The South African

The South African

Preamble

This article is a continuation of the author’s earlier article titled ‘The 175th anniversary of Durban’s Battle of Congella’ which appeared in the Military History Journal, Volume 18, No 1, December 2017, pp38-41).

Introduction

In Durban’s famous Battle of Congella, which took place on 23/24 May 1842, the Afrikaner Boers of the Republiek van Natal defeated the resident British troops from the well-established Cape Colony. At that time, the Governor of the Cape Colony viewed the so-called Republiek van Natal as the District of Natal, within the Settlement of the Cape of Good Hope and subject to Cape Colony rule.

The defeated British troops, under Captain Thomas Charlton Smith (1794–1883), were forced to retreat to Fort Port Natal (nowadays known as the Old Fort, Durban) where he and his men were promptly besieged by the Boers. It was here that Durban took root.

Military prowess was of paramount importance to the Boers (Saunders, 1992, p116). The Boers, under the command of Commandant-General Andries W Pretorius (1798–1853), had its hoofkwartier (headquarters) at the nearby laager camp of ‘Kongela’ (Congella). A sketch of Cmdt-Gen Pretorius’ Voortekker camp at Congella is reflected below.

A view of Cmdt Gen Andries Pretorius’ Voortrekker camp at Congella in 1842.

(Source: M Adulphe Delagorgue, 1847, Voyage dans L’Afrique Australe,

Local History Museums’ Collection, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal).

Dick King’s heroic 970-kilometre horseback ride from Port Natal to Grahamstown saw the summoning of relief for the besieged British garrison at Fort Port Natal. On 24 June 1842, the first reinforcements arrived in the Bay of Natal (Durban) from Algoa Bay (Port Elizabeth) aboard the schooner Conch. These British troop reinforcements were in time to save Capt Smith’s garrison from imminent surrender or starvation.

On the next day, 25 June, the British frigate HMS Southampton, under the command of Capt Josias Ogle, anchored outside the sandbar at the entrance to the Bay of Natal. She drew too much water to cross the sand bar, but she had 50 cannon onboard and five companies of the 25th Regiment of Foot (King’s Own Borderers) under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Abraham Josias Cloete. The Boers realised they were powerless to stop the British troops landing, so they hastily retreated to Congella, where they and the other Boers gathered their belongings before abandoning their settlement. Russell (1911, p190) notes it was ‘… reported that Congella was being deserted by the Dutch farmers’.

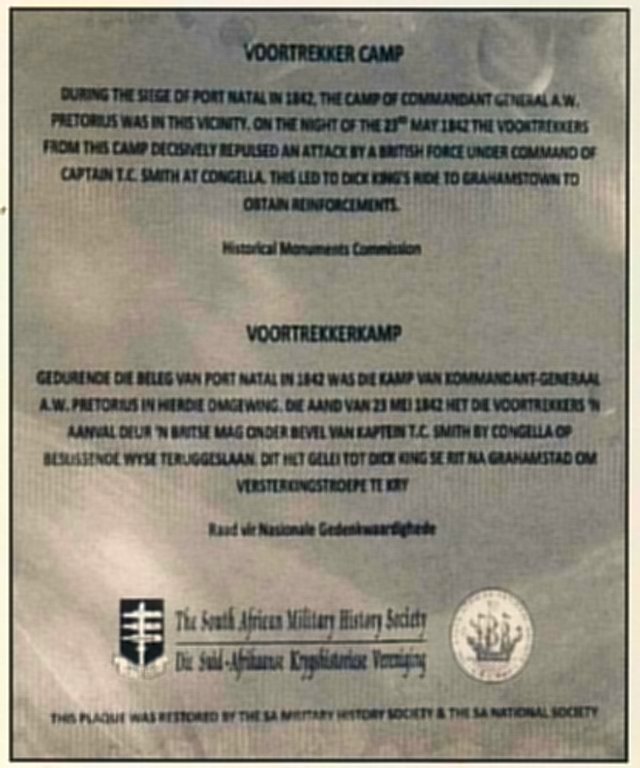

A (present-day) restored plaque by the South African Military History Society can be seen in Congella Park, Umbilo. The English text appearing on this plaque states:

VOORTREKKER CAMP

DURING THE SIEGE OF PORT NATAL IN 1842,

THE CAMP OF COMMANDANT GENERAL A W

PRETORIUS WAS IN THIS VICINITY. ON THE

NIGHT OF THE 23RD MAY 1842 THE

VOORTREKKERS FROM THIS CAMP

DECISIVELY REPULSED AN ATTACK BY A

BRITISH GARRISON FORCE UNDER

COMMAND OF CAPTAIN T C SMITH AT

CONGELLA. THIS LED TO DICK KING’S RIDE

TO GRAHAMSTOWN TO OBTAIN

REINFORCEMENTS.

Cmdt-Gen Pretorius and the 300 to 400 Boers under

his command made their way some nine miles

(15 kilometres) to Steilhoogte (Cowies Hill) and set

up camp on the farm Salt River, where

William Cowie lived. According to a biography of

Cmdt-Gen Pretorius by B J Liebenberg (1977,

p179), on 3 July 1842 Pretorius broke up his

camp in Cowie’s Hill (as originally spelt) and

headed in the direction of Pietermaritzburg,

home of the Boer Volksraad.

Cowies Hill is the name of a wooded suburb

familiar to many Durbanites, but what is the

military history behind this early pioneer,

William Cowie, and what was his role, if any,

during and after the Battle of Congella and the

setting up of the Boer camp at the farm Salt

River? Answering this question is the objective

of this article.

As a starting point to finding the answers,

the author contacted the Department of Arts

and Culture, the KwaZulu-Natal Archives and

the Records Service, Pietermaritzburg Archives

Repository, enquiring about Steilhoogte or

Cowies Hill. The Head of Department for

Repository Management advised that an

electronic search for keywords ‘… Steilhoogte,

Cowies Hill, Cmdt Gen Pretorius and 400 Boers

using the NAAIRS database’ was undertaken,

but that neither photographs nor articles were

available in the collection. The author then

approached other sources for information,

including Hazel L England (retired

museum curatrix from the Pinetown Museum),

the Killie Campbell Collections and the Old

Court House Museum, Durban. The documents and

images received from each of these sources helped

to craft the article, though, sadly, no image of William

Cowie could be found.

Background

After the British had taken over the Cape Colony

from the Dutch in 1806, they did everything in their

power to ensure that the Boers became subjects

loyal to the British Crown. The term Boer is Dutch

for ‘farmer’ and the Boers are descendants of the

predominantly Dutch migratory farmers or

‘trekboers’. After some 30 years of conflict, many

of the Boers were dissatisfied with their life under

British rule and left the Cape Colony. Since there

was a general state of discontent, the Boers

travelled north in order to find their own homeland.

The Boers left the Cape Colony to escape what they

regarded as the unacceptable controls of the Cape

administration (Duminy and Guest, 1989, p126).

They became known as ‘Voortrekkers’. From 1824

some Cape Colonists had also filtered into Natal for

purposes of trade and/or settlement. In December

1837 a large group of Voortrekkers crossed the

Drakensberg into what they called the ‘Republiek

van Natal’. Pieter Mauritz Retief was their leader.

The early life of William Cowie

From British Settlers’ research undertaken by

Shelagh O Spencer (1989, p6), one finds that

William Cowie was born circa 1809 in Scotland. His

origins are not known. While he was undoubtedly

British, he was an exception among the

Voortrekkers since he had married into a Boer

family. His wife was Magdalena Josina Laas, the

daughter of Andries Marthinus Laas and Sara

Salemina Vermaak (Krüger, 1977, p178).

Plaque commemorating the site of the Voortrekker Camp.

Andries Marthinus Laas had accompanied

Voortrekker Jacobus Johannes (‘JJ’) Uys and his

son Pieter from the Cape Colony to Natal in 1837.

William Cowie should not be confused with

another British Settler with a similar (but not

identical) surname – William Cowey. William Cowey

(born circa 1815, died 29 October 1886 in Durban)

arrived in Natal on the Minerva. William Cowey, his

wife (Mary Ann Goulden), and his wife’s relatives

came to Natal under arrangement with W

J Irons’ Christian Emigration and Colonization

Society. The Coweys’ farming land was in the

Verulam District.

During April 1838, William Cowie was one of a

commission of six sent by Commandant-General

Carel P Landman of the Boers’ United

Laagers (who were camping below the Drakensberg),

to assess the feelings of the British at the

Bay of Port Natal on the Boers settling in Natal.

According to Shelagh Spencer, on ‘…arrival at the

Bay four days later, the commission found that the

few English inhabitants lacked protection for

themselves and their property, were not in a

position to defend their settlement, and were

favourable towards the advent of the Boers’.

Cmdt-Gen Landman then proceeded to annex

the Bay of Port Natal and surrounding land in the

name of the United Laagers. William Cowie was

appointed field cornet (veldt kornet, one who had

similar functions to a Justice of the Peace) with the

authority to provide whatever protection was

necessary to the inhabitants. Cowie was sympathetic

towards his neighbours who were British

traders and to Boer settlers around the Bay of Port

Natal.

The Battle of Blood River — known in Afrikaans

as the ‘Slag van Bloedrivier’ and in isiZulu as

‘iMpi yaseNcome’ — took place on 16 December

1838 between a group of 464 Voortrekkers led

by Andries Pretorius and up to 20 000 warriors of

the Zulu Army on the bank of the Ncome River. The

Voortrekkers won the day and, soon after,

William Cowie rode northwards to the Zulu country

to receive, from Zulu King Dingane, the first

instalment of 1 300 cattle, 400 sheep, 43 saddles

and 52 guns he had promised as reparations for a

peace settlement. It was Cowie’s difficult task to

explain that his visit to King Dingane was not to

conclude peace with the Zulus but merely to receive

reparations from the Battle of Blood River. Cmdt-

Gen Pretorius divided the 1 300 cattle received

among the 334 men in his laager. William Cowie

received only two head of cattle. He was furious to

receive such a paltry number and duly returned

them.

The Boer Republiek van Natalia

Natalia (the District of Natal) was divided into twelve

wards with two representatives from each ward.

During this Boer government period (from 1838 until

12 May 1843, when Natal was declared to be a

British Colony), Pieter Mauritz Burg (nowadays

Pietermaritzburg) served as its capital. A Volksraad

with 24 members was elected in March 1839.

William Cowie’s loyalty to the Boers was tested

when conflict arose between the Boers and the

British. Engelsman Cowie soon lost favour with the

ruling coterie when, on 4 January 1840, Pretorius

was ordered by the Volksraad to take, by force, 40

000 cattle from King Dingane. William Cowie aired

‘his opinions too freely’ on the eve of this

‘Cattle Commando’ and was soon suspended from

his office of Field Cornet. There was strong

suspicion that he was conveying adverse criticism

of the Voortrekkers to the Cape Colony Press (and

indirectly to the Governor of the Cape Colony).

By early 1842, the Cowies were residing on part

of the farm Salt River, or Salt River Poort

(5 967 acres) which belonged to his father-in-law,

Andries Marthinus Laas. According to one report,

the Cowies’ residence on this part of Salt River was

at a nearby promontory (a prominent mass of land

overlooking or projecting into a lowland) called

Buffalo Kop. This hill was probably known by the

Boers as Steilhoogte [the] and home of William Cowie

as ‘Cowies Place’.

The Siege and Relief of Port Natal

With the arrival of Capt Thomas Smith at Port Natal

in 1842 to take charge of British troops, this placed

William Cowie in an invidious position – he was

persona non grata with both the British and the

Boers. Within a few days of Smith’s arrival, Cowie

was subjected to cross-examination by the Boers

with the object of pinpointing the whereabouts of

the redcoats ('rooibatjes' as the Boers termed the

27th Inniskilling Regiment of Foot, soldiers under

Smith’s command). However, William Cowie was

uncooperative about British military plans, which he

refused to divulge. A body search of Cowie would

have revealed confidential letters from the British

forces’ commander, but fortunately these were not

discovered by his interrogators.

During the siege of Fort Port Natal, Cowie and

a ‘little band’ of men continued to creep into the

camp at the dead of night to see whether they could

render any assistance (in the form of smuggling

food supplies) to Capt Smith and his men. Cowie

spent much time immersed in the unguarded

swamp water and the ‘almost impenetrable furze’

near Fort Port Natal. Cowie and his band’s heroic

actions (on several occasions), brought much relief

to the beleaguered redcoat garrison during this

siege period. The Times newspaper,

Pietermaritzburg, dated 7 January 1857, reports it

as ‘… the fatal period when fortune frowned upon

the British Powers, this little band were (sic) the

instruments through whom the salvation of the

Troops and the retention of the British Authority was

affected’. This newspaper article further states that

William Cowie ‘… jeopardised his life to serve his

Queen and did more than any other man at the

time’.

William Cowie goes into hiding

Later the Boers discovered that it was William

Cowie who had conveyed information of a military

nature to the British garrison at Fort Port Natal. This

resulted in Cowie being hunted for capture and trial

by the Boers. For the next few days and nights,

Cowie resorted to hiding and moving frequently on

his hill. According to a Natal Star newspaper report

dated 12 November 1856, the Boers ‘… hunted him

like a dog. For days and nights, he hid himself in

and about the hill beating (sic) his name’. The report

continues that, on one occasion, the Boer hunters

came across his house just as he had crept inside

for food. He had only time to step into his bedroom,

sit down on his bed with his gun besides him with

‘… a determination to sell his life dearly’. However,

his wife, Magdalena, succeeded in distracting the

Boer party with coffee and other refreshments –

thereby throwing them off the scent of her ‘hunted’

husband.

From his hiding place at Cowies Hill, William

Cowie is reputed to have witnessed the frigate

HMS Southampton, under full sail, coming up the

Natal coast and bringing relief to the siege of Fort

Port Natal. William Cowie was there to take part in

the welcome. He is considered an unsung hero of

the Battle of Congella (and victory for the British)

as it was Cowie who kept the surrounded garrison

informed regarding the movement of Boer patrols.

As Cowies Hill was on the direct road from Durban

to Pietermaritzburg and a frequent stopping place

for travellers, there would have been little

information which would not reach William Cowie’s

ears. Nowadays the eponymous hill with its leafy

Old Main Road (renamed Josiah Gumede Road) is

a major feature in the Comrades Marathon held

annually between Durban and Pietermaritzburg. In

the ‘down run’ (Pietermaritzburg to Durban), the

Cowies Hill section of the route is where the battle

is often lost (or won). Many a runner has

succumbed to the lure of the downhill, failing to

remember that the finishing line remains another

15 km away!

The eastern part of Salt River farm at Steilhoogte

faced what is today Westville and the Bay (of Natal)

which was an ideal site for Boer defensive positions,

including their trenches. The Boers also feared the

Zulu impi turning upon them (Russell, 1899, pp51-52).

So, the retreating Boers camped at Steilhoogte

during the period 28 June to 3 July 1842, whereafter

they made their way to Pieter Mauritz Burg.

According to Hazel England, there ‘… are no maps

or drawings of the retreat of the Boer men to

“Cowie’s Place”. They did not stay long as the

English soldiers were not far behind’. Her notes

indicate evidence that the retreating ‘… Boers’ fears

were verified by a visit from Mr Dennis Charlton,

son of the first Pinetown chemist, when in 1994 he

visited the Pinetown Museum’. She adds that both

‘Dennis and his elder brother Hugh recalled playing

in the Boer trenches in the late 1920s’.

Once in Pieter Mauritz Burg, discussions ensued

with the Boer leaders and the Volksraad as to their

submission to the Queen’s authority. On 11 July

1842, a delegation from the Volksraad met Lt

Col Abraham Josias of the 25th Regiment of Foot

on Steilhoogte near the home of William Cowie to

discuss peace negotiations between the parties

(Preller, 1937, p267). It is evident that the Steilhoogte

farm with its Cowie’s Hill, played a

significant historical role after the siege at Fort Port

Natal had been raised. Following these discussions

on the farm, the Boer deputation then signed a

Treaty of Surrender in Pieter Mauritz Burg submitting

to British Authority in Natal (Volksraadnotule

Natal: Appendix 14/1842, pp418-9).

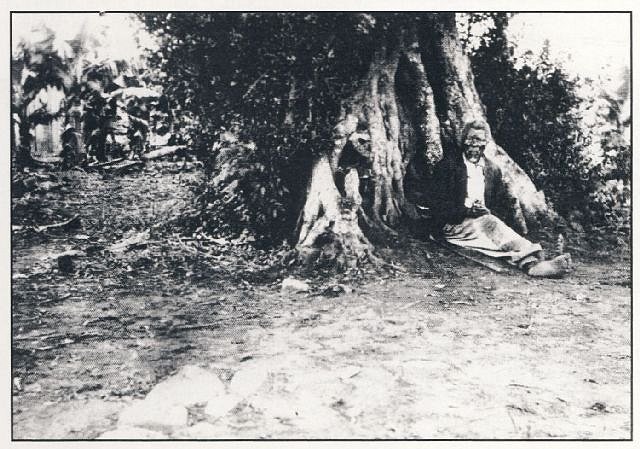

Amnesty Tree, Cowies Hill

From Hazel England’s records, behind William

Cowie’s house on the farm, was a tree. This large

old ‘Voortrekker’ was reputed to be the site of the

Cowie house where the peace negotiations had

been conducted. The tree had grown through the

wall of Cowie’s house and became known as the

Indaba Tree. Construction to widen Ernest Whitcutt

Road during the 1960s, led to the destruction of this

historic old tree reputed ‘… to have a span of

100 foot and a trunk more than 12 foot in diameter’

(Annals of Pinetown, 1968). Interestingly, the

author’s sister, pharmacist Ines G C Drake, and her

family, used to reside at a house known as

West Winds, Old Main Road – less than a kilometre

from the site where this (reputed) historic tree once

stood.

During the 1920s Ernest Whitcutt had bought

large tracts of land in the Cowies Hill area and built

a house (known as Woodside) on Old Main Road.

Upon his death, the property and house were

inherited by his daughter, Thelma McDonald, who

resided there until her death. If this Indaba Tree

was already fully grown around 1842 (year of the

Battle of Congella), nowadays the tree would have

been more than 200 years old.

There is an image of the

Amnesty Tree, Cowies Hill. According to Hazel

England, the photograph was taken in the early

1900s. The image was donated to the Pinetown

Museum by Thelma McDonald. In researching

historical text for this article, the author paged

through an old photograph album in the

Killie Campbell Collections. There is an identical

photograph of the Pinetown Museum’s image but

with the following legend typed beneath it:

‘THIS IS AN ENTRY IN MY DIARY FRIDAY FEB.

9th, 1934. A.H. Smith

Amnesty Tree, Cowies Hill.

On 15 July 1842 the ‘Republiek van Natal’

formally submitted to British rule. Although the

Boer Volksraad remained in existence until 1845,

from 1843 the territory was under the effective

control of the British Representative, Henry Cloete.

Many Boers refused to swear allegiance to the

British Crown and retreated instead towards the

Drakensberg to pastures new, thereby eluding the

British dominions. After all, the main reason for the

Boers originally leaving the Cape Colony (the Great

Trek) had been that they refused to accept British

rule and were unwilling to comply with British law.

As Brookes and Webb note (1965, pp29-30), the

In May 1843, a Proclamation was published at

the Cape Colony announcing the recognition of the

district of Port Natal as British territory (Bird, cited

in Brookes and Webb, 1965, p48). The question of

land titles was complicated and vexatious. The

Volksraad had granted land on a lavish scale but

no survey had been possible (p50). Now, under

British Colonial rule, all land within the District of

Natal was (British) Crown Land. Each adult male

Boer was limited to enjoy only one farm where he

resided, and he was required to repurchase that

one farm from the British Colonial Administration.

While the land that the Boers occupied was protected,

their Eigendoms Grondbrief, or title deed,

was not. This meant that the Colonial Administration

would only issue a title deed based on a surveyed

diagram of a farm that had been occupied for at

least twelve months. On 17 February 1845,

Dr William Stanger was appointed the first

Surveyor-General of Natal (Russell, 1911, p159).

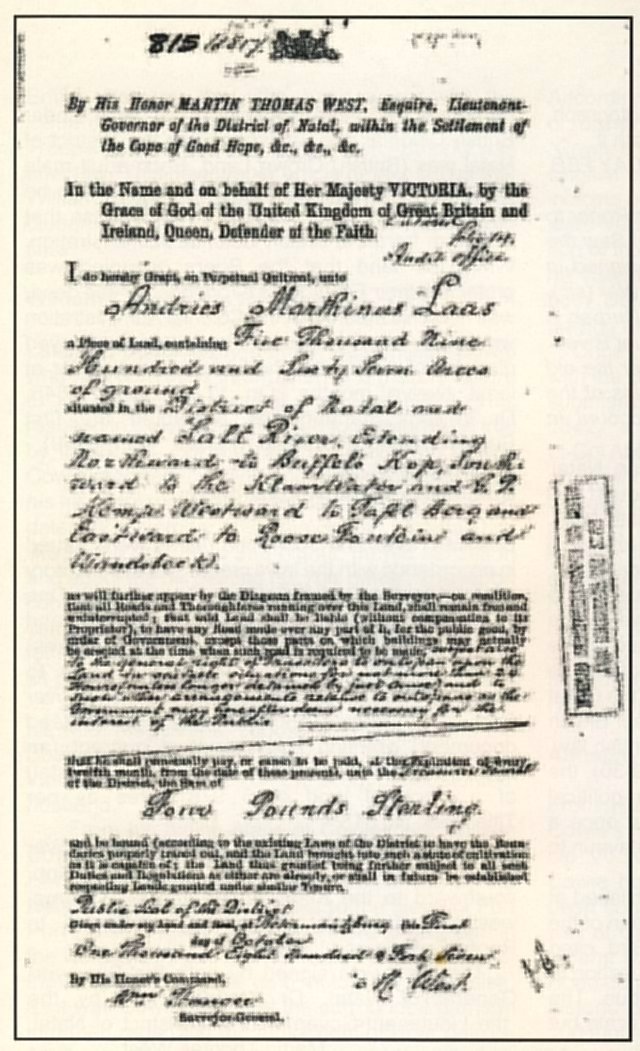

Colonial Government title deeds

Between 1846 and 1864, title deeds were issued

in accordance with the laws created for the Territory

of Natal by the British Colonial Government. One

of the first title deeds issued in August 1847 (and

surveyed by Government Surveyor Thomas Okes)

by the British Colonial Administration was to

Andries Marthinus Laas of Salt River (or Salt River

Port – both names appearing on the title deed

document) granting him perpetual quitrent (an

annual payment to the Treasurer-General of Natal)

of a piece of land of 5 976 acres per

Title Deed No 815.

Title Deed 815.

Inspection of this title deed shows that Salt River

farm extended ‘… northward to Buffalo Kop,

southward to the Klaar Water and G P Kemp,

westward to Tafel Berg and eastward to

Roose Fontein and Wandsbeck’.

The deed was signed by both the Surveyor-

General of Natal, Dr Stanger and the Lieutenant-

Governor of the District of Natal, Martin Thomas West.

Since farms were not

being granted freehold to the

Boers (and to other farmers),

the British had thereby

wrested the land of Natal

from the Boers. The British

Colonial Administration only

issued new title deeds to

those who could prove

occupancy. The title deeds

which were issued (and the

succession thereof), remain

in force today in KwaZulu-

Natal.

Conclusion

The enquiry into the role of

William Cowie during and after the Battle of Congella

and the Boer camp on the Salt River farm provides

a fascinating glimpse of the military history of early

Cowies Hill. His health had been indifferent for

several years. According to Shelagh Spencer, the

first indication of this dates to March 1853;

according to his obituary, he had long suffered from

an organic disease of the heart and, during his last

visit to the Zulu country, for elephant hunting, he

had contracted fever from which he had never fully

recovered.

Despite his role, William Cowie was accorded

no recognition for his bravery during the Siege of

Port Natal and died in relative obscurity on 23

October 1856 at his farm Umgeni in the Umvoti

District. This was some three years after the death

of Cmdt Gen Andries Pretorius. William

Cowie was still relatively young – under

50 years of age. While his pioneering and

historic role in early Natal military history

may be forgotten, for more than 177 years

Cowie’s surname, at least, has served as

his legacy in KwaZulu-Natal.

Bibliography

Brookes, E H, and Webb, C de B, A

History of Natal (Pietermaritzburg,

University of Natal Press, 1965).

Duminy, A, and Guest, B (eds), Natal and

Zululand. From Earliest Times to 1910. A

new history (Pietermaritzburg, University

of Natal Press, 1989).

Krüger, D W, Dictionary of South African

Biography, Volume III (Goodwood,

Tafelberg Uitgewers, 1977).

Liebenberg, B J, Andries Pretorius in

Natal (Cape Town, H&R Academica,

1977).

Preller, G S, Andries Pretorius Lewensbeskrywing

van die Voortrekker Kommandant-Generaal (Johannesburg,

Afrikaanse Pers Beperk, 1937).

Russell, G, The History of Old Durban and

Reminiscences of an Emigrant of 1850

(Durban: P Davis & Sons, 1899).

Russell, R, Natal. The Land and its Story

(Pietermaritzburg, P Davis & Sons, 1911).

Saunders, C (ed), Illustrated History of

South Africa. The Real Story (Reader’s Digest

Association, South Africa [Pty] Ltd, 1992).

Spencer, S O, British Settlers in Natal 1824-1857.

A Biographical Register. Volume 5

(Pietermaritzburg, University of Natal Press, 1989).

Acknowledgements

A significantly compacted earlier version of this

article appeared in The Mercury newspaper,

Durban, on 5 August 2019. Gratitude is expressed

to septuagenarians Adrian Mathison Rowe and

Hazel England who gave their respective

constructive input to earlier drafts of this article.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's

Home page

(Source: Udo Averweg Collection).

A delightful day. Went with Mr Smith & Mr Roper to

Woodside Estate (Mr E. Whitcutt’s Place) Saw the

old home where the peace treaty was signed in

1845 (sic) …. at the end of the Congella War (sic),

on the oldest part of the Road between Durban &

Maritsburg, (sic) on the bank of the Palmiet River.

Took snap of old Native, M’liko, 98, under the old

tree, which has grown up among the ruins of the

old house. Wrote Mr Smith a long account in

evening.’

(Source: Local History Museums’ Collection,

Pinetown, after the Battle of Congella

KwaZulu-Natal, Pinetown Museum No 24/11554).

‘… Great Trek was in its essence a political

movement, organised and purposeful, at once a

protest against British rule and an endeavour to

escape from it.’

(Source: Office of the Registrar of Deeds,

Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal).Annals of Pinetown. Compiled by the

Pinetown Women’s Institute (1968).

South African

Military History Society /

scribe@samilitaryhistory.org