The South African

The South African

Leaving aside possible early Chinese use, the story of military observation balloons begins in revolutionary France in 1794. The story then shifts to the American Civil War, but returns to France in 1870, with the Prussian (or more strictly, the North German Confederation) invasion of that country.

It is generally agreed that the war was engineered by Bismarck, and that France was provoked to begin the hostilities. Her troops crossed the German border at the beginning of August 1870 – without balloons, which had been offered to the army by patriotic aeronauts, but turned down by a sceptical Minister of War. [Hildebrandt, p.142] But French planning and logistics were hopelessly outclassed by their opponent’s military skills. After a series of battles and encounters disastrously mismanaged by the French, their two regular armies were bottled up, one in Metz, the other in Sedan. Before long, Sedan surrendered, and amongst the booty that fell to the Prussians was Napoleon III, who had been leading the forces captured there. When this news reached Paris, a popular uprising overthrew his Second Empire, and the Third Republic was declared.

This upheaval delayed the Prussians not one bit, and within little more than two weeks they had encircled Paris.

The siege (which ran from 19 September 1870 to 28 January 1871 – some 18 weeks) is perhaps the most famous episode of the war, not least for the prominent part played in the saga by balloons. Indeed, the fame of the ‘Paris balloons’ has had two impacts on historical accounts. It has pushed the prior ballooning operations at Metz (minor though they were) into narrative obscurity, and has almost completely overshadowed the story of France’s attempts towards the end of the war to recreate the 1794 Compagnie des Aérostiers. In fact, the ‘Paris balloons’ mostly lie on the periphery of this narrative, for with a few brief exceptions they were used not for military observation but for civilian and postal transportation.

The Metz balloons

However, the Paris ‘balloon post’ was not a first, for Metz had adopted the same stratagem three weeks earlier when it, too, was surrounded and besieged by the Prussians. Over the ten days 05-15 September, two military pharmacists, Drs Papillon and Jeannel, built and released from the military hospital at Fort Moselle a series of 14 small balloons, each about 3x5 feet (roughly 1x1½m). [Cohn] This equated to a capacity of about 17ft3 (½m3). For ‘fabric’ the two doctors glued together gores cut from blue and white tracing paper, of which large stocks existed in the local military school (for use by the engineering and artillery students). From some source they acquired a supply of hydrogen, and filled with that their balloons could lift a payload of 1½ to 2 ounces (40-55gms). Each balloon carried a batch of letters written on small pieces of thin paper (consequently known as papillons, French for ‘butterflies’ – or were they named after the doctor?), between about 70 and 140 per balloon. It was an uncertain service: the first four balloons were lost; others drifted into enemy territory and their payloads captured, but Dr Jeannel later claimed he had “certain information” that seven of his balloons delivered their mail safely. Cohn estimates the service conveyed a maximum of 1500 messages.

The ‘pharmacist’ service was then superseded by a series of larger balloons built by engineer units. These were initiated at the urging (he claimed) of a British war correspondent, George Robinson of the Guardian, who was desperate to get his dispatches out of Metz. Eleven ‘engineer’ balloons were launched, each one carrying several thousand very small papillons – in all about 150,000 were sent out. Their arrival in friendly hands was of course a matter of chance, but some batches certainly made it to their addressees. The balloons were made with whatever material came to hand – in several cases merely white lining paper – whatever could be sewn or glued, and would take a coat of oil or varnish to lower the rate of gas loss. The service came to an abrupt halt on 03 October, when the Prussians smugly sent a batch of captured messages back to the French commander (General Bazaine). He immediately realised, with a start, that when they fell into enemy hands the papillons were potentially a rich source of intelligence.

Although the army’s engineers apparently at one time contemplated building a larger balloon that could be used to observe the Prussian positions, in the end nothing came of the suggestion. (It has to be admitted that apart from this still-born suggestion, the Metz balloons have little to do with ‘observation’, yet the writer feels they deserve to be rescued from obscurity!)

Ballooning at Paris

Balloons were already a familiar sight to Parisians before the war. Showmen vied with each other to enthral the public with displays of increasing – and sometimes fatal – derring-do. So when the siege lines finally closed around the city, thoughts immediately turned to the use of balloons for communicating with the outside world. In fact, two days before the investment was complete, Felix Nadar (the balloonist famous for taking the very first aerial photograph) was aware that the Prussian ring was closing in and had offered his services to the city as a reconnaissance balloonist. He had even lined up fellow aeronauts in an attempt to reincarnate the 1794 Compagnie des Aérostiers, but neither his personal, nor his Compagnie offers were taken up. However, on day two of the siege he did undertake a single, tethered reconnaissance of the Prussian lines. [Horne, p.123; Wikipedia “Siege of Paris”]

According to Bacon’s classic account of early aeronautics [Chapter XVII: The Balloon In The Siege Of Paris] two of the seven aeronaut balloons already in the city, though old and leaky, were patched up and flown on tethered observation missions, one from Montmartre, the other from Mont-Souris. Was it in one of these that Nadar ascended? [Mead, p.18, says there were three ascension sites, but does not name them.] Bacon says that when the weather permitted, each balloon made six ascensions a day – four in the daytime and two at night, sending their written observations to the ground in bags that slid down the tether rope. He concludes, however, that the net result, “from a strategic point of view, does not appear to have been of great value.” Hildebrandt [p.139] claims that “lights were used to signal from balloons [presumably from these early nocturnal flights] during the siege of Paris” and “gave satisfactory results”.

Four days into the siege, on 23 September, the aeronaut Duruof flew the Neptune, another patched-up balloon, out of Paris with 125kg of official dispatches on board.1 This was the first in a steady stream of such flights that took place throughout the next seventeen weeks of the siege – on average between three and four a week.

So steady a stream, in fact, that on the 26th a ‘Balloon Post’ service to the outside world was officially inaugurated.2 Thus though Paris was only following in Metz’s footsteps, it did so on a far grander scale. Some 66 balloons were sent out in total (all manned, except for one). Most carried post and dispatches – 11 tons in all, including about 2.5 million letters (which netted the authorities a sizeable income!). They also conveyed 164 passengers to freedom. The most famous of these was Léon Gambetta, sent out at an early stage to set up a sort of ‘mirror government’ in Tours. Only five of the ‘Paris balloons’ fell into Prussian hands, though two others were lost at sea. [Horne, pp.130-1]

The seven worn and leaky balloons already in Paris when the siege began were soon expended, since the balloon flights were a one- way traffic, outbound only. More were needed, and a balloon production line – for such it was – was quickly organised by the veteran French aeronaut Eugene Godard, assisted by Nadar. The main workshops were set up in the by now idle Gare d’Orléans (under Godard) and Gare du Nord (under Nadar).

Single trip ‘throw-away’ balloons these may have been, but they flew, and their constant passage overhead was an equally constant irritation to the Prussians. As had been the case in the American Civil War, every balloon was subjected to furious fusillades from the troops below, and again, as in that war, the net result was merely a waste of ammunition.

But problems are opportunities in disguise, as Alfred Krupp knew well, and Prussian frustrations led him to design a novel solution, and his rather primitive ‘balloon gun’ began the era of anti-aircraft artillery.

Paris fell on 28 January 1871, but that was not the end of France’s 1870-71 ballooning story.

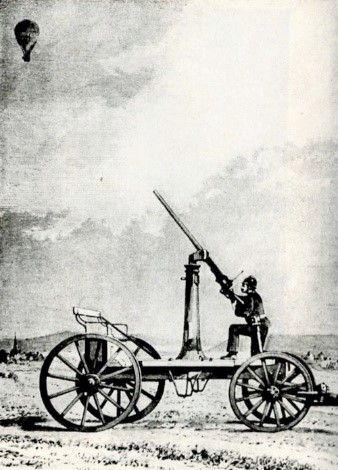

The KRUPP Balloon Gun

The First Anti-Aircraft Weapon - An impression of the gun in use.

The artist has exaggerated the height of the plinth by

about a third

to make the firer’s position look less awkward.

Tissandier flies for the Army

One of the earliest aeronauts to fly out of Paris was Gaston Tissandier. His personal balloon, Le Céleste, was small, old, and leaked like a sieve from long use, but paste pot and paper made it adequately serviceable in the short term, and on 30 September, it carried him safely out of the capital. During October and into November, having met up with his brother Albert and Albert’s balloon the Jean-Bart, Tissandier3 bent his energies towards devising means whereby balloons could be flown into Paris. There was no shortage of ideas – neither his own nor those of would-be inventors of varying degrees of insanity – but the means to achieve effective dirigibilty were not yet to hand. Inward flights, though attempted, never succeeded. Frustrated at these failures, Tissandier was now ready to offer his services as a tethered observer to the Army.

Gaston Tissandier

In fact, Tissandier had urged the revival of a military balloon unit several months before the war broke out, but when its shadow was already falling across France’s future. [Tissandier, p.vii& p.73ff] His urgings had (of course) fallen upon complacently deaf ears, but now, in the field and in the face of the foe, authority had become far more receptive. Tissandier tells us that even before he had given up the idea of creating a ‘return service’ into Paris, the ‘mirror’ Government in Tours had arranged for an ad hoc group of balloonists (including some of the hastily-trained sailors who had successfully flown Gaston out of Paris) to begin Tissandier tethered observation ascents from Orléans, from which the Prussians had recently been expelled by the Army of the Loire. Equipped with a newly made silk balloon, the Ville de Langres, they had made several trial ascents. In the course of these, they had discovered the hazards of ‘walking’ an inflated balloon through urban areas (i.e., Orléans) laced with telegraph wires and other overhead obstructions. In addition, their path through streets of essentially medieval origin was sometimes so narrow as to permit only one group of handlers, and hence only one tether rope, to pass. (Two tethers was the norm to ensure adequate control.)

Once the Ville de Langres had arrived at its chosen ascension site, wooden cages were filled with whatever rocks were to hand to act as anchor-points for pulleys. The tether ropes, passing through these, were released or hauled in by hand (using teams of around thirty men per rope); no windlasses seem to have been used. A telegraph key carried in the basket permitted instant communication, not only with the ground party, but with the government ministers in Tours.

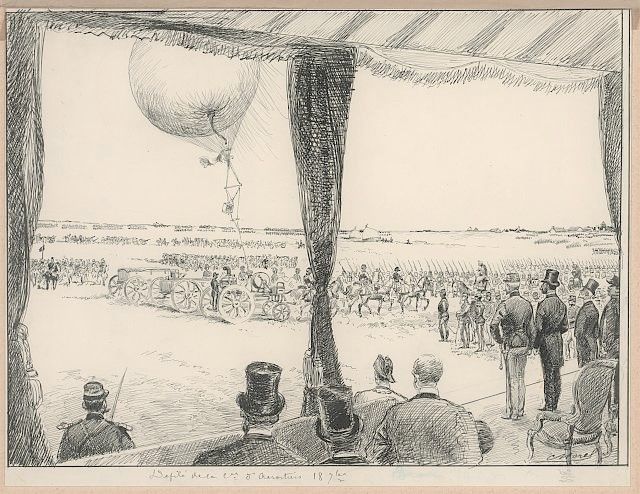

“Drawing shows a parade with one of the balloons used in the Siege of Paris (1870-71)

and a group from the Compagnie des aérostiers militaires,

with officials in a reviewing stand in the foreground.”

Author’s NOTE:

The nearest wagon carries the hand-operate winch.

The exact date of the parade is not given, nor the occasion.

Image and caption from US Library of Congress archives.

After several ascents, the Ville de Langres was losing buoyancy, and went back into Orléans for topping up. On 2 November, once more properly filled, it was sent forward into the French lines at Gidy. Here, on the 21st, a staff officer was detailed to join the balloonist Duruof for an ascent. At 40 feet (12m) above the ground his nerve failed and he decided he would rather be back on terra firma. But, as Tissandier remarks, “one can be at once an excellent soldier and a very bad aeronaut”, and the order he barked out in his confusion was “Throw some ballast!” The balloon, being already in positive buoyancy, naturally now went up like a rocket. Tissandier does not record the officer’s reaction, but goes on to say that, the wind being particularly strong that day, the balloon was flinging about liken out-of-control pendulum, putting such strain on the concentration hoop that it began to break. At any moment the basket and balloon could have become separated. Quick- thinking Duruof immediately yanked on the valve rope and the deflating balloon rapidly but safely delivered its passengers to the ground. We are not told how the staff officer’s career progressed thereafter! [Tissandier (1871), p.77]

On the same day that this little drama was playing out, Tissandier and his brother, along with the Jean-Bart, arrived in Orléans. Here (if the tenor of his account is to be taken at face value) Tissandier assumed the role of leader of what now amounted to a small, if unanointed, Compagne d’Aérostiers. They set up headquarters a little way out of Orléans, at Chateau Colombier, bringing to it both balloons and all their supplies and equipment. The latter apparently included a hydrogen generator utilising the action of sulphuric acid on zinc.

On 30 November they set out to walk the Jean-Bart to the Loire Army’s headquarters at Chilleur (now Chilleurs-aux-Bois) in response to a summons from General d'Aurelles, the army’s chief. After a terrible day – the men on the tether ropes slogging through mud and fighting against a violent wind, their hands raw and their arm muscles on fire, and Tissandier and his brother taking turns to freeze half to death in the basket – they arrived after dark in the village of Rebréchien. They had taken all day to cover half the journey – no more than eight or so miles (12-13km). Before turning in for food and rest they dug a pit in which to settle the Jean-Bart, weighting the basket with rocks and tethering the envelope firmly all round.

Alas for their hopes of impressing the sceptical General d’Aurelles with their reliability. During the night the wind redoubled its ferocity, the Jean-Bart ripped wide open, reduced to a tangle of rope and flapping cloth. They trudged gloomily back to Colombier with the corpse of Jean-Bart bundled up in a wagon.

Yet far from being reproached for their failure, they were praised for their attempt, and more balloons were found for them. One of these, bearing the rather clumsy name of République Universelle, was inflated in Orléans, and walked, on 03 December, to the balloonists’ base at Colombier. Next day, they set out, once again, towards Chilleur – but too late. That night, the Army of the Loire was routed and streamed back towards Orléans with the Prussians on its heels. Tissandier and his men waited in vain for orders, in the end leaving them no alternative but to join the flood. With most of their equipment they escaped Orléans on the last train to leave, and travelled south-west, towards Tours.

Compagne d’Aérostiers reborn.

The next decision was far more purposeful. It was that the balloon resource, hitherto operated by civilian aeronauts, should become a proper military unit. As a first step, the two Tissandier brothers and six other members of their ‘corps’ were assigned the rank of Captain, at a salary of 10 francs per day. Each Captain was given responsibility for one of the various logistic, maintenance and operational facets of the unit’s proposed work. Initially, four balloons were established, each one with 150 militia men as ground crew. A uniform, reminiscent of that worn by sailors, was issued.

This optimistic picture was then spoiled by the appointment of two placemen as colonel and commander. According to Tissandier’s account of this decision [p.117] (which drips with frustration and anger) these two knew nothing about ballooning (except that it entitled them to a generous salary) and made no attempt to learn. They based themselves in distant safety and comfort at Poitiers, impatient to receive their honours for such loyal and distinguished service – honours which, naturally, came through in due course.

On 09 December, the now officially established balloon corps set out by rail on its first mission towards Blois, 32 miles (51km) north-west of Tours. Once again, a Prussian attack frustrated their plans, and they arrived to find themselves in the middle of a retreat. Back to Tours – but Tours was being abandoned, and they were ordered on to Le Mans. Here, in a chaotic camp at Conlie, they were attached to the Army of Brittany, under the command of General Marivaux. He expressed enthusiasm for the balloons, and on 17 December they began inflating the Ville de Langres. On the 19th they made the first of several ascents attempting to discern the Prussian dispositions, but fog largely frustrated them. The next day was clearer and they had a grandstand view of General Chanzy’s impressive-looking army -retreating towards them from Vendôme.

At that point, Chanzy was still regarded as a General of talent, and he absorbed into his army from General Marivaux’s care all the units around Le Mans. Thus once again, Tissandier and his men found themselves part of the Army of the Loire.

The possibilities of balloon observation intrigued Chanzy, and Tissandier arranged a demonstration of its possibilities for the 22nd. The wind, which had been calm for three days, was now strong and gusty, causing the balloon to sway and thresh in a manner which looked terrifying to the onlookers, but which Albert Tissandier, in the basket, and familiar with such unpleasantness, endured with unperturbed calm. His stoicism greatly impressed the General and his staff.

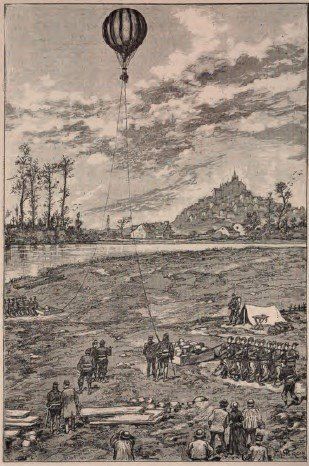

Tethered Ballon near the Sarthe River.

Note the rock-filled crates acting as anchors

for the pulleys through which the tether ropes pass.

Chanzy returned to headquarters, promising to employ the balloon as soon as he had formulated his moves against the Prussians. Tissandier’s delight is short lived, for the wind gets up, Ville de Langres rips open, and all’s to do again. Fortunately for the aeronauts’ reputation with Chanzy, he did not immediately call upon their services, and within two days the balloon was repaired and re-inflated. Yet strong wind and foggy days persisted, the Prussians seemed to be inactive, and Chanzy stood down the balloon, anticipating little activity in the immediate future.

All changed on 11 January. The Prussians launched a surprise attack on Chanzy’s forces disposed around Le Mans, but they failed to dislodge the French, and withdrew somewhat as night fell. Chanzy decided that the aeronauts could now earn their keep by ascending early the next day to ascertain the Prussian positions, and issued the order Tissandier and his fellow balloonists had been eagerly waiting for. But the Prussians were not waiting. Yet again they caught the French unawares, and by mid-day the Compagned’Aérostiers, still unblooded, joined the retreat from Le Mans.

During January, Chanzy rebuilt his army as best he could, planning to confront the Prussians in front of Laval. On the 27th Tissandier received orders to bring up the Compagne and position himself to provide observations on the left wing with three balloons. One of these would be the much- travelled Ville de Langres, which was inflated and ready to fly by the 29th. The weather was calm and bright, ideal for the several test ascents that were made. Indeed, some officers were taken up to impress upon them the balloon’s potential. All was ready ‘for the morrow’.

But the morrow brought news, not of Prussian manoeuvres, but of an armistice. Was it gossip? Was it real? The 30th was a turmoil of conflicting rumour and opinion unleavened by much fact. The aérostiers kept their hands in by making several ascents with the Ville de Langres, hoping the rumours were false, that French amour-propre was not to be trampled, and that – at last! – they would be able to prove themselves in action.

January 31st: the armistice is confirmed. There is nothing left for the aeronauts to do but mourn their defeat, deflate the Ville de Langres and pack it away, along with the only other one of the three to have been made ready, the George Sand. The work of the Aérostiers is over before it has truly begun and the Compagne dissolves even before any such official instructions reach it.

Its story has parallels with the earlier experiences of Civil War balloonists in the USA: barriers of official inertia are breached by civilian enthusiasts who by dint of personal drive and patriotism create a potentially valuable asset for their armies. The unhappy difference between the two histories is that the American aeronauts were able to prove their worth; the Compagne never had an opportunity to do so convincingly.

REFERENCES

Bacon, J.M.: The Dominion of the Air, 1902.

Cohn, E.M. “Pharmacists’ Balloon Mail During

1870 Siege of the Fortress of Metz”, Postal

History Journal, No.35, September 1973

[Provided to the author by courtesy of Akron

University, Ohio, USA]

Hildebrandt, A. (trans. W. H. Story): Airships Past & Present, London, Archibald Constable, 1908; notably Chapter XII: “The Development of Military Ballooning”, p.128ff.

Horne, Alistair: The Fall of Paris, Macmillan, London, 1965. (I have some reservations about Horne’s account, since his half-paragraph on American Civil War balloons is full of errors; while his reference to balloons at the siege of Metz credits Robinson with initiating the service and omits mention of the preceding ‘Military Pharmacists’’ balloons. It is thus legitimate to wonder whether his account of the Paris balloons is correct in every detail.)

Mead, P.: The Eye in the Air, HMSO, London, 1983

Narewska E. & E. Golding, Papillon de Metz: Resource of the month from the GNM Archive, September 2012, Guardian [Newspaper] Education Centre

Tissandier, Gaston: En ballon! Pendant le Siège de Paris, Dentu, Paris 1871

Wikipedia – “Siege of Paris” article

NOTES

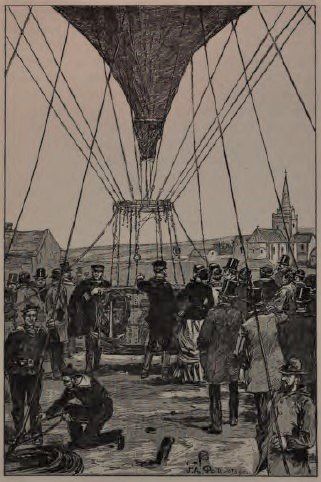

A crowd of onlookers watching launch preparations

for the "Ville de Langres" on 30 January 1871,

the day before the armistice

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org