The South African

The South African

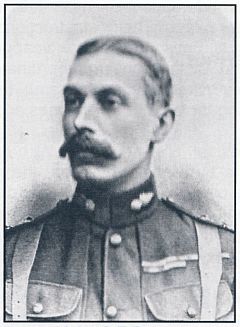

Major George Elliot Benson was one of a number of officers sent to South Africa on ‘special assignment’ before the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War in 1899. He was one of the British Army’s more promising young officers and clearly earmarked for promotion (see Benson, 1893). For these officers, intelligence about local conditions was their special assignment and they became a major source of this vital information.

At the start of hostilities, Major Benson was attached to Lieutenant- General Lord Paul Methuen’s force advancing from the Orange River to relieve Kimberley, then besieged by the Boers under General Piet Cronjé. Benson guided the Highland Regiments as they advanced in darkness before dawn on 11 December 1899 to attack the Boers entrenched at the foot of the hill at Magersfontein.

When they were close to the Boer line, Major Benson advised Scottish Major-General Andrew Wauchope to have his men deploy into open order. However, Wauchope wanted to get closer before giving this order, with the result that the Boers opened fire while they were still closed up. Magersfontein was the second of the three British reverses in December 1899 that became known as ‘Black Week’.

At first, as staff officer to Lord Methuen, Benson’s performance was such that Methuen was loath to lose him. He was advanced to the rank of lieutenant-colonel and DAAG (Deputy Assistant Adjutant General) at Headquarters in Pretoria. He had first come to the notice of Lord Kitchener in the campaign to recapture Khartoum in 1898. The Commanding General in South Africa, Kitchener, determined that he should be deployed in the field rather than as a staff officer. In May 1901 he was given command of a column and operated first in the western Transvaal, but was soon put under Lieutenant-General Sir Bindon Blood, north of the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay railway line. Operations by Blood’s columns against General Ben Viljoen along the Olifants River caused the Boer general to retreat northwards into the bushveld (Amery, ed, Vol V, p 299).

Night raids

Colonel Sir Henry Rawlinson was probably the first to adopt the method of night raiding. Shortly after his return to South Africa – he had left for England with Lord Roberts when he thought the war was practically over – Rawlinson was involved in the ambush of a Boer laager on the farm Goedvooruitzicht, 20 km north of Klerksdorp. This was one of the first dawn raids on a Boer laager which became such an effective tactic when good intelligence of the whereabouts of such a laager was available. In the confusion of the attack, some of the Boers managed a counter-attack and Rawlinson was actually in the hands of his enemy for a short while. His horse had been shot from under him and he was probably not wearing any rank insignia, so the Boers were unaware of the identity of their distinguished prisoner. Rawlinson managed to escape when the guns of ‘P’ Battery of the Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) opened fire. (The story is told in Amery, Vol V, p228, but I have not been able to find another reference.)

During daytime it was difficult, indeed nigh impossible, to locate and trap the scattered Boer commandos who could easily evade the British columns sent against them. In July 1901, Kitchener issued orders for the formation of a small number of special columns, noting that ‘[t]he enemy are now so reduced in numbers and dispersed that greater mobility is required to deal with them’. Benson took charge of one of those columns, by then promoted to the rank of full colonel. This technique of raiding Boer laagers at dawn, after intelligence was acquired of the location of such places the previous day by African scouts, now had official sanction at the highest level (Amery, Vol V, p322).

By the middle of 1901 the British system of night raids was garnering 1 500 Boer prisoners per month as well as their wagons, carts and weaponry. These losses the Boers could not replace. Their rifles and ammunition were almost all British Lee- Enfield weaponry captured in the field. Clothing and food were not plentiful. The two Boer governments were fugitives in the field, not halting for very long in any one place.

Benson was particularly successful. His men were well-trained with scouts who had intimate knowledge of the locality and its people. There were infantry and artillery to protect his campsites and mounted men to ride out nightly to targets pointed out by scouts directed by his intelligence officer. It took some months for his column to become fully-trained and, by October 1901, his very success caused the Boers to want to find some way to eliminate him. Amery (Vol V, pp 330-1) gives some detail of Benson’s raids in the area. Chris Ash (2017, pp 455-6) describes Benson’s methods of night raiding.

Major G E Benson

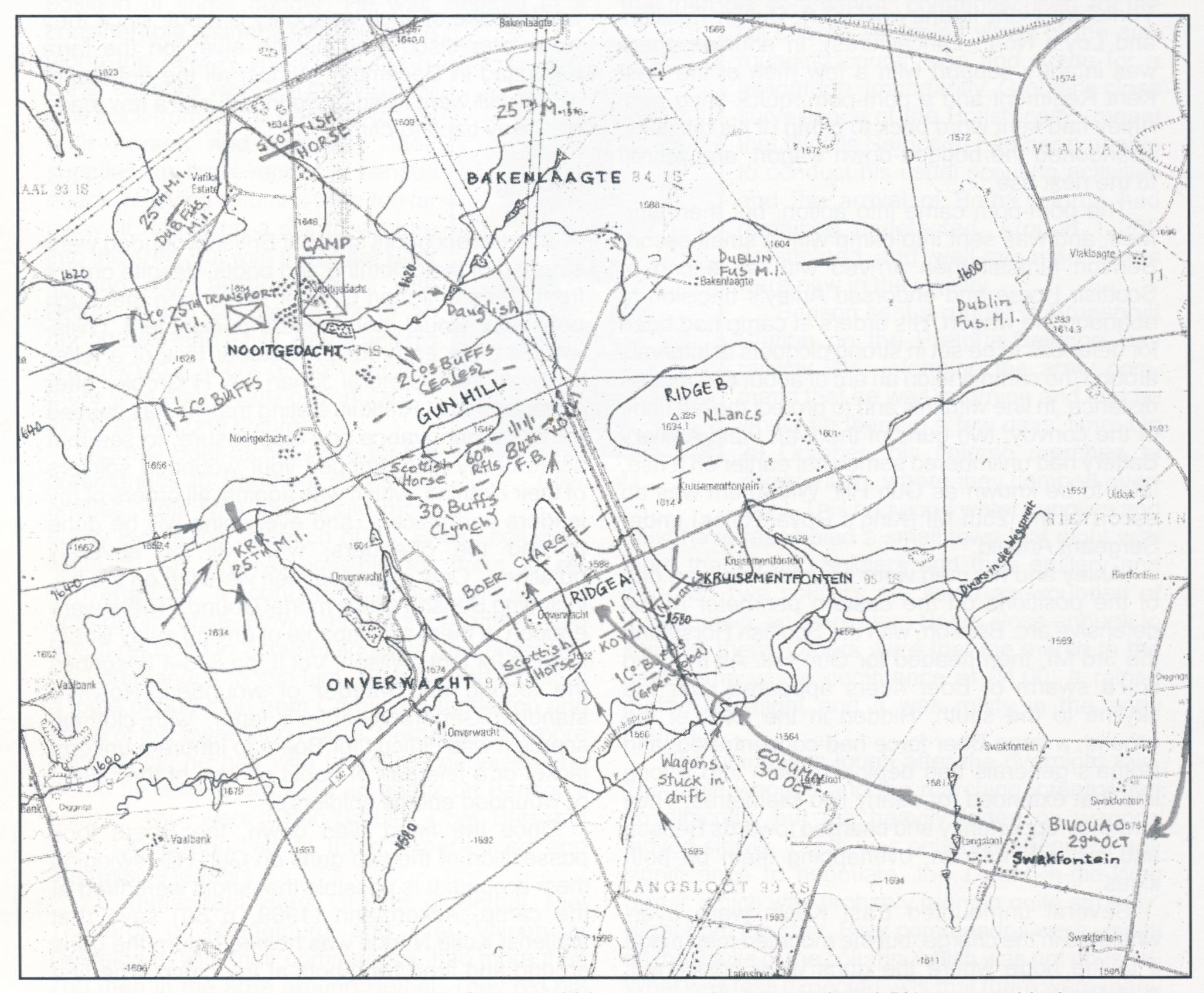

In the resulting Battle of Bakenlaagte on 30 October 1901, Benson was mortally wounded and more than 130 of his men were killed and wounded in the fierce action that began in misty and rainy weather. As usual the Boers were reluctant to risk the serious casualties which would have been the inevitable result of an assault on the British column, camped and fortified around the farmhouse of Nooitgedacht. (The battle, although fought almost entirely on the farm Nooitgedacht, goes under the name of Bakenlaagte, the adjacent farm, probably to avoid confusion with the battle fought on Nooitgedacht in the Magaliesberg between de la Rey, Beyers and Smuts and Major-General Ralph Clements on 13 December 1900).

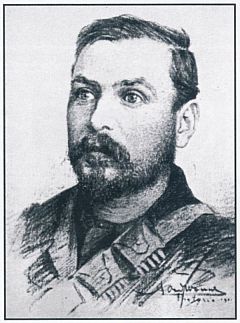

Louis Botha

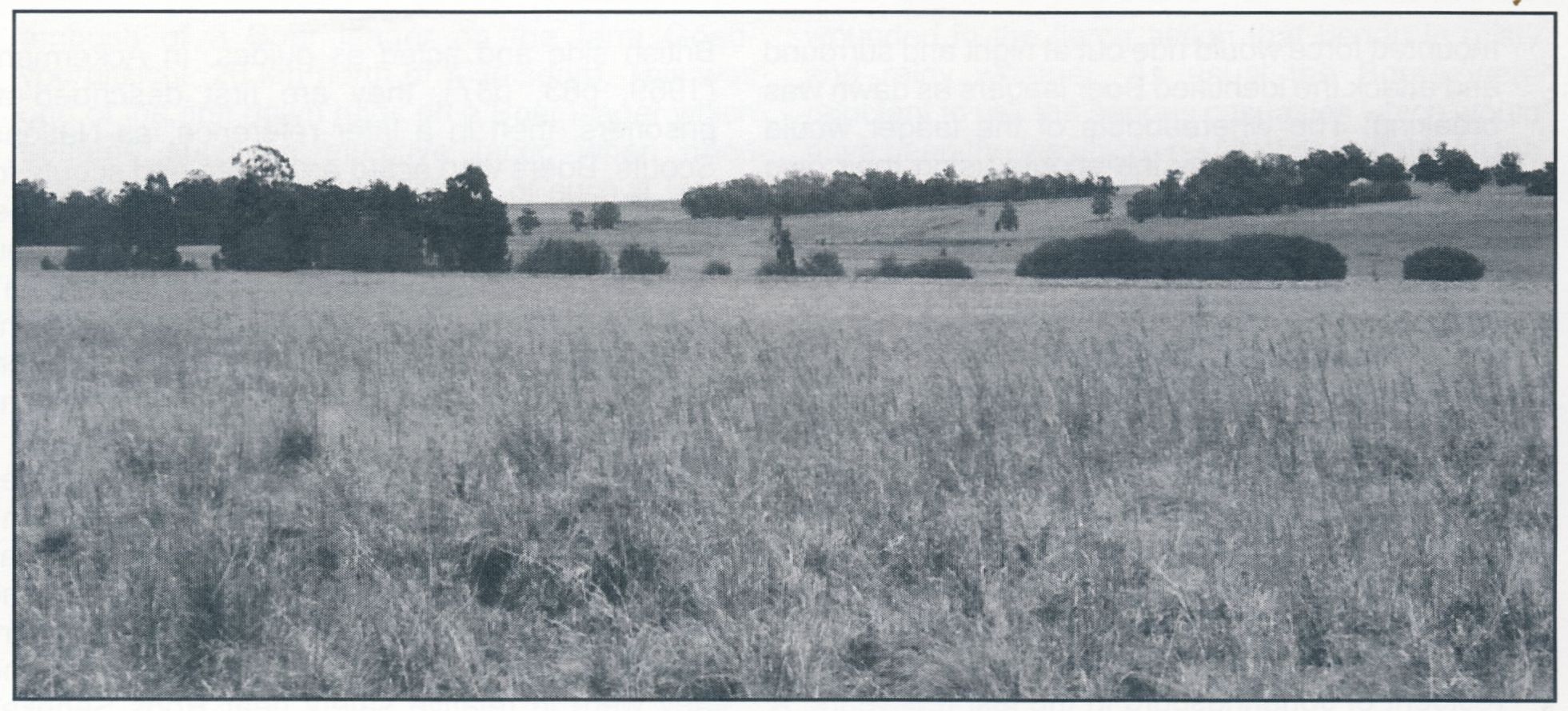

Bakenlaagte, looking south from Nooitgedacht Farmhouse.

Gun Hill is the clump of trees on the skyline to the left.

(Photo: R Smith).

Prelude to the battle

In September 1901, Boer Generals Jan Smuts and Louis Botha acted upon the resolutions taken at the Waterval krygsraad in June to undertake raids into the British colonies of the Cape and Natal. Smuts gathered up 300 experienced men from Koos de la Rey’s western Transvalers and made his way through the Free State, evading the pursuing British columns. Botha’s foray was on a rather larger scale – as many as 2 000 of his burgers wanted to take part, but there were not that many horses in the necessary condition to undertake such an arduous expedition. In the end, his force comprised scarcely 1 400 men (Moore, 1979).

With the departure of the sizeable forces of Boers under Smuts and Botha for their respective theatres, there were very few commandos left in the Highveld of the eastern Transvaal. Ben Viljoen was left in command of the area and given instructions to act decisively, which he did not do, handicapped as he was by difficulties with his subordinates. Botha made his way south, bypassing the yet-to-be-completed line of blockhouses and forts between Wakkerstroom and Piet Retief.

With only a few scattered commandos in the area, the most successful of the British column commanders, Colonel George Benson, made several raids into the Highveld in September and October. The area was practically swept clean of inhabitants and livestock and the fragmented commandos seemed to be keeping their distance.

Benson’s method of approach was to advance with a large column of more than 2 000 fighting men. The column was equipped for a long stay away from their base with wagons and carts, an infantry component and a strong contingent of mounted men. Some artillery completed the force, their function being solely to protect the nightly bivouac. With intelligence gained by black scouts, armed with a rifle and well-mounted, a strong mounted force would ride out at night and surround and attack the identified Boer laagers as dawn was breaking. The whereabouts of the laager would have been located by the scouts using their own knowledge of the area as well as intelligence obtained from the local black inhabitants. The raiders covered great distances, sometimes as much as 70 or 80 km from the main column.

The intelligence chief under Benson was Colonel Aubrey Wools Sampson, the former commanding officer of the Imperial Light Horse Regiment. Found wanting as a combat commander, Wools Sampson became the consummate intelligence officer by virtue of his knowledge of the local languages, Afrikaans as well as the Bantu tongues, and the topography. He had been involved in prospecting and mining in the Transvaal all his life, and a resident of Johannesburg in the last few years. A prominent British citizen, he was a member of the Reform Committee and his involvement in the abortive Jameson Raid had caused his arrest and imprisonment in 1896. He had refused to pay the fine and elected to serve sentence, but President Kruger ordered his release as a gesture of respect on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 (Amery, Vol 1, p 179).

Aubrey Wools Sampson

In 1901, raiding at night became standard procedure for the British columns engaged in locating and eliminating the scattered and elusive fragments of Boer commandos. The technique was very effective and most of Benson’s operations over the last few months were successful. His men captured more than 600 burgers, secured huge quantities of captured wagons and equipment, horses, herds of cattle and flocks of sheep.

The attack on Benson’s column

On 12 October, Benson went in to Middelburg to refit his column and exchange some of his units for fresh men. Some of the replacements had been engaged for some months in garrison duties and were not entirely conversant with Benson’s methods. He left with them on 20 October, heading towards Bethal. His column comprised 501 men of 3rd Mounted Infantry (MI) (King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry), 462 men of 25th MI (King’s Royal Rifles), 434 men of 2nd Scottish Horse, 82 men of 84th Battery RFA, 36 men of CC and R Sections Vickers-Maxims, and 650 2nd East Kents (‘The Buffs’), making a total of 2 165 fighting men. In addition, there must have been a considerable number of drivers and servants. Acting on intelligence, they raided a Boer laager at Klippoortjie. Thirty-seven Boers were captured, but there is confusion as to whether they were commandos or ‘joiners’, men who went over to the British side and acted as guides. In Ackermann (1969, p63, p87), they are first described as prisoners, then in a later reference, as National Scouts, Boers who acted as guides and scouts for the British Army. There were frequently Boer ‘joiners’ acting as guides in British columns but there is no specific mention of any in Benson’s column, who on this occasion suffered no casualties in fighting off a counter-attack by Boers who had recovered from the initial surprise of the raid at dawn.

By then, Botha’s raiders had returned from their unsuccessful foray into Natal. Most of the commandos had split into smaller detachments, as was their usual practice. Before he had left on the raid, Botha had sent the Transvaal government across the Pretoria–Delagoa Bay railway line and they were in relative safety near Roos Senekal. Now Botha and some of his men were at Schimmelhoek and the adjacent farm, Mooifontein, at Bakenkop, east of Ermelo. British intelligence had discerned their presence there from a document captured from a Boer rapportryer and Rawlinson’s and Rimington’s columns were sent from Standerton to descend on this sought-after quarry.

Boer scouts managed to decoy the two columns away, although Botha had a narrow escape galloping away to the north in such haste as to leave some of his papers and his hat in the Mooifontein farmhouse. This happened 25 October and, a few days later, gton and Rawlinson were back in Standerton and Volksrust. On that same day, Benson’s men had a sharp encounter with Boer commandos at Rietkuil, some distance north of Bethal. (A diary entry by Willie Wilsworth for 25 October describes an action but does not name a place. His grandson’s edit of the entry identifies it as Rietkuil. Ackermann, 1969, pp 66-7, describes an action around Ystervarkfontein and Mooifontein, north of Bethal.) Benson’s Australians in the 2nd Scottish Horse gave a good account of themselves against determined Boers on ridges along the Steenkool Spruit.

Botha’s return from his raid stiffened resistance with the instructions he had given that Benson’s column, isolated and alone on the Highveld, should be attacked with determination. Bethal (and Ermelo too) was in ruins and deserted, but British patrols met with unusually sharp resistance. Around Bethal, at Mooifontein and Kafferskraal (this offensive farm name appears on contemporary maps but has now been expunged from modern surveys), there were clashes. Benson’s camp at Kaffirstad (another offensive colonial name) was closely watched by Boer riders and Woolls Sampson was unable to conduct his usual scouting manoeuvres – it was inadvisable for his scouts to venture out. If captured, they would be shot out of hand.

Panorama looking north from Gun Hill.

(Photo: By courtesy, R Smith).

It was now obvious to Benson that he was in a position of some danger. He was isolated at a considerable distance from his base along the railway line to the north. Other columns were still making their way back from Natal, needing to rest their horses and replenish their supplies. In the event of a serious attack, relieving columns were too far away. It had been a risk to venture into the area, but with the better Boer fighting men away in Natal with Botha, it had seemed more of an opportunity than a risk. Botha and his commando leaders recognised that there was now a rare opportunity to strike at the lone column.

Normal Boer tactics were for the commandos to fragment into small entities. This way they could more easily evade the attention of the British columns, while it was always possible for them to re- converge for a concerted attack should the opportunity arise. Now was just such a time, and Botha returned to Schimmelhoek to give orders for his commandos to join him. He gathered together a force of 500 men from Carolina, Standerton and some of the Swaziland Police. Perhaps even more importantly, he had with him three generals who would be able to organise an attack on Benson’s column. They were Johan Grobler, Coen Britz and Koot Opperman, all of them experienced and aggressive leaders.

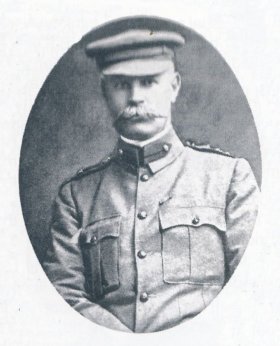

Coen Brits

Commandant Hans Grobler of Bethal, Piet Trichardt of Middelburg and Piet Viljoen of Heidelberg, with their commandos, had more than 700 men in the area around Bethal. They did not think themselves strong enough to launch an attack on Benson’s column without assistance. By 28 October, Botha, with reinforcements, was not far away, having spent that night at Vaalkop, north of Bethal, on the farm Elandsfontein. This was a place that the Boer commandos commonly used, for the hill offered sweeping views of the surrounding countryside and a site for a heliograph. Importantly, Grobler’s close surveillance of the British camp meant that Wools Sampson had been unable to conduct his usual scouting activities and the arrival of Botha’s force had remained undetected. Around 1 200 determined and well-mounted Boers were now in the vicinity.

Benson sent a runner to Brugspruit Station on the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay railway line, informing the army command that he was returning and that he would be there in a few days’ time. On 29 October, his column marched to Zwakfontein, where they camped overnight. This had good water supplies and must have resembled a small town that night with more than 2 000 soldiers and their artillery and wagons. Two soldiers are listed as wounded at Zwakfontein, so there were Boers close enough to snipe at them. Orders were that the march to the next camp would commence at 04.00. It rained during the night and it was misty in the early morning.

The going was tough after the overnight rain. The mule wagons and the marching infantry had no difficulty, but the heavily laden ox wagons moved slowly. There was only one stream of any significance to negotiate, the Dwars-in-die-Weg Spruit, which was probably running quite strongly. Right from the start, Boer commandos were visible on the flanks of the column, which was not unusual. What was less expected was that there were many more than normal and they seemed to be more aggressive. In the misty conditions during the early part of the march, they were able to get quite close. (The mist and rain in the morning cleared by midday, according to the entry for 30 October in the Wilsworth diary).

Because of the slow pace, the convoy became extended with the mule wagons getting to Nooitgedacht, where they were to make camp, as early as 09.00. All except one wagon made it through the spruit, some probably needing double spans to pull them out. One seriously bogged- down wagon resisted all efforts at extraction and had to be abandoned. It evidently contained foodstuffs of various sorts. (Ackermann, 1969, p85 quotes a Boer describing how he had found a bottle of wine, a pudding and some tinned food in the wagon).

The battle

The rear-guard had come under increasing fire as the Boers realised what had happened to slow down the British convoy. The officer in charge was Major Gore Anley of the Essex Regiment, with 180 men of the 3rd Mounted Infantry (King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry [KOYLI], Dublin Fusiliers and Loyal North Lancashires). In addition, there was infantry support with a few men of the East Kent Regiment and a pom-pom, quick-firing gun. Anley had sent word back to camp of his difficulty, abandoned the bogged-down wagon, and retired to the next rise.

The pom-pom came into action, but then jammed, and was sent into camp with a small escort. Benson himself then arrived with an escort of Scottish Horse and endorsed Anley’s decision to abandon the wagon. His orders at camp had been for defences to be set in strong picquets at intervals around the camp and on an arc of about 800 metres distance. In line with this and to protect the left flank of the convoy, two guns of the 84th Field Artillery Battery had unlimbered somewhat earlier on a rise, later to be known as Gun Hill. With them was an escort of the 25th MI (King’s Royal Rifles) under Sergeant Anfield.

Anley and his men were sent back to man one of the positions on the eastern perimeter of the defensive arc. Benson, with the Scottish Horse and the 3rd MI, then headed for Gun Hill. As they did so, a swarm of Boer riders appeared over the skyline to the south. Hidden in the folds of the ground, a large Boer force had concentrated, and Botha’s generals had deployed them into a long line that extended for nearly two kilometres. They saw their opportunity and charged towards Benson and his retiring men, overlapping them on both sides.

Several unmounted East Kents were overwhelmed in the charge, but the mounted men made it to the ridge where the guns were positioned. A defensive line was formed around the guns, which had to be held at all costs, the loss of a gun being unbearable for artillerymen! On Gun Hill were 180 men spread out on each side of the guns, Scottish Horse, a few East Kents, and KOYLI.

The left wing of the Boer charge continued onwards to attack a company of the 25th MI under Captain Crum, who were on a rocky outcropping to the north-west of Gun Hill. They were able to organise some rudimentary cover for themselves and had another of the 84th Battery’s guns. Benson, now in harm’s way, was unable to exercise central control over the fighting.

In the Nooitgedacht farmhouse were Colonel Woolls Sampson and Major Dauglish of the East Kents, the latter being the senior Imperial officer present. Woolls Sampson took command and Dauglish’s infantrymen threw up defenses and dug trenches. With the defenders spread around the camp in a wide arc, there were few men left to provide reinforcements for the defenders of Gun Hill.

On Gun Hill a close-range fight took place with the defenders, mostly the Australians of the Scottish Horse, King’s Royal Rifles and KOYLI. It was on Gun Hill that the Boers concentrated their efforts with the two guns as prizes. What use they would make of such weaponry is moot, since they were later discovered hidden away on the farm Kaffirstad (sic) in December. Almost all the defenders of Gun Hill were killed or wounded, and a few made their way back to camp.

Looting

Several accounts say that British wounded were stripped of their clothing and boots, despite orders from General Johan Grobler to his men that such behaviour would merit severe punishment. (Wilsworth’s diary entry for 27 October tells of a letter received from General Johan J N H Grobler after engagement at Rietkuil, stating that ‘[i]t has caused me great annoyance and displeasure, to see that some of my men stripped your wounded soldiers of their clothing, which was against all orders of my leaders and officers, and everything will be done to find the offenders, who will be severely punished.’ Only wounded men were left on the hill, including Benson with a mortal wound. There were enough of them still capable of driving away Boers looking for loot (Wilson, Vol II, pp 833-4 describes the looting and murder of wounded. Notwithstanding General Grobler’s letter, with clothing difficult to acquire it was difficult for Boers to ignore a uniform jacket or a fine pair of boots on one of their dead or wounded enemy soldiers).

Once the firing died down, the Boers took possession of the two guns on Gun Hill, swinging them around. It is possible that shots were fired at the camp. Ackermann (1969, p 80) says that artillerist Kotie Naudé was helped to turn the guns around and fired two shots at the camp. The first shot went way over the camp, but the second hit its target. According to E J Weeber’s account (1938), ‘among the burgers were a couple of ex-artillerymen who quickly took possession of the guns and turned them onto the centre (camp) of the enemy’. It is not known how many shots were fired. Once the Boers came over the crest of the hill, the artillery (which must have been the two guns in the outposts to the west) put down a rain of shrapnel which caused them to take cover once again.

At nightfall, ambulances came out from the camp to succour the wounded, Benson among them. He was taken back to camp and gave Wools Sampson orders for the camp to be held at all costs. He died at 06.00 the next morning. Amery (Vol V, pp 360-76) has a long and detailed account of the fighting and the individuals involved, different to the version told by Maurice (Vol IV, pp 304-15).

With the camp surrounded and numbers of their animals killed or taken by the Boers, the British were not in a happy position. The Boers made no attempt to assault the camp. A night attack would have been very hazardous, besides which they had insufficient manpower and no heavy guns of their own. It was said that Botha was reluctant to attack since the camp contained numbers of Boer women and children. There certainly were non-combatants in the camp, including the 37 captured men from Klippoortjie, mentioned above. As Bethal was deserted and most of the buildings destroyed, it seems doubtful that the column had made many captures during this foray. Ackermann (1969, p69) says that ‘all the old people, women and children who were still on the farms Rensburghoop, Witbank and Kafferstad were collected together’ and taken with the column. Blake (2012, p168) includes a quote about Boer civilians in the British camp, including, apparently, a Mrs Grobler, a relative of Commandant Hans Grobler.

Relief arrived on 1 November from Standerton, in the form of Allenby and de Lisle, and from Leeuwkop, east of Springs, with Barter. Maurice (Vol IV, p315) gives the strength of these columns as: Allenby, 1 288 mounted men and five guns; de Lisle, 1 004 mounted men and five guns; and Barter, 531 mounted men, 762 infantry and five guns. One of Kitchener’s senior staff officers, Colonel Gilbert Hamilton, took command of what was by then practically a force of brigade strength in the area.

Map of the Battle of Bakenlaagte, 30 October 1901,

transposed onto a modern 1:50k topographical map.

Botha did not attempt to press home his advantage and merely complimented his men on their courageous conduct, returning to the east and the Schimmelhoek farmhouse. The Boer commandos once again scattered into their various sanctuaries.

The cost

Kitchener, in Pretoria, was somewhat disheartened by the setback to Benson’s column and wrote to Secretary of State for War, St John Brodrick (letter of 1 November 1901, quoted in Pakenham, 1979, p 536) that ‘[t]he Boers observe the movements of a column from a long way off, then having chosen some advantage, in this case it was the weather, charge in with great boldness, and the result is a serious casualty list.’

Bakenlaagte was not an overwhelming victory for the Boers, although the British loss of more than eighty killed in action and died of wounds and two guns was certainly an unwelcome setback. After two years in the field, the Boers were clearly not yet beaten. Their own loss of more than sixty experienced fighting men who were irreplaceable, was a serious blow. Blake (2012, p173) comments that, on the Boer side, Bakenlaagte is mistakenly held up to be a famous and complete victory, especially to promote nationalism: ‘Aan Boerekant, weer, is Bakenlaagte verkeerdelik as ‘n roemryke en volkome oorwinning voorgehou, veral,om nasionalisme to voed.’

Command in the eastern Transvaal was now given to Major-General Bruce Hamilton, another of the younger, more vigorous leaders. In this revitalized campaign, Botha and his staff had some narrow escapes from capture until they were driven into the mountains north of Vryheid. Bruce Hamilton, in command in Vryheid, was ordered not to engage in active operations against the Boer commandos known to be in the area. The war was not yet over, but both sides were now making overtures of peace.

| Casualties - British fatalities (88) | |

|---|---|

| Died of wounds | 18 |

| Died by accident | 8 |

| Killed in action | 62 |

| Regiment: | No of fatalities |

| Cheshire Regiment | 1 |

| Coldstream Guards | 1 |

| East Kent | 10 |

| King’s Royal Rifles | 15 |

| Loyal North Lancashire | 1 |

| Northumberland Fusiliers | 1 |

| Royal Dublin Fusiliers | 1 |

| Royal Artillery | 1 |

| Royal Field Artillery | 10 |

| Scottish Horse | 33 |

| Seaforth Highlanders | 1 |

| Yorkshire Light Infantry | 13 |

Casualties - Boer fatalities (63)

Killed in action or died of wounds.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org