The South African

The South African

'Marrieres Wood is forgotten, in part, because there is no satisfactory British name for the larger battle of which it was part' (R Gray, 1991, p 6).

The strategic situation in early 1918

Due to the Russian collapse, forty German divisions could be moved from the Eastern to the Western front in the spring of 1918. This gave the Germans, according to their perceptions, a brief window of opportunity, but they had to strike before more American troops arrived in France. In addition, the British naval blockade, combined with poor harvests, was causing starvation on the home front and there was increasing labour unrest in Germany. Morale in the army was low and, on the High Seas, the unrestricted U-Boat campaign had failed to achieve its objective because of the introduction of convoys for Allied merchant ships.

The Germans thought they had found the solution to the deadlock on the Western Front - storm troop tactics, as had been tried with success at Cambrai in 1917. This involved substituting long, drawn-out bombardment with short, intense action, designed to paralyse, rather than destroy, the defenders. At the same time, identified enemy batteries would be deluged with gas shells to disrupt defensive fire.

As the bombardment got underway, small groups of soldiers would advance and attempt to infiltrate the enemy positions. Serious opposition would be bypassed, to be dealt with later and to prevent enemy relief forces from reaching the position. The key was to disrupt and then destroy the enemy's defence.

From the options available, the German military commander, General Erich Ludendorff, chose Operation Michael after a lengthy tour of the front, possibly because this plan was less dependent on the weather (Gray, 1991, pp 29,31).

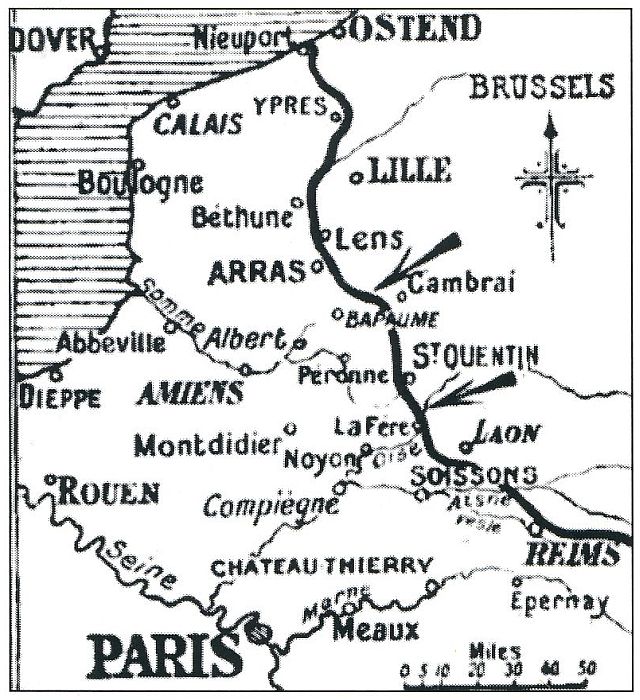

The German Spring Offensive, 21 March 1918

(Source: Times History and Encyclopaedia of the War,

Vol 18, Part 224, p74).

The Allied position

British Fifth Army strength was slender and, in addition, the British had taken over 42 miles (68 kilometres) of front from the French Third and Sixth Armies. Furthermore, not all forward zone positions were prepared (Gray, 1991, pp 24, 33).

The 9th Scottish Division was on the extreme left of the Fifth Army. On its right was the 21 st Division and, on its left, the 47th Division. The 9th Scottish Division was deployed with the South African Brigade on the right and the 26th Brigade on the left. The South Africans were deployed in a sector which ran from just north of the Quentin Redoubt for some 2 000 yards [1 828 metres] to just south of Gauche Wood. The position could not be held along its length. Instead, the front included a series of posts and redoubts which covered the ground with their fire (Buchan, 1991 reprint, pp 159-162) .

This represented a new system of defence, which created a forward zone of concealed machine gun nests. This was designed to break up the German attack. Behind the forward zone was the battle zone, the main line of resistance. This consisted of deep, well-wired redoubts and this was where the divisional artillery was positioned. Last was the rear zone, which was a battle zone between four to eight miles [6.4 to 12.9 km] behind the main battle zone (Gray, 1991, P 33).

First SA Brigade had placed the 1 st and 2nd South African Infantry (SAI) regiments in the forward zone. A company of 1 st SAI garrisoned the important Quentin Redoubt and, 2nd SAI, the equally important Gauche Wood redoubt. The 4th SAI was in the battle zone. The South African brigade had only one bayonet to a yard; the Germans mustered four to the yard (Buchan, 1991 reprint, pp 159-62; Digby, 1993, P 269).

The attack on Gauche Wood

There was a lull before the storm. According to John Buchan (1991 reprint, p 163), the eight days before 21 March 1918 were the quietest the South Africans had ever known.

The weather conditions favoured the Germans. On the evening of 20 March 1918, a thick ground mist formed, which became a thick fog (Edmonds, 1935, p 161). The German bombardment began at 04h40 the following morning. Gray identified seven phases of the bombardment. The first phase, which he calls 'General Surprise Fire', lasted for two hours, the first twenty minutes of which sawall positions deluged with high explosive (HE) and gas in a proportion of four HE shells to one gas. At 05hOO the trench mortars ceased fire. Then the lighter guns, smaller than 17cm, fired HE on the infantry positions in the forward zone. The positions in the Battle Zone were bombarded with HE shells and gas shells. Phases Two to Four ran from 06h40 to 07h10 and are not described in detail by Gray. The fifth phase was marked by most guns firing on the infantry defences.

The intermediate defences were bombarded with HE shells and gas shells. Phase Six was a repeat of Phase Five with smoke shells added to thicken the fog. Phase Seven had howitzers shelling the trenches with HE shells and mortars, and field guns bombarded the forward zone beyond the trenches.

The storm troops began cutting the wire at 09h00 and, by 11h10, only fifteen of the British redoubts continued to hold out (Gray, 1991, P 35).

Two of these were the South African-held redoubts of Quentin and Gauche Wood: For the South Africans, the main impact of the attack fell on Gauche Wood. A machine gun nest was overrun but the redoubts held. The German attack was fiercely resisted, and the Germans were forced to dig in. As the fog lifted, the defence of Gauche Wood was strengthened with artillery support and flanking fire from the Quentin redoubt. However, the South African position was becoming precarious, because of events to the south. The South African right flank was exposed (Buchan, 1991 reprint, pp 167-8). It became necessary to recapture the Chapel Hill position. This was done in the afternoon by a company of the 4th SAI Regiment (Buchan, 1991 reprint, p 168-9).

Retreat to Marrieres Wood

In spite of Chapel Hill having been" recaptured, orders were given to retreat. There was no serious attack on the South Africans on 22 March 1918, but on that day the overall British position worsened. A further withdrawal was ordered, amid bad communications. For Captain Garnet Green and his men of 'B' Company, 2nd SAI, there was no chance to retreat and they fought to the last (Buchan, 1991 reprint, p 174).

The retreat was successfully carried out. The South Africans, by then reduced to two regiments, were holding a ridge to the west of Marrieres Wood (Buchan, 1991 reprint, p 180).

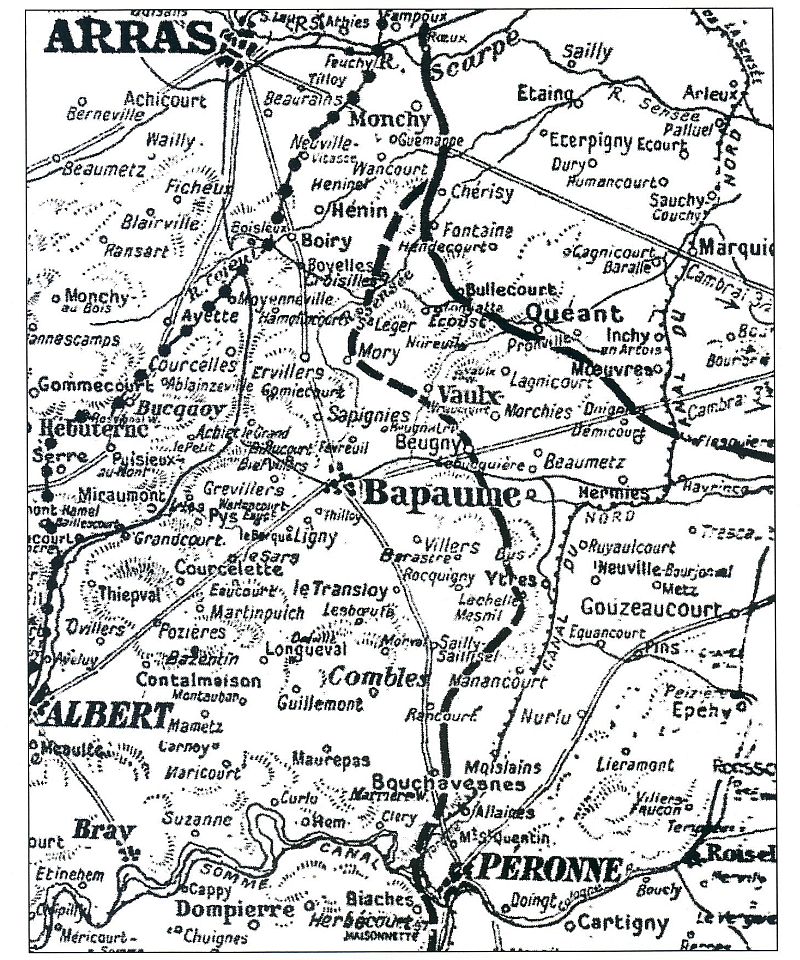

Detail of a map of the battle zone, showing the strategic location

of Bouchavesnes and Marrières Wood on the Peronne-Bapaume road.

(Source: Times History and Encyclopaedia of the War, Vo/18, Part 223, p44).

The battle

The cost of the retreat had been high, especially in officer casualties (Digby, 1993, p287-92). The South African brigade, then only 500-strong, had taken up a position on a ridge behind the northern point of Marrieres Wood. The position gave effective observation eastwards and a good field of fire, but it was a trap because of the open terrain to the west. The defences were made up of a line of disused trenches. One trench was good, but the others were bad. Furthermore, there were many shell craters. Manning the position were the 1 st and 2nd South African Infantry Regiments, with remnants of the 4th SAI Regiment and a section of the 9th Machine Gun Battery. There were 200 rounds of ammunition per man and a good supply of Lewis Gun drums (Buchan, 1991 reprint, pp 180-2; Digby, 1993, P 297).

Brigadier-General F S Dawson, the brigade commander, was given a verbal order by Major-General H H Tudor, commander of the 9th Scottish Division, to hold at all costs (Buchan, 1991 reprint, p 179; Digby, 1993, P 297).

As the fog lifted on the morning of 24 March 1918, the Germans could be seen massing on the opposite side and the outcome of the battle was inevitable. The brigade records were sent to ttie rear and the brigade prepared for its last stand. At 10hOO, disaster unfolded, continuing for more than an hour, forcing the brigade headquarters to move, but luckily causing few casualties. Shortly afterwards, the heavy gun, which had been firing at the village of Bouchavesnes to the east of the South African position, fell silent. It was the last the South Africans heard of the Royal Artillery (Buchan, 1991 reprint, p 183).

The German attack began with machine gun fire, soon joined by shelling. The gunfire intensified, causing the position to be covered in dust and fumes, with the Germans about 700m from the South African position. They kept their distance out of respect for the South African fire, which came mostly from the Lewis guns, the riflemen hav.ing been ordered to hold their fire until the Germans were within 370m. This was to conserve ammunition. One Lewis gunner, J W S Jeffrey, silenced a field gun at 915m and, when the Germans tried to bring up another gun, he shot the horse team and gun detachment. By midday, a series of attacks from the front and north and south had been beaten off. The position was getting more and more precarious because the Germans were working around the flanks. The other British units had retreated out of supporting distance. By 15hOO the remnants of the brigade were surrounded, but stern measures were undertaken to prolong the defence. Ammunition was taken from the casualties, and wounded men, who could still fight, were sent back to the firing line (Buchan, 1991 reprint, pp 182-5; Digby, 1993, pp 297-303).

The end came just after 16h15. The Germans brought three fresh battalions and the South Africans fired their last rounds. When the position was overrun, there were only 100 South Africans left, including wounded men (Buchan, 1991 reprint, p 187).

The achievement

A recent account of the German offensive has described the South African stand as a verbally ordered magnificent last stand. The brigade fought to the last round against the German 199th and 9th Reserve Divisions. They fought for nearly eight hours. The German advance was delayed for seven hours and caused huge traffic jams (Gray, 1991, P 54). The cost was the end of the old 1 st South African Brigade which had been formed in 1915. All that was left were the base details who had not re-joined the brigade and the remnants of two companies that had been attached to other units. There were only enough to form a composite battalion. The brigade was rebuilt with reinforcing drafts of seventeen officers and 947 other ranks in the first week of April 1918 (Digby, 1993, pp 324-5).

The last stand at Marrieres Wood by the 1st South African Brigade bought the Third [British] Army time to establish the line to hold the Germans at bay. The tragedy is that this stand, like that of the 1 st Battle of EI Alamein in the Second World War, has largely been forgotten. To pay tribute to this forgotten stand, Ditsong National Museum of Military History has dedicated the downstairs room of its Capt W F Faulds VC MC Conference Centre to the battle of Marrieres Wood. For the same reason, the South African Military History Society sponsored the plaque in the room, which tells the story of the battle.

Bibliography

Buchan, J, The South African Forces in France (reprinted 1992, Imperial War Museum, London, and Battery Press, Nashville).

Digby, P K A, Pyramids and Poppies (Ashanti, Rivonia, 1993).

Drury, I, German Stormtrooper, 1914-1918 (Osprey Warrior Series 12, Osprey, London, 1995).

Edmonds, J E, Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1918. The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries (MacMillan, London, 1935).

Gray, R, Kaiserschlacht 1918 (Osprey Campaign Series 11, Osprey, London, 1991).

Gudmunsson, B I, Stormtroop Tactics. Innovation in the German Army 1914-1918 (Praeger, I Westport, 1989).

Middlebrook, M, The Kaiser's Battle, 21 March 1918: The First Day of the German Spring Offensive (Penguin, London, 1983).

Moore, W, See How They Ran. The British Retreat of 1918 (Leo Cooper, London, 1976).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org