The South African

The South African

*This is the proper name of the farm in Afrikaans, as spelled throughout this article. The name was anglicised to 'Abraham's Kraal' in du Moulin's book, Two years on Trek (1907).

Photographs by R W Smith

Introduction

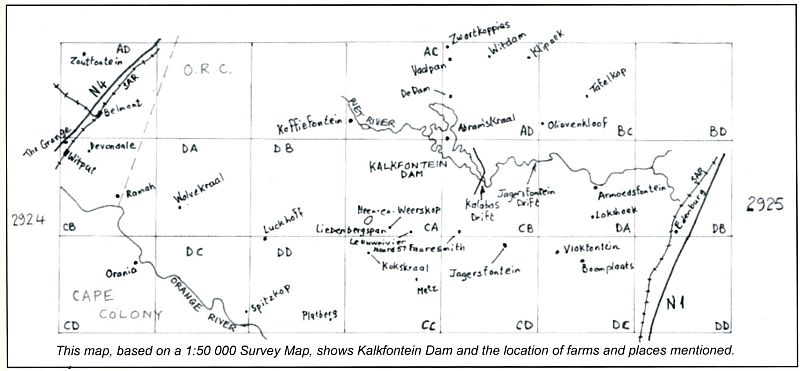

Under the waters of the Kalkfontein Dam in the district of Fauresmith in the southern Free State lie the ruins of the farmhouse of Abram's Kraal. It was here in the early morning of 28 January 1902 that Boer commandos under the command of General Charles Nieuwoudt attacked a British column. The column, which was composed principally of soldiers of the Royal Sussex Regiment under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Louis du Moulin, had chosen this deserted farmhouse and its outhouses, walled garden and kraals for their bivouac that night.

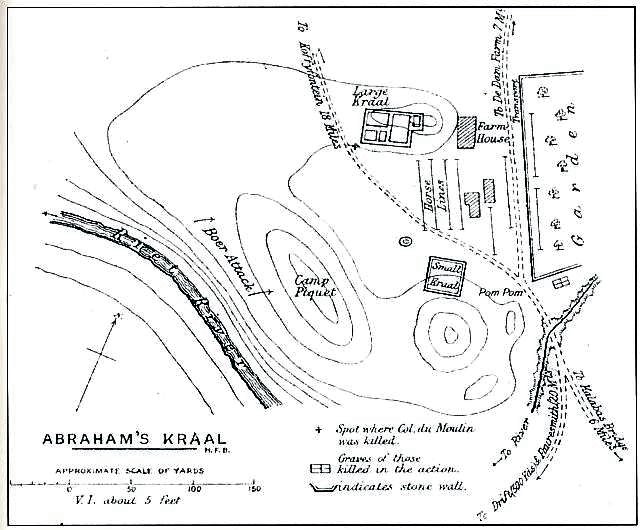

Abram's Kraal farmhouse faced north a short distance from a small rocky ridge along the right bank of the Riet River. The owner had built two kraals to hold his cattle, and perhaps some sheep, as well as a small walled garden where fruit and vegetables were grown. These Boer farm gardens almost invariably contained a small orchard of peach trees. Two barns were used by the soldiers that night while the officers occupied more comfortable quarters in the farmhouse. The close proximity of Biesiesvlei, an extensive shallow pan or pond, where they could water their horses and mules, was an important factor which governed their selection of this place for their night's halt.

The column almost certainly did not take their horses and mules down to the river for water. That number of horses would have been much more easily watered as a large crowd in the vlei, rather than in the river, where they would have had to occupy a long stretch of river frontage, out of sight of the camp around the corner of the ridge. There were 350 mounted men in the column (Du Moulin, 1907, p300; but see also the footnote on p303, which mentions 'about 300, with a Pom-Pom'), as well as a number of carts and wagons drawn by mules. They also had a Pom-Pom (a Nordenfelt 37mm large calibre belt-fed machine gun firing explosive projectiles used by both sides in the war, the name coming from the sound the gun made when fired) on a carriage which had its own team of four mules. It seemed a secure place to spend the night.

The Royal Sussex Regiment was stationed in Aldershot, the British Army's headquarters in Hampshire, when war broke out in South Africa in October 1899. They were on the roster for foreign service but that turned out to be Malta and not South Africa. Eventually the call came for them to embark for South Africa after a period of intensive training. The regiment was with Lord Roberts' advance through the Orange Free State and they were in action at the Zand River before entering the Transvaal. They again saw action at Doornkop, outside Krugersdorp, after which Johannesburg was occupied. They were present at Diamond Hill when Louis Botha sought to halt the advance of the British army along the Delagoa Bay railway line, but then spent much time in garrison duties until February 1901, when they were formed into a mounted column (Du Moulin, 1907, gives a full account of their activities in South Africa).

The British commander

Louis Eugène du Moulin was of French descent, although hailing from New Zealand. He was related to the French settlers who founded the town of Akaroa in South Island. He passed through Sandhurst and joined the 107th Regiment in 1879 which became the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment in 1881. His service experience was in various campaigns in India from 1888 to 1897. Major du Moulin was promoted to the local rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in June 1901, taking command of the column.

From July 1901 onwards there was considerable activity in the southern Free State, where the British army worked hard to find and destroy the commando of General Jan Smuts, on his way to invade the Cape Colony. The British were unable to prevent him crossing the Orange River and moving south and west, eventually getting into the western Cape and close enough to see the lights of Cape Town. The southern Free State had been relatively quiet for most of 1901, but British columns, having been outwitted by Smuts, sought to find General Pieter Kritzinger, some of whose men had acted as a guide to Smuts. Kritzinger's energetic and aggressive Commandant Louis Wessels descended on Lovatt's Scouts at Quaggafontein on 20 September 1901, a farm on the right bank of the Orange River, which included several drifts. Wessels took possession of the enemy's camp in a surprise attack at midnight. Then, unaccountably, he and his commando retreated back the way they had come, not taking advantage of the opportunity to cross the Orange into the Cape and add to the disorder there (Maurice, Vol IV, pp 287-9; Kritzinger, 1904, pp33-6).

On the move

Du Moulin's men might have engaged and captured Louis Wessels and his small band of about 80 men but for a miscommunication with Colonel Herbert Plumer.

Plumer's Australians had a sharp encounter with Wessels at Mokari Drift on the Caledon River on 27 September 1901, but du Moulin's force was too far away to intervene (Smith, 2008). By this time the area of the southern Free State east of the railway line between Bloemfontein and De Aar had become untenable for the Boers. Commandant George Brand reported to the Vereeniging Meeting of Commandants in May 1902, 'that everything had been carried off - there was not a sheep left' (Du Moulin, 1907, p296).

West of the railway line the land was less rugged but more arid. There was general movement of the Boer commandos into this area and the British columns followed. Even the British did not have much in the way of supplies. Captain R C Griffin complained in his diary that he was 'getting tired of nothing but tinned food with an occasional slice of newly killed goat.'

Du Moulin's column was moved into Edenburg on 19 December 1901 and continued south to Jagersfontein Road on the main railway line on the 22nd. Intelligence placed Boer commandos at Jagersfontein, 25 miles (40km) to the west. (According to Du Moulin, 1907, p 296, '[it] was known that the Commandants had been summoned by De Wet to a conference in the north', but no such conference took place). On the evening of 24 December, the column moved out with 350 men of the Sussex Regiment and a Pom-Pom, the wagons following later. They halted for a short while at Boomplaats Hill site of an engagement between Sir Harry Smith and the Orange Free State Boers under Gereral Andries Pretorius on 29 August 1848 - and' then continued on over the broad flat plain stretching across to Jagersfontein. At the farm Vlakfontein, just as the sun was rising, they encountered a Boer commando. The Boers were not prepared for an attack and numbers of them were caught asleep in a donga (a small ravine, sometimes caused by erosion) and rolled up in their blankets. At the cost of two wounded the column had made a very successful raid, as recorded by Du Moulin (1907, p298):

'Heaps of rifles, saddles, bandoliers and other equipment were brought in and piled against the veranda of the farmhouse, the Colonel and the other officers assembled on the veranda, the horses were picketed in lines in front of the house, the men started to brew their coffee over little fires, and a general air of cheerful satisfaction pervaded the place; for it had been a very successful raid. Besides twenty-eight prisoners, the column had taken 52 rifles, 78 bandoliers, 2,500 rounds of ammunition, 105 horses, 96 saddles, 130 blankets, 25 cloaks and 8 bags of wheat.' (A photograph from Second Lieutenant R E Paget's collection portrays this scene and shows the recaptured rifles stacked against the veranda of the Vlakfontein farmhouse).

In British uniform

One of the captives was dressed in a complete British uniform with regimental badges and slouch hat. To deceive their enemy into thinking that an approaching group of riders was friend and not foe was a tactic adopted by the Boers. Wearing captured British uniforms and arranging themselves so as to look like a British formation was quite frequently successful, enabling them to get to close range before, too late, the ruse was discovered. Commander-in-Chief, General Lord Kitchener, had issued orders in September 1901 that any Boers captured wearing British uniforms were to be tried by Court Martial and shot. Griffin commented on the Boer's fate in his diary entry for 24 December: 'One Boer caught in khaki was tried and shot in the afternoon. Very horrid business! He was made to dig his own grave and then shot before a full parade of all the troops and the other prisoners, one of whom was his own brother.' (This incident is also mentioned by Du Moulin, 1907, p298).

Map, traced from the 1924 series,

showing the British route of retirement

Concerned that the Boers might take revenge with an attack on Christmas morning, Du Moulin and his men stood to arms at 03.00 and, soon after sunrise, heard gunfire from the south. This was the action of Colonel A C Hamilton, who scattered a laager near Heen-en-Weers Kop and took sixteen prisoners. He and his men had ,outdistanced their wagons which had an escort of only sixty men. Judge Hertzog and General Charles Nieuwoudt pounced at Kok's Kraal, a short distance away, with their 250 men and overpowered the guards. Three African drivers were shot out of hand and four of Hamilton's men were killed and four wounded. The prisoners, and some of the slightly wounded, were stripped and made to walk to Springfontein, 'an officer among them', according to the Official History (Maurice, Vol 4, p 430).

Du Moulin's column made its way to Fauresmith, which they found to be deserted. They enjoyed the apricots, figs, mulberries and peaches from the gardens behind the houses: 'Paradise', they said. They moved into Jagersfontein on 26 December and found the diamond mines, the richest in the world, to be deserted. Next day they headed back to Vlakfontein. Griffin's diary entry for 27 December told that '[on] arrival there we found the notice to the effect that we had shot a Boer for wearing British uniform, which we had posted on the door of the farm, had been removed - looks as if Boers had been here again.'

Vlakfontein was made the headquarters for the columns operating in the district (Du Moulin, 1907, p300), which were those of Lieutenant-Colonel W G B Western and Major D P Driscoll (Driscoll's Scouts). Colonel A N Rochfort, in overall command of the district, came to Vlakfontein to organise a combined move of the three columns against the Boers who were then to the west of them. Du Moulin's men left Vlakfontein on 3 January 1902 and reached Luckhoff on the 11th. Griffin (6 January 1902) describes how they made that journey with stops at Metz, where they found 'traces of late occupation by Boers.' At Doornfontein on the Orange River, they were fired at from the opposite Cape Colony bank. At Du Plessis Dam the column camped at the place where the Boers had halted after the capture of Hamilton's baggage. Griffin (9 January) wrote that 'the well water is beastly and smells and tastes of horse' - evidence that the Boers had dumped a dead horse into it. Luckhoff was totally wrecked.

Pursuit

Into the Cape Colony they rode, crossing the border at Ramah's Spring, where they were 'most hospitably entertained by an English farmer' (Griffin's diary, 12 January). Even better was The Grange at Witteput (now Wiput) where Griffin recorded on 13 January that they played lawn tennis in the afternoon and went into the farm to 'hear some very feeble attempts at music in the evening.' At Belmont, site of one of the early battles of the war as Methuen advanced towards Kimberley, a patrol got in touch with 300 Boers moving south and, accordingly, followed them back into the Orange River Colony. (The British had annexed the Orange Free State and renamed it the Orange River Colony on 28 May 1900). Intelligence indicated that this commando was that of General Charles Nieuwoudt, in command of the district and under Judge J B M Hertzog. Griffin recorded that he was back in Luckhoff on 18 January and they had to stay there for the day to rest the horses, unable to move although they knew the Boers were only 10 miles (16 km) away. On 20 January, the men recovered thirteen mules and eleven horses near Liebenberg's Pan, some of Hamilton's losses.

Resupply was necessary and so the column headed to Fauresmith and then on to Jagersfontein. On the way, Griffin met up with Driscoll 'who had just caught 2 Boers and 250 sheep'. Griffin took the prisoners to Jagersfontein: 'I brought in 3 prisoners of Driscoll's', he wrote on 21 January, ie the two he had taken from Driscoll in the morning and then the brother of one of them, who had been given away after Driscoll had told his captured brother he would shoot him if his brother was not caught.'

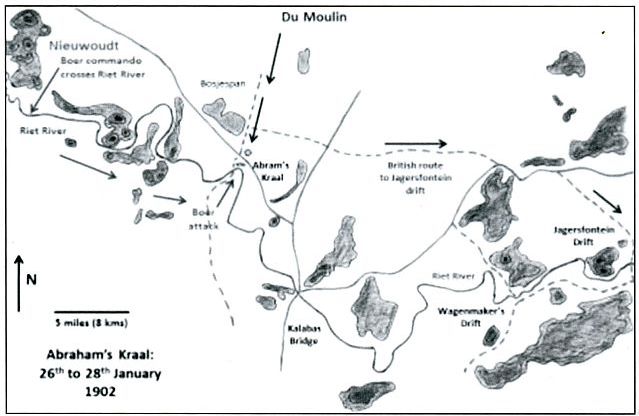

The Boers had moved north and, on 23 January, Du Moulin started after them. That night the column halted at Armoedsfontein and crossed the Riet River the following morning at Jagersfontein Drift. (Although this drift was referred to as Jagersfontein Drift on the north bank the river on the farm, Jagersfontein, the crossing point was almost certainly what is now known as 'Banks Drift' on an adjacent farm. That night, at Olievenkloof, it rained and Griffin (24 January) said it was 'the worst night I can remember'. The march took them to Tafelkop and, on the 26th they were at Klipnek in the afternoon, camping that night at Witdam, where there was evidently enough water for Griffin to have a bath!

On 27 January they marched west and at 08:30 four Boers were seen by the intelligence officer, Captain Beale, on the farm, Vaalpan, about 5 miles (8 km) away. Vaalpan belonged to Judge Hertzog. Griffin's horses were 'quite done up' and the Boers were watched from a high koppie (small hill). They circled around and joined a laager about 5 or 6 miles away. Griffin (27 January) estimated that 'there were about 400 Boers with 3 Cape carts [small, twowheeled, two-man carts with a canopy] and about 50 head of cattle and a lot of spare horses.' The Boers moved off and Du Moulin's men followed, passing through De Dam where the Boers had camped.

Abram's Kraal

By the evening the column was at the farm, Abram's Kraal, on the right bank of the Riet River with a low ridge between the farmhouse and the river. This is how Du Moulin (1907, p302) described the farm:

'At Abraham's [sic] Kraal, the farm houses are at the open end of a semi-circle some 200 yards [180 metres] in diameter, formed by a low ridge that rises here and there into small koppies covered with large stones. Beyond the buildings and facing the semi-circle is a garden with a stone wall. Standing with one's back to the garden and buildings, on the right is a large stone kraal divided into several compartments. In front is the highest part of the ridge, beyond which the ground drops very quickly to the Riet River. On the left, the ridge ends in a conical rocky mound, with a small kraal at its foot. On the outside of this mound a donga leads up from the river, and curls in towards the farm.' (The sketch map shows the marches of Du Moulin's column and the locations of the farms named).

The Boers, having crossed the river, were nowhere to be seen. They had circled .around to the west and were hidden in the hills around Poortjie. Their scouts told them of Western's column approaching from the west and they also knew that Driscoll was to their south. If they were to avoid encirclement they would have to attack one of them and Du Moulin's looked to be numerically inferior and closer at hand. Commandant M A Theunissen was given command of the attackers (In a footnote, Du Moulin, 1907, p 303, mentions that Nieuwoudt commanded a force of 400 men).

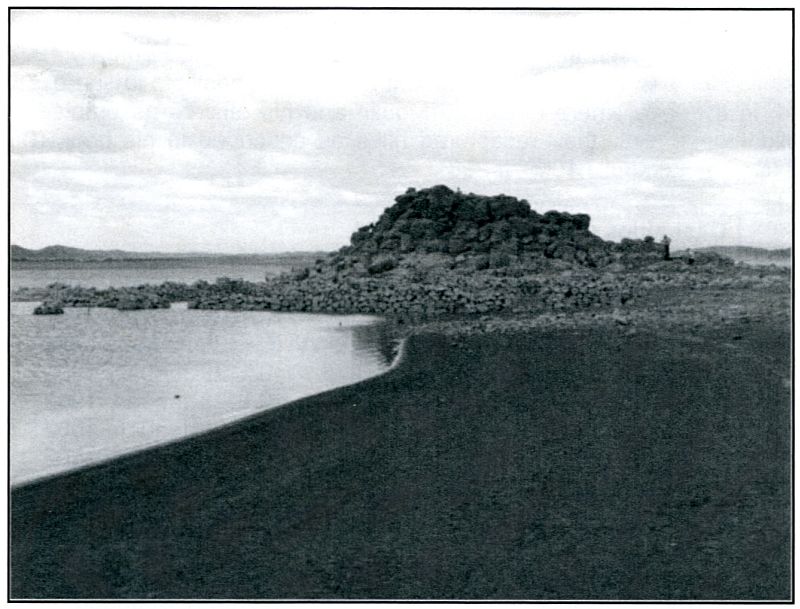

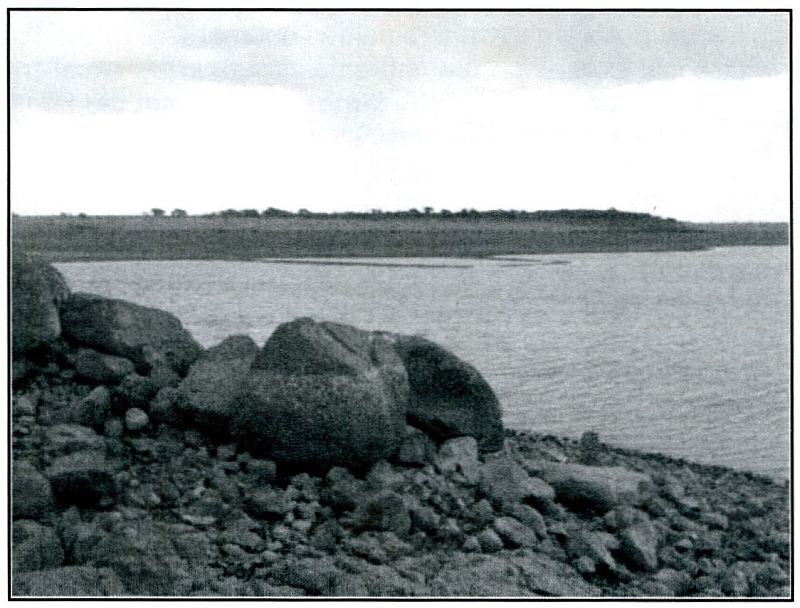

Kalkfontein Dam in December 2015, offering a rare glimpse

of the small kraal at Abram's Kraal, surprisingly well preserved.

The battle begins

Piquets were placed on top of the low ridge and on the left and right on small mounds. The colonel and his staff slept in the farmhouse and the other buildings were utilised by the men. The transport and the horse lines were along the garden walls. Fortuitously, at 01 :00, one of the Sussex's sergeants 'got up to put the nose-bag on his horse, as a patrol was to go across the river at 3 am.' He was walking back to his place when he heard a shot fired from the piquet and shouted, 'Stand to!' In the darkness, the Boers had climbed the steeper southern slope, but did not surprise the wakeful piquet, who saw them and one of whose members probably fired the shot. Crossing the drift at Poortjie, the Boers, had worked their way along the river bank until they were below the picquet. Some of them then climbed the steep southern slope of the ridge, and a number of them made it down the lesser northern slope and into the camp. Their guide, the owner of the farm, clearly knew every inch of the ground, but was killed early in the assault. The Boers occupied the large kraal coming around over the saddle to their left of the ridge. (A more detailed account of the attack is given in Du Moulin, 1907, pp 303-7).

Officers and men were quickly awake and soon recovered from the sudden shock attack. Major Gilbert moved to the small kraal where the pom pom was placed. Lieutenant Thorne was sent to the garden wall to get men to come over to the small kraal. These men maintained a steady fire along the ridge. Du Moulin collected together some of the other men who cleared the Boers out of the large cattle kraal. Leading a charge to clear the Boers from the further side, he was shot through the heart, and the two men following were mortally wounded. The British were now firmly established and fighting back. In his diary entry for 28 January, Griffin describes how he and two other officers were held at gunpoint as 'the bullets of friend and enemy alike were rattling among us.'

The Boers were then being contained and even pushed back, although the fighting must have been terribly confused. At about 02:00 Commandant Theunissen decided to call off the attack. A whistle sounded several times, apparently from the position of the piquet on the ridge - the signal to withdraw. Griffin's captors bolted and the Boers scrambled back over the drift, leaving two dead behind them. Griffin identified one of these as Field Cornet Myburgh. He does not name the other fatality, who was the owner of the farm.

Thirteen men died in the action; eleven men of the Royal Sussex Regiment, and two of their Boer adversaries. Seven of the British were killed in the action and the four others died later of their wounds. Eight of the Sussex men were buried at the farmhouse (the seven who were killed in action and Private Gaston, who was fatally wounded and died soon afterwards). Three graves were dug, one for Colonel du Moulin, another for the two sergeants and their men, and a third for the two Boers killed. 'At half past seven, all the available men paraded, Captain Montresor read the burial service, and the Last Post was sounded over the grave of the man to whose initiative and energy the column owed its existence, and who had died most gallantly in its defence' (Du Moulin, 1907, p307. LtCol du Moulin is described as a remarkable leader and organiser in the preface to his book, written in 1906 by a fellow officer of the Royal Sussex Regiment, Colonel J G Panton. The book was written by Du Moulin during his campaign in South Africa, but clearly not the final two chapters, describing Abram's Kraal and later.)

Sketch of the battle of Abram's Kraal, following

the description in De Moulin's Two Years on Trek

A major loss for the British at Abram's Kraal was the large number of dead horses and mules killed in the crossfire that had swept the horse lines in the darkness. (Estimates vary. Du Moulin, 1907, p 304 says 'ninety', while the Official History [Maurice, Vol 4, p 433] states 'nearly 150'.) The attack was abortive for the Boers - although they had killed a number of the column's animals as well as its commanding officer, they had lost two dead and a number had suffered wounds. One of the Boer wounded was serious enough that he was sent into the British camp under a flag of truce at 08:00, just as the column was leaving, though he later died (Du Moulin, 1907, p 308; Griffin's diary entries for 28 and 29 January 1902). There seem to have been a good many more wounded and later it was heard from prisoners that Nieuwoudt considered night raids to be too risky after his sortie at Abram's Kraal. Certainly, the Boers would never have attempted their bold assault in daylight. An attack timed to open just as dawn broke, as had been so successful for the British in night raids on Boer laagers, would have had a much better chance of success, rather than their desperate charge in total darkness.

Then began, at 08:30 that morning, the return to Jagersfontein Drift and Vlakfontein. Many of the men were dismounted but, nevertheless, the column marched nearly thirty miles (48km) and camped, according to Griffin's diary (29 January) 'at a farm about two miles (3.2 km) south of Jagersfontein Drift.' One of the wounded, Private B Gaston, died before the column set out. During the march, three more died and were buried along the way, one of them the wounded Boer. Privates Light and Clarke died on the journey and Brackpool on arrival at their camp on 29 January. (It has not been possible to establish exactly where they camped and exactly where the burials took place. Steve Watt's In Memoriam [2000] merely shows that they were buried in the 'Fauresmith District'.)

A number of African drivers had some adventures (Du Moulin, 1907, p308): 'Several of the African drivers had bolted at the first alarm in the morning, two of them with nothing on at all. They had made a bee-line through the barbed wire, cactus hedges and mud holes; and, during the march, sorry figures came limping back to the column and rejoined the wagons. One got right through to Vlakfontein, doing the 45 miles (72 km) in ten hours, and said the column had been wiped out. The garrison there had an anxious time until runners arrived from Major Gilbert [who had taken over command of the column] on the following morning.'

On 22 February, Griffin was back at Abram's Kraal, but remarked in his diary on that day that there were 'too many of our dead horses there to be pleasant'. The Royal Sussex Regiment was sent northwards and became part of Lieutenant-General Ian Hamilton's force in the western Transvaal. They took part in the actions in that area in April, just before peace was c.onciuded on 31 May 1902.

The battlefield today

In 1937 the Kalkfontein Dam on the Riet River was completed. The dam wall was built across the narrow neck between the hills at Poortjie. The Abram's Kraal farm was inundated by the water of the dam. Before the submersion, the remains from the graves at Abram's Kraal were disinterred and reburied on a hill near the dam wall. Only one metal cross remains, which bears the inscription: 'In memory of 9 British soldiers who died during the war'. This cross was probably moved from the original burial site to the Kalkfontein Dam cemetery and is still in place there. Nine might be an error as only eight were interred at the farm.

Kalkfontein Dam receding in December 2015 to reveal

some of the submerged battlefield at Abram's Kraal.

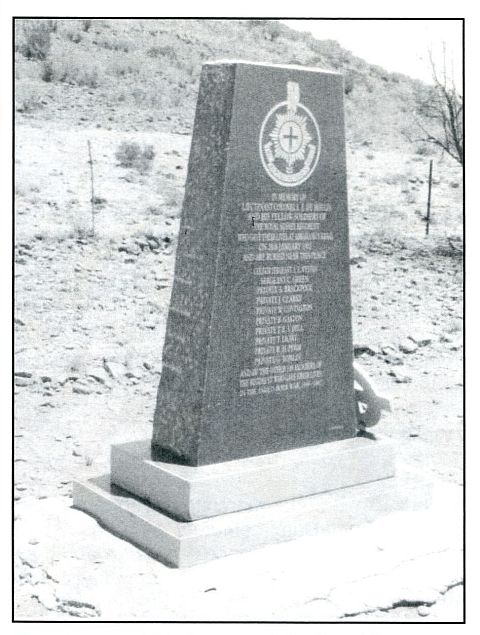

In 1983 the South African War Graves Board, in the person of Maurice Gough-Palmer, visited the Kalkfontein cemetery. Correspondence was opened with the County Archivist of the West Sussex Records Office, custodian of the records of the Royal Sussex Regiment, which was amalgamated with a number of others in 1966 and today forms part of the Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment. The South African War Graves Board expressed surprise that the Regiment had not erected any monument at Kalkfontein. The reaction from the West Sussex Archivist, in a letter from the West Sussex Records Office, dated 3 June 1983, was to the effect that the members of the Regimental Association 'will be delighted to know that this omission is being rectified'. In fact, it took another 25 years before the omission was finally rectified.

On 15 April 2008, a granite memorial was unveiled at Kalkfontein Dam cemetery by Brigadier Andrew Mantell, the British Defence Adviser in South Africa in the presence of a number of invited guests. The Regimental flag was flown out to South Africa in the diplomatic bag and The Royal Sussex Regimental Association was represented by former officers of the Regiment, Major Bazil Carlston and Captain Charles Wilmot. The project to erect the memorial was initiated and managed by a group of South Africans, led by David Scholtz. In a press release, the Royal Sussex Regimental Association expressed their gratitude for his work in doing this, which was described as 'devoted and imaginative'. It had not been possible to examine the actual battle site from 1937 until 2015, when the level of the dam fell to only 6.6% of capacity. Even so, the entire site was not above water. South Africa was experien cing one of her periodic droughts and this area of the country is particularly prone to the effects of drought. During a visit to the site in December 2015, the writer noted absolutely no flow at all in the upper reaches of the Riet River and recorded that it would take prolonged and incessant rainfall over some months to get it flowing again.

Granite memorial to the men of the Royal Sussex Regiment

who fell at Abram's Kraal, unveiled in a special ceremony on 15 April 2008.

When the writer and friends were taken to the site in December 2015 by Mr Attie Roodt, whose family own the farm Kraaipoort, the farmstead and most of the other buildings of Abram's Kraal remained submerged. Photos of what could be seen show the small kraal, in an excellent state of preservation, and the large kraal, but not the farmhouse or the walled garden. The slope from the camp piquet on the top of the ridge is quite gentle. The slope down to the river, although much steeper, would not, and indeed did not, offer a very difficult obstacle to the attacking Boers. A stone water tank, that appears on the knoll above the farmhouse, was clearly built after 1902. The top of the ridge behind the farm buildings, which was the site of the camp piquet, is always visible, even when the dam is full. It is then an island surrounded by water. As always, an appreciation of the real scale is only possible with a visit to the actual site. After so many years of waiting, it was a salutary experience to see the site of this fierce encounter between some determined Boers and their equally-determined British opponents. It may well be some years before such an opportunity to examine the site happens again

The Vlakfontein farmhouse where the British columns based themselves from December 1901 to February 1902 is, however, still intact. It is therefore possible to see exactly where Lt-Col du Moulin and his officers assembled to view their recaptured rifles as described in his book (Du Moulin,1907, p 298).

Casualties (Abram's Kraal)

| Lieutenant-Colonel L E du Moulin | KIA, 28 January 1902* |

|---|---|

| Colour Sergeant A E Weston | KIA, 28 January 1902* |

| Sergeant C Green | KIA, 28 January 1902* |

| Private W Covington | KIA, 28 January 1902* |

| Private T Hill | KIA, 28 January 1902* |

| Private R Pimm | KIA, 28 January 1902* |

| Private G Tomlin | KIA, 28 January 1902* |

| Private B Gaston | DOW, 28 January 1902* |

| Private J Clarke | DOW, 28 January 1902* |

| Private T Light | DOW, 28 January 1902* |

| Private A Brackpool | DOW, 29 January 1902* |

| Private T Bostock | Severely wounded |

| Private G Langley | Severely wounded |

| Sergeant E Simmins | Slightly wounded |

| Drummer S Sproston | Slightly wounded |

| Private J Coles | Slightly wounded |

| Private A Cox | Slightly wounded |

Casualties (Kok's Kraal)

| Lieutenant A Phillips (49th IY) | KIA, 25 December 1901 |

|---|---|

| Lance-Corporal H O'Donnel | KIA, 25 December 1901 |

| Lance-Corporal C Rigby | KIA, 25 December 1901 |

| Private B Bell | KIA, 25 December 1901 |

| Private H Darwin | KIA, 25 December 1901 |

| Private H Fort | Severely wounded |

| Private J Chalk | Slightly wounded |

| Private D Hart | Slightly wounded |

| Private J Ferris | Slightly wounded |

Bibliography

Du Moulin, Lt-Col L E, Two Years on Trek: Being some account of the Royal Sussex Regiment in South Africa (Murray and Co, The Middlesex Printing Works, London, 1907).

Childers, E (editor), The Times History of the War in South Africa, Volume V (Sampson Low, Marston and Company Ltd, London, 1907).

Griffin, Capt R C, typewritten diary in the records of the Royal Sussex Regiment, held in the West Sussex County Museum, Brighton, United Kingdom.

Kritzinger, Gen P, In the Shadow of Death (originally printed for private circulation in 1904, but is now easily accessible online through Project Gutenberg at www.gutenberg.org).

Maurice, Maj-Gen Sir Frederick, History of the War in South Africa, Volume IV (1906).

Watt, S A, In Memoriam (University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg, 2000).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org