden Peter B, Guy Alan J & Harding

Marion (Eds) 1999 ‘ashes and

blood’: The British Army in South Africa

1795-1914 London National Army Museum.

Boyden Peter B & Guy Alan J 1999 ‘The

British Army in Cape Colony and Natal, 1815-1877’

in Boyden et al. 1999 op.cit pp 44-59.

Boyden Peter B (Ed ) 2001 ‘The British

Army in Cape Colony: Soldiers’ Letters

and Diaries, 1806-1858’ Journal of

the Society for Army Historical

Research. Special Publication No.15.

Crooks JJ (Major) 1917 Royal African Corps,

1800-1821’ The United Services Magazine June pp 213-221.

Crooks JJ (Major) 1923 Records relating to

the Gold Coast Settlements for 1750 to 1874 London Frank Cass and

Company Ltd.

Curtin Philip D 1998 Disease and Empire:

The health of European troops in the

conquest of Africa Cambridge Cambridge University Press.

Davey Arthur 1992 ‘Penal battalions at the

Cape, 1811 – 23’ Quarterly Bulletin of

the South African Library 47 (2) 63-66.

Dodd Arthur 1969 ‘The Royal African Corps

and Fredericksburg’ Coelancanth 7 (1) 40-50 April

Fortescue John W (Sir) 1923 History of the

British Army London Macmillan & Co Vol XI 1815-1838 Chapter 1:21;

Chapter 17: 370-388: Chapter 18:389-420.

Gordon-Brown A (Ed) 1941 The narrative of Private Buck Adams

(7th (Princess Royal’s) Dragoon Guards) on the Eastern Frontier

of the Cape of Good Hope 1843 – 1848 Cape Town Van Riebeeck Society

Originally published under the same title by WJ (Buck) Adams in London in 1884. See

also: Andrew Appleby (Comp) 1982 ‘Buck Adam’s narrative’ The Journal of

the Historical Firearms Society of South Africa 9 (4) 21-23 December.

Harding Marion 1999 ‘South Africa in words and images: Study collections at

the National Army Museum’ in Boyden et al. op.cit 1999 pp 131-177.

Hill RM 1926 ‘A condemned regiment’

Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 5:210.

Irwin Pat 2018 ‘The Battle of Graham’s

Town 22 April 1819’ Military History

Journal 18 (3) 112-117 December.

Mostert Noël 1993 Frontiers London Pimlico.

Rainier Margaret (Ed) 1974 The Journals

of Sophia Pigot 1819-1821 Cape Town Rhodes University / AA

Balkema Graham’s Town Series 3.

Shipp John 1844 Memoirs of the

extraordinary military career of John Shipp, late a Lieut. in His Majesty’s

87th Regiment London Fisher Unwin 2nd Edition.

Theal GMc (Comp) 1902a ‘Despatch from

Lord Charles Somerset, Governor of

the Cape Colony to Earl Bathurst,

Secretary of State for War and the

Colonies 22nd May 1819’ Records of

the Cape Colony Vol 12 p194.

Theal GMc (Comp) 1902b ‘Despatch from

Lord Charles Somerset, Governor of the Cape Colony, to Major General Sir

Henry Torrens, Military Secretary 22nd May 1819’ Records of the Cape

Colony Vol 12 p 204.

Theal GMc (Comp) 1902d ‘Letter from

Brevet Major Rogers, Military

Secretary to the Governor, Lord

Charles Somerset, to Major General

Sir Henry Torrens, Military Secretary,

Horse Guards 10th November 1818’

Records of the Cape Colony Vol 12 p57.

Theal GMc (Comp) 1902e ‘Extracts of a

letter from Brevet Major Rogers to

Major General Sir Henry Torrens,

Military Secretary 10th November 1818’

Records of the Cape Colony Vol 12 p58.

Theal GMc (Comp) 1902f ‘Letter from Lord

Charles Somerset to Earl Bathurst 12th

November 1817’ Records of the Cape Colony Vol 11 pp401-402.

Theal GMc (Comp) 1902g ‘Letter from Lord

Charles Somerset to Earl Bathurst, 21st

June 1817’ Records of the Cape Colony Vol 11 pp354-356.

Theal GMc (Comp) 1902h ‘Correspondence

and documentation concerning

desertion and subsequent criminal

activity – see dates in Note 13’.

Records of the Cape Colony Vol 11 pp406-412.

Theal GMc 1908 History of South Africa

since 1795 Vol 1, Chapter X: The Cape Colony from 1795 to 1828, the

Zulu wars of devastation, and the formation of the new Bantu

communities London Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

Tylden G (Major) 1952 ‘ Major-General Sir

Thomas Willshire, G.C.B., and the attack on Grahamstown on the 22nd

April, 1819’ Africana Notes and News 9 (4)135-138.

Wells JC 2012 The return of Makhanda:

Exploring the legend Pietermaritzburg University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Yaple RL 1972 ‘The auxiliaries: Foreign

and miscellaneous regiments in the British Army 1802-1817’ Journal of the

Society for Army Historical Research 50:10-28.