The South African

The South African

Introduction

April 22, 2019 is the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Graham's Town, then a small hamlet of probably no more than 30 simple buildings. In the major encounter of the Fifth Frontier War, a small British force defended itself against an army of the amaNdlambe clan and some minor allies, eighteen times its size. This was arguably one of the most decisive battles in South African history, along with Blaauwberg and Blood River/Ncome, as it altered the course of events and the political geography during the nineteenth century.

Two major factors impinge on any description and understanding of this battle: Firstly, the paucity of reliable source material, particularly primary sources; and, secondly, the considerable amount of writing (over 40 publications) which constitutes the secondary sources available. Much of the latter is contradictory, over-imaginative, or very close to fiction. This account of the battle has accordingly drawn only on primary or substantiated secondary sources. Strictly-speaking, there are only two primary sources on the battle itself, both written by the British commanding officer, Lt Col Thomas Willshire: viz. his 1819 despatch to the Governor, Lord Charles Somerset, and his 1846 article in the Graham's Town Journal, which are virtually identical. The much quoted 1876 article by C L Stretch is neither a primary source nor always reliable. Stretch relied on the hearsay of others, some of which was false information. He was neither present at the battle nor ever personally claimed he was, although he was in Graham's Town a few days later. This article accordingly places the greatest value on Willshire's account, backed-up by that of Major George Fraser in a letter to Col John Graham the day after the battle, a hybrid source. All quotations are from Willshire's 1846 article, p 2, unless stated otherwise.

Circumstances leading to the battle

The detailed reasons for the amaNdlambe attack on the British military headquarters at Graham's Town are beyond the scope of this article, but they boil down to long-simmering tensions on the Eastern Cape frontier (Cory, 1910; Scott, 1973; Milton 1983; Peires, 2001). These involved extensive cattle theft, raids and counter-raids across the border, at that time the Great Fish River, as well as internecine struggles within the amaXhosa polity. This animosity was primarily between Ngqika, the young senior chief of the amaRharabe (a major branch of the amaXhosa people) and his aged uncle, Ndlambe, who had acted as regent until Ngqika became of age. The antagonism between them was both political and personal, involving power and jealousy. While the majority of the clan appears to have supported Ndlambe, the governor, Lord Charles Somerset, had, shortsightedly in retrospect, allied the British with Ngqika.

After a major battle at Amalinde in October 1818, when Ngqika's forces had suffered a major military defeat at the hands of Ndlambe (Herbst & Kopke, 2006), Ngqika appealed to his British allies for help. This was forthcoming in the form of a major British-amaNgqika raid into amaNdlambe territory in early December 1818, which left many of the amaXhosa east of the Fish River impoverished. The amaNdlambe were quick to retaliate and invaded the colony in late December 1818. This precipitated the Fifth Frontier War, resulting in widespread destruction of property and loss of life. The British and colonial authorities then began to build up forces for a major punitive expedition, a point not lost on the amaNdlambe.

Implicated in all this was a politically astute mystic, Nxele, also known as Makana. Although a commoner, he had a wide following and was an influential councillor to Ndlambe. He was also well known to both missionaries and the military, among whom his agile mind and debating skills were recognised. The details of his involvement and the role he played in planning the attack on Graham's Town are not clear, although, as a war doctor and mystic, it would probably have been significant. Most writers, and certainly the British, believed he was the mastermind behind the attack and had orchestrated both it and the general invasion which preceded it.

Prelude to the battle

The attack on Graham's Town began to take form at mid-morning on 22 April 1819. The amaNdlambe had, in the preceding days, managed to assemble an army of several thousand warriors within 10km of the settlement without the British being aware of it. At about 10h30, Lt Col Willshire, newly arrived on the frontier, was inspecting the Cape Regiment (CR) troop of mounted infantry when he received a report of cattle being taken nearby. Accompanied by 25 members of the troop, he went to investigate, pursuing the perpetrators some distance before coming across a body of 200 to 300 warriors who then retreated. Following them, he realised that they were attempting to lead him into a trap and surround him. Willshire attempted to retreat but was surprised to come upon the entire amaNdlambe army, which he estimated at 5 000. He concluded that they intended to attack Graham's Town and, after sending a message to his second-incommand, Capt Trappes, warning him of an impending attack, he and his party tried unsuccessfully to delay the advancing force as they made their escape.

As Willshire reached the town at about 11 h45, the amaNdlambe army appeared on the hills and ridges to the east of it, about 2km distant. Although they may have had the opportunity of immediately surprising and overwhelming the town, the attack was delayed for nearly two hours while, according to tradition, various rituals were conducted, and final arrangements made. This delay allowed the defenders time to deploy their forces and prepare for the attack.

The battle

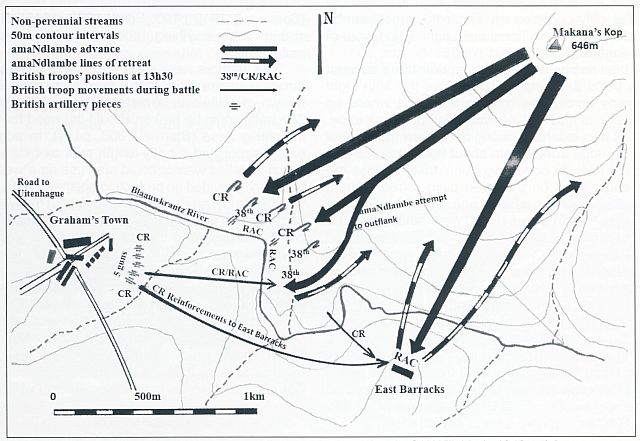

The geography of the battlefield is such that, on the eastern side of what was the edge of the village, a gentle slope leads to a small stream known as the Blaauwkrantz River. On the other side of the stream is a plain, where Willshire deployed his forces. Two and a half kilometres to the east of the stream, the plain gives way to a ridge, the most prominent feature of which is a knoll, now known as Makana's Kop. This is where the amaNdlambe massed before the attack. This was the only set-piece battle of the East Cape Frontier Wars before 1850 and the only occasion on which the amaNdlambe abandoned their traditional bush-fighting in favour of open warfare (Peires, 1981 p143).

As best can be discerned from Willshire's accpunt of his troop deployment, he pushed the 38th Light Company across the river to the point where he expected the thrust of the amaNdlambe attack to be. The CR was extended 'along and below the point of a gentle slope from a plain about 800 yards (731 m) from the town to cover two guns taken across the river and placed on the open plain in rear of and above the mounted infantry and the 38th. Parts of the Royal African Corps (RAC) were sent across the river 'to remain in support of the guns and extended troops' (see Figure 1 - Map). Willshire states that he 'therefore left five pieces of artillery at the end of town' so that 'as soon as we descended [i.e. retreated] from the plain into the ravine [donga] to re-cross, those guns would have the [enemy] open to them all across the plain if they followed us'. The CR infantry were kept 'in reserve for those guns in the event of any attack being made on the town from another point'. About 2km downstream from the position occupied by the 38th were the East Barracks, home of the CR. Sixty RAC troops were sent to defend them.

Willshire estimated that the amaNdlambe force was not in excess of 6 000 warriors, although most writers of secondary sources place it much higher. Stretch (1876) for example gives a figure of 9 000. In his report to Earl Bathurst, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Somerset boosted the figure to at least 10 000, almost certainly as leverage for obtaining more British troops for the colony (Somerset, 1819 p193; Scott, 1973, p118). Fraser stated that anything above 5 000 was an exaggeration.

Figure 1: A conjectural map of the battle,

based on Lt Col Willshire's 1846 article.

The warriors were each armed with eight to ten throwing spears, which had a maximum range, if well thrown, of a little over 60 metres (Tylden, 1952, p136). The hafts could be broken should the need for close in-fighting arise (Barrow, 1806, p414). In addition, each warrior had a body-length oval ox-hide shield which a skilled warrior could also use as a weapon, but which provided no protection against bullets. Both Willshire and Fraser claim that several of the warriors had muskets which, if they did, would probably have been obtained from traders or deserters. Willshire also makes a passing reference to 'a deserter' assisting them, which Somerset translates into 'the plan was formed and directed by certain deserters of the [Royal] African Corps' (Somerset, 1819, p201). They were under the overall command of either Makana or Mdushane, the eldest son of Ndlambe, which would have been the tradition. Historical records, such as they are, are ambiguous about this. Sources also vary as to who was leading which part of the battle.

There were 333 armed men defending the village, composed as indicated in Table 1. All were under the overall command of Lt-Col Willshire, OC of the 38th Regiment of Foot. He was regarded as a strict, but fair and highly capable officer, known to his men as 'Tiger Tom'.

| Table 1: Forces defending Grahamstown: 22 April 1819 | |

|---|---|

| Royal African Corps* | 135 |

| Cape Regiment ** | 121 |

| 38th Regt of Foot - Light Company + | 45 |

| Armed men unattached § | 32 |

| TOTAL | 333++ |

The weaponry available to the British forces consisted of the Long Land Pattern flint-lock musket known as the 'Brown Bess', which had a 15-inch bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting. Its effective range was about 70 metres (Tylden, 1952, p136) and a well-trained soldier could fire two to three shots a minute, though not for continuous periods. Willshire is obscure on the artillery which he had available. His descriptions have been variously read as between three and seven pieces. Tylden (1952, p136) suggests five, possibly a combination of 3-pdrs and 6-pdrs, under the command of an officer of the Royal Artillery. It is nowhere stated who actually manned the guns during the battle.

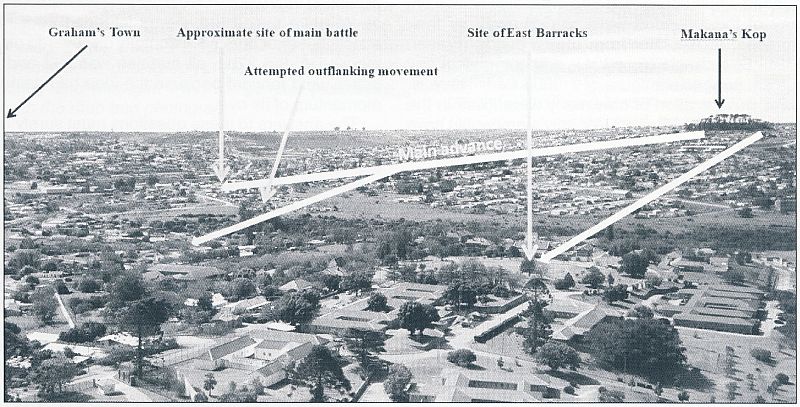

When the amaNdlambe advanced down the hill onto the plains below at 13h30, they were organised into three divisions: about 1 000 warriors had been sent to attack the East Barracks and the other two divisions launched a frontal assault on the eastern side of town itself, apparently where Willshire had expected them to. (See Figure 2 oblique photograph of the battlefield.)

Willshire then directed his troops to advance and open fire on those in front to induce the mass of warriors to move down to their support and get them within the range of the two artillery pieces placed across the river. Amidst war cries they 'rushed down to the troops, a short distance, in masses and then spread into clouds covering the hill as they ran.' Willshire describes this charge in terms such as 'a most determined and wellarranged attack'. The amaNdlambe came to within 30-35 yards (28-32 metres) of the troops who only then retaliated with disciplined volley fire from the muskets and probably case-shot or canister from the artillery.

Willshire records that he saw 'immense numbers' trying to outflank him (a classic amaXhosa tactic) to the right of the 38th and that he moved the RAC from reserve, bringing them forward into line with the 38th and the CR's mounted infantry, from where they opened 'a well-directed fire and completely stopped [them] from proceeding though they would not retreat till I ordered the advance to sound, when the soldiers cheered, and strange to say, [the amaNdlambe] began retreating pursued by the troops: but they ran so excessively fast that the men were not able to keep up with them'. Not wishing to be outflanked and wary of an amaNdlambe reserve rushing to get in their rear, Willshire sounded the retreat and brought his troops back to where the guns were. Of the amaNdlambe he remarks that their determination 'to do as much mischief as possible was wonderful'.

There is no indication of any close-quarter fighting taking place in the direct attack on the town, the disciplined volleys of musket fire and probably the. cannons keeping the amaNdlambe at a distance. These warriors never got to use their spears, although there were unconfirmed reports that, after the battle, many were found with their hafts broken in anticipation of hand-to-hand combat. According to Fraser (1952 p139), many dead warriors were also found with their full complement of spears still clutched in their right hands. The reports nevertheless suggest that the defenders were hard-pressed.

Willshire does not give any details of the fighting at the East Barracks, but Fraser states that the fighting was fierce, some warriors even getting into the barracks square which suggests that there would have been some hand-to-hand fighting. Neither Willshire nor Fraser mention a hunter named Boesak possibly intervening in the battle, as alleged by Stretch and some subsequent writers.

At around 15h00 the rank and file of the amaNdlambe began to waver and lose their determination, and then to retreat, thus turning the tide of battle. Initially this was in the main attack while 'the firing still continued at the barracks.' Soon after, it seems that the attackers at the East Barracks also withdrew. By 15h30, says Willshire, the amaNdlambe 'were beaten in every direction and retreated.' Whether this was by command or by recognition that with mounting losses they were making no headway, or by a spontaneous sense of defeat, the records make no comment and we have no idea. There was no pursuit due to a lack of cavalry and horses.

There are, however, disagreements about the circumstances of the withdrawal. Stretch, and those who copy him, claim that it was a rout. Neither Willshire nor Fraser concur with this. Quite the contrary, it appears that it was sufficiently orderly for the amaNdlambe to make off with 1 000 head of cattle, mainly those belonging to the CR soldiers, a point bemoaned by Fraser, an officer in the regiment (Fraser,1819, p140; Malherbe, 2012, p78). Moreover, Willshire, presumably expecting a counter attack, only withdrew into the town at dusk where he 'placed the troops and guns at the necessary points for its defence, and who remained at their arms all night'. No further attack came although the British forces were on edge for days afterwards.

Figure 2: An oblique aerial photograph showing the slopes

down which the amaNdlambe attacked and retreated.

Casualties

Among the defenders of Graham's Town, casualties were minimal, probably all incurred at the East Barracks. All accounts agree with the official figure, which gives three killed (two CR men and one RAC man) and five wounded. Eight others, including a woman and child, five soldiers and a herdsman were killed in the vicinity of Graham's Town on the day of the battle (Fraser, p141).

The amaNdlambe casualties of the battle are difficult to determine with any accuracy as the accounts vary widely, particularly those given for the number killed. Willshire (in Somerset, 1819) reports between 700 and 800 killed and an unknown number wounded - numbers which Somerset also settles on. Many of the wounded were carried away by their comrades, to die later from their wounds (Fraser, p139). Stretch (1876, p301), without giving any sources, suggests a figure of 2 000 killed. There is, in fact, no indication of how many were killed in the fighting at the East Barracks or how many would have succumbed to the artillery and sustained musket volleys at the main point of battle.

The site of the battle is still relatively easy to recognise today. Even though it has been largely built over in recent years, the general course of the battle may be observed from several points in and around Grahamstown. The isiXhosa appellation for the battlefield in the vicinity of the East Barracks is Egazini (The Place of Blood), but it is not clear when this name would have been given to it as there were no amaNdlambe nor any other isiXhosa-speaking people living in the area at the time. There are three monuments commemorating the battle in the city.

Makana surrendered himself to the British some two months after the battle and was exiled to Robben Island (Stockenströ6m, 1887, pp121-122). He drowned in December 1819 while attempting to escape. Willshire, after a successful career in the army, died a general in 1862 at the age of 73. Mdushane became Chief of the amaNdlambe after the death of his father at the age of over 90 in 1828.

Evaluation of the battle

From the amaNdlambe point of view, attacking the British military headquarters made strategic good sense. In the bigger picture of the Fifth Frontier War, it is also quite possible that the attack was conceived as a pre-emptive strike occasioned by the build-up of colonial forces as the war had been going on at a relatively low-key level for some months. Had they been able to obliterate the British garrison at Graham's Town, the eastern Cape would have been open to invasion as far west as George and perhaps beyond. It is at the tactical level that the amaNdlambe endeavour failed. It was the one opportunity they and their allies had of politically and militarily dominating the area. The major question begging to be asked is why, notwithstanding the technological disparity in weaponry, the amaNdlambe lost the battle with the numerical odds stacked so much in their favour. The reasons for this are complex.

Why, it may be asked, were there no attempts to surround the town and subject it to a multi-pronged attack, rather than attacking muskets and cannons head on, over open ground in broad daylight? By virtue of their numbers, the amaNdlambe should not have lost the battle. This was not their first encounter with the weaponry they faced and they must have been aware of the devastating effect of such weapons. In addition, there is consensus that they had detailed intelligence, gathered by both Makana himself and the spy Nguka, of the garrison's capacity to defend itself. Was it over-confidence in the medicine of the war doctors or was it arrogance, assuming they would have a walk-over? Perhaps too, as Willshire suggested, it was intended as a night attack, but after being accidentally discovered on the morning of the 22nd, all surprise was lost and the attack went forward because the idea had gained a momentum of its own.

The answers to these questions must surely lie in part on poor and inept leadership and for this Makana, the apparent overall leader, must be held largely responsible. Historically, mystics and prophets have made poor generals, commanders and captains, and their followers have paid in blood, often heavily. The battle of Graham's Town in 1819 was no exception.

The descriptions of the defence available, suggest that it was steady but not heroic. Nevertheless, Willshire described the result of the battle as 'close' and was quoted by Stretch as saying at a dinner a few nights afterwards that at one period of the fight 'he would not have given a feather for the safety of the town .... ' (Stretch, 1876, p301).

Conclusion

On the outcome of the battle, Tylden (1952, p135) has posited that it was the first occasion in South Africa in which a handful of individuals repulsed superior numbers relying on the arme blanche, with insignificant loss to the defending side. He argues, too, that it not only influenced future eastern Cape Frontier tactics, but set the pattern for many of the military encounters of the Great Trek.

To get some perspective on the scale of this event, we might note that it ranks low in the annals of British military history, receiving only seven lines in Fortescue's definitive History of the British Army (Fortescue, 1923, p394). Some historians have dismissed it as no more than a major skirmish. In the South African context, however, the result had long-term consequences, not only for Britain's recently acquired Cape Colony and the future of its eastern border region, but for the general westward migration of the isiXhosa-speaking clans. Had Makana and his amaNdlambe won the day, which they should have, it is possible that other clans may have joined them in a great sweep well beyond the village and fort at Algoa Bay as had occurred previously in the Third Frontier War. The semiitinerant Trekboers in the area may finally have abandoned the volatile frontier zone and the Great Trek might have taken place earlier than it did, with unknown consequences. In such an event the British authorities in the Cape Colony may have decided to reconquer the territory but might equally have decided to abandon it as an unnecessary expense with little or no return. Willshire (1846, p2) himself mentions the likely loss of the frontier under such circumstances. In either event there would have been no British settlers arriving in the Eastern Cape in 1820, and the history of the area would have been entirely different. In terms of South African history, it was a decisive battle.

Author's acknowledgements

I wish to thank my wife, Anne, and son Michael, for critical comments on the text and for proofreading. I also thank Sean Pennefather for taking the oblique aerial photograph of the battlefield area and Barry and Morrigan Irwin for general assistance with the map and photograph.

REFERENCES

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org