The South African

The South African

All photographs by courtesy, Deutsches U Boot Museum,

Cuxhaven-Altenbruch, Germany, http://dubm.de.en

Introduction

Coinciding with the beginning of the fourth year of the Second World War (1939-1945), the U-Boat (submarine) Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Karl Dönitz, met with Hitler on 26 August 1942 and again on 28 September 1942. Dönitz began his presentation to Hitler by explaining that having U-boats fighting off the American coast was no longer sufficiently profitable, mainly owing to the effectiveness of ASW (anti-submarine warfare) measures, especially United States’ air patrols and the extension of the convoy network. Dönitz stressed two extreme difficulties his boats faced attacking convoys in the North Atlantic: Growing numbers of radar-equipped long- range Allied aircraft able to provide air cover nearly all the way across the North Atlantic, and the likelihood that the tonnage sunk of Allied vessels was certain to decline. To reverse this decline, a new U-Boat arm urgently needed, firstly, a long-range high performance bomber to seek out convoys and to warn of an approaching Allied air thrust and, secondly, a new attack submarine with a very high submerged speed to outmanoeuvre and outrun escorts during attack and withdrawal phases. Hitler was not in favour of the new aircraft, but strongly endorsed the construction of new U-boats with high underwater speed.

Dönitz, in his Memoirs, stated: ‘It was on the sudden onslaught in the waters off Cape Town that the U-boat command pinned its high hopes. To reach the area, the U-boats would have to travel nearly 9 600 km, and for Type IXC boats such an operation would only be possible provided that a submarine tanker was made available en route to replenish their supplies of fuel. Even so, it was an operation which seemed to me worthwhile, since it was virgin territory and the boats were bound to achieve a swift and considerable success.’

‘I believe that in certain circumstances these operations off Cape Town could be extended to cover the African ports in the Indian Ocean. This I knew would be possible in October [1942] when the Type IXD2 (1 365 tons, endurance 50 400 km) came into service. These were the “gun cruisers” of pre-war years, which had been converted into torpedo vessels, so that the torpedo was their weapon’ (Memoirs, p238).

Eisbär in the South Atlantic

Nine big attack U-boats were destined to operate in the South Atlantic by 1 October 1942. Wolfpack Eisbär (Polar Bear) comprised four veteran Type IXCs: U-68 (Karl Freidrich Merten), U-172 (Carl Emmermann), U-159 (Helmut Witte), and U-504 (Hans Georg Freidrich Poske), with a tanker, U-459 (Georg von Wilamowitz-Möllendorf). U-156 was diverted en route to Cape Town to pick up survivors from the Laconia (Blair, 1998, p57). Eisbär was expected to carry out a surprise attack on Cape Town and, if feasible, then to proceed to the Indian Ocean.

Later, the U-Cruiser Force comprised four new Type IXDs: U-178 (Hans Ibbeken), U-179 (Ernst Sobe), U-177 (Robert Gysae), and U-181 (Wolfgang Lüth). This force was to round the Cape of Good Hope at approximately the same time as Eisbär (Blair, 1998, pp57-8).

South Africa, in early 1942, was no more prepared to repel an attack than the United States had been. The British naval authorities in Cape Town controlled four destroyers and several corvettes. Owing to the heavy commitment to Operation Torch in North Africa, the British were hard-pressed to reinforce the South African ASW forces. Eventually, additional forces of ships and aircraft were despatched but were slow to arrive. The British Admiralty’s Submarine Tracking Room monitored the eight oncoming U-boats. Accordingly, shipping was drastically reduced and diverted to Durban, which was the final port of call for vessels homeward-bound from the Suez Canal, the Persian Gulf and India (Blair, 1998, p72).

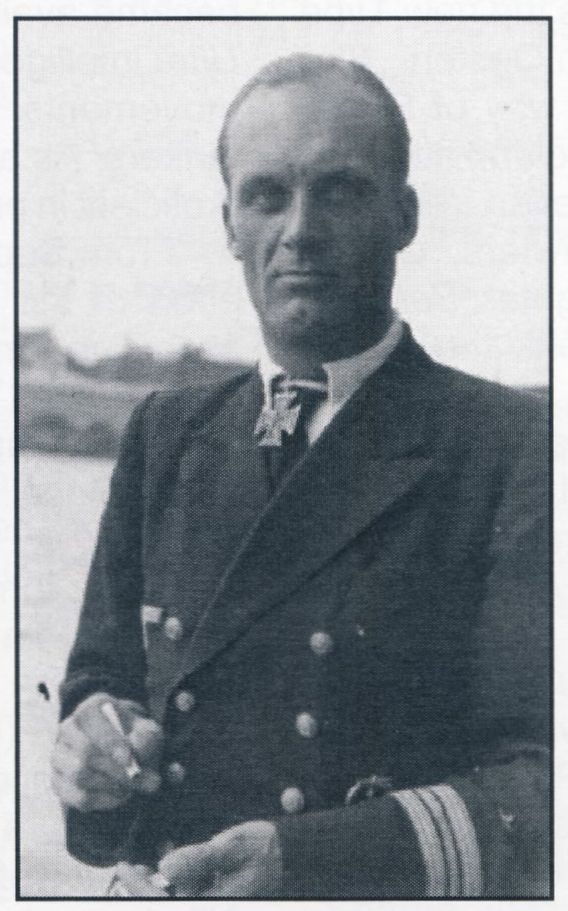

U-68 Kapt zS Karl-Friedrich Merton (1905-1993).

Eisbär Group. Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves.

Two U-boats, U-68 (Merten) and U-172 (Emmermann) were to reconnoitre the Cape Town anchorage, enter Table Bay and simultaneously commence attacking what was thought to be ‘fifty ships’. While the attack was in progress, U-159, U-504 and U-179 were to wait outside the harbour and attack ships leaving the area. What Merten and Emmermann saw instead was desperately disappointing: Table Bay anchorage was ‘empty’ and they reported the presence of many searchlights and land-based radar, which made it impossible for the U-boats to attack on the surface. Both skippers made a request for freedom of action. Permission was granted by the U-boat command and U-172 went on to the offensive. Firstly, it sank the American freighter, Chickasaw City, with two torpedoes on 7 October and then the freighter, Firethorn, again with two torpedoes. Helmut Witte (U-159) sank the freighter Boringia with a single torpedo. The U-boats continued their attack in the early hours of 8 October, U-172 sinking Pantelis with a single torpedo. Close by, Merton (U-68), after expending seven torpedoes, sank two ships in quick succession, the Greek Koumoundouros and the Dutch ship Gaastekerk. At first light, four destroyers and a corvette sailed from Cape Town to do battle, but spent most of the day rescuing survivors from the six ships. The U-boats sank one more ship that day: Clan Mactavish was torpedoed by U-172.

U-172 KK Carl Emmermann

(1915-1990). Eisbär Group.

Knight’s Cross & Oak Leaves.

After dark, Ernst Sobe (U-179) sank the British freighter, City of Athens. Still later that evening, the British destroyer, Active, reacted and rescued 99 persons. Whilst in the area, she located U-179, which was attacked and sunk with ten depth charges, with the loss of all hands. Meanwhile, Merten (U-68) had been active, sinking two ships. One was the American tanker, Swiftsure, sunk with one torpedo, and the other, the British freighter, Sarthe, with two torpedoes. Merten’s massacre continued past midnight into the early hours of the next day, when he attacked and sank two more ships: the American freighter, Examelia, with one torpedo, and the freighter, Belgian Fighter. That afternoon, Witte, in U-159, used one torpedo to sink the American freighter, Coloradan. This victory brought to twelve the number of vessels sunk off the Cape by Merton, Emmermann, Witte and Sobe in about 48 hours (Blair, 1998, pp75, 76; Sharpe, 1998, pp33, 55, 58).

The next day, 10 October, the Cape Town authorities diverted or halted most shipping in South African waters, but the Germans scored two more impressive victories operating near the Cape. Emmermann (U-172) spotted the liner, Orcades, sailing alone with 1 300 Allied troops and Axis prisoners of war on board. After a brief chase, she was hit by three torpedoes. The crew abandoned ship and, with the help of 52 volunteers who re-boarded it, the captain attempted to sail to Table Bay, but the ship was struck by another three torpedoes, which sank her.

The fourteenth and last ship to fall victim to the Eisbär boats in the South Atlantic was the British freighter, Empire Nomad. She was struck with four torpedoes from U-159 (Helmut Witte) off Cape Town. This action qualified Witte for the Ritterkreuz (Knight’s Cross). At the time, the confirmed score was fourteen ships (Blair, 1998, pp75, 76; Sharpe, 1998, p55, 58).

U-509 KL Werner Witte (1915-1943).

Eisbär Group. Sunk by Fido torpedo SW of Azores,

with the loss of all 54 hands, July 1943.

Believing that South African traffic had been diverted far to the south of the Cape, several Eisbär boats proceeded beyond latitude 40°S into the zone referred to as the ‘Roaring Forties’, known for its hurricane force storms and mountainous seas. Nonetheless, Witte (U-159) sank two British freighters with five torpedoes on 29 October, the Ross and the Laplace. Fritz Poske (U-504) reached the ‘Roaring Forties’ and sank the British freighter, Empire Chaucer, on 17 October. Since he had freedom of choice, Poske headed north towards Durban. En route he attacked two ships off East London on 23 and 26 October respectively, the American Liberty Ship, Anne Hutchinson, and the British freighter, City of Johannesburg, which broke in half. Her stern finally sank, but a minesweeper and a tugboat towed the bow to Port Elizabeth, a complete loss (Blair, 1998, p76; Sharpe, 1998, p105).

U-504 Kapt zS Fritz Poske

(1904-1984). Eisbär Group.

Knight’s Cross.

Remaining about 400 km east of the coastline to escape attacks from ASW aircraft, Poske (U504), on 31 October, sank two British freighters, the Empire Guidon and the Reynolds. With only two torpedoes remaining, he about-faced and headed home. While rounding the Cape, he expended his torpedoes to sink the Brazilian freighter, Porto Alegre. These successes raised Poske’s total to the level of Merten’s (U-68), six ships apiece. When these sinkings were added to his tally on two prior patrols, Poske qualified for, and received, the Ritterkreuz by radio (Blair, 1998, p76; Sharpe, 1998, p105).

The four Eisbär boats departed the Cape Town area in high spirits. Merten and Poske went directly to the mid-Atlantic; Witte and Emmermann to rendezvous with tanker U-461. While on his way, Witte (U-159) sank two lone American ships. The first was La Salle, sunk on 7 November, loaded with ammunition; the torpedo ignited her cargo and the resulting blast was heard in Cape Town, 500 km away. The second was the Star of Scotland, which was attacked on 13 November. Witte stopped her for food and other commodities and then sank her by gunfire. Finally, Merten, home-ward-bound, sank a British freighter and raised his score to nine ships, which qualified him for Oak Leaves to his Ritterkreuz, which came from Hitler via radio. Upon reaching France, both Merten and Poske left their boats and did not return to combat (Blair, 1998, p 77; Sharpe, 1998, p55).

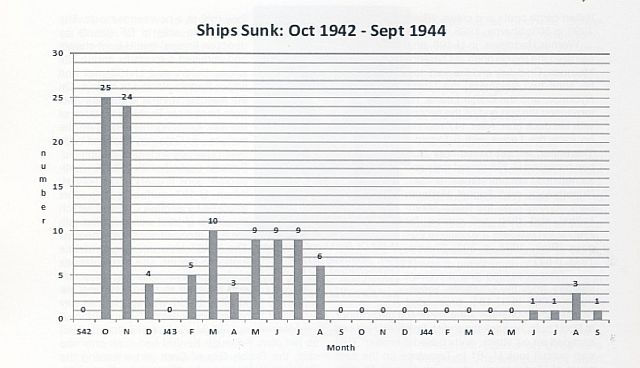

The attack by Group Eisbär on South Africa was one of the most successful operations of the war. The four Type IXs sank 24 ships between them off Cape Town and Durban. In addition, three of the four sank eleven ships to and from the Cape, raising the number of ships sunk to 34.

The U-cruisers

The other three IXD2 U-cruisers (U-178, U-177, U-181) arrived off Cape Town in late October and were confronted by intensified ASW measures, but these did not impede the Germans. Leading the pack, Hans Ibbeken, in U-178, sank the troopship, Duchess of Atholl en route, then skirted the Cape and went north to Durban. Two days off Durban, he chased a tanker and two freighters. However, on 1 November, he attacked the troopship, Mendoza. Of the 406 people on board, 26 died and were never found.

U-178 Kapt sZ Hans Ibbeken

(1899-1971). Knight’s Cross.

Earlier in the war, Ibbeken recalled that Dönitz had promised that he would be the first German skipper to circumnavigate the island of Madagascar. He did so, sinking two freighters on the way, the Norwegian Hai Hing and the British Trekieve, but, bedevilled by engine trouble, the voyage around Madagascar was unproductive (Blair, 1998, p78; Sharpe, 1998, p59).

The second and third IXD2 cruisers reached the Cape Town area almost simultaneously. Ritterkreuz-holder Robert Gysae, in U-177, was the first to find a target. On 2 November he chased and torpedoed the Greek freighter, Aegeus, which had a load of ammunition. The ship literally disappeared in an immense explosion. The next day, Ritterkreuz-holder Wolfgang Lüth, in U-181, found and attacked the American ore carrier, East Indian. The first two torpedoes missed their target, but Lüth scored hits with the next two and the ship went down. Thirty-four of her fifty-man crew were never found.

U-181 Kapt zS Wolfgang Lüth (1913-1945).

Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords and Diamonds.

(He was only the second U-boat commander awarded with this decoration).

Killed 15 May 1945 at Flensburg Müwik.

The two U-cruisers hunted off Cape Town for about ten days. Gysae attempted to sink a British tanker, but failed to do so. From 11 to 13 November, Lüth sank three more ships: Plaudit, KG Meldahl and Excello. This was enough, Dönitz ruled, to qualify him for Oak Leaves to his Ritterkreuz. The award came from Hitler. While Gysae and Lüth cruised north toward Durban, Ibbeken sank the Louise Moller.

In reaction to these attacks, ASW aircraft twice attacked U-178, driving Ibbeken down and thwarting an attack on another ship. Still plagued by engine problems, Ibbeken sailed far offshore to make extended repairs and then headed home. While rounding the Cape, he sank the American Liberty Ship, Jeremiah Wadsworth. Upon arrival in France in January, Ibbeken left U-178 for other duty (Blair, 1998, pp78, 79; Sharpe, 1998, p59).

On the day Ibbeken departed the Durban area, the British destroyer, Inconstant, responding to alarms from ASW aircraft, caught Lüth in U-181. Lüth dived deep to evade the destroyer, but the Inconstant mounted a nine-hour chase, dropping thirty depth charges. Late that afternoon, two corvettes, Jasmine and Nigella, arrived to relieve Inconstant. Jasmine dropped five depth charges, but she lost U-181. Lüth escaped in darkness and was able to repair the considerable damage. After completing repairs, Lüth cruised north for 400 km to the neutral port of Lourenço Marques (now Maputo). Patrolling in this area for the next two weeks, Lüth sank, by gun fire or by torpedo, eight ships between 13 November and 2 December. These were the Gunda, Corinthiakos, Alcoa Path finder, Mount Helmos, Dorrington Court, Evanthia, Cleanthis, and Amarylis. Lüth returned to France in mid-January, completing a voyage lasting 129 days in which he had travelled 34 190 km without refuelling (Blair, 1998, p79; Sharpe, 1998, p59).

U-177 KK Robert Gysae (1911-1989).

Knight’s Cross and Oak Leaves.

Commencing on 19 November 1942, Gysae, in U-177, also patrolled the area near Lourenço Marques. Over a period of 26 days, he expended all his torpedoes to sink seven ships: the Empire Gull, Llandaff Castle, Pierce Butler, Saronikos, Sawahloento, Scottish Chief, and the British troopship, Nova Scotia. In addition to her crew, the Nova Scotia carried 899 passengers (765 Italian prisoners of war and civilian internees and 134 British and South African soldiers). Upon learning that he, like Hartenstein in U-156, had sunk a ship carrying hundreds of Italian allies, Gysae radioed Dönitz for instructions: ‘Sank auxiliary cruiser Nova Scotia with over 1 000 Italian civil internees ex Massaua [Ethiopia]. Two survivors taken on board. Still about 400 in boats or rafts. Moved away because of aircraft.’ In his reply, Dönitz had evoked the Laconia Order: ‘Continue operating. Waging war comes first. No rescue attempts.’ (Blair, 1998, pp 79, 80; Sharpe, 1998, p59).

Dönitz notified the Portuguese authorities, who despatched vessels from Lourenço Marques to carry out the rescue. A Portuguese sloop rescued 192 survivors (including 43 South Africans) in boats and rafts, surrounded by ravenous sharks. Including the crewmen, about 750 persons perished. One hundred and twenty corpses were washed up on the Natal north coast, sharks having consumed many of the remaining 630. At Gysae’s request, the crew of U-177 signed a pledge never to discuss the catastrophe (Blair, 1998, p80; Sharpe, 1998, p59). Gysae, in U-177, returned to France in late January, completing a patrol of 128 days with a confirmed score of eight ships. Like Lüth, he remained with his boat to prepare for another patrol to the Indian Ocean.

The four German U-cruisers operated off Cape Town and Durban and sank 28 ships, confirmed. (Blair, 1998, p80).

The Seehund foray into southern waters

In January 1943, Group Seehund (seal) represented the second foray to the Cape and the Indian Ocean. The tanker U-459 accompanied the boats to the South Atlantic. There were five in the group: Type IXCs U-160 (Georg Lassen), U-506 (Erich Würdermann), U-509 (Werner Witte), and U-516 (Gerhard Wiebe); and Type IXD2 U182, commanded by Nikolai Clausen.

U-179 FK Ernst Sobe (1904-1942).

U-179 was depth-charged, rammed and sank

off Cape Town with all 61 hands.

The first to sink a ship was George Lassen, in U-160. A recipient of the Ritterkreuz, Lassen proceeded to the area south-east of Cape Town. On 2 March 1943 he found a poorly organised and thinly escorted convoy of ten heavily laden merchant ships and four escorts. Favouring the dark, on 3 March, he shot eight torpedoes at the convoy, sinking five ships: the Harvey W Scott, Nipura, Empire Mahseer, Marietta and Sheaf Crown (Sharpe, 1998, p55). Lassen’s flash report electrified U-Boat Control. Dönitz immediately initiated steps to award Oak Leaves to Lassen’s Ritterkreuz. The message of congratulations came from Hitler via radio. In the second week of March, Lassen sank the American Liberty Ship, James B Stephens, and the British freighter, Aelybryn. With seven sinkings confirmed and another two ships damaged, Lassen advised U-Boat Control that he was down to three torpedoes and coming home. He arrived in France in May after 125 days at sea. He left his boat for a job in the Training Command (Blair, 1998, p227; Sharpe, 1998, p55).

U-160 KK Georg Lassen (1915-2012).

Knight’s Cross & Oak Leaves.

East of Cape Town, Würdermann, in the IXC U-506, sank the British freighter Sabor after firing five torpedoes. He moved to the sinking ship and struck an object, damaging the periscope and propeller, which forced him to withdraw south of Cape Town to make repairs. While so engaged, the Norwegian freighter, Tabor, happened by, and Würdermann sank her using three torpedoes. When these were added to his prior sinkings during patrols in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, Würdermann qualified for the Ritterkreuz.

U-506 KL Erich Würdermann (1914-1943).

Knight’s Cross. One of 49 killed in an air attack

west of Spain, July 1943. Six taken prisoner.

Werner Witte, in the IXC U-509, embarked on his third patrol and sank his first ship south-east of Cape Town on 11 February. She was the Queen Ann, which sank after a hit with one torpedo. Remaining off Cape Town without sinking a ship, Witte doubled back to Saldanha Bay for two more weeks without sinking a ship. On 2 April, he located a small convoy and, approaching it submerged, fired four torpedoes. Two hit the British ship, City of Baroda, which limped into Lüderitz and beached, resulting in a complete loss. Running short of food, U-509 commenced the return voyage in late March. Witte reached France on 11 May (Blair, 1998, p228).

U-boat Control mounted a special mission in the Indian Ocean. The task was to meet a Japanese submarine for the purpose of exchanging personnel and cargo. The German U-boat selected for this mission, U-180, was the new IXD1, commanded by Werner Musenberg. The 1 600-ton boat was the fastest diesel boat yet produced. After rounding the Cape, Musenberg found and sank the British tanker, Corbis. On 26/27 April 1943, he met a Japanese submarine south of Madagascar. After an exchange of personnel and cargo, the U-180 headed for home. On her second voyage, this U-boat, bound for Penang, struck a mine near France and was lost with 56 hands on board (Blair, 1998, p 232; Sharpe, 1998, p59).

U-182 KK Asmus Nicolai Clausen (1911-1943),

Knight’s Cross. Depth-charged and sunk 300 km WNW

of Madeira with the loss of all 61 hands, May 1943.

The Type IXC U-516, commanded by Gerhard Wiebe, during his second patrol, sank three ships south-east of Cape Town. They were the British and American freighters, Helmsprey and Deer Lodge respectively, and the Dutch submarine tender, Colombia, taking down several Dutch submarine crews. Wiebe reported that he had accidentally rammed the wreckage of the Colombia and was withdrawing to the south to make repairs and to fix an oil trace. Later, he reported that he had ‘stomach pains’ so severe that it was necessary to abort the patrol. He arrived in France in early May, completing a 132-day patrol. His illness led to his transfer from U-516 to other duty (Blair, 1998, p 228; Sharpe, 1998, p108).

U-516 FK Gerhard Wiebe (1907-1985).

Seehund Group. Knight’s Cross.

The new IXD U-cruiser U-182, loosely attached to Seehund, was commanded by Nikolaus Clausen, who had won the Ritterkreuz for earlier successes. Rounding the Cape, he sank the British freighter, Llanashe. Clausen cruised to Durban, Lourenço Marques and the Mozambique Channel, and then to the west coast of Madagascar. The outcome was a great disappointment to him – Clausen sank only one ship, the American Liberty Ship, Richard D Speight. On the return voyage, he sank two freighters, the British Aloe and the Greek Adelfotis. On reaching a point west of Maderia, U-182 was depth-charged by two American destroyers, sinking with the loss of 61 hands (Blair, 1998, p 229; Sharpe, 1998, p 60).

On the whole, Seehund, the second foray into the Indian Ocean, was judged to be only modestly successful. The five boats sank eighteen ships, confirmed. Lassen, in U-160, sank seven, Clausen (U-182), four, Wiebe (U-516), three and Würdermann (U-506) and Witte (U-509), two apiece. (Blair, 1998, p 250).

The third U-boat foray

For third foray, Dönitz directed U-boat Control to mount an offensive in the Indian Ocean in March and April 1943. Seven U-cruisers were designated for the task: U-198, U-196, U-195, U-197, U-181, U-177 and U-178. Allied code-breakers, in due course, provided details about the seven-boat foray and the Admiralty notified the appropriate naval commands. On 4 May the War Diary of the British South Atlantic Command recorded: ‘In view of the approaching U-boat threat, complete convoy system round South Africa coast was reintroduced. All independent sailings were suspended except fast ships. All vessels approaching Cape Town were diverted to reach coastal area early.’ (Blair, 1998, p 297).

Type IXD2 U-198 was under the command of Werner Hartmann. He rounded the Cape and sailed into the lower Mozambique Channel to find a south-bound convoy from Lourenço Marques to Durban. It comprised six big freighters, thinly escorted by two ASW trawlers and one aircraft. On 17 May, Hartmann attacked and sank the British freighter, Northmoor. The ASW trawlers dropped fifty depth charges and the aircraft dropped five. There was no serious damage. On the following day, Hartmann found and chased two freighters. He was spotted and hounded by a submarine chaser for the whole day and into the night. The next week, he found yet another convoy near Durban. It was heavily escorted by warships and aircraft, forcing Hartmann to leave the area. He cruised about 600 km eastward, where he found and sank the lone British freighter, Hopetarn, on 29 May. Later, he attempted to confront a small convoy, but ASW measures thwarted any attempts to attack (Blair, 1998, p 297; Sharpe, 1998, p 62).

U-198 Kapt zS Werner Hartmann (1902-1963).

Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves.

Returning to the Durban area, Hartmann found the prospects more favourable and, on 5 June, he sank the British freighter, Dumra. The next day, he sank the American Liberty Ship, William King (Blair, 1998, p297; Sharpe, 1998, p62).

In early June, U-boat Control decided that all U-cruisers which had plenty of torpedoes should extend their patrols. It was therefore arranged that boats were to replenish fuel supplies from the German tanker, Charlotte Schliemann, in the Indian Ocean at a remote site about 2 900 km due east of Durban and about 1 000 km south of Mauritius (Blair, 1998, p 298).

The second of the new U-cruisers, Type IXD2, was the U-196. She was commanded by Eitel-Friedrich Kentrat, who had won the Ritterkreuz operating the North Atlantic. He skirted the Cape and then swung northward to the area near Durban. On 11 May, he shot off two torpedoes and sank the British freighter, Nailsea Meadow. Three weeks later, he patrolled near Durban again until 1 June, then turned east for refuelling by the Charlotte Schliemann (Blair, 1998, p298).

U-196. KK Eitel-Friedrich Kentrat

(1906-1974). Knight’s Cross.

The third new U-cruiser was the Type IXD1 U-195 commanded by Heinz Buchholz. He followed a similar route as that of Hartmann, but not before sinking two ships off West Africa. After an encounter with a lone American vessel off Cape Town which he failed to sink, he remained in the area, but found no more targets. Beset with engine problems, U-195 headed for base and arrived in Bordeaux on 23 July (Blair, 1998, p298).

U-195 KK Heinz Buchholz (1909-1944).

Killed February 1944 in an air attack

860 km WSW of Ascension Island.

The fourth and last of the new cruisers was the U-197. The experienced skipper of the IXD2 was Robert Bartels. By the time he reached the Cape, it was time to refuel with the Charlotte Schliemann. In 81 days at sea, Bartels, like Kentrat, did not sink a single ship (Blair, 1998, p 290).

U-197 KL Robert Bartels (1911-1943).

Sunk in air attack, 400km SSW of Madagascar,

August 1943, with the loss of all 67 hands.

Of the three experienced skippers, the first to sail was the U-cruiser Type IXD2 U-181 under Wolfgang Lüth who wore Oak Leaves with his Ritterkreuz. On his twentieth day at sea, he sank a British refrigerator ship off West Africa.

Upon learning of the sinking, Dönitz arranged with Hitler to add Crossed Swords to the Oak Leaves of Lüth’s Ritterkreuz. Lüth was the 29th recipient in all the German armed forces and the fourth submariner to receive this high decoration. When the news reached U-181 by an encoded message, the crew celebrated with beer and cognac (Blair, 1998, p299).

Lüth rounded the Cape and went north to patrol the waters off Lourenço Marques. Here he had success on his first patrol to the Indian Ocean. Lüth patrolled the waters to as far south as Durban for a full month. In that time, he sank three more lone ships: On 12 May 1943, the British freighter, Tinhow; on 20 May, the Swedish Sicilia with ten deck gun rounds and a torpedo; and on 7 June 1943, the small South African coaster, Harrier, filled with ammunition which ‘vapourised’ with one torpedo. As per plan, Lüth arrived [at] the rendezvous with Charlotte Schliemann after 92 days at sea (Blair, 1998, p 300; Sharpe, 1998, p 59).

The next U-cruiser to leave Bordeaux was the IXD2 U-177, commanded by the experienced Ritterkreuz-holder, Robert Gysae. Like Lüth, this was Gysae’s second patrol to Cape Town. On this trip, he was equipped with a new day-search device: a one-man, three-rotor, helicopter known as Bachstelze. It was tethered to the U-boat by a 300 metre cable, could reach a height of 180 metres and the pilot could search a radius of about 40 km. Off the Cape, Gysae came upon a convoy of sixteen ships escorted by seven warships en route from Cape Town to Durban. On 28 May, he sank the American freighter, Agwimonte, and the Norwegian tanker, Storaas. Upon hearing of this success, Dönitz radioed Gysae with the news that Hitler had awarded him Oak Leaves to his Ritterkreuz. At the suggestion of U-boat Control, Gysae was ordered to the Saldanha area, but failed to sink a single ship. Thereafter, he set off for a rendezvous with Charlotte Schliemann. He was at sea for 87 days and sank two ships (Blair, 1998, p 301; Sharpe, 1998, p 59).

The third and last experienced U-cruiser of the foray was the cruiser Type IXD2 U-178. It was her second cruise to the Indian Ocean, but she had a new skipper, Wilhelm Dommes. He was awarded the Ritterkreuz for success in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Dommes reached the Cape in early May and, in the third week, he found a small convoy. Attacked by depth charges dropped from the air, Dommes was forced to dive and lost contact with the convoy.

Patrolling off Durban and despite the surface escorts and Catalina aircraft, Dommes attacked on 1 June and damaged the Dutch freighter, Salabangka. The convoy’s tug towed the damaged ship, but a storm arose, and she broke up and sank. Dommes patrolled near the Mozambique Channel for several days, then turned east to rendezvous with Charlotte Schliemann. Like Kentrat in U-196 and Bartels in U-197, in all that time, Dommes sank only one ship. The skippers of the six U-cruisers replenishing at Charlotte Schliemann visited back and forth, exchanging experiences. All were replenished with fuel, water, and lubricating oil (Blair, 1998, p301; Sharpe, 1998, p 59).

In the Indian Ocean

U-boat Control issued orders to the six U-cruisers. They were to remain in the Indian Ocean and mount simultaneous attacks on Allied shipping: Lüth (U-181) was to go to Mauritius, Hartmann (U-198) to Lourenço Marques, and Kentrat (U-196) to sweep south down the Mozambique Channel. Meanwhile, Dommes (U178) would sweep south to north, Gysae (U-177) was to patrol south of Madagascar, and Bartels (U-197) was to patrol close inshore in the area between Lourenço Marques and Durban. (Blair, 1998, p302).

Gysae (U-177) patrolled south of Madagascar and, in early July, carried attacks on three lone freighters. The first got away when he missed with two torpedoes. The second, he sank with three torpedoes. This was the Canadian Jasper Park. In the third attack, closer to Madagascar, he sank the American Liberty Ship, Alice F Palmer, with two torpedoes and 99 rounds from his deck gun (Blair, 1998, p302; Sharpe, 1998, p59).

Returning to the area well south of Madagascar, Gysae saw nothing for days. Finally, on 29 July, he sank the British freighter Cornish City.

Later, on 5 August, he sank the Greek Efthalia Mari. Having sunk four ships on this cruise, Gysae returned to France. The return trip took 58 days; the entire patrol lasted 184 days. On his arrival in France, Gysae left U-177 to command a training flotilla. Heinz Buchholz, the skipper of U-195, replaced Gysae as skipper of U-177 (Blair, 1998, p 302).

U-178 FK Wilhelm Dommes (1907-1990).

Knight’s Cross.

Dommes, in U-178, cruised slowly near the Mozambique Channel. Near Lourenço Marques on 4 July, he sank two freighters: the Norwegian Breiviken and the Greek Michael Livanos. He remained in an area north of Lourenço Marques and, in the second week of July, he torpedoed and sank two big freighters: the Greek Mary Livanos, the American Liberty Ship, Robert Bacon.

Having received fuel from the Italian submarine, Torelli, both boats proceeded to the island of Penang in Malaysia. Dönitz and the OKM Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine) decided to establish a U-boat base on the island to accommodate big German cruisers, cargo boats and Italian cargo boats and crews.

Werner Hartmann, in U-198, also patrolled the region north of Lourenço Marques. On 6 July and the next day, he sank two freighters, the Greek Hydraios, and the British Leana. He torpedoed the first and hit the second with his deck gun. After 147 rounds, he sank the Leana with a torpedo. Thereafter, aircraft based near Durban harassed U-198 almost daily and sometimes several times daily. Nonetheless, on 1 August, Hartman sank another ship, the Dutch Mangkalibat and then set course for France to complete a voyage of 201 days (Blair, 1998, p 303; Sharpe, 1998, p 62).

After recruiting one merchant seaman from the Charlotte Schliemann, Lüth, in U-181, proceeded northward to Mauritius. After surveying the harbour at Port Louis, he sank the British freighter, Hoihow, escaped an air attack, and chased a cruiser. This vain pursuit took U-181 to Tamatave on the east coast of Madagascar, where, on 15 and 16 July, Lüth sank two British freighters sailing alone, the Empire Lake and Fort Franklin. When U-boat Control learned that Lüth was operating off the east coast of Madagascar, it ordered him to return to Mauritius. In compliance, Lüth headed eastward slowly. On 4, 7 and 11 August, he sank three more British ships, sailing alone. These were the Dalfram, the Umvuma and the refrigeration ship, Clan MacArthur (Blair, 1998, p 303; Sharpe, 1998, p 59).

Upon learning of these successes, Dönitz recommended to Hitler that Lüth be given Germany’s highest award, Diamonds to the Oak Leaves and Crossed Swords. Hitler approved this. Lüth thus became the first in the Kriegsmarine and the seventh in the Third Reich to be so honoured. When Dönitz radioed his congratulations to Lüth, the officers and crew celebrated with beer and cognac. Thereafter, Control directed Lüth to rendezvous with Bartels in U-197, south-east of Madagascar (Blair, 1998, p304).

By mid-August, since leaving the Charlotte Schliemann, Bartels, in U-197, had sunk only one ship, the Swedish tanker, Pegasus. At the end of August, Lüth, in U-181, intercepted a report from Bartels to Control, which stated that he, now on his third patrol, had sunk another ship, the British Empire Stanley. This action delayed him some distance from Lüth and, accordingly, they met at a new rendezvous. The Allies were able to DF (locate by direction finding) this U-boat chatter and obtained a rough fix on the site where U-181 and U-197 met and where Bartels elected to remain. On 20 August, several Catalinas flew from base near Durban in search of the site. Locating the U-boat on the surface, a Catalina attacked with depth charges and machine gun fire. Bartels replied with FLAK (anti-aircraft gun) fire and crash-dived. When U-197 surfaced, she was attacked by another Catalina, which raked the U-boat with machine gun fire and dropped six depth charges. The U-197 blew up, flinging debris high into the air. The two Catalinas circled an ever-widening oil patch and returned to base, claiming the kill. The U-197 was lost on this day with all 67 hands on board (Blair, 1998, p304).

(Blair, 1998, p 303; Sharpe, 1998, p59)

Meanwhile, Lüth (U-181) met Kentrat (U-196) as per plan. Although Kentrat had sunk only one ship, the British City of Oran, since leaving the Charlotte Schliemann, he generously offered Lüth five of his torpedoes. Lüth declined, stating that he barely had enough fuel to return to France. Both then went in search of Bartels and, after a futile search lasting three days, both U-boats set course for France and arrived safely at base. U-181 had completed a voyage of 225 days, having sunk nine ships, while U-196 had sunk two. Lüth went to Hitler to receive his two awards (Crossed Swords and Diamonds). Later, he was posted to the Baltic to command a training flotilla (Blair, 1998, p305).

The overall returns of the U-cruiser foray to the Indian Ocean were mixed. Seven U-cruisers had sailed. Of these, two had been lost: one (U-197) sunk, and one (U-195) aborted. However, Lüth, Hartmann, Gysae and Dommes bagged 22 ships between them, while three cruisers (U-195, U-196, U-197)had sunk only seven ships (Blair, 1998, pp305-6).

U-198

The third U-cruiser to sail in April 1944 was the veteran IXD2 U-198, commanded by a new skipper, Burkhard Heusinger Waldegg. Off Cape Town, he sank the South African freighter, Columbine. After rounding the Cape into the Indian Ocean, he survived an attack from the air before proceeding north into the Mozambique Channel, where he sank three British freighters, Director, Empire City, and Empire Day. On 12 August, a British Catalina took up the tracking and homed in on the British frigates, the Findhorn and Parret, and the Indian sloop, Godavari. The Findhorn and Godavari teamed up and destroyed U-198 with depth charges and Hedgehogs, anti-submarine weapons firing spigot mortar bombs that exploded on impact. There were no survivors. The 67 dead included the captain of the British freighter, Empire Day, whom Waldegg had taken prisoner. The U-198 was sunk 850 km north-north-east of Madagascar (Blair, 1998, p 540; Sharpe, 1998, p 62).

U-198 OL Burkhard Heusinger

von Waldegg (1920-1944.

U-861

The last U-cruiser to sail in April was the new Type IXD2 U-861, commanded by Jürgen Oesten. She was to patrol the Indian Ocean by way of Brazil. After rounding the Cape, U-861 found and attacked a convoy near Durban comprising seven freighters thinly escorted by three ASW trawlers. On 20 August, Oesten sank the British freighter, Berwickshire, and on 5 September, he sank the Greek freighter, Ionnis Fafalois. Thereafter, he proceeded to Penang completing the voyage lasting 156 days (Blair p540; FF p148).

U-861 KK Jurgen Oesten

(1913-2010). Knight’s Cross.

A new tanker, the U-490, skippered by Wilhelm Gerlach, dubbed ‘Milk Cow’ by the Allies, set sail for the Far East. In addition to oil, she carried a large cargo of supplies, spare parts and electronics. She made her way slowly southwards, running submerged during daylight hours. Pursued by an American Hunter-Killer group, she survived three hits from Hedgehogs and nine depth charges on 11 June. Caught unawares, Gerlach took the boat to a depth of nearly 350 metres, but the Hunter group was determined to press on. Another ship joined the group and, for fifteen hours on 12 June, the four ships dropped 25 depth charges, but caused no serious damage to the U-boat. Performing a tactical trick by sending away two of the ships in a northerly direction and one on a southerly course, the group’s three ships used gunfire to attack the submarine when she surfaced. The boat was scuttled and sank, but the 60 crewmen were rescued (Blair, 1998, p 542; Sharpe, 1998, p105).

The fate of U-boat warfare in the War

As counter measures improved, better technology became available in the form of radar. The secret Ultra intelligence provided advanced knowledge of movements, and refuelling rendezvous with U- tankers. As a result, convoy escorts became more proficient in protecting shipping from U-boat attacks.

From September to November 1942, the main effort of the U-boat force shifted from an all-out assault in American waters back to the main North Atlantic run. The renewed Atlantic campaign was again interrupted by the Allied invasion of North- West Africa on 8 November 1942, code-named Torch.

Dönitz turned his attention to the South Atlantic and the Indian Ocean. Technical innovations such as direction finding, High Frequency/Direction Frequency (HF/DF), the Leigh Light and new anti-service radar enabled the Allies to take full advantage of the of the Ultra intelligence which provided information of U-boat movements. In June 1943 the Allied naval coding system was radically altered and the German decrypting service was left ‘in the dark’. By this time, the tide of the war at sea had turned.

With the monthly reduction in tonnage destroyed, U-boat Command had to adopt riskier tactics and suffer heavier losses simply to continue the struggle. More U-boats were sunk by very long-range patrol aircraft, by escort carriers and by the ever- growing number of convoy escorts, all aided by the rapidly improving technology. As they were successfully attacked, greater experience was gained in anti-submarine tactics, which improved the rate of detection and success in subsequent attacks.

May 1943 in the North Atlantic proved a disastrous month for the U-boat Command, as 41 U-boats were lost. From June to September 1944, the first three months of the Allied invasion of Western Europe, the U- boat arm was forced to abandon all five bases in France and flee to Norway or Germany. By then, the U-boat forays to the Indian Ocean were not considered a priority.

The Cost

The Allies lost 110 ships and 2 359 lives (seamen and civilians). There were 7 830 survivors.

The Axis lost 20 U-boats: 15 sunk by the Allies, one scuttled, one lost at sea, and three surrendered. A total of 642 crewmen perished.

U-Boat Statistics

Type IXC

Displacement 1 120/1 232 tons, range 21 520 km, torpedoes 22, crew 48 to 56, maximum depth 230 metres.

Type IXD

Displacement 1 616/1 804 tons, range 43 370 km, torpedoes 24, crew 55 to 63, maximum depth 230 metres.

On 11/12 February 1944, the Charlotte Schliemann was destroyed by gunfire. The crew abandoned ship and 41 were rescued.

The U-Boats

U-68. Type 1XC. Vessels sunk: 34 (six off SA). Fate: U-68 was sunk in April 1944, bound for the Caribbean, with the loss of 56, including the commander Albert Lauzemis.

U-160. Type IXC. Vessels sunk: 25 (7 off SA). Fate: Sunk by Fido torpedo, July 1943, 400 km South of Azores with all 54 hands, including the commander, Gerd Pommer-Esche.

U-172. Type IXC. Vessels sunk: 27 (four off SA).

Fate: Sunk by air

and sea attack December 1943, 300 km SW of Canary Isles. Lost with 13 hands.

The commander, Hermann Hoffmann, and 45 hands were rescued and taken prisoner.

U-177. Type IXD2. Vessels sunk: 16 (10 off SA).

Fate: In February

1944, air attack, 880 km WSW of Ascension Island. 50 hands lost,

including the commander, Heinz Bucholz. Ten taken prisoner.

U-178. Type IXD2. Vessels sunk: 12 (ten off SA).

Fate: August

1944. Blown up at Bordeaux as it was unseaworthy.

U-179. Type IXD2. Vessels sunk: 1 (off SA).

Fate: August 1942. Depth charged, rammed and finally sank off Cape

Town with all 61 hands, including the commander, Ernst Sobe.

U-180. Type IXD1. Vessels sunk: 1 (off SA).

Fate: Detonated a mine 80 km SW of the Gironde River with a loss of all

56 hands, including the commander, Rolf Reisen.

U-181. Type IXD2. Vessels sunk: 27 (19 off SA).

Fate: In May 1945,

was handed over to the Japanese Navy, surrendered to USN and scuttled

in February 1946.

U-182.Type IXD2. Vessels sunk: 5 (three off SA).

Fate: In May

1943, depth charged and sunk 300 km WNW of Madeira with a loss of

all 61 hands, including the commander, Asmus Nicolai Clausen.

U-196. Type IXD2. Vessels sunk: 3 (two off SA).

Fate: Lost in

November or December 1944 by unknown cause in Sunda Strait with all

65 hands, including commander Johannes-Werner Striegler.

U-197. Type IXD2. Vessels sunk: 3 (two off SA).

Fate: Sunk in an

air attack in August 1943, 400 km SSW of Madagascar, and lost with all

67 hands, including the commander, Robert Bartels.

U-198. Vessels sunk: 11 (11 off SA).

Fate: Depth charged in August 1944, 900 km NNE of Madagascar, sunk

with a loss of all 66 hands, including the later commander, Burkhard

Heusinger von Waldegg.

U-504. Type IXC. Vessels sunk: 16 (six off SA).

Fate: Depth charged

in July 1943 off Cape Ortegal. Lost with 53 hands, including the

commander, Wilhelm Luis.

U-506. Type IXC. Vessels sunk: 16 (two off SA).

Fate: July 1943.

Air attack West of Spain, 49 killed, including the commander, Erich

Würdermann. Six of the crew were taken prisoner.

U-509. Type IXC. Vessels sunk: 4 (two off SA).

Fate: In July 1943,

was sunk by Fido torpedo SW of the Azores and lost with all 54 hands.

U-516. Type IXC. Vessels sunk: 16 (four off SA).

Fate: Surrendered

in July 1945 and disposed of in Operation Deadlight (The destruction of

captured U-boats off Ireland).

U-861. Type IXD2. Vessels sunk: 3 (two off SA).

Fate: Surrendered

Trondheim, Norway. Towed to Ireland for Operation Deadlight, then sunk

by gunfire in December 1945.

Kriegsmarine ranks

Kapt zS (Kapitän zur See) Captain

FK (Fregattenkapitiän) Captain Junior Grade

KK (Korvettenkapitän) Commander

KL (Kapitänleutenat) Lieutenant-Commander

OL (Oberleutant zur See) Lieutenant-Senior

Bibiography

Blair, Clay, Hitler’s U-Boat War, Volume 2 (New York, 1998).

Sharpe, Peter, U-Boat Fact File (Leicester, United Kingdom, 1998).

www.u-boat.net

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org