The South African

The South African

Scapa Flow was the Royal Navy’s main base for the Grand Fleet during the two World Wars and the cornerstone of Britain’s maritime defence. It played an integral role in the Admiralty’s offensive strategy against Germany in the First World War and in the defence of the North Sea and the Atlantic convoys in the Second World War. It has been a protagonist in many dramatic events that took place in those seas in the past century.

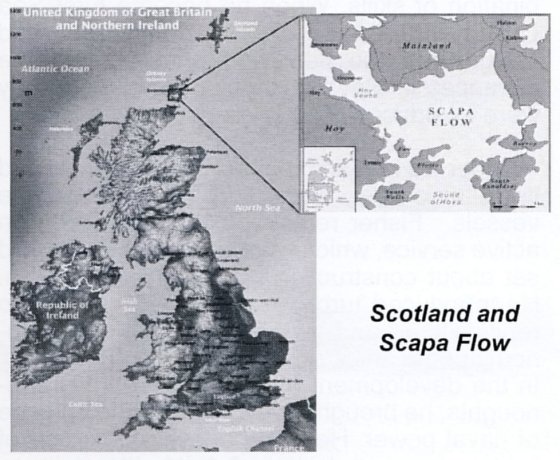

Scotland and Scapa Flow.

It is a windswept expanse of water some 12 miles across in the Orkney Islands, north of mainland Scotland. It is about 120 square miles in area and with an average depth of 30 to 40 metres and almost completely encircled by the islands of Orkney. It is one of the great natural anchorages of the world with easy access to both the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean. Warships have come and gone; countless vessels have come to grief there and its seabed is littered with the legacy of its maritime past.

For many centuries, Scapa Flow has been a safe and sheltered anchorage for ships and it was used as a harbour even in Viking times. Its name comes from the Old Norse Skalpaflói (meaning ‘bay of the long isthmus’), which refers to the thin strip of land between Scapa Bay and today’s location of the town of Kirkwall. The Viking expeditions to Orkney are recorded in detail in the eleventh century sagas, when they anchored there during their marauding expeditions.

It was not until the Napoleonic wars of the early 1800s that the British Admiralty first took an interest in Scapa Flow. Its location across from Skagerrak, the access to the Baltic between the 58° and 59° N latitude was ideal. At that time, the Admiralty needed a deepwater anchorage for trading ships waiting to cross the North Sea to the Baltic ports. Martello Towers were built at the accesses to the bay; their purpose was to defend these trading ships until a warship arrived to escort them to the Baltic Sea. Two of these towers can still be seen today.

In the early 1900s, the Admiralty once again looked at Scapa Flow, this time to be used as a base for the British Grand Fleet, to defend against a potentially new enemy in the north, Germany. Up until then, the conflicts it faced had been with France and Spain and against Russia in the Crimea, so there had been little need for a northern naval base. Germany had never been a traditional enemy. Before the unification of Germany in 1871, Britain was often allied in wartime with Prussia. The kings of Great Britain from 1714 with George I through to William IV were also rulers of the German state of Hanover, and even Queen Victoria, who reigned from 1837 until 1901, was more German than English. With her father’s early death, she had been brought up by her German mother, Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg. She married Albert, who was a German prince also of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha and six of their nine children married nobles of German descent.

It was in the generation that followed that two of her grandsons would become rulers in opposition: Wilhelm II, who had been crowned as German Kaiser and King of Prussia in June 1888, and George V, his first cousin, who became the King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India.

King George V

Kaiser Wilhelm

With England and Germany so strongly interrelated, any form of conflict between them seemed inconceivable. However, German rivalry soon became an important element and a potential threat to Britain’s interests, particularly in European waters. Wilhelm II started his reign with the intention of creating a maritime empire to rival the British and French empires, marking Germany as a truly global great power. Towards the end of the decade, as France, Russia and Italy began to modernise and expand their navies, she too became a competitor in the naval arms race.

Germany’s High Seas Fleet

In 1898, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz became the State Secretary for Imperial Germany’s Naval Office. Tirpitz was an ardent supporter of naval expansion and he viewed Great Britain, with its powerful Royal Navy as the primary threat to Germany’s development. He believed Germany could emerge victorious from a naval struggle with Britain, if initially, she followed a defensive strategy.

The Tirpitz premise was that any attacking fleet would require a 33% advantage in strength to achieve victory. Since the German Navy would be engaged in a defensive role in any war with the United Kingdom, he decided that a 2/3 ratio to the British fleet would be required ... and he went about building it. He oversaw the development of a concentrated and structured fleet to counter Britain’s obsolete and dispersed one. He built a fleet of superior and modern ships manned by well-trained officers and crews, with the opportunity to use mines and submarines to balance the numerical odds. Only then would he attempt a decisive battle against the British fleet, between Heligoland and the Thames. At the time, this premise was probably totally valid.

It is remarkable that during the initial period of German naval expansion, Britain did not feel particularly threatened. The Lords of the Admiralty felt that Germany was overextending herself and would be forced to reduce or entirely curtail this program.

Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

Sweeping reforms

It was Admiral John Fisher, who became the First Sea Lord and head of the Admiralty in 1904, who insisted that Britain’s probable enemy would be Germany. He stated that since Germany kept her whole fleet a few hours away, it was imperative for Britain to keep a fleet twice as powerful concentrated within a few hours of Germany. Admiral Fisher’s appointment was controversial, and he had to overcome a powerful conservative opposition to his ideas, but he was able to introduce sweeping reforms to help counter the growing threat posed by the expanding German fleet.

Admiral John ‘Jacky’ Fisher

He remains relatively unacclaimed, although certainly one of the great figures in British naval history. He had risen from the lowest to the highest rank in the Royal Navy. A fighting Admiral with extraordinary energy as well as administrative ability, he provided a rare combination of skills. When he became First Sea Lord in 1904, aged 63, he strengthened and reorganized the fleet and ensured that the advances in Naval technology and weaponry were introduced. This is his priceless legacy.

Under his leadership, the Royal Navy pruned its reserve fleet, discarding old and obsolete vessels. Fisher removed 150 ships, then on active service, which were no longer useful and set about constructing modern replacements. He introduced turbine engines and oil fuel to replace coal and thereby changed the autonomy of the ships and the logistic possibilities. In the development of the ‘all-big-gun’ Dreadnoughts, he brought a revolution in the balance of naval power. He also conceived the use of lighter armoured but fast battle-cruisers, essentially as scouts for the battlefleet and to lead it into action. Destroyers were brought in as a class of ship also intended for defence against attack from submarines. In addition to this, Fisher was an early proponent of the use of the torpedo, which he believed would supersede big guns for use against ships. He saw to the development of a submarine fleet, and the creation of the Royal Navy Air Service (later to be merged with the army’s Royal Flying Corps).

With regards to the fleet personnel, Fisher introduced the concept of structured and well- trained core crews of 40 per cent strength, only to be filled out to complement in time of war. This ensured better core training and, in particular, gunnery training, to improve the accuracy and rate of firing. He also ensured, perhaps more importantly in that period, that conditions were improved for the lower deck with merit beginning to displace privilege as grounds for promotion. He even introduced the daily baking of bread on all ships.

Fisher's reforms caused serious problems for Tirpitz's plans. The Germans could no longer depend on the superiority of the more modern and homogenised German squadrons over the heterogeneous British fleet or of a higher level of training of the German fleet.

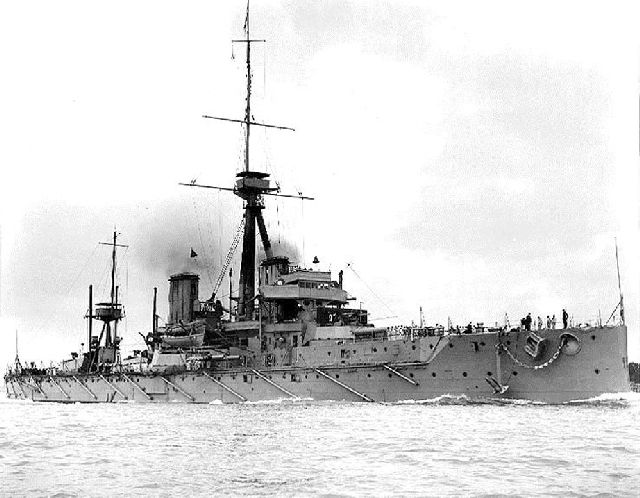

HMS Dreadnought

The most damaging blow to Tirpitz's plan came with the launch of HMS Dreadnought in 1906. The new battleship was the most heavily-armed ship in history. She had ten 12-inch guns, whereas the previous armaments were four 12-inch guns. The gun turrets were situated higher than usual and so facilitated more accurate long-distance fire. In addition to her 12-inch guns, the Dreadnought also had twenty-four 3-inch guns and five torpedo tubes below water. In the waterline section of her hull, the battleship was armoured by belt plates ranging in thickness from 4 to 11 inches.

HMS Dreadnought

The Dreadnought was the first major warship driven solely by steam turbines. Ships capable of battle with her had to be significantly larger than the old pre-dreadnoughts. This substantially increased their cost and necessitated expensive dredging of canals and harbours to accommodate them ... at a time when the German naval budget was already stretched thin.

Foreign Policy

There were also important diplomatic developments that allowed for a re-assembling and concentration of the British fleets. In 1904, Britain signed the entente cordiale with France, Britain's primary naval rival; resulting in France taking over a significant naval role in the Mediterranean. Their triple-alliance with Russia resulted in the subsequent alienation of the Ottoman Empire.

The destruction of two Russian fleets during the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 further strengthened Britain's position, as it removed the second of her two traditional naval rivals. Britain also negotiated an alliance with Japan and this again allowed her further withdrawal from the Eastern Seas, leading to a greater concentration of British battleships in the North Sea.

These alliances allowed Britain to discard the ‘Two Power standard’ first formulated in the Naval Defence Act of 1889, which required a British fleet larger than those of the next two largest naval powers combined. Thus, the focus shifted to solely out-building Germany and concentrating her fleet. In fact, at the start of war, Britain had launched a further five dreadnoughts with a further seven keels laid.

The Royal Navy's first strategic move, which happened in the month before war broke out, was the order to the Grand Fleet, handily mobilised in full for a royal review, to sail directly to Scapa Flow on 29 July 1914, its designated main base against Germany. The guardian of the nation, manned by 60 000 sailors, formed a grey steel line over 18 miles long as it steamed 800 miles up the east coast of the United Kingdom, taking over two days to arrive. The Grand Fleet was the ultimate guarantor of the traditional British naval strategy to blockade any European enemy, this time Germany.

The British Grand Fleet, in Scottish waters, barred the northerly route from Germany to the broad Atlantic; while the southerly route via the Channel was blocked by the destroyers of the Harwich Force and the Dover Patrol, supported by submarines and also by fifteen pre-dreadnoughts stationed along England's south coast.

The Grand Fleet sails for Scapa Flow

The German naval bases

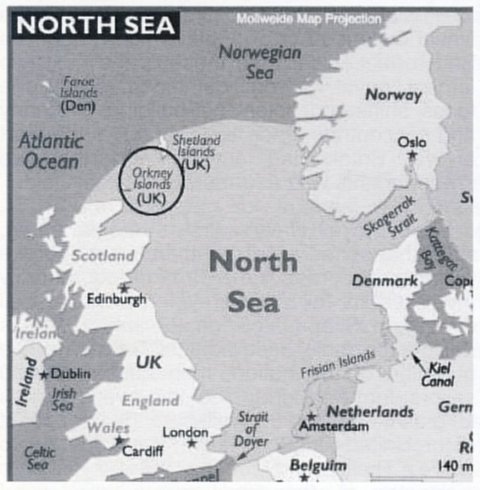

The primary base for the German High Seas Fleet in the North Sea was Wilhelmshaven on the western side of the Jade Bight. Another major base in the North Sea was the port of Cuxhaven, located on the mouth of the Elbe. In the Baltic, Kiel was the most important base and the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal through Schleswig- Holstein (opened in 1895) connected the Baltic and North Seas, allowing the German Navy to quickly shift naval forces between the two seas.

Map of the North Sea with Orkney Islands circled

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Scapa Flow was still unfortified, and Jellicoe, the Admiral of the Grand Fleet, started only in that year to have the base reinforced with minefields, artillery, and sunken block- ships. No German U-boats ever managed to enter Scapa Flow during the war, and only two attempts were made. The first, by U-18, took place in November 1914, but the sub was accidentally rammed by a trawler while it was trying to enter Scapa Flow, causing the submarine to flee and then sink. The second attack, by UB-116, in October 1918, encountered the sophisticated defences then in place. It was detected by hydrophones and then destroyed by shore-triggered mines before it could enter the anchorage.

The strategy of the German navy was to break the British blockade and to allow German mercantile shipping to operate. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy was attempting to engage and destroy the German Fleet, or keep the German force contained and away from Britain's own shipping lanes.

There were two important naval battles launched by the British from Scapa Flow during the first six months of the war. The first was the Battle of Heligoland Bight, just after the outbreak of war, fought on 28 August 1914, that very successfully ambushed German patrols off Germany’s northwest coast. The second, the Battle of Dogger Bank on 24 January 1915, was in response to a series of sorties by the fast German battlecruisers of their Scouting Group to raid the British coast, as the bait for the Royal Navy. The British surprised the attacking force, but this time a signalling mix- up caused the British ships to break off pursuit when close to success, with ultimately equal losses on both sides.

These operations culminated in the Battle of Jutland, in the North Sea near Denmark from 30 May to 1 June 1916, when the German High Seas Fleet confronted the whole of the Grand Fleet. It was the largest naval battle and the only ‘full-scale’ clash of battleships in the war. There were 151 British warships involved against 99 German warships.

The battle was inconclusive although the outnumbered German fleet managed to return to base after inflicting greater damage than it had received. British losses were fourteen ships: six cruisers and eight destroyers with 7 000 killed or wounded against Germany’s loss of eleven ships: a pre-dreadnought, five cruisers and five torpedo boats, with 3 000 killed or wounded.

Both sides called it a victory, but the British certainly won strategically, convincing Admiral Scheer, the German naval commander, that even a favourable outcome of a fleet action would not secure German victory in the war. Scheer and other leading admirals therefore advised the Kaiser to order a resumption of the unrestricted submarine warfare campaign.

On 5 June 1916, just four days after the Battle of Jutland, the Minister of War, Lord Kitchener, visited the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow on his way to Russia for a goodwill visit. He never reached Russia. Kitchener lost his life when his ship, the cruiser HMS Hampshire, struck a mine after leaving Scapa Flow and sank in heavy seas just off the north-west coast of Orkney. Of the 667 men on board there were only 12 survivors. A greater loss of life would be suffered the following year when the battleship HMS Vanguard exploded at anchor in Scapa Flow with the loss of 843 men; only two of those on board survived.

The scuttling of the German Fleet in Scapa Flow

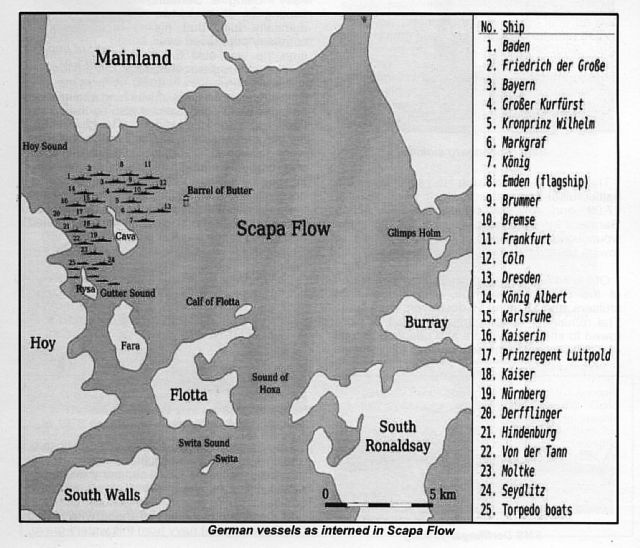

The signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918 at Compiègne, France, effectively ended the First World War. The Allied powers agreed that Germany's U-boat fleet should be surrendered without the possibility of return, but they were unable to agree about the fate of the German surface fleet, so it was resolved that the ships be interned at Scapa Flow with a skeleton crew of German sailors until a final decision had been reached.

A total of 74 ships of the German High Seas Fleet arrived in Scapa Flow for internment. The French and Italians each wanted to keep a quarter of the ships, but the British wanted them to be destroyed. Negotiations over the fate of the ships dragged on for seven months at the Conference. Admirals Beatty and Madden were concerned that scuttling could be attempted and had proposed plans to seize the German ships and intern the crews ashore, but their suggestions were not taken up.

Rear Admiral von Reuter

Fearing that the Royal Navy would take over his ships in the event of a breakdown of the talks, Rear Admiral von Reuter, the Commanding Officer of the interned fleet, had arranged with his officers the possibility of scuttling the ships. German crews had spent the idle months preparing for the order, welding bulkhead doors open, laying charges in vulnerable parts of the ships, and quietly dropping important keys and tools overboard so that valves could not be shut.

When, on the morning of 21 June 1919, the British First Battle Squadron and its escorting destroyers left Scapa Flow on an exercise at around 10.00, Admiral von Reuter gave the command to scuttle the entire fleet in the Flow.

Only one British destroyer remained on duty there. Two others were undergoing repairs; there were also a few drifters and trawlers and one depot ship.

Scuttling began and there was no noticeable effect until noon, when some ships began to list heavily, and all the ships hoisted the Imperial German Ensign at their mainmasts. The Commander of the Battle Squadron, Admiral Freemantle, started receiving news of the scuttling at 12.20 and cancelled his squadron's exercise, steaming at full speed back to Scapa Flow. He had radioed ahead to order all available craft to prevent the German ships sinking or to beach them.

Admiral Freemantle and a division of ships arrived at 14.30 in time to see only the large ships still afloat.

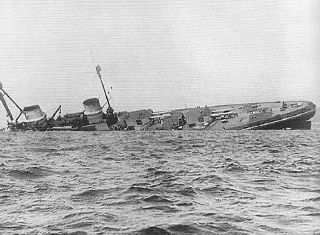

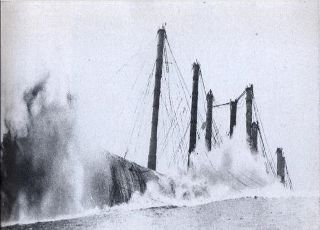

SMS Hindenburg sinking

The last German ship to sink was the battlecruiser Hindenburg, which went down at 17.00, and only the Baden survived. Nine Germans were shot and killed and about sixteen wounded while resisting the boarding parties, or rowing towards land aboard their lifeboats.

SMS Derfflinger sinking

Of the 74 German ships in Scapa Flow, fifteen of the sixteen battleships, five of the eight cruisers, and 32 of the 50 destroyers were sunk. The remainder either remained afloat or were towed to shallower waters and beached. A total of 52 ships went to the seafloor and this remains the greatest loss of shipping ever recorded in a single day. Most were initially left at the bottom of Scapa Flow, the cost of salvaging them being deemed to be not worth the potential returns, owing to the glut of scrap metal left after the end of the war.

The raising of the ships

A salvage company, formed in 1923, raised four of the sunken destroyers and, at about this time, an adventurous entrepreneur named Ernest Cox bought 26 sunken destroyers from the Admiralty for £250 each, as well as the battleships Seydlitz and Hindenburg.

In a later contract, Cox also acquired the battleships Moltke, von der Tann and two battle cruisers.

Cox became known throughout Scotland as the ‘man who bought a navy’. Using a German floating dry dock and two admiralty tugs that his company purchased over time, he was able to lift and beach his destroyers.

Cover of book about Cox

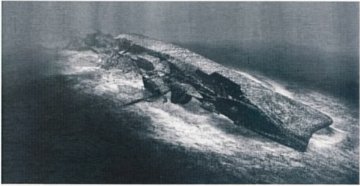

Various techniques of winching and inflated balloons were used, helped also by the spring tides that rose and fell from 10 to 12 feet. For the larger vessels other salvage techniques were developed. Divers would patch the holes and create watertight sections in the submerged hulls and fit cleated trunk airlocks for access. Then with compressed air pumped into them they would attempt to make the hull rise to the surface. The ship could then be floated and towed to the breaker shipyards.

SMS Kaiserin resurfaces

These methods were costly and complicated, and they faced many technical and financial problems. However, Cox's company eventually raised 24 destroyers, two cruisers and five battleships. It is a story of ingenuity, courage, and the resourcefulness of those who raised the Kaiser’s great navy from this watery grave.

The remaining seven wrecks – three battleships and four light cruisers – lie in deeper waters and, although they were never raised, they have been substantially salvaged over the years, with armour plate blasted away and non-ferrous metals removed. They remain, however, extremely impressive underwater wrecks, not least because of their sheer, awesome size.

Scapa Flow and the Second World War

Because of its strategic position in the

North Sea and its distance from German

airfields, Scapa Flow was again selected as

the main British naval base during the Second

World War (1939-1945). Its primary role was

to bar the northerly route to the broad Atlantic,

North and Barents seas

... and therein lies another fascinating

history of this famous naval base.

References

Clay, Catrine, King, Kaiser, Tsar: Three Royal

Cousins and the Lead-up to War (John Murray, 2015).

DiverNet, ‘Scapa Flow in 3D’, archived from

the original on 6 June 2011.

George, S C, Jutland to Junkyard: The raising

of the scuttled German High Seas Fleet from

Scapa Flow. The greatest salvage operation

of all time (Patrick Stephens Ltd, 1973).

Kennedy, Paul, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914 (Allen &

Unwin, 1980).

Miller, James, The North Atlantic Front:

Orkney, Shetland, Faroe and Iceland at War

(Birlinn Ltd, 2004).

Padfield, Peter, The Great Naval Race: Anglo-German Naval Rivalry 1900-1914

(Birlinn Ltd, 2005).

Springer, Will, Scapa Flow: Graveyard of the German Fleet.

Wikipedia, ‘Germany – United Kingdom

Relations’ and ‘The Imperial German Navy’.

Woodward, David, ‘Admiral Tirpitz, Secretary

of State for the Navy, 1897-1916’ in History Today, Vol 13, Issue 8, August 1963.

Wrecks designated as military remains (Maritime and Coastguard Agency, December

2006)

SMS Brummer still lies on the seabed

The Dunning landing

On 2 August 1917, a South African born squadron commander, Edwin Harris Dunning, DSC, RNAS, made naval history by being the first pilot to land an aeroplane (a Sopwith Pup) on a moving battleship, the HMS Furious in Scapa Flow. This success was short-lived, however, because only five days later he was killed during his second landing attempt of that day, when an updraft caught his port wing, throwing his aircraft overboard. Knocked unconscious, he drowned while in the cockpit. Nonetheless, his historic landing launched the development of flat decked aircraft carriers.

Cmdr E H Dunning and his Sopwith Pup

after landing on HMS Furious

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org