The South African

The South African

On 29 September 2017, twenty learners from Hoërskool Waterkloof, Pretoria, visited the battlefields to pay tribute to South Africans who lost their lives in the Third Battle of Ypres during the First World War.

The infamous Third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, was one of the bloodiest battles of the First World War. The Germans call it the 'Flandernschlacht' (the Battle of Flanders) (Lloyd, 2017). In the summer of 1917, fighting on German's eastern border had stopped due to the Russian Revolution and it was possible to redeploy German troops to the west. Faced with this imminent surge in German military strength, Britain knew it had to act quickly. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig developed a plan, the main aims of which were to reclaim the high ground at Passchendaele and to push the Germans back from the coast in order to destroy their submarine bases. Their U-boats continually threatened Britain's supply line and the American reinforcements arriving by ship (Ruler & Thomson, 2014).

On 31 July 1917, Field Marshal Haig sent Allied troops 'over the top', ie out of the trenches towards the enemy, but a few days later the heavens opened and the worst deluge to hit the region in 30 years turned the Flanders fields into a quagmire. Tanks got stuck; gun mechanisms jammed and crater holes that used to provide shelter from enemy fire filled up with water. Men and horses drowned in the worst sections. Haig called off the attack, but stubbornly issued another on 16 August, others again on 20 and 26 September, and another on 4 October.

By the time Allied forces reached Passchendaele on 6 November, 325 000 Allied and 260 000 German troops had lost their lives over five miles (8km) of land. To give a sense of the scale of the loss, it is estimated that for every square metre gained, 435 men died (Ruler & Thomson, 2014).

In an attempt to gain an advantage before American troops arrived in Europe, the German Army embarked on the Lys Offensive in April 1918 and, in the space of three days, pushed the Allies all the way to the outskirts of Ypres, reoccupying the land taken by the Allies during the Third Battle of Ypres.

The Centenary commemoration of the Third Battle of Ypres was on everyone's mind when 20 learners of Hoerskool Waterkloof in Pretoria, their teachers, and their Belgian Guide, Filip Debergh, departed from Bruges to the different battlefield sites on 29 September 2017. The previous day, the learners had attended a two-hour lecture on South Africans' involvement in the First World War at the Sint-Leo Hemelsdaele Secundaire School in Bruges. The learners gained valuable insights into the reasons for the War, the countries in which South African soldiers had fought, what it meant to 'hold at all cost' at Delville Wood, the atrocious conditions in the Battle of Passchendaele, the full extent of all South African involvement in the war, especially the tragedy of the South African Native Labour Corps (SANLC) on board the SS Mendi, and the South African soldiers' mascots, Nancy the Springbok and Jackie the Chacma baboon. Filip, our guide, selected the various places to visit, since there are approximately 176 cemeteries of the Great War alone around Ypres!

Tyne Cot CWGC Cemetery

Our first stop was the Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) Cemetery. 'Tyne Cottage', a barn named by the Northumberland Fusiliers, its appearance reminding them of their homes back in Britain, stood near the level crossing on the Passchendaele-Broodseine road. It was captured on 4 October 1917 in the advance on Passchendaele. A German blockhouse or 'pillbox' was used as an advanced dressing station after the battle. This pillbox and three others remain in the cemetery today. By the following March, 343 graves had been made in an irregular pattern around the pillbox. The cemetery was greatly enlarged after the Armistice, incorporating the Fallen from the battlefields of Passchendaele and Langemarck.

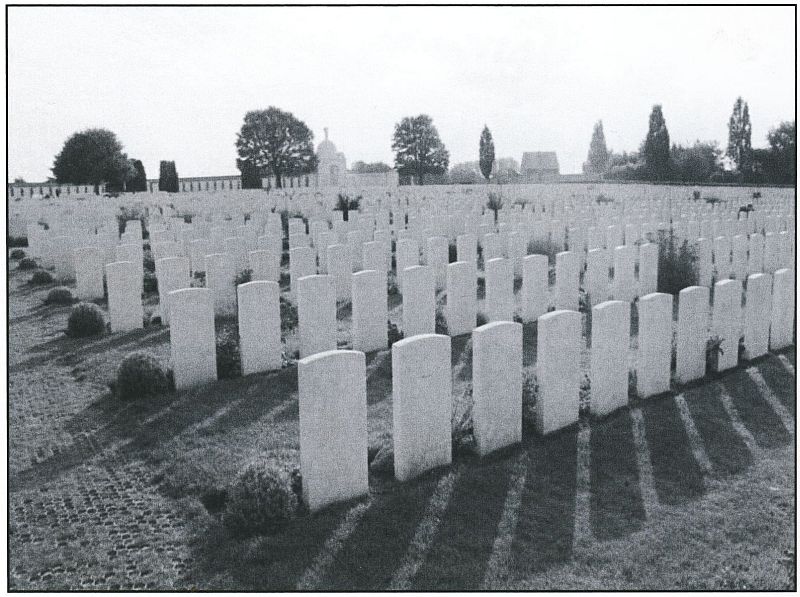

Tyne Cot Cemetery is the largest Commonwealth war cemetery in the world, with almost 12 000 graves. The cemetery includes four German graves. The seemingly endless rows of gravestones made a powerful impression on the learners, especially as more than 8 000 are graves of unidentified men. The Cross of Sacrifice was built upon the ruins of one of the imposing German pillboxes. Tyne Cot Memorial commemorates a further 35 000 British and New Zealand dead who fell after 16 August 1917, most of them during the Passchendaele Offensive. When King George V visited Flanders in 1922, he asked poignantly whether there could be 'more potent advocates of peace upon earth through the years to come than this massed multitude of silent witness to the desolation of war' (Lloyd, 2017).

Filip Debergh also explained the function and methods of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. After the war, all the burial sites were reorganised and the wooden grave markers were replaced by white Portland headstones. They are all alike in shape, colour and height. Every soldier has his own grave and there is not any distinction in the tombstones of different ranks. Every stone displays the soldier's regimental badge. For most Commonwealth soldiers, the national emblem is used, such as the maple leaf for Canadians and fern leaf for New Zealanders. The tombstone also records the soldier's name, rank, date of death, age, and often a religious symbol. All tombstones J are identical except for short and carefully monitored lines that relatives could add at their own expense. The soldiers were buried as near as possible to the place they had fallen. To see the thousands of epitaphs, 'A Soldier of the Great War known unto God,' made a huge impression on the learners. They also learned that reburials still take place today. Our guide showed us some of the South African soldiers' tombstones with their characteristic Springbok heads.

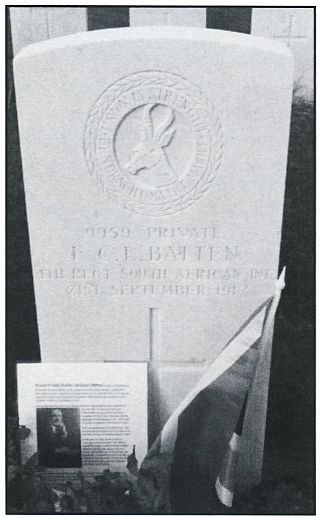

The learners visited three graves of unknown South African soldiers whose remains were discovered on 23 September 2011. The insignia identifies them unmistakably as South Africans and the artefacts are kept at the Memorial Museum Passchendaele (Van Wyk, 2014). The three soldiers were re-buried on 9 July 2013. A learner placed a small South African flag at their graves. We also visited the tombstone of Private Ernest Charles Lambourn Batten, a music professor who served with the 4th South African Infantry. Filip Debergh gave a short overview of Batten's life and his involvement in the war. He was 41 years old and died on 21 September during the Battle of the Menin Road (Digby, 1993). A national flag was placed at his grave and the learners sang the national anthem.

We were very impressed by the immaculate condition in which the cemetery is kept. The lawn is perfectly mown and roses and other perennials flower abundantly, as if in an English park. Two horticulturists were cutting roses growing on some of the soldiers' graves while we were there. The numbers of visitors to Tyne Cot Cemetery is astounding.

The Scottish and South African Memorial, Frezenberg

The next stop was at the Scottish and South African Memorial near Frezenberg. This monument commemorates all people of Scottish origin who took part in the Great War. On 20 September 1917, another stage of the Battle of Passchendaele took place. The plan was to capture the Gheluvelt Plateau. At 5:40 the South African Infantry Brigade attached to the 9th Scottish Division assembled in their front positions near Frezenberg, 2 km west of Zonnebeke, and advanced in the direction of Zonnebeke, behind a screen of smoke and curtain of creeping barrage. The churned-up landscape was littered with wrecked tanks, shattered trees and treacherous, waterfilled shellholes.

Belts of barbed wire protected the massive defensive fields of concrete blockhouses (pillboxes) from which the hail of rnachinegun fire swept the low ground. Lance Corporal W H Hewitt captured one of the pillboxes single-handedly and received the Victoria Cross for his exploits. It took three hours for the four South African regiments to reach their assigned objectives, but at a high cost. Of the 2 576 men who had started the attack, 1 255 were listed as killed, wounded or missing (Debergh, 2017).

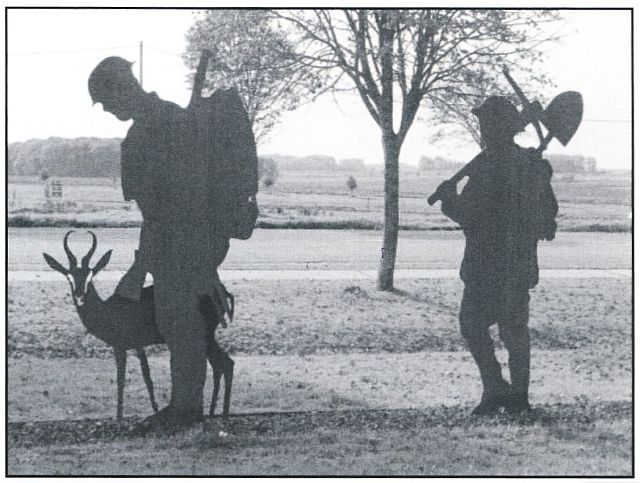

For the 2017 Centenary of the Scottish involvement in the Passchendaele campaign, a new project was erected under the title 'The Long Road to Passchendaele'. A line of corten steel silhouettes was installed: soldiers marching past the Scottish Great War Memorial through the former battlefield towards Passchendaele (Debergh, 2017). The chronological order of unveiling the steel silhouettes was done in accordance with the countries' involvement. Two of the silhouettes are of South African soldiers. One is of a soldier of the 1 st South African Brigade; the other is of a soldier of the SANLC. Other soldiers represented in the steel silhouettes, from Scotland, Australia and New Zealand, were already unveiled. At the time of our visit, the Canadian soldier still had to be unveiled. The statues have been inspired by the many soldiers who marched to the front at this very place and are based on photographs of famous war photographers such as Ernest Brooks, Frank Hurley and others. As such, they also pay tribute to these photographers (Debergh, 2017).

One feels proud to see the South African flag flying among those of the different nations that were involved, the silhouettes from South African soldiers and the new plaque that was unveiled on the monument, donated by the South African Government.

Hill 60 and Caterpillar

When we stopped at Hill 60, I could clearly see the improvements made to the site from 10 years ago. There are new information boards, as well as wooden walkways (Van Wyk, 2007). The number of visitors was also substantially greater, despite a new admission fee. Maybe it was because we were having good weather. The learners found it amusing that even though they were prohibited from certain areas due to the dangers of old military munitions which might explode, sheep were being used there to keep the grass short!

The Battle of Messines (7 to 14 June 1917) was fought by the British Second Army. The tactical objective of the attack was to capture the German trenches and fortifications on the 76m high ridge which dominated Allied positions to the south of Ypres. Because of its strategic views, man-made Hill 60 and Caterpillar saw some desperate fighting. On 7 June 1917 the British detonated 32 tons of explosives in 19 of the 21 mines placed in tunnels under German positions. The explosions were so loud that they could be heard in south-east England (Willmott, 2012)! General Plumer commented: 'We may not win the battle, but we will change the geography,' (De Vries, 2007). Thousands of soldiers lost their lives in this area and subsequent fighting made it impossible to recover or identify most of the dead at the end of the war. Filip showed us some German bunkers near Hill 60. The German bunkers that still litter Flanders will last an eternity, while those built by the British are crumbling away (De Vries, 2007). It was a pleasant walk around the huge crater, but some learners were horrified to learn that it was caused by the most violent explosion used against people before the dropping of the first atom bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, on 6 August 1945!

Bayernwald (Bavarian Wood)

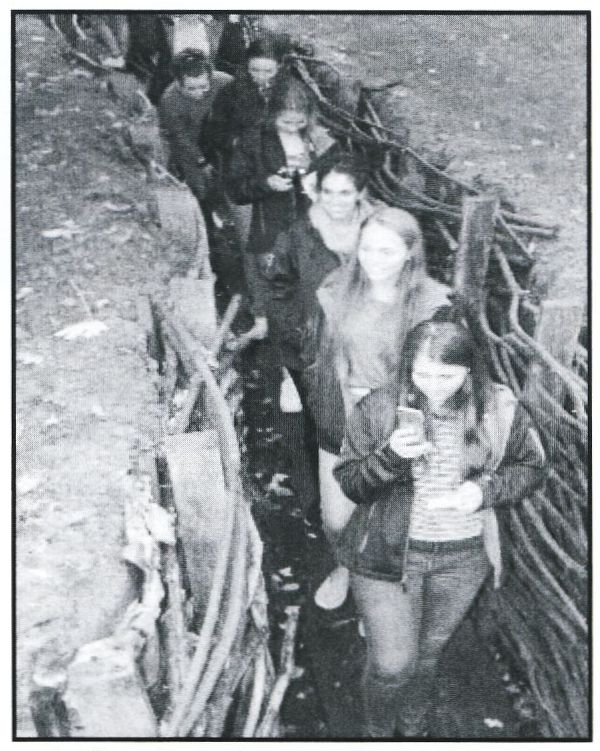

An entire tourist industry has sprung up around this site of the First Wold War, where an admission fee has to be paid to get access the trenches. Roughly one kilometre north of the tiny village of Wijtschate, are located the German trenches of Bayernwald. This elevated wooded ground, 40 metres above sea level, was won by the Germans after fierce fighting and was a key site during the Battle of Messines. The Germans developed an impregnable system of trenches, bunkers and mine shafts, but today you can only see about ten per cent of what was there during the war. It was interesting for the learners to hear that Adolf Hitler had served here in 1914/15, and was awarded an Iron Cross close by while working as a Company Runner. He returned to visit the site in June 1940, following the fall of France during the Second World War (Debergh 2017). The name of the soccer club Bayern Munich now made much more sense to the learners after the visit to Bayernwald!

In Flanders' Field Museum

In Flanders Field Museum is in Ypres, dedicated to the study of the First World War. It occupies the second floor of the Cloth Hall on the market square in the city centre. The building was largely destroyed by artillery during the war, but was later reconstructed. In 1998 the original Ypres Salient Memorial Museum was refurbished and renamed In Flanders Fields Museum after the famous poem, In Flanders Fields, by Canadian doctor, John McCrae.

The display on the role of horses during the First World War was both impressive and sad. It was interesting to see tobacco products from both South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), which were given to the soldiers as presents. The tobacco product from South Africa was called Springbok Brand.

Corporal Albert Johannes Loubser, buried at Dozinghem Military Cemetery

Many cemeteries in the Salient still bear the original soldiers' names. A few kilometres to the north-west of Poperinghe is the casualty clearing station cemetery, wryly called Dozinghem Cemetery, in imitation of a Flemish place name. The cemetery was started in July 1917 during the Third Battle of Ypres. In this cemetery, Corporal Albert Johannes Loubser, 4152, 1st SAI, DCM, is buried. He died of a wound on 17 October 1917. His official remembrance was held here at 17:15 on 29 September 2017, the initiative of our guide, Filip Debergh, a VIFF (Friend of the Flanders Field Museum) member, who specialises in South African involvement in the First World War. Before the official ceremony, a national flag was placed at the grave of each South African soldier who was buried at Dpzinghem Military Cemetery. There were also graves with Irish, British, American, Canadian and Australian flags,and some graves of soldiers who died during the Second World War.

The service was conducted in three languages: Flemish, English and Afrikaans. Readings came mostly from Peter Digby's book, Pyramids and Poppies (1993). Filip Debergh, as Master of Ceremonies, and two learners from Sint-Leo Hemelsdaele Secundaire School, gave some background information about Corporal Loubser. For conspicuous gallantry during operations, he showed the greatest devotion to duty and, as a stretcher-bearer during three consecutive days and under heavy shell fire, he carried in two severely wounded men.

The main address was by South African Assistant Defence Attaché in Belgium, Lt Col Andrew Mafofololo. In his speech, he emphasised the importance of recognising the involvement of all South Africans during the First World War. After the speech, several learners read extracts about Corporal Loubser's life.

Fourteen other South African soldiers were remembered at the ceremony:

Private Arthur John THOMSON, 34 years old, from Surbiton, Surrey, who died on 19 October 1917; Private Alfred Edward NEWMAN, 17 years old, from Johannesburg, who died on 20 October 1917; Private Ronald Erskine PARSONS, 23 years old, Jfrom George, Cape Province, who died on 18 October 1917; Private Sydney Herbert MEAD, 20 years old, from Gwelo, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), who died on 20 September 1917 at the battle of the Menin Road; Lance-Corporal Frantz METH, 27 years old, from Tabankulu, East Pondoland, who died on 26 October 1917 and whose brother, John McKenzie had been killed, three months before, in the Somme, France; Private Harry LOWE, 18 years old, from Forest Hill, Johannesburg, who died on 30 October 1917; Private Victor Christmas CAMPKIN, 25 years old, from Thetford, Norfolk in England, who died on 23 September 1917; Private Matthys Daniel Andries CECIL, 19 years old, from Shannon, Bloemfontein, who died on 14 October 1917; Private Frederik Martin FOLEY, 24 years old, from Rebecca Street, Pretoria, who died on 21 October 1917; Corporal Theodore HAGGLUND, 27 years, from Knysna, Cape Province, who died on 22 October 1917 and whose brother, Victor, was later killed near Beaurevoir, France, in October 1918, both mentioned on their parents' grave at Maitland Cemetery, Cape Town; Private George Henry KING, 23 years old, from Franshoek, Cape, who served in the South African Railway Overseas Dominion Service and died on 28 September 1917; Corporal Roland John LAWRENCE, 40 years old, from Bezuidenhout Valley, Johannesburg, who died on 15 October 1917; Private James Benham ALLAN, 33 years old, from Durban, who died on 16 October 1917; and Private Colin McLean BEATON, 22 years old, from Balmoral Street, Cape Town, who died on 20 October 1917.

The Exhortation from For the Fallen, by Laurence Binyon, 1914, was read and the Last Post was played by the buglers from the Last Post Association, followed by a Two Minute Silence. Wreaths were laid at the Tombstone of Corporal Albert Johannes Loubser. The Reveille followed. The National Anthem of the Republic of South Africa was sung by the learners of Hoerskool Waterkloof. Among the 50 people who attended the Remembrance was Ms Judith Nthere (Defence Office assistant) who accompanied Assistant Defence Attache Lt Col Andrew Mafofololo.

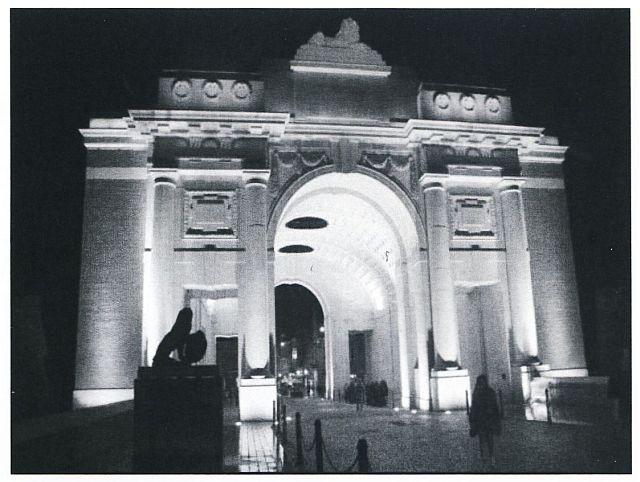

Menin Gate (Menin Poort) in Ypres

After supper, we went to Menin Gate. The cemeteries only tell part of the story of the Ypres Salient. For the rest, we must look to the great memorials to the missing, where 100 000 of the Commonwealth's dead, who have no known grave, are remembered by name. Eighty percent of the missing were killed in the Salient's major battles and, while many of their bodies were recovered after the war, more than half of them were lost without a trace. When the Imperial War Graves Commission considered how to commemorate the missing of the Ypres Salient, they soon realised that a single memorial would be insufficient and, in the end, five were needed. The largest of these is the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres itself, designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield. The Menin Gate is one of the best known Commonwealth memorials anywhere in the world; it sits astride the road along which hundreds of thousands of troops passed on their way to the front. The memorial commemorates more than 54 000 officers and men from South Africa, Canada, Australia, undivided India and those from the United Kingdom who died before 16 August 1917.

At the ceremony under the Menin Gate, wreaths commemorating the South African involvement were laid by Assistant Defence Attache, Lt Col Andrew Mafofololo, on behalf of the South African Government, and by Jason Hatting and Jani Heslinga from Hoerskool Waterkloof, Pretoria. The South African learners stood in a special position under the Menin Gate behind the buglers from the Last Post Association and had the honour to sing the National Anthem of South Africa under the Menin Gate, with more than 500 people attending. Since 1928, buglers from the Last Post Association have played the Last Post in this very spot every night at 8pm, with the exception of the years under German occupation during the Second World War. This takes place, irrespective of the number of attendants or the weather. The Last Post is played in honour of the soldiers of the British Commonwealth and all other Allied nations who died in the Ypres Salient during the First World War. It is a sound that haunts the listener, whether it inspires thought of military glory or of the futility of death in battle (Wilmott, 2012).

Reflections on War

Today, a century after the First World War, the citizens of Great Britain and countries like Australia, Canada and New Zealand continue to honour their dead. Each year, hundreds of coaches drive from one site to the other, with pilgrims getting off to lay flowers, plant flags and crosses in homage and then to continue with the trip. British school children are familiar visitors to the old battlefields, well-prepared for the occasion by their history teachers. While I was in Belgium there were at least weekly reports in newspapers and on television stations about the centenary commemorations of the different phases of the Battle of Passchendaele. Many countries devote resources to the commemoration of their fallen. President Jacob Zuma attended the 100-year South African commemoration at Delville Wood in 2016, but this was a rare visit. Much more can be done to remember our fallen during the Great War.

Acknowledgements

The learners and teachers wish to thank Mr Daan Potgieter, Headmaster of Hoërskool Waterkloof, the school's Governing Body and Marinda Behr for the opportunity to experience this exchange programme. Sint-Leo Hemelsdaele Secundaire School in Bruges and its teachers Filip Debergh and Annemie Vermeulen, and the parents and learners were wonderful hosts. A word of special thanks goes to Bonnie Joyce for her magnificent organisation during this exchange programme.

References

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org