The South African

The South African

Dawn. Dundee, Natal, 20 October 1899

It was bitterly cold. Indeed, it had uncharacteristically snowed the previous week. Huge banks of fog covered the town and surrounding high ground. Intermittent drizzle made everything clammy and miserable. Breath puffed out like a steam train. All in all, it was a time for any sensible person to be indoors, in bed. But all was not as peaceful as it seemed. Throughout most of the night, streams of Boers from the Utrecht and Wakkerstroom commandos had been stealthily occupying Talana Hill, a prominent landmark some two miles (3.2 km) east of Dundee, stumbling as quietly as possible over the slick, wet, rocky terrain until the summit was reached. It was their intention to rudely awaken the slumbering British garrison in the town below with the opening shots of the first major battle of the Anglo-Boer War.

Some few hundred yards to the south of Talana, members of the Middelburg, Vryheid and Piet Retief commandos had also taken up positions on a hill known as Lennox 3. According to Lieutenant Cecil Grimshaw, 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers: 'In the afternoon of the 19th October (Thursday) orders came in to us @ 3:30 to furnish a piquet of 12 men on the Landman's Drift road in the vicinity of the cross roads leading to Landman's Drift & Bart's Drift ... About 7 pm it began to pour I and we were all pretty well soaked through in an hour. Just about 8 pm my sentry on the road challenged someone who did not answer. He challenged twice, but still no answer. I rushed over to see what it was and luckily recognized Mr Robinson, one of our Intelligence Officers, with another man and 2 Bantu scouts. It was very well I did as the next moment he would have been shot as the sentry had loaded & I had drawn my revolver ready to shoot. I asked him why he had not answered & he said he, had passed my scouts & told them who he was & thought it was all right. He had never been given any "countersign" or anything, & if I had not happened to have known him from meeting him sometime before at polo it might have been a very serious thing. However, I learned from him that a force of Boers, about 200 strong, had moved across Malongeni Mountain about 6 miles (9.6 km) to my front, moving in a southerly direction'.

Had he but known it, the gun commander of one of the three Boer 75 mm artillery pieces, which had been back-breakingly manhandled up the slope, straining his eyes into the mist in an attempt to obtain a line of sight, was destined to meet the Regimental Medical Officer attached to the Royal Irish Fusiliers, then snugly snoring in his bed in the British army camp, under somewhat unusual conditions a couple of days later.

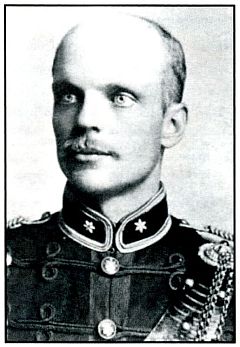

Mike du Toit, Transvaal Staatsartillerie

The Boer artilleryman was Lieutenant Michael Sievert Wiid (Mike) du Toit. In civilian life he had been employed by the Transvaal Surveyor-General's Department.

Engaged in the fighting during the Jameson Raid, he had joined the Staatsartillerie in 1897 and was immediately sent in command of an expedition to Swaziland. His grandson, Pierre, now living in Johannesburg, gave me the following information:

'On 20 October, over 100 years ago, my grandfather, Lieutenant Mike du Toit of the Transvaal Staatsartillerie, was wounded during the first battle of the war at Dundee in Natal. I have a photograph taken some years later showing him standing at the spot where he was wounded. I visited the site some years ago and due to the "skull-like" rock in the background was able to identify the exact position.

The summit was open veld without much cover but is today thickly covered with thorn bushes and trees. The Boer plan was to attack Dundee on three sides simultaneously at dawn on 20 October. Due to poor weather, the normal lack of discipline and the bickering of the Boer commanders, only General Lukas Meyer, with a force of about 2500, was in position on Talana and Lennox Hills and ready to attack at the prescribed hour. On Talana they hauled four guns to the summit but only positioned three before dawn: Two Krupp 75mm under Major Wolmarans and Capt Pretorius, and a Creusot 75 mm under Mike. The British camp was in plain sight below them and the first few rounds caused consternation. General Penn Symons remarked that it was "damned impudence to start shelling before breakfast!"

'Skote Petoors!'

This particular incident with the artillery led to the coining of the well-known Afrikaans idiom 'Skote Petoors', literally meaning 'good shot, Pretorius'. As already mentioned by Du Toit, Johannes Lodewicus ('Lood') Pretorius was in charge of the third gun of the Staatsartillerie at Talana. As the mist rose that fateful morning, crowds of burghers stood around their artillery pieces, encouraging the gunners to open the fight. Without taking the customary two sighting shots, Lood Pretorius put his second shot smack into the British camp. The Boers were delighted 'Skote Petoors!' one Boer shouted, and a new idiom entered the Afrikaans language.

The doctor

The British doctor in this story was Major Francis Augustus Bonner Daly, Royal Army Medical Corps. Major Daly was born on 28 May 1855 in Dublin. The family lived at 12 Russell Street. He was baptised on 20 June 1855 at St George's Parish Church, Dublin. Educated at Trinity College, Dublin, he gained his BA, MB and BCh. He was admitted as a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1887.

Appointed Surgeon, then Surgeon Captain, in the Army Medical Department in 1881, he served in Lt Gol Augustus Bonner Daly, Egypt in 1882 and with the Sudan Frontier Force from 1885 to 1886. He was Surgeon Captain in charge of the stationary hospital at Malipuram in 1892.

Promoted to Surgeon Major in 1893, he was appointed as Regimental Medical Officer to the Royal Irish Fusiliers and was stationed in Dundee prior to the battle of Talana.

Action

The Dundee Postmaster, H H Paris, had decided to sleep in his office and was rudely awakened by one of his clerks to be told that the Boers had commenced operations. They could be seen crowding the hills to the east of the town. Dressing hurriedly, the Postmaster was in time to see the first enemy shells overshooting the Post Office as the Boers tried to find the range of the army camp.

According to S B Jones of the Dundee Town Guard, in his Reminiscences of the Fighting at Dundee, [t]he next event was at 2 am, when shots were heard in the direction of Talani [sic]. At 2:30 am, more shots were fired, followed by one of the outlying military vedettes arriving at our' Guard Room [the Town Office] in an exhausted condition, minus his hat and coat, and covered with mud. He said that his horse had stampeded, and in the darkness [he] had lost the others. While talking to him, one of the mounted men of the same picket passed, galloping to the camp; immediately following this, one of the same party was carried to the Guard Room, having been shot through the groin. I had a stretcher brought out from the police quarters, and had the poor fellow sent on to the camp.'

, ... [With] the first streaks of dawn, when the "Dubs" [Royal Dublin Fusiliers] came marching down the main street to take up their position at the foot of the town, the KRR [King's Royal Rifles] marching in the same direction, but to our left, to take up another position. Everything remained quiet. At 5:30 I dismissed the men for an hour to go home for a change of clothes and coffee. Going home in company with my brothers and several others, we noticed that the hill "Talani" [sic] was swarming with men from end to end, and we were speculating as to who they were.' 'As we were partaking of our coffee, we were startled by the boom of a cannon, followed by the screeching of a shell which, to our intense surprise, burst and came rattling through the roof. We rushed out on to the verandah, overlooking the camp, when shell after shell came shrieking just overhead and, pitching into the camp, it dawned on us then that the first one had been a sighting shot ... With the boom of the first shot the rifle fire began, and I can only liken it to one of our up-country hailstorms rattling on the iron roofs.'

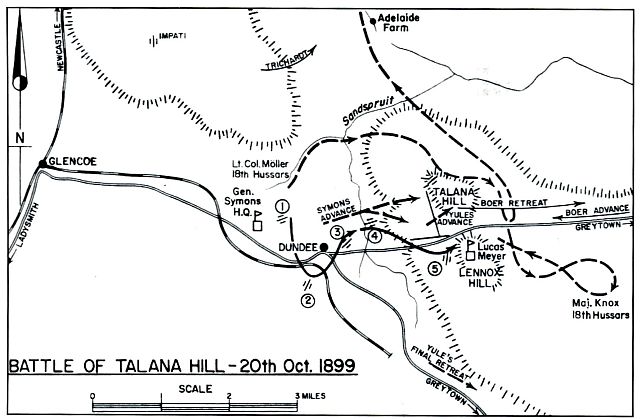

It is not the purpose of this article to go into the moves during the battle in any great detail. Suffice to say, British assault forces detailed to knock the Boers off Talana Hill comprised the 1st King's Royal Rifles, the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers and the 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers. The 18th Hussars were instructed to make their way to the rear of the Boer positions, and await their opportunity to mop up the almost inevitably retreating Boers. Three batteries Royal Field Artillery, the 13th, 67th and 69th, came up in support. The 1st Leicestershire Regiment were detailed as camp guards and saw no major part in the action. Colonial units included the Dundee Town Guard and Dundee Rifle Association, Natal Police, the Dundee Troop of the Natal Carbineers and a handful of Natal Guides. By and large, their job was to remain with the Leicestershire Regiment in the comparative safety of the army Camp.

The Dublin Fusiliers attacked the hill on the left flank or northern end of the assault line and worked their way up the hill using the cover provided by a deep gully. However, when they reached the mouth of the gully they found themselves pinned down under the guns of the Boers, literally sitting a scant few yards away on higher ground and firing almost straight down into their ranks. Their attack stalled, so the brunt of the assault fell by default upon the King's Royal Rifles and the Irish Fusiliers.

The battlefield

Talana Hill reaches upwards in a series of natural terraces, upon which Peter Smith had built stone walls so that he could graze his horses on the healthier higher slopes during summer, thus evading the ever-present danger of African horse sickness. These terraces, and the walls, provided plenty of cover and dead ground. The tricky part came when soldiers were forced to poke their heads up over a wall as a preliminary to an assault. The Boers, mostly crack shots from rural communities, awaited their opportunity and shot them down as soon as the British soldiers exposed themselves by climbing over the walls and rushing forward to the shelter of the next terrace.

Also adding to the discomfort of the assault force was enfilading fire coming in on the right or southern flank from the Boer forces stationed on Lennox 3 Hill. Having said that, however, supporting artillery fire assisted in keeping the Boers' heads down and these small rushes of infantrymen, covered by their mates, slowly but surely covered the ground towards the top.

BATTLE OF TALANA HILL - 20th Oct. 1899

Map by courtesy, Talana Museum, Dundee.

Lieutenant Robert Ernest Reade, posted to 'A' Company, King's Royal Rifle Corps, gives some idea of the difficulties encountered by the assault forces. Deploying to what is now the Steenkoolspruit, on the eastern edge of Dundee, he noted that: 'the bullets began to fizz around us ... a wood of gum trees ... stretched most of the way along the foot of the hill ... the way up from the spruit to the wood was an absolutely open space. The wood was about 200 yards [183 metres] deep, then there was about 150 yards [137 metres] to a stone wall, running all along the hill, along which, on the other side from us, the Boers were thick. Then 50 yards [46 metres] off, fairly steep ground, the last seventy yards [64 metres] to the top almost a precipice.'

'The Dublins got across the open space and lay down behind the ditch on this side of the wood. Then came our turn to do exactly the same thing. This we did at a slow double. The bullets were as thick as an ordinary hailstorm, and it seems to me almost incredible that we only dropped about thirty men on the way. I was dimly conscious of many bullets passing over my head and, in particular, a succession of bullet after bullet just behind the nape of my neck. I am inclined to think that, as my equipment was still rather bright, some old veteran Boer had singled me out as being an officer.'

'We reached the ditch and soon advanced to help the Dublins. We got the order to advance up the hill by the side, of a stone wall running up the hill. While sitting behind the bank, two poor Tommies on either side of me were shot, as the bank was really no shelter - the men were falling all around, and the groans of the poor fellows were terrible. I saw Pechell standing up looking out to see if it would be advisable to move further to the left - the bullets were coming thick allover the wall, which was only about three feet [0.9 metres] high, and the next moment he was down. Boultbee and I, who were near, ran down to support him, but it was almost allover with him. I shall never forget that minute - it was about the worst in my life. While we were holding him up, one on each side, Boultbee suddenly put his hand to his side - he was wounded, and badly too. By this time it was all over with poor Pechell, so we had to get Boultbee as comfortable ap possible.'

'The fire was now hotter than ever, and all I could do [was] to fire volleys now and then [over the wall]. On one occasion, as I was looking over the wall with my helmet off, there was a rather near fizz, and then I felt a little dazed, but did not realise what had occurred until two or three Tommies on either side of me said "That was a close shave, Sir, through your hair."

Lieutenant Reade, with his half-company on the extreme left of the' line, was not even aware that the final charge had been made until it was all over: 'When almost at the top we caught sight of them, and at the same time out rushed about 20 old Boers who, standing on the skyline, took shots from only about 10 yards [9.1 metres] distance at our leaders, all of whom they either killed or wounded, until they themselves [were despatched] by the hail of bullets sent from below. Thus died our Colonel [Gunning] and many of our officers and men. On seeing the charge I ran around into the centre to try and get into it, but when I got there the artillery had already started to play on the brow again. By a dreadful mistake, they showered some of their shrapnel on the brow near the top where our poor wounded fellows were lying.'

This unfortunate incident came about as a result of the artillery being unable to differentiate friend from foe once the assault line hit the crest. Only a gallant dash by a young signaller, Private Flynn of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, down the hill, and indignant remonstrations with the battery commander, stopped the slaughter.

The response

According to The Times History of the War (Volume II, pp 156, 158), the first response to the Boer artillery fire from Talana Hill came from a British battery, 67th Battery, Royal Field Artillery, which 'opened fire with splendid promptitude and strewed the slopes of Talana with its ineffective [out of range] shrapnel. The rearing and plunging horses were hooked in. While the 67th Battery unlimbered in the gun park and fired the shells [which] fell short of the Boers on the hill, the 13th and 69th advanced to get within effective range. The guns, with their straining teams, came thundering through the outskirts of Dundee and unlimbered on a knoll to the south of the town. A minute of rapid movement, a hell broken by the hoarse orders of the section commanders and the cracking of driver's whips ... the 69th ... came into action at a range of 3 650 yards [3 336 metres], barely ten minutes having elapsed since the first Boer shells were fired.'

A section of the 67th Battery RF A was credited with firing the first shots from the British side in the war. Unfortunately, the Battery was then tasked with defending the British Army camp, and took no further part in the battle.

At this early stage in the battle, Lieutenant du Toit of the Staatsartillerie had managed to hit the British camp with commendable accuracy, but had not caused too much damage as the ground was soft and the shells appeared to have been incorrectly fused and most failed to explode. On the British side, Lieutenant Osmund Charteris du Port, DSO, of the 67th Battery was wide awake and managed to fire off the first retaliatory shots, but his guns were out of range and inflicted no casualties on the Boers. It was thus a somewhat inauspicious start to the day for both of these artillerymen.

The Boer hospital

On the Boer side, Mike du Toit's day did not get any better. His grandson, Pierre, explains: 'The battle was fierce and bloody with the British succeeding in driving the Boers off Talana when the other commandos failed to attack. Mike was wounded in the leg by a piece of shrapnel and carried "piggy-back" down the back of the hill by his friend F L Rothman, where he was transferred to an ambulance and on to a farmhouse where the Boers had established a hospital'. (This is now Thornley Farmhouse, owned by the late Peter and Bernice Grant, direct descendants of the original owners).

According to Dr George Moorehead, a British doctor working for the Red Cross and attached to the Boer forces, '[t]he farmhouse, a solid building, surrounded with stone walls and stone offices, which had belonged to a farmer named Smith, presented an extraordinary appearance. The yard was full of horses standing patiently with their bridles hanging down and their saddles glistening in the rain. Boers in every possible state of mind were crowded about - some stood talking; some rushed about; others sat quietly against the walls eating tinned food; some had their bandoliers and rifles while others had neither and were hastily pinning on bits of red rag to their arms or begging us for Red Cross badges. Wounded men were being helped in by their friends, carried down in blankets or overcoats. Boers were constantly arriving from the hills above, on which the rifles still cracked out. Shrapnel whizzed noisily overhead now and then. All looked angry and frightened.'

'I stepped into the house. Right opposite me, crumpled up in the passage, lay the body of Field Cornet Joubert of the Middleburgers, a little round hole in the centre of his four-coloured hatband. A room to the left was full of sopping wet and wouhded Boers lying about in every attitude. In a room to the right the little German artillery doctor welcomed us warmly ... on a large bed lay Lt du Toit, with whom I had ridden a couple of days previouslyhis leg shattered by shrapnel. Beside him lay an artillery private, shot through both lungs ... the floor was covered with wounded ... pools of water and blood lay everywhere. Lt du Toit told me that he and an artilleryman named Schultz had alone worked a Krupp and a Pom-Pom until they were both struck down at the same time.'

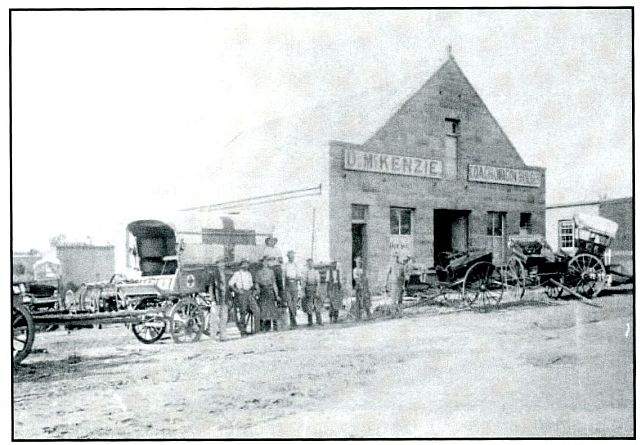

British casualties were tended to in various dressing stations and cottage hospitals in Dundee. In his diary (p78), the Reverend Bailey records that 'the buildings of the Swedish Mission were very suitable. There are in the compound a church and some half dozen cottages. This hospital was initiated, I understand, by Dr Galbraith, Messrs Brokenshaw [Brokensha], Arnot, and others. I must not forget the Rev J E Norenius, the missionary in charge; he placed his buildings at the services of the military and worked hard to make the hospital a success. The officer in charge of the hospital was Major Daly, RAMC, and he had an admirable assistant in Dr Galbraith of Dundee.'

However, once the decision had been taken to abandon Dundee and fall back on Ladysmith two days later, the patients in the various hospitals had to be abandoned. The Rev Gerard Bailey noted that the town fell at 13:00 on the afternoon of 23 October. General Penn Symons died on that same day, and was buried the following day by Bailey at St James' Church: 'There were of necessity few to do honour to his burial. There were some of the Royal Army Medical Corps (including Major Daly), and an officer of the 60th King's Royal Rifles, and a few townspeople. This body, which was sewn up in a Union Jack, was carried into the church and laid before the alter for the first part of the service. It was difficult to realise we were burying a General. Those that were buried in the grounds of the Swedish Mission, where the hospital was, numbered [fifteen]. Major Daly, Royal Army Medical Corps, had this graveyard well fenced and cared for.'

Looting

Denys Reitz describes how the town of Dundee was well and truly ransacked by the occupying Boer forces: 'Soon 1 500 men were whooping through the streets, and behaving in a very undisciplined manner. Officers tried to stem the rush, but we were not to be denied, and we plundered shops and dwelling houses, and did considerable damage before the commandants and field cornets were able to restore some semblance of order ... the joy of ransacking other people's property is hard to resist, and we gave way to the impulse ... we brought away enough food for a royal feast. There was not only the town to be looted, but [also] a large military camp standing abandoned on the outskirts, and here were entire streets of tents, and great stacks of tinned and other foodstuffs ... comfortable camp stretchers and sleeping bags, and even a gymnasium.'

The Reverend Bailey confirms Reitz's account: 'The Boers began looting right and left. [They] were like a lot of wild schoolboys loose in a fruit orchard ... we quite expected the seizure of liquor and all the foodstuffs, but what we did not expect was the wanton destruction of properties and belongings in stores, offices and private houses ... the work of destruction was so rapid and violent that it was little use protesting. [In one particular restaurant] they helped themselves wholesale to the liquor, seized his whole stock of cigars, smashed up a new cinematograph, wrenched the action out of the piano and demolished several musical instruments. We hoped that private houses would be safe from their pilfering. But no such luck. There were those who entered the houses and out of pure wickedness smashed and broke up everything they thought fit, even going so far as to wrench mantelpieces from their place and break them up. Other came with wagons and carted furniture away wholesale [plus] linen and clothes.'

Percy George Hill, in his diary, notes that '[I]ooting now began. Hotels, shops and bars were broken into right and left. By Tuesday there was not a suit of clothes, shirts, boots, saddles or spurs to be had in the place. Their Magistrate was a mere boy of about 27, but his assistant, Beyers, and his jailer, Nel, had as much to say as himself. They had their office at the local Board and lived in Sgt Smith's house. All the banks were broken into. The Natal Bank safe was carried off. The streets were littered with papers, broken bottles etc. Carts and wagons were taking away furniture. The natives assisted the Boers as well at the start, but later on they were all made prisoners and put to work to clear up the dirty streets.'

The British Field Hospital fared little better. However, the decision to leave Major Daly behind to look after the wounded had been well made. He was an unorthodox and inspirational leader, as extracts from some of his confidential reports show: 'very zealous, good ability, looks after his patients with much care and devotion (1892)'; 'Wanting in tact. Impetuous and excitable'; 'an excellent, zealous, conscientious & thoroughly reliable MO (1897)'; 'Has done excellent work in difficult circumstances. Has great ability and energy. General Buller complains somewhat of his address and manner (8 October 1900)'.

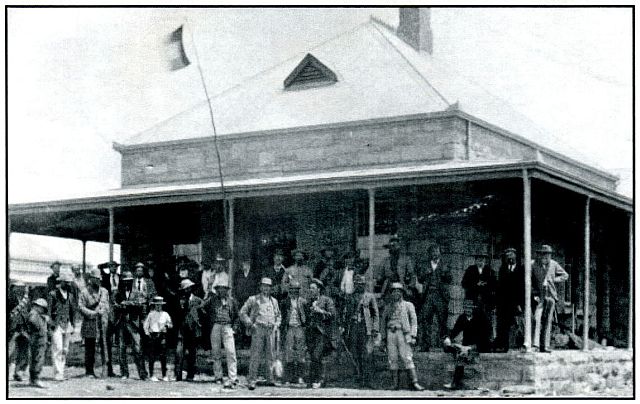

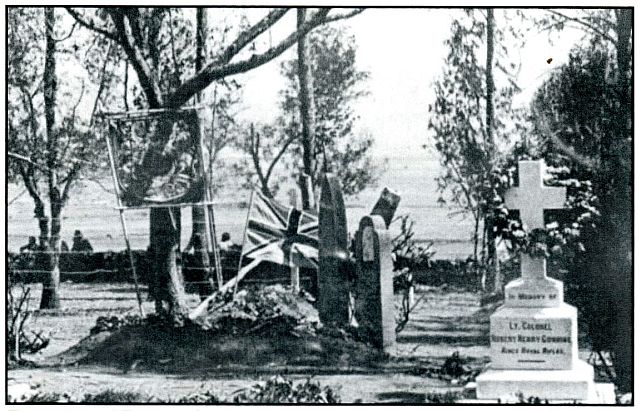

The original Talana Cemetery,

with Lieutenant Gunning's grave in the foreground

(Photo: By courtesy, Talana Museum).

Major Daly's first priority was to have the abandoned British camp and deserted town scoured for provisions for his personnel and patients: 'On my return to the mission I got a great surprise. Sixteen men of the Town Guard of Dundee had turned up fully armed and with two boxes of ammunition. These I ordered them to bury at once, and to hide away their rifles in some outhouse. Now, as these men all knew the run of the town, I ordered them to go there at once, and bring me back a supply of bread, sugar, tea and tinned foods, and they returned with a good haul. I was all right for the night; all the wounded were washed, fed and cared for, but they still only had the floor to lie on.'

'The medical and surgical panniers my natives had brought in from the battle area, and from them I got medical and surgical dressings. Everyone worked hard all day and night, and by that time I had stored sufficient food for 200 men for six months. The other section of my staff had obtained bedsteads for all the sick and staff, also bedding and clean clothes for the sick. In my search of vacated private houses I got all kinds of luxuries, such as pillows, bedspreads, crockery, glass lamps, kerosene and an excellent typewriter.'

'A large number of armed Burghers crowded into my hospital. At first they would not believe that the sick men were British soldiers ... and they intended to shoot every one of them. Finally I convinced them that they were really British soldiers. They then asked for their own wounded, and I had several of them in this same ward dovetailed between our men. These they questioned closely, and when they found that they had received every care, exactly the same as our own men, the Boer commander at once became civil, and thanked me.'

'Towards the end of the first week I was asked to a Boer camp to inspect an artillery Boer officer (this is where Lt du Toit returns to the story) who was badly wounded, and the Boer doctors wished to amputate his leg. I consented. On arriving at the Boer camp [at Blood River], situated at about 10 miles [16 km] from Dundee, I examined the wounded officer. I assured him that if he came to my hospital at Dundee I would save his leg. This he gladly accepted, and the next day I had him brought in. He turned out a great asset, as through him I could get any extras I applied for. On November 10, 1899, the condition of this Boer officer was so improved that he was fit to travel. So a special train with an ambulance carriage conveyed him to Pretoria. Before leaving he obtained for me a flock of 297 sheep.'

'I am sure on his return to Pretoria this Boer officer must have spoken very highly to General Botha of what I had done for him. About 10 days afterwards Chris Botha, a brother of General Botha, arrived with a present for me of a splendid pair of koodoo [sic] horns from the largest animal ever shot in the Transvaal. Also a letter was sent asking me to "accept the same as a token of goodwill during the occupation of Dundee by his forces". These horns General Botha prized very much, having them hung up in his house for seven years. Some years ago I presented these horns to the Australian Club, Melbourne, where they will remain for all time. They were measured with those at South Kensington Museum, and they have proved to be world size.'

So ended a fleeting and somewhat curious relationship between the artilleryman and the doctor. The doctor saved the artilleryman's leg and, in return, earned the goodwill (and provisions) of the Boers, as well as a record-breaking set of kudu horns. Lt Col Daly CB, BA, MB, BCh, FRCS remained in South Africa after the Boer War, being stationed at Standerton for some years. Posted home on 28 July 1908, he was placed on retired pay on 14 April 1909. He died on 8 May 1946 at Erin's Rest, Portsea, Australia.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amery, Leo (Editor), The Times History of the War in South Africa, Volume II (Samson Low, Marston & Company, London, 1909).

Daly, Lt Col F A B, Boer War Memories: Personal Experiences (Wilke & Co, Melbourne, 1935).

De Villiers, J C, Healers, Helpers and Hospitals: A history of military medicine in the Anglo-Boer War (Protea Book House, Pretoria, 2008).

Reitz, Denys, Commando (Faber and Faber, London, 1929).

Rundgren, Pat, The Colonials at Talana (Stok's Systems, Dundee, 2011).

Talana Museum Archives, Dundee.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org