The South African

The South African

Introduction

Pat Rundgren's fascination for gallantry medals to Second World War aircrew began way back in 1973, when Arthur Rose, the District Accountant, showed him scars of where he had almost been chopped in half by an enemy fighter in the turret of his Wellington bomber during the war. This sparked an interest in Second World War aircrew that has remained with him ever since. It takes a special kind of courage to sit, freezing, in a flying tin box, droning towards a distant target, knowing all the while that, mathematically, you don't have much of a chance of making it back home. Even those dismal odds shorten as the number of sorties mount. So, as aircrew, you subconsciously know that, before the day is out, you're likely to be dead, having suffered a prolonged and painful plunge, in your stricken, flaming aircraft, hurtling thousands of feet towards the ground. One of the advantages of collecting South African Second World War awards is that, unlike their British counterparts, the recipients' names are always engraved on the campaign medals, which makes researching the individual concerned much easier. This article illustrates two medal groups to former members of 24 Squadron, South African Air Force. Part of 3 Wing, South African Air Force, 24 Squadron was a bomber squadron during the Western Desert (1941-1943) and Italian (1943-1945) campaigns. The squadron flew Martin Marylands, Boston llls and later B 26 Marauders. The Squadron lost 182 members, either killed in action or who died on active service between 1941 and 1945. This article concentrates on the role of two members of the squadron, whose logbooks provide a riveting account of their wartime experiences.

Lieutenant Laurie Doveton AFC

One man who was lucky enough to have survived being shot down was Lieutenant 'Laurie' Doveton AFC. His first operation took place on 25 October 1943, when he

participated in an attack on a bridge on the Sangro River in Italy. On 18 February 1944, Laurie experienced his first attack by German fighters, which he recorded thus

in this logbook:

'Raid on enemy vessel in Rhodes Harbour. Bombed from 10 000 feet. Three direct hits on quay. The "Earth" of flak. Got 35 holes. Elevator trim shot away.

Mid-upper turret gunner hit in the arm by shrapnel. Formation attacked by three Me 109s. One 109F was seen to go up in smoke and disappear through cumulus cloud.

Quite a session!'

Boston aircraft, 24 Squadron (Photo: By courtesy, P Rundgren).

A week later, his log book entry for 25 February reads: 'Raid on shipping in Portolago Bay. Bombing spoilt on account of heavy, accurate flak, and attack by five Me 109s. Capt Ribbink hit in port engine nacelle, which burst into flames. Two 109s shot down. One "probable". Two FW 190s also attacked but driven off by gunners. Two Ju 88s stooged about above us but did not attack - just as well! Another sesh!'

The raid on Portalago Bay was reported in the Squadron Diary thus: 'Just before reaching the target area at 13:57 hours, the formation, flying in a box of 4 [aircraft], at 10 500 feet, was attacked by 7x Me 109s and 2 x FW 190s. All attacking [aircraft] carried out individual assaults from all quarters and no attempt at an organised attack was made. Attacks were persistent and continued for at least 15 minutes during the bombing run, while bombing, and after leaving the target area, following the formation as far as Stampalia Island. One FW 190 came into attack from starboard after bombing and [Aircraft] "S", Capt A F Shuttleworth, broke formation and made a direct attack with all guns firing that were possible to bring to bear. This [aircraft] was seen to dive sharply and crash south of Kos Island. '

'One Me 109 came into astern attack firing from 7/800 yards, closing in to 150 yards. All gunners were able to bring fire to bear and this ale was seen to disintegrate in the air. '

'One FW 190 attacked [Aircraft] "F", Capt F Ribbink, coming in from approximately 9 700 feet to port and climbing to a belly assault. At 150 yards this ale had performed a half roll and opened fire with cannon fire, almost immediately slipping down out of combat. Alc received hits in the starboard engine at approximately 14:01 hours, and flames enveloped the engine and main plane. This ale carried on in tight formation for at least five minutes and thus enabled the crew to bail out safely, and the ale was then ditched at 14:07 hours. '

'The waist gunner of [Aircraft] "M", Flight Sgt Glass, opened fire from a range of 100 yards after changing the position from which he had observed the attack on [Aircraft] "F", and believed that it was the same FW 190 that had carried out the attack which received hits in the belly from his guns. The fighter went into a spin after emitting a large puff of smoke, pieces seen to fly off the ale, and the hatch apparently breaking away.

'Heavy, intense [anti-aircraft fire] from target area. [Two aircraft] badly holed by [machine-gun] and cannon fire'.

Laurie Doveton was shot down on his fifteenth sortie on 6 March 1944, in an episode that came to be known as the 'Marauder Massacre', when 24 Squadron lost four aircraft out of six.

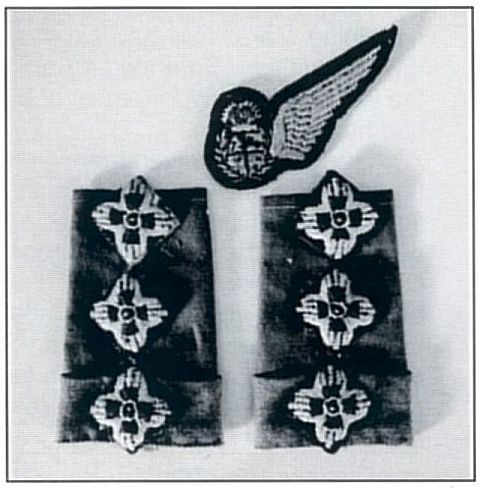

Lt Doveton's pilot's wings and epaulettes (Photo: P Rundgren).

This event is described in Per Noctem, Per Diem, pp 125-6: 'On 6 March (1944) an attack was made on shipping in Scala Bay (Santorin Island) with Captain Shuttleworth leading the formation; Lieut Bell, flying No 2; Captain Braithwaite, No 3; Captain Frolich, No 4, leading the sub-flight; Lieut Doveton, No 5; and Lieut Bowles, No 6.'

'At 13:00 hours the formation was in a position 36.20 N 24.00 E when enemy fighters began an attack that lasted for 90 minutes. There were nine Me 109s and three FW 190s. These originally appeared to be operating in groups of four, each group singling out a single bomber and pressing home determined attacks. The fighters, although fitted with long-range tanks, appeared to be operating a "shuttle service", coming in to attack from every conceivable angle, and peeling off to land and refuel as soon as others came to take their places.'

'The fighters jettisoned their tanks and came into the attack from either side of the formation at about five and seven o'clock, doing their familiar half-roll onto their backs when about 200 yards from the bombers and then breaking away underneath and downwards, when they would present their undersides to the' waist gunners. As usual we had trouble with our tail guns and only about half of them were operating.'

'At the time of the first attack the second sub-flight had lagged behind somewhat so that the tail guns of the first sub-flight were unable to give them any support. Several fighters attacked Marauder "E", flown by Lieut L L Doveton, which was badly damaged and dropped out of the formation. The pilot and the co-pilot, Lieut. Steenkamp managed to crash-land at Oran on the Turkish coast.'

'A few minutes later four fighters attacked Marauder "V" piloted by Lieut G A Bowles and the aircraft was seen to go down and hit the sea, where it burst into flames. He, with his crew, were all killed.'

'The fighters then concentrated on Captain Frolich's aircraft, Marauder "L", and he pulled up under the formation with smoke streaming from his aircraft. The undercarriage then came out and the aircraft lurched downwards in a spin. Four parachutes were seen to open from the aircraft but all the members of the crew were killed. In a matter of minutes the second flight had been wiped out, partly due to some of the tail guns not working, partly due to the fact that they were too far back to get supporting fire from the first sub-flight and also due to the unforeseen strength of the fighters and their tactics of dividing the available firepower by synchronising their attacks from different quarters.'

'The remaining sub-flight fought on until the target was reached, where the fighters gave them a temporary respite until they had gone through the flakdefended area on their bombing run. The ships were there all right and flak was medium but inaccurate, so a long run-up on the target was possible, but the bombs overshot by about 400 yards.'

'As soon as the Marauders had turned off the target the remaining fighters renewed their attacks and the fourth Marauder, "W", was lost when at 14:29 hours in position 35.50 N 22.28 E it was hit in the starboard engine, which immediately caught fire. The fire reached the cockpit and as it gained in intensity the starboard wing broke off and the aircraft plummeted into the sea. Before the aircraft hit the sea, however, the tail gunner, Lieut C W Heaven, was seen engaging the fighters, one of which was destroyed and seen diving towards the sea, smoking fiercely. The crew of"W" were all killed.

The tail gunner of the leading aircraft wept as he saw George Bell go down as he sat behind his jammed and useless guns. The remaining two Marauders had three serviceable guns between them and still the fighters persisted in their attacks. The fight only ended in a position about 30 miles west of Crete after the two remaining Marauders had expended 3 000 rounds of .50 ammunition. So ended an epic 90-minute battle the longest that any formation of bombers in the SAAF had had to undergo.'

In an interview given many years later, Laurie said that his aircraft was badly damaged during the first fighter attack. During the second attack, a cannon shell burst under the cockpit floorboards in the control column box. Several bullets hit his armoured seat from behind. With no elevator or aileron control, Laurie ordered his crew to bale out and Ruthkin, Collins and Fourie jumped out at 10 000 feet (3 408m). Their parachutes were seen to open, but they landed in the sea and drowned. Their bodies were never recovered.

Phillips, the navigator, had attempted to open the bomb doors to jettison the bomb-load and the longrange fuel tanks. The bail-out procedure was for the pilot, co-pilot and navigator to jump through the bombbay after the doors had been opened. In this instance, the bomb doors malfunctioned and would not open as the piping and hydraulics were damaged. With the aircraft out of control and losing height, Laurie climbed back into the cockpit and initiated the emergency procedure to open the bomb doors, whereupon Phillips bailed out. His parachute was also seen to open, but he also subsequently drowned.

Before Laurie and Steenkamp could follow, the bomb doors closed again. As they both scrambled back up to the flight deck, Laurie noticed that a 250lb bomb and a 500 gallon tank of fuel had 'hung up'. With the aircraft spinning downwards, Laurie then attempted to open the trap door next to the front wheel well, but found it to be impossible as the hydraulics had been shot away.

The only remaining option was to attempt to regain control of the aircraft, which he managed to do just before it hit the sea. Rather than ditch, he flew on trim-tabs and rudder towards the island of Kos, but at the last moment decided to make for Turkey as Kos was still occupied by the Germans.

As the aircraft approached Turkey, the fuselage lights all blinked on, indicating that the aircraft was running out of fuel. Without enough height to clear the coastal cliffs, Laurie turned to starboard and flew parallel to them, turning into the first cove at a height of 400 feet (122m). With both engines spluttering, they crash-landed on some agricultural land bordering the beach.

The aircraft caught fire immediately, but the force of impact jammed the roof doors solid. Both Laurie and Steenkamp managed to escape through the pilot's side observation window, which was only designed to permit head clearance to observe the engines on start-up!

As Laurie described it, 'we ran like hell and dived behind a mound of earth as the aircraft went up'. He survived with only singed hair!

After the crash, some locals found Laurie and Steenkamp, mistaking them for Russians because of the red tabs on their epaulettes. They were taken on horseback on a 3-day journey to Aiederon, the first large town. 'We were filthy, unshaven and saddle-sore. At the house we were told we were to see the General. We got stroppy and said we would not see him in our present state. He was informed of this and ... magic! Our battledress was whipped off ... shave, haircut and a lovely hot bath. Our uniforms had been pressed and now we were ready to be interviewed. '

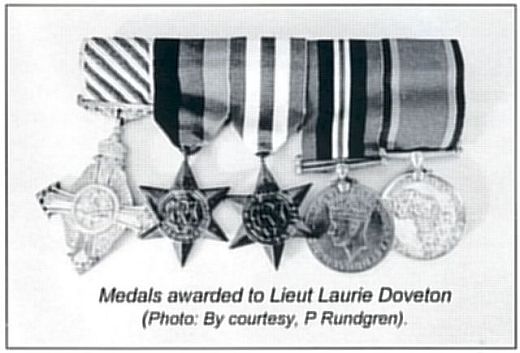

Medals awarded to Lieut Laurie Doveton

(Photo: By courtesy, P Rundgren).

In 1946 Laurie successfully applied for a job as flying instructor with the Royal Air Force (RAF). He was sent on a two-year tour in the RAF Component to the British Services Mission to Burma, based in Rangoon. Upon his return to the United Kingdom in April 1952, Laurie was involved in accident investigations and training, variously based at Cranfield, Cosford, Aden and Khormaskar. The London Gazette of 1 July 1952 records his promotion to Squadron Leader.

His Air Force Cross (second type), awarded for his services in Burma was Gazetted on 1 January 1953. Only 411 Air Force Crosses of this type were issued.

He went on early retirement in August 1958 and returned to Durban, South Africa. By then, he had flown some 2 423 hours in 33 different types of aircraft and had landed at 151 different airfields.

Captain Peter Atkins, DFC

The author's second medal group from 24 Squadron belongs to the remarkably self-effacing Captain Peter Atkins DFC, who served as a Leading Observer on two tours of operations. Operational tours in the RAF were calculated on 30 raids and then a spell for 'rest and recuperation' - usually at a training unit. The South African Air Force was rather different. During Atkin's first tour in the Squadron (8 June 1942 to 30 March 1943) he completed 90 operational sorties, including six sorties in his first two days there (two on 11 June and four on 12 June 1942) with Lieutenant David Liddell (later Major, DSO, DFC) as his pilot.

He clocked up another 33 sorties during his second tour (19 February to 20 August 1945), which was terminated by the end of the War, giving him a total of 123 raids - a remarkable achievement by any standards.

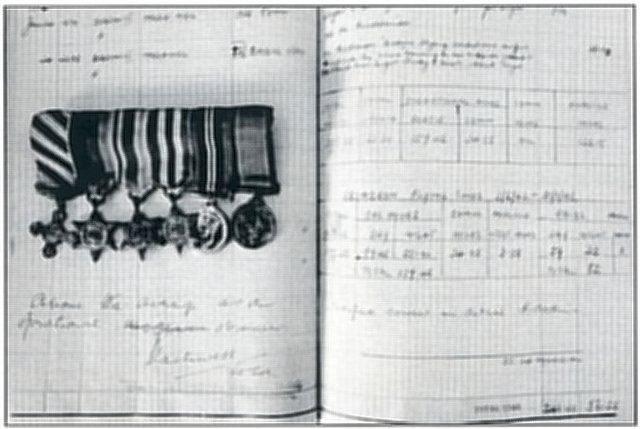

Captain Atkin's wartime logbook and miniature medals

(Photo: By courtesy, P Rundgren).

Colonel Cecil Margo DSO, DFC, the Commanding Officer, 24 Squadron at the end of the War, wrote the following foreword for Buffoon in Flight:

'Peter Atkins rose to be one of the most successful and highly respected observers in the South African Air Force in the Second World War. The award of the

Distinguished Flying Cross gives some indication of his prowess. '

'As the leading observer of his squadron he achieved remarkable results. His balanced judgement, calm temperament, dedication and tenacity inspired enormous confidence. It is worth recording that, in a particular series of attacks on enemy installations and armour, his repeated successes won for him the affectionate sobriquet of "The Arson King".'

'Later, Atkins qualified as a Category "A" Bombing Leader - one of only twd in the SAAF. Towards the end of the War, Atkins returned to 24 Squadron where he became the last leading observer the Squadron had on operations.'

'His Commanding Officer, Colonel Blackwell assessed him as "[w]ell above the average as an operational observer".'

Pilot's wings and pips of Captain Peter Atkins

(Photo: By courtesy, P Rundgren).

Peter Atkins earned his nickname' The Arson King' because of his predilection for causing huge fires with his bombing, albeit sometimes unintentionally. During an attack on Mersa Matruh, he forgot to order the 'pilot to open the bomb doors prior to dropping their load, which meant that by the time the doors were eventually opened, the bombs dropped way off target:

'We were barely out of range when the startled voice of Reg Jones exclaimed: "Christ, look at that!". Two or three miles to the east of Mersa Matruh there was a magnificent fireworks display with ammunition exploding in all directions. It transpired that our errant bombs had landed slap on a twelve-gun flak battery. Certainly I could claim no credit for the destruction but I have often wondered what the survivors, if any, must have thought after being hit by bombs released by a plane so far overhead. Maybe they thought it was the work of some new super bomb-sight?'

A snippet from his autobiography highlights the intensity under which the Squadron had to perform, in this particular instance on 1 September 1942, while executing bombing raids in the Deir el Regil area south of Alamein: 'On our first raid there was a mid-air collision but both aircraft got away with it. Lieutenant de Marillac was flying Number 2 on his leader, Dirkie Nel, when a burst of flak forced his plane onto that of the leader. De Marillac's port propeller chewed a huge chunk out of Dirkie's starboard wing, while his port wing impaled Dirkie's machine just aft of the gunner's cockpit. When the two aircraft disengaged from this impromptu encounter, a large part of De Marillac's port wing was missing while the tail plane of Dirkie's aircraft was flapping. Amazingly, both got back safely.

'On our second raid John Pocock had the tail of his Boston shot away and only his observer, Bob Shuter, managed to bale out. Seconds later a Mitchell was shot out of the sky and again there was only one survivor. '

'On our third and last raid of the day almost every aircraft was heavily holed. Our own aircraft looked a bit like a colander. Our fighters had one of the most shocking days of the desert war. The Luftwaffe was out in force and its ace pilot, Marseille, claimed seventeen victims during the day.'

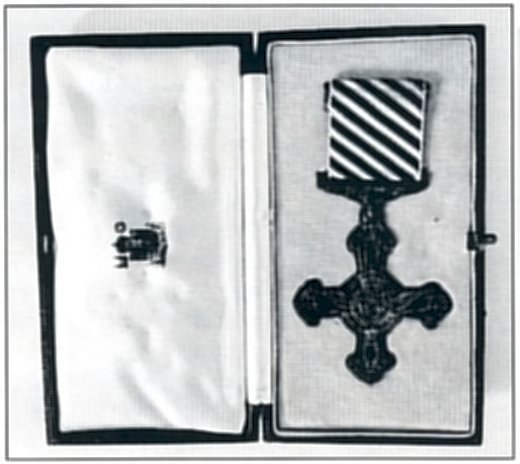

Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) awarded to Capt Peter Atkins, 24 Squadron

(Photo: By courtesy, P Rundgren).

There were, however, also lighter moments -

' ... an entertainment unit parked itself on us for a couple of days. Needless to say it was our senior officers who picked the plums out of that particular operation. The night after the unit left us, one of our senior officers, who shall remain nameless, looked ruefully into his wallet and remarked: "That little lot certainly f****d my paybook". To which his observer replied, "Surely, Sir, a matter of tit for tat!'

Post-war, after a couple of false starts, Atkins became the racing editor of the Cape Argus and continued in racing journalism, and finally as racing editor of The Star up to his retirement.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org