The South African

The South African

Rhyme from contemporary newspaper in Umtali (now Mutare)

As many as 20 000 Australians fought in the AngloBoer War of 1899 to 1902. When the population of Australia was little more than 3 500 000, a total of 16 175 volunteers were accepted to fight in South Africa. The services of as many again were turned down. Unsuccessful applicants, in considerable numbers, made their way to the Cape and Natal to join the ranks of the colonial forces. All the volunteer regiments from the Cape Colony and Natal had large numbers of Australians in their ranks. This was due to the influx of Australians who, in pre-war days, had lived and worked in South Africa. Public opinion supported the policy of the various colonial governments to show loyalty to Britain, their mother country. The first contingents offered were little more than a token effort. Most Australians thought that the 1 200 men who sailed into the Indian Ocean in the first convoy on their way to the Cape would have little direct military effect. (Details of all those who served in the Anglo-Boer War in contingents from the various states are detailed in Murray Official Records of the Australian Military Contingents to the War in South Africa).

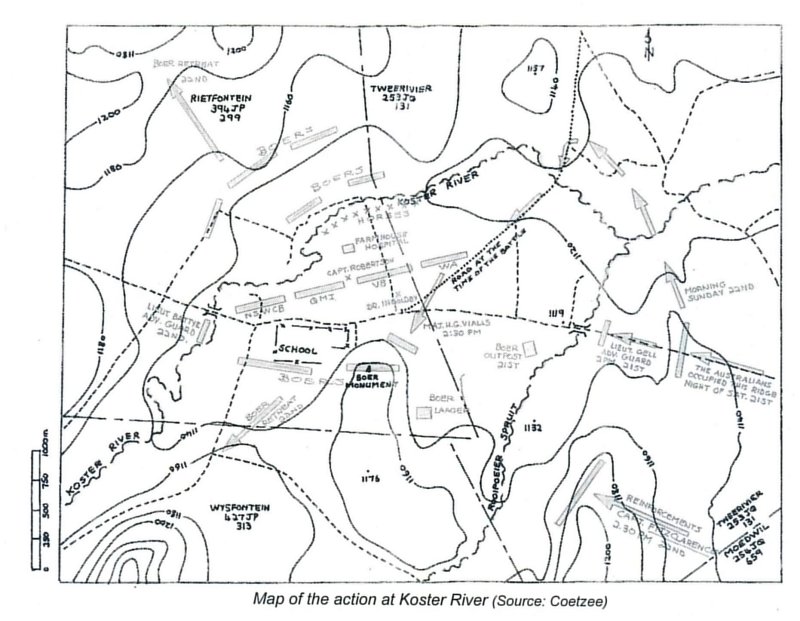

Map of the action at Koster River (Source: Coetzee)

British reverses at Colenso, Magersfontein and Stormberg in December 1899 'stirred the Australian and New Zealand colonies to a fresh pitch of patriotic fervour' (Wallace, 1976, p231). Second contingents were raised, like the first, from the militia army regiments of the various colonial governments. The Imperial Government was now expressing a preference for mounted men rather than infantry. However, an idea was mooted in Sydney for a force of 500 Bushmen, sponsored by public subscription, to be sent to the war. 'It supported the widespread belief that ... stockmen and drovers, with a background and training ... similar to the Boers themselves .. .' could well match the Boers in the irregular warfare that was now being waged (Wallace, 1976, p 232).

The Bushmen

Impressive sums were soon raised from all sections of the community and there was 'a rush to enlist despite warnings that only genuine bushmen need apply'. Their abilities were tested and the average age of the Bushmen was higher than that of the earlier contingents, reflecting the selection of only experienced rural men. In eleven weeks, 1 400 men around Australia were enlisted, drilled and equipped in what were Citizen's Bushmen units, one squadron each from South and Western Australia, two each from Victoria and Queensland, four from New South Wales and half a squadron from Tasmania. Only those from New South Wales used the designation 'Citizen Bushmen'. (On the day that most of these Citizen Bushmen were embarking, the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, telegraphed to the Premier of New South Wales, asking for a further 2 000 men of the same class as the Bushmen. They were required for general service in South Africa and the British Government undertook to bear all the costs of raising and sending the force. These were the Imperial Bushmen Contingents, better trained and disciplined than the Citizen's Bushmen units and raised in all six colonies (See Wilcox, 2002, p38).

There were very few suitable officers; almost no Australian had lived in the bush and commanded soldiers in wartime. The New South Wales commandant, Major-General George French, chose Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Airey to command their contingent. Airey was an artilleryman nearly 60 years of age, but with service in India and Burma. From Western Australia, Major Harry Vialls was appointed, 40 years of age and with service in India and Afghanistan. The South Australian commander was Samuel H¨bbe, who had once commanded a militia unit. However, he also had bush experience, having been traversing dry, central Australia for the previous thirty years, finding routes and clearing land (Wilcox, 2002, p36).

About 1 100 men embarked at the various Australian ports. The transports with the Citizens' Bushmen arrived in Cape Town early in April. After spending the better part of a month in the cramped conditions of the troopships, they did not disembark in Cape Town, but were sent on to Beira in Portuguese East Africa.

On 17 May 1900, the Boer siege of Mafeking (today Mahikeng) was relieved by British forces coming from Rhodesia and a column from Kimberley to the south. The column from the south, under the command of Colonel Bryon Mahon, consisted mostly of horsemen, the Imperial Light Horse and the Kimberley Mounted Corps. Infantry, only 100 of them divided evenly between fusilier regiments from England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales, rode on the 60 mule wagons comprising the transport. 'M' Battery of the Royal Horse Artillery made up the balance of a powerful, mobile flying column, altogether about 1,100 men (Times History, Vol IV, p216).

From the north came Colonel H C 0 Plumer with a column hastily put together from the meagre forces in Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe), less than 500 men. They were mostly policemen of the BSAP (British South Africa Police) and soldiers of the Rhodesia Regiment, together with some untrained Southern Rhodesian Volunteers. They had tried to relieve the beleaguered town before Mahon's column had arrived, but were driven back by the Boers (Wilson, Vol II, p 593). On 14 May some welcome reinforcements arrived from Bulawayo in the form of 100 men of the 3rd Queensland Mounted Rifles, escorting four guns of 'C' Battery of the Royal Canadian Artillery (Miller, 1993, pp 181-4). Three days later the combined columns drove away the Boer besiegers and the longest siege of the war was at an end. After the town was relieved, numbers of Australian Bushmen units arrived down the railway from Rhodesia.

KOSTER RIVER (JULY 1900)

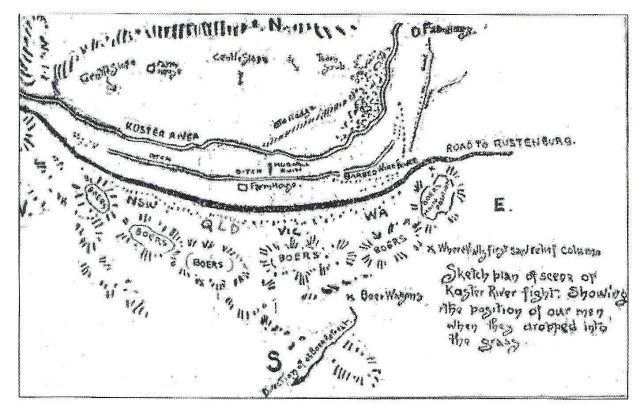

Sketch map (Source: Chamberlain and Drooglever, 2003).

The Rhodesians

There had been a threatened Boer invasion of Rhodesia in the early months of the war. However, Plumer's operations in the Tuli Block had resulted in the Boer commandos being withdrawn (Burrell, 2009). Plumer moved down with what forces could be spared from Rhodesia and was tasked with an attempt to relieve Mafeking. The Australian Bushmen Contingents and a Canadian artillery battery were intended to be reinforcements for Plumer.

At that time, with Kimberley still besieged, the only way for them to get to Mafeking was through Rhodesia and along the railway line which ran down the eastern side of Bechuanaland .

Arrival of the Australian contingents

The voyage to Beira went well and, by 11 April, four ships carrying the Australian volunteers were anchored off the port. The British government had negotiated with the Portuguese to use the port to enable men and materials to be sent across their territory into Rhodesia. Beira, at that time, was a fairly new town with buildings mostly constructed of corrugated iron. According to Australian Nursing Sister, Isobel Ivey (quoted in Wallace, 1976, p237), the Portuguese administration welcomed the men with a reception and a garden party for the officers and a ball that night. There were twelve hotels and bars in Beira, the venue of frequent rollicking impromptu concerts.

Major-General Sir Frederick Carrington arrived from England at the same time to take command of the Rhodesian Field Force. He was a soldier with great experience in southern Africa, from the wars in the Transkei, the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 and Warren's expedition to Bechuanaland in 1884-85. In 1893 and 1896 he had command of the forces in Rhodesia during the troubles with the Matabele.

From Beira to Rhodesia was a railway of sorts, one section having a gauge of 2ft 6ins, served by only six locomotives. It took some considerable time before all the Bushmen were transported the 350 miles (563 km) to Marandellas in Rhodesia. The climate of the Portuguese coastal strip was unhealthy for men and horses and there were heavy losses from malaria and horse sickness. The Canadians and their four guns were a priority and so they, together with the 3rd Queensland Mounted Infantry and the New South Wales Citizen Bushmen and their officers were the first ones to reach the Marandellas rail terminus on 20 April (Harvey, 1994, p 50). (Although designated as Mounted Infantry, the 3rd Queensland were recruited as, and referred to, as Bushmen. This is according to Harvey (1994, p 47)).

The journey of the Canadian artillery battery, accompanied by 100 dismounted troopers of the 3rd Queenslanders under the command of Major C W Kellie, was continued to Bulawayo by stagecoach drawn by mules. The next leg to Mafeking was by ran, with a great sendoff from Bulawayo - 'the whole town turned out to see us off, and we were escorted to the train by the Police band' (Harvey, 1994, p 52). They were in Ootsie, north of Mafeking, as far as the train would go, on Friday, 11 May, and marched the final 80 miles (129 km) to Plumer's camp. Advancing with Plumer and Mahon the Queenslanders and Canadians then took part in the operations leading to the relief of Mafeking on 17 May (Harvey, 1994, p 53).

Once Mafeking was relieved, Colonel Plumer led a composite colonial force to Zeerust, about 30 miles (48 km) inside the Transvaal border. The town surrendered without a fight and various Bushmen units kept arriving from Bulawayo, the New South Wales Citizen unit narrowly missing the entry into Mafeking with the relief force. Colonel Robert Baden-Powell marched into the Transvaal and by 14 June was in Rustenburg. Pretoria fell to Lord Roberts on 5 June and a week later the Boers were driven away from the east of Pretoria after the battle of Diamond Hill.

In the western Transvaal, all seemed quiet and peaceful. The Bushmen swept through the country east of Zeerust and, with the fall of Pretoria, the burghers seemed to be more than willing to lay down their arms. Captain J F Thomas, a small-town lawyer from Tenterden in New South Wales and later the defence lawyer for 'Breaker' Morant, said that: 'For the most part [the burghers] seem to be heartily glad that the war is drawing to a close, and that they are back on their farms again. But I fear that nothing like the proper number of Mauser rifles are handed in. There are Martini-Henrys, Westley-Richards and other out-ofdate weapons, even old flint-locks, but the much-prized Mausers are far scarcer than they should be' (quoted in Wallace, 1992, p 10).

Rustenburg

Lord Roberts now believed the west to be thoroughly pacified and ordered Baden-Powell to make a sweep north of Pretoria along the railway line. The only British presence in Rustenburg was the BSA Police under Lieutenant-Colonel C O Hore and a few New South Wales Bushmen. The presence of so few troops was interpreted by the citizens of Rustenburg as a sign of the direct intervention of the Almighty in response to their prayers. In the Dutch Reformed Church, the text of the service was: 'Wait patiently for the Lord, who will shortly drive out your enemies from amongst you' (quoted in Wallace, 1992, p13).

With the area pacified, it seemed that a supply route could be established from the railway at Mafeking via Zeerust and the drifts over the Elands River to Rustenburg. At the drift over the Elands River, there was just a store in 1900; the small town of Swartruggens came much later. On high rising ground to the east, a fortified depot was established with a good commanding position of the surrounding country.

There was a Boer krygsraad at Balmoral after the reverse at Diamond Hill and Botha instructed General Hermanus Lemmer to head back to Rustenburg and persuade the burghers in the districts of Lichtenburg, Marico and Rustenburg to leave their farms and return to the commandos. On his way there, Lemmer fell in with the small remnant of 130 Rustenburgers under Commandant Caspar du Plessis. On 3 July, Baden-Powell, now at the British base of Rietfontein, north-west of Krugersdorp, ordered the New South Wales Bushmen to retire to Zeerust. The Union Jack still flew from the Landdrost's office as the column with 40 wagons left Rustenburg in a severe thunderstorm on 5 . July (Wallace, 1992, p 17). Only 60 policemen were left there, under the command of Major A H C Hanbury-Tracy, which Lemmer immediately saw as an opportunity to recapture the town.

Lemmer had had some difficulty with those Rustenburgers who had signed the oath of neutrality with the British and were sitting on their farms. He was unsuccessful in his attempts to recruit more men from those who had already decided to surrender. 'All through the war the Rustenburgers had been somewhat refractory material' (Smuts, 1994, p93). On 7 July, Lemmer nevertheless called on Hanbury-Tracy to surrender, even though he had but a small group of men under his command. The New South Wales Bushmen were nearing Zeerust when the call came for them to render assistance back in Rustenburg. They arrived back there in time to drive the Boers away with Commandant du Plessis being killed and five Boers taken prisoner, all with British protection passes in their pockets. Major Weston-Jarvis of the Rhodesia Regiment said, 'I hope to goodness that they will shoot the lot ... it would stop the nonsense once and for all' (Wallace, 1992, p 19).

As a result of this attack, Baden-Powell arrived back in Rustenburg with a force of 1 500 men. General Koos de la Rey, whom Commandant-General Louis Botha had put in command of the western Transvaal, followed Lemmer westwards. He had only a small number of men with him but, together with Commandant P F Coetzee's 300 men, they overwhelmed the British defenders of Zilikaat's Nek on 11 July. A squadron of the Scots Greys and 84 men of the Lincolnshire Regiment surrendered (Maurice, Vol III, p 240). The Boer victory, 'although not very important in itself' (Smuts, 1994, p92) had the effect of convincing large numbers of Boers that, having sinned by signing the British oath of allegiance, their 'only true repentance was to violate that sinful oath (Smuts, 1994, p 86) and go back on commando. Within weeks, there were commandos forming all over the western Transvaal. (One source says that soon there were 'no less than 7 000 in the field' but gives no source. See Wallace, 1992, p 14).

Lemmer's men now occupied Olifants Nek after his abortive attempt to occupy Rustenburg. He was driven away by a column under Lieutenant-General Lord Methuen, assisted by Baden-Powell coming from Rustenburg on 21 July. Lemmer himself moved to the west and laagered on the farm Woodstock. There he was engaged in what he had been sent to the western Transvaal to do - to encourage the burghers in the district to rejoin their commandos. Some of his men were sent to occupy positions which commanded the road from Rustenburg to Zeerust. At Elands River a number of supply convoys now were unable to proceed any further. This was the main supply route to Rustenburg and stocks were low. The Boers had cut the telegraph line and the smoky atmosphere from grass fires made heliograph communication very difficult.

Two Rhodesian Regiment cyclists had made their way, unmolested, from Elands River to Rustenburg at about this time. The decision was therefore taken to send 150 loaded wagons along that road on 17 July. The Elands River garrison had an anxious wait to hear whether the convoy had arrived safely and it is a mystery why there was no interference from the Boers. Wallace (1992, p29) suggests that 'the timing ... of the uncontested passage coincided with some difference of opinion among the commandants.' On 20 July, two men, Troopers MacDonald and Albert Gould, set out at midnight with despatches for Baden-Powell. The bicycles were camouflaged so that nothing bright would glint in the bright moonlight. At Koster River the Boers had lit fires in a big laager off the road on the far side of the drift. The two cyclists paddled across the river and continued forward, only to be forced off the road by another group of Boers. They passed through Magato Nek, occupied by fellow Bushmen, and arrived in Rustenburg in time for breakfast. (The account of the two cyclists is told in A S Hickman, Rhodesia Served the Queen, and is quoted in Wallace, 1992, p 31. Baden-Powell issued a Special General Order commending the 'gallant conduct of Troopers McDonald and Gould ...' ).

The clash at Koster River

The two cyclists having located the Boer laager, Baden-Powell issued orders for a force of Bushmen to clear the road from Elands River. Supplies and a garrison had been building up there, unable to continue along the road to Rustenburg. Three hundred men of the Australian Bushmen contingents, comprising men from New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia, were sent back along the road to clear Lemmer's men away. The Bushmen had seen little action up to then. Wilcox (2002, p 109) writes that '[f]our squadrons strong, no regular officer in command, (;10 regular troops to slow them down - here was the Bushmen's chance to teach the Boers how to ride and shoot. '

They set off in the dark on the evening of 21 July, somewhat sullen that they were missing their sleep and covered the eight miles (12.8 km) from Mogato Nek in about four hours. Colonel Henry Airey was in command with Lieutenant-Colonel Holdsworth, a 7th Hussars officer on special service in Rhodesia, as his second-incommand. They were required to bring in a convoy from Elands River after they had dealt with the Boers. The advance guard, some distance in front of the rest of the column, was fired on as they came over a small rise and approached a stream called the Rooipoeier Spruit.

It was just about midnight. The troops were dismounted and told to maintain their extended formation until daylight. A big Western Australian, with a tremendous yawn, voted: 'Fighting a damn nuisance ... at this hour of night!' (This comes from the account of Bert Roy, war correspondent with the Western Australians, quoted in Chamberlain and Drooglever, 2003, p280). Once it was light, a detour was decided upon. The column moved off the road to their right. There was greater apprehension that the Boers would evade a clash than any serious concern that they were in any danger. They crossed the Rooipoeier Spruit a little downstream, past its confluence with the Koster River, turning once again, this time to their left, to cross the Koster River. Just before they crossed what was little more than a trickle at that time of year, they picked up another road leading back to the main road from Rustenburg. The occupants of a large Boer farmhouse at the crossing watched them as they passed by.

Turning towards the west along the main road they then entered a small valley. The road led to another crossing of the Koster River, with rising ground on the other side. To their left was a scrub-covered koppie and, to the right, the ground sloped down to the river. Not far from the river was an abandoned farmhouse. The advance guard spotted a considerable number of Boers on their left, but Airey told them to push on towards Elands River. Trooper Gould, with his Raleigh bicycle, pointed out the location of the Boer laager.

Airey was with the advance guard, but he now led the New South Wales squadron to the right, away from the main road. A message to Captain Richard Echlin ordered him and his Queenslanders to keep to the main road. They had passed the koppie on their left when the Boers, hidden in the scrub, opened fire on them. Only one man was hit, and one horse, and the Australians quickly dismounted and formed a line to the left of the road.

There was no cover at all except for the long grass. The Bushmen could only lie flat and the first man hit was a Queenslander, Bugler Herbert Keogh. When they heard firing on their right flank and left rear, they 'showed uneasiness', but Echlin and his officers thought they could hold out until darkness would give them a chance to escape. Some, unable to move, fell asleep and one even made the wry comment: 'I wonder if the bastards will stop for dinner?' (quoted in Wilcox, 2002, p110). Trooper Gould jumped into a donga, but then decided to ride on and managed to get half a mile along the road to Elands River. Then he ran into some Boers, threw his bicycle into the bush, and crawled back to his fellows in the river bed.

The horses

The horses were led away to the north, five to a man, but the animals were a prime target for the Boers' sharpshooting. They were taken down to the river, where there seemed to be at least some cover. Most of them were killed during the morning as some Boers appeared on the north side of the river. Numbers of horses stampeded and ended up with the Boers. Some of the horse holders attempted to pacify the unmanageable horses and several managed to mount and ride away, some ending at Elands River and others taken prisoner by the Boers. According to Lieutenant Charles Brand, 3rd Queenslanders: ' ... in ten minutes only fifteen horses were alive out of the 250 ... ' (Harvey, 1994, p64). Trooper William Cowley, 3rd Western Australian Bushmen, described the scene: 'The whole place was covered with dead and dying horses ... ' (letter written from Magato's Nek, 29 July 1900, quoted in Coetzee, 2003, p 4).

The Boers were invisible and their Mausers had smokeless ammunition. The Australians at first tried to fire a few volleys but these had no effect. With nothing to fire at, for some hours they lay flat in the grass, any movement provoking a shower of bullets. Captain Echlin found a small ditch and managed to get some of the wounded to shelter. Colonel Airey took shelter in the abandoned farmhouse which was a makeshift hospital, and numbers of Queenslanders and New Sduth Wales men also used the ruined mud walls as cover. Some of the Boers advanced to a hedge on the eastern side, so that fire was coming from three sides. With ammunition running short, a young bugler, Artnur Forbes, ran out from the farmhouse and ransacked the saddle wallets on a number of dead horses (Harvey, 1994, p67. Forbes was awarded the DCM. The citizens of Brisbane presented him with a silver bugle and a purse of sovereigns).

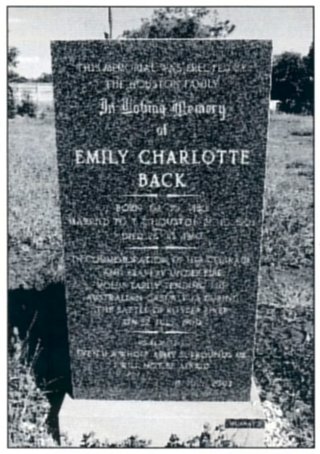

Emily Back

The monument to Emily Back in the grounds

of the Koster River School.

(Photo: By courtesy, Peter Scholtz).

At some time during the morning, a young girl by the name of Emily Back arrived at the farmhouse looking for medical assistance. She had attended to the wounds of a Victorian, who had been injured when the horses stampeded. The soldier had made it to the farm, Woodstock, where Emily was a teacher at a school. Seeing the other wounded around the farmhouse and further afield, she rendered assistance to a number of these, all the time under heavy fire. (Smuts, 1994, p96, writes that the 'Boers would not fire on a woman'). There is mention, too, of a Miss McDonald, but it seems that she remained at Woodstock with the wounded man.

Reinforcements

The Boers had first attacked at about 08.00 and, as the time went by, there were shouts for Airey to give orders. No orders came and Major Harry Vialls of the Western Australians at the end of the line closest to the Boer position on the koppie, decided to take the initiative. It was about 14.00. 'Get together what men you can and we'll charge the hill!' he told his officers. The charge was made by a series of short rushes and the Boer trenches were overrun.

At about the same time, reinforcements from Rustenburg came into sight, under the command of Captain Charles FitzClarence, whose Protectorate Regiment fired a number of volleys at the Boers, who were then retreating to the south. Smuts (1994, p95), no admirer of Baden-Powell, wrote that the latter, in response to urgent calls for reinforcements, sent 'small driblets which each in turn suffered the fate of the force they were sent to relieve'. This is doubtful; there is no record of such small actions.

Colonel Airey sent several notes by orderly to Major Vialls, apparently suggesting a surrender as he and Holdsworth felt that, with all their horses killed and ammunition running short, their force would be unable to hold out until dark. They had no white flag and so they improvised one with five white handkerchiefs knotted together. It was fortunate that the Boers did not catch sight of this symbol of surrender and take advantage of it. Vialls received three messages from Airey, telling him that they were to surrender, the third message being 'a peremptory intimation that orders must be obeyed', whereupon Vialls marched down the slope and confronted Airey to inform him that his men had captured the main Boer position (reported by Bert Toy, quoted in Chamberlain and Drooglever, 2003, pp 289 to 290).

Lieutenant-Colonel Lushington, who led the relief force, arrived half an hour before sundown. He was loath to remain any longer than necessary. Wounded horses were despatched by revolvers under the fire of a few determined Boer snipers. Lushington did not pursue Lemmer's Boers, who were fleeing southwards. As darkness approached, he was required to shepherd the survivors back to Rustenburg. Thus, orders were given to undertake the march back to Magato's Nek and Rustenburg, with only about thirty mounted. Not all the horses had been killed; the Boers claimed to have captured as many as a hundred, but that still left 170 dead horses on the field. It must have been a trying march, eight miles (12.8 km) to Magato Nek and another four (6.4 km) into Rustenburg. Echlin said that 'the last four miles told, the poor chaps were rolling and staggering like drunken men. They did not trouble about supper and slept the sleep of the just until daylight' (official account quoted in Chamberlain and Drooglever, 2003, p 293. According to Smuts, 1994, p 96, the Australians arrived 'hatless, breathless and with bleeding feet).

The body of Captain Claude Robertson of the New South Wales Citizen Bushmen was taken to Rustenburg and buried in the old cemetery. True to tradition, the rankers were buried near the ruined farmhouse, to be reinterred in Rustenburg in 1905. The human casualties were comparatively light in relation to the losses among the horses. The Boers' objective was clearly to eliminate their enemies' mobility for then they were surely trapped. However, Smuts (1994, p95) explains that Lemmer did not have enough men to risk an assault on the Bushmen lying prone and virtually invisible in the long grass. A young Boer, Lodewyk Botha, who had been wounded and ended up being captured, told his captors that 'there were about 1,000 Boers' and that they had the Bushmen surrounded. A letter from Private A M Davies (quoted in Chamberlain and Drooglever, 2003, p292) suggests that the Boers thought that there was a trap being prepared for them because the Bushmen were keeping so still. It is unlikely that Lemmer's force amounted to much more than 100.

BRITISH CASUALTIES

| Killed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Captain Claude William Robertson | NSWCB | KIA | 22.07.00 | |

| Lieutenant John Leask | 3QMI | DOW | 28.08.00 | |

| 404 | Sergeant David Hamilton Pruden | 3VB | KIA | 22.07.00 |

| 395 | Sergeant Herbert John Goodman | 3VB | KIA | 22.07.00 |

| 320 | Trooper Robert Cameron | NSWCB | KIA | 22.07.00 |

| 418 | Trooper Samuel Joseph Oliver | 3VB | KIA | 22.07.00 |

| 488 | Trooper Henry Oliver Walford | 3VB | KIA | 22.07.00 |

| 518 | Trooper Norman Campbell | NSWCB | DOW | |

| 432 | Lance-Corporal James McLure | 3VB | DOW | 26.07.00 |

| 440 | Trooper John Irwin McCartney | 3VB | DOW | 31.07.00 |

| Severely Wounded | ||

|---|---|---|

| Surgeon-Captain Frederick John Ingoldsby | 3WAB | |

| 287 | Corporal James Blair | 3QMI |

| 540 | Lance-Corporal John James William Errol Peters | 3VB |

| 191 | Trooper George Matthew Jorgenson | 3QMI |

| 476 | Trooper William Harris | 3VB |

| 6 | Trooper William Oliver Jones | 3WAB |

| 20 | Trooper Jeremiah Scott | 3WAB |

| Slightly Wounded | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lieutenant John Davies | 3WAB | |

| Lieutenant Arthur Eckford | NSWCB | |

| Lieutenant Richard Henry Walsh | 3QMI | |

| 76 | Private George Augustus | 3WAB |

| 141 | Lieutenant Felix Bernard Theodore Koch | 3QMI |

| 284 | Trooper George Richard Forrest | 3QMI |

| 193 | Bugler Herbert William Keogh | 3QMI |

| 182 | Trooper Thomas Walters | 3QMI |

| 174 | Trooper James Delore | NSWCB |

| 431 | Trooper John Kennedy | 3VB |

| 455 | Trooper William Woods Anderson | 3VB |

| 381 | Trooper Lilford Thomas Butler | 3VB |

| 383 | Trooper Sydney Benjamin Brooker | 3VB |

| 400 | Trooper J. McCastle | 3VB |

| 500 | Private William Henry Bastian | 3VB |

| 15 | Private Edmund Cox | 3WAB |

| 52 | Private Joseph Leeson | 3WAB |

| Taken Prisoner | ||

|---|---|---|

| 439 | Trooper A. Hayes | NSWCB |

| 255 | Trooper A. Wise | NSWCB |

| 223 | Trooper G. Woodley | NSWCB |

| 64 | Trooper J.W. Hewitt | NSWCB |

| 528 | Trooper C. Gardiner | NSWCB |

| 384 | Trooper S. Rowley | NSWCB |

| 17 | Trumpeter A.H. McKoy | NSWCB |

| Missing | ||

|---|---|---|

| 561 | Trumpeter Harry Haycroft | 3VB |

| 85Trooper Charles Allen Lyons | NSWCB | |

| BOER CASUALTIES |

|---|

| Killed |

| P.W. Venter* |

| C. Malan* |

| J. (Fanie) Viljoen* |

| Spencer R. Drake* |

| D.S. du Toit |

| S.F. Malan. |

| (* Names on the monument at Koster River) |

| Wounded - 4 men |

| Taken prisoner |

| Lodewyk Botha, the son of Commandant J.D.L. Botha. |

The battlefield today

The battlefield today is easily identified at the Moedwil School along the N4, west of Magato's Nek. A monument to Emily Back has been erected within the school grounds to recognize what Jan Smuts (1994, p96) called 'one of the bravest deeds of the war'. Baden-Powell recognized her contribution and wrote to the Chief of Staff in Pretoria, asking him to 'bring to the notice of the Field-Marshal Commander-in-Chief the gallant conduct of Miss Back during the engagement at Koster River on 22 July 1900'. This letter never reached its destination as it was intercepted by the Boers. However, Smuts (1994, p96) said of this letter that '[t]his recommendation I felt happy in saving from the wreck of [Baden-Powell's] intercepted correspondence and in subsequently presenting to the girl...' The original letter is now a part of the collection of Mr A C Houston, her grandson. On the crest of the koppie once occupied by part of the Boer force is another small monument which has, sadly, been vandalized. It is a short climb to get to the top, but there is, today, a great deal more bush in the area and the landmarks are no longer visible or easily identified.

Two weeks after the battle at Koster River, the camp at Elands River was attacked, surrounded and besieged by De la Rey and a much larger commando than Lemmer had had at Koster River. The heroic defence here by 505 Australians and Rhodesian colonials, who held out for twelve days in horrendous conditions, has rightly overshadowed the clash at Koster River.

Bibliography

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org