The South African

The South African

At the end of 1944, there was hope that the war in Europe would soon be over and a 'Speed the Victory Cavalcade' was held at the Zoo Lake in Johannesburg. Plans were then already in place for a demobilisation scheme which would provide employment and sheltered employment for disabled soldiers, as well as loans and grants. The plan made provision for the interests of Coloured and Native soldiers, although they would be represented by Europeans. 'Discharged Soldiers and Demobilisation Committees' had been established and the aim was to have one in every town. Finding the means to repatriate POWs, servicemen and women to South Africa in the shortest time possible was now a priority.

The problem facing South Africa was that there would probably be a lack of shipping capacity to repatriate South African servicemen as shipping would be required to transport troops to the Far East. The only alternate was air transport and an accelerated Shuttle Service using all available Dakotas and Venturas was envisaged. The authorities along the route were informed of the intention of the South African Air Force (SAAF) to speed up the Shuttle Service between Rome and Pretoria in view of possible south-bound commitments to repatriate approximately 60 000 white servicemen, including Rhodesians. Five thousand per month would return by air and another 15 000 by sea in the second half of 1945 and hopefully 45 000 troops would be repatriated by the end of the year.

The Prime Minister, General Smuts, was informed and his response was: 'The return of troops to the Union at the end of Phase One (the War in Europe) is a matter of great public importance and urgency. Everything possible is to be done to get ready in the shortest possible time.'

The Royal Air Force (RAF) was informed of the increase in flights and advised the SAAF that the repatriation of South African servicemen did not come into what was known as the 'London Agreement' by which the SAAF could receive certain assistance from the RAF. The RAF made it known that certain facilities could be provided but not personnel and that the SAAF would be responsible for manning the staging posts and providing salvage parties along the route. It was further stressed that a method of accounting for services provided would have to be worked out.

The RAF offered to assist with Ventura spares and, to a lesser extent, with Dakota spares. The SAAF would have to use staging posts where it could make its own arrangements. All works required would have to be financed by South Africa. Fuel stocks would have to be built up along the route and this would mean an earliest starting date of 1 July 1945. Fuel supplies for Juba and Malakal would be dependant on how soon the Nile rose to allow the necessary fuel to be ferried to these airfields.

Staging posts

A survey of the route was conducted and discussions were held with all the authorities along the route concerning the various aspects that had to be resolved before detailed planning could commence. These included the provision of 24 hour signal and meteorological services, navigational aids, night flying facilities, flying control, transit refreshments, accommodation for servicing personnel and slip crews, flare paths on emergency landing grounds and refuelling. The lengths and state of runways had also to be confirmed.

The Union Defence Forces (UDF) had established 1 Reserve and Transit Depot at Helwan, south of Cairo. The camp was self-contained and could accommodate 5 000 in twenty blocks. Helwan was an asset in accommodating men arriving in Egypt and was therefore ideal for use during repatriation.

A choice had to be made regarding a new northern terminal of the Shuttle Service. The Helwan Airfield was nearest to the transit depot but the airfield itself was unsuitable for an accelerated Shuttle Service. Almaza Airfield at Cairo, the terminal of the Shuttle Service, was being handed back to the Egyptian authorities. Thus, Cairo West was chosen, even though it was two hours away by road from the transit Depot.

Use of the existing Shuttle Service staging posts was reviewed. The RAF planned to vacate Luxor and recommended that Wadi Haifa be used instead. The use of Khartoum had been ruled out as the US Army Air Force, which was manning the airfield, would be leaving and the airfield was being handed back to the Sudanese authorities. Tabora was chosen in preference to Dodomo which had been upgraded and extended by the SAAF in 1941 for use by the Shuttle Service.

Broken Hill was selected in preference to Ndola as it had a transit camp used earlier by the Shuttle Service to Nairobi. Also considered were the Belgium Congo airfields at Elizabethville and Kasama. As it turned out later, troops did not need to sleep over at staging posts and Ndola was used. The Bulawayo staging post was changed to Kumalo, which had adequate permanent buildings as it had been a flying school.

The plan

It would take four to five months to bring the troops back using both Dakotas and Venturas. The rough plan was to fly 25 aircraft a day, 50 passing through each staging post per day. By not having the troops stay over along the route, it was hoped to do a round trip in sixty hours.

Consideration was given to using the B-24 Liberator heavy bombers of 31 and 34 Squadrons to transport troops from Italy to Cairo and later to Kisumu. Negotiations took place with the USAAF and Sudanese authorities for the use of Wadi Seidna Airfield as a northern air terminal where the Dakotas from South Africa could meet up with the Liberators from Italy. The RAF agreed to provide additional Liberators and approved that they could be used as far south as Kisumu. They would be able to overfly Malakal and Juba, where the fuel situation was acute. However, it was doubtful if more than six Liberators a day could be sent to Kisumu as the runway there would be damaged by the Liberator's nose wheel on touchdown. There were also problems with handling the number of Liberators envisaged at Cairo West, but, with some development work, the airfield would be able to accommodate 24 Liberators a day.

A Liberator carried the same number of passengers as a Dakota at a higher speed, but used the equivalent fuel of six Dakotas. Director-General Air Force (DGAF) ruled against the use of the Liberator south of Cairo where supplies of fuel were problematic and restricted their use to flights between Italy and Cairo. Financial authority had been granted for the payment of the 57 Dakotas already allocated to the SAAF as well as for the purchase of an additional thirteen Dakotas and spare engines. Indents for spares had already been submitted to the RAF and directly to the supplying orgariisations in the United States.

Thirty-nine ex-USAAF Dakota Mark Is and one Mark II from the USAAF were offered to the SAAF, but the offer was turned down as the SAAF operated Dakota Marks IIIs and IVs. Curtis C46-60CK Commandos were available from India. This aircraft could carry 32 passengers as it had a centre row of seats. The instrumentation was the same as that fitted to the Dakota, but the greatest drawback was that it was fitted with different engines and Curtis Electric four-bladed propellers. A completely new maintenance organisation would have to be set up before the aircraft could be operated on the service. Of greater concern was the fact that no spare engines or propellers were available.

An agreement was reached with the RAF for thirteen of the Dakotas that had been operated by 28 Squadron at Maison Blanche to be made available to the SAAF. Another twelve were made available later.

Spares were also required for the Ventura aircraft. All the B-34 Venturas had been bought and paid for by the SAAF, while only nine PV-1 Venturas had been paid for. Of these nine, only five were available for use on the service. By May, the modifications to 35 Venturas to enable them to carry fourteen passengers was halfway complete and another twenty were awaiting modifications. Consideration was given to stripping the camouflage from the aircraft as the saving in weight would provide extra payload.

'Intensified Transport Service'

At a meeting held on 4 April 1945, the name 'Intensified Transport Service' (ITS) was approved for the service. DGAF advised Chief of General Staff (CGS) that the proposal was feasible and that it would entail a formidable organisation to carry out the repatriation over a period of four to five months. He stressed that its success was dependent on the remainder of the allocated Dakotas, thirteen additional Dakotas and essential spares being delivered on time for the start of the service.

OPERATION PUNCH had been a good trial run for the planned ITS. It had entailed the movement of 600 troops to Rome by 5 Wing as reinforcements for the 6th South African Armoured Division. It showed that it was possible to accelerate the shuttle by using slip crews, thus reducing the requirement for night stops.

The begin date for the plan was set for 1 July 1945. The final plan was endorsed by General Smuts who advised Treasury that the scheme was of a high priority and, providing that it was not too extravagant, he wished it to be pursued. Financial authority to proceed with the ITS was received on 9 April.

A new organisation and additional infrastructure along the route was required. To control the ITS, 4 Group was formed. Under it would fall 5 Wing, operating Dakotas from Zwartkop, and 10 Wing, still to be established, operating Venturas from Pietersburg. Pietersburg had been used by 26 Air School which had been disbanded in December 1944. The detachments established at the staging posts would also fall under 4 Group and arrangements had to be made for facilities along the route.

As far as signals were concerned, it was decided to join the RAF scheme that was entirely independent of the Civil Authorities. This scheme was essentially the same as that used by the SAAF and provided day and night frequencies. There was little that could be done to counter the malaria risk, other than to apply normal protective measures which would include spraying, personal precautions and general anti-malarial discipline. A medical officer and additional medical staff would be based at each staging post. Not having the troops stay over along the route would also assist in avoiding outbreaks of malaria. Semi-permanent accommodation was planned for permanent staff and slip crews and a minimum of amenity buildings would be provided for troops in transit.

The minimum acceptable length of a runway was 2 000 metres and runways had to have concrete tips at each end. This meant that work would have to be done at Tabora and Juba. Work at airfields was prioritised, runways and taxiways having the highest priority, followed by hardstandings, petrol installations and technical accommodation.

Each staging post needed a 24-hour signal and meteorological service. To accommodate the ITS as a 24-hour service, night flying facilities and navigation aids were needed on certain sectors. At Kisumu, a double flare path and approach funnel with obstruction lights on surrounding hills was required. Elsewhere, gooseneck flares would do, with two sets of glide indicators. An order was placed for the fuel required for a four month period along the entire route.

Staging Post Detachments were established at Kumalo, N'Changa (Ndola), Tabora, Kisumu, Juba, Malakal, Wadi Seidna, Wadi Haifa and Cairo West. They were numbered from 1 to 9 respectively. The number of personnel required at each staging post was: 57 ground crew, 7 refuellers, 30 signallers, 6 meteorologists and 20 headquarters administrative staff, a total of 120 members per detachment. One hundred maintenance personnel were based at Cairo West and the headquarters staff there was increased to 50. At Kisumu, 220 slip crew members would be based, and at Cairo, 110. Of the 4 500 members of 4 Group, nearly half would be stationed along the route.

10 Wing

At the beginning of May, a start was made on establishing 10 Wing. The nucleus of 10 Wing would be formed by 29 Squadron and personnel would be used from 26 Squadron, which had returned to the Union from Takoradi, as well as personnel from 3 Air Depot, which was in the process of disbanding. A Ventura Transport pilots' training unit was established at 27 Air School, based at Bloemspruit. The first course started in the middle of April with 34 pilots and lasted six weeks.

Arrangements were made to take over 15 Air Depot at Pietersburg. The move of 29 Squadron from Mtubatuba to Pietersburg and the handover of the camp to 10 Wing took place on 4 June. The first of 10 Wing's B-34 Venturas arrived on 11 June and two Harvards were made available for Met flights. An Anson was also made available. Two aircraft left for Cairo to ferry personnel and equipment required on the northern section of the route and personnel from 11 Operational Training Unit (OTU) arrived from Reunion, Durban. The two aircraft that would be used to position slip crews were sent to Kisumu and Cairo before the service started on 1 July. One of them force-landed near Lusaka on the way north when it ran out of fuel. A replacement aircraft was sent to continue with the flight. On 18 June, a large influx of aircrew from 23 Squadron and the Ventura Transport Training Unit arrived and the next day the rear party from 29 Squadron arrived. Converted Venturas were collected from Zwartkop, bringing the total on strength to 27 by the end of June. The Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) camp was completed; sports clubs, messes and a library were established before the start of the service.

5 Wing

Meanwhile, 5 Wing continued to operate the Shuttle Service to Cairo and Europe. The number of aircraft operating per day during May had increased to four. During the month, 61 of the 86 flights flown went to the United Kingdom, carrying POWs from Italy. In June, the number of flights flown to Cairo increased gradually to seven a day on 18 June. A 5 Wing crew flew a PV-1 to Takoradi with crews to collect three newly delivered Dakotas, which they then flew to Cairo to uplift spares. During a short period from 29 May to 9 June 5 Wing transported South African POWs from the UK to Cairo. Only seventeen flights were flown during this task.

The launch of the accelerated Shuttle Service

The ITS started from Pietersburg as planned on 1 July with the departure of two aircraft. By the middle of the month, six Venturas left for Cairo per day, taking off at tenminute intervals. On 18 July, a Ventura crashed on landing at Khartoum and its crew of three and thirteen passengers were killed. Subsequent to the accident, a policy was drawn up requiring every commander to have a total of 1 000 hours, with at least 50 hours on a Ventura. Co-pilots would be carried and, until dual controls were fitted, they would accompany flights to gain route experience. Due to the new qualifications that were required by commanders, it was impossible to reach the objective of 250 crews. Intensified training began, to build up Ventura hours for commanders to qualify. Three-hour cross-country flights by day and one to two-hour cross-country night flights were flown. These flights also gave newly qualified navigators experience in map reading. A film was made of the approaches to the airfields on the route to assist in familiarising crews.

By the end of August, there were 63 Venturas, two Ansons and two Harvards on the strength of 10 Wing. A flow of three aircraft a day was maintained, with 95 flights leaving during the month. There were now 56 commanders, but only 50 co-pilots. The shortage of co-pilots resulted in three aircraft leaving on 18 August without a co-pilot.

The average round trip time for a trip was reduced to eleven days using the slip crews, during which, when allowance was made for compass swings and training, pilots had only two days off between flights. There was a surplus of navigators and wireless operators, some of whom were released from service.

Helwan

With the ending of the war in Europe, it was made known through The Springbok, the UDF newspaper distributed free from Cairo to all South Africans, that repatriation proper would begin on 1 July 1945. There were, at that stage, 2 500 troops at Helwan awaiting repatriation. This number, until the end of June, could only be reduced by eight per day, the number of seats allocated to land force units while 40 seats were allocated to the air force. During July, the land forces' allocation would increase to 160, but no commitment was given on the daily amount for August and beyond. To be able to use shipping made available at short notice there would be a limited pool of servicemen awaiting repatriation in the Middle East.

On 9 August, it was announced that 3 000 to 5 000 troops could be repatriated by sea and the Foggia Transit Depot, similar to Helwan, lost no time in sending a shipload to Egypt. They were already on their way when, on 15 August, it was announced that the expected shipping had been delayed. Helwan could accommodate 5 000 but was now holding 9 000, with 40 to 50 in a room designed to accommodate 25. The perception at the end of May that 500 men would be repatriated by air per day had not materialised.

Overcrowding and unbearable camp conditions resulted in an incident that has seldom been included in writings on the history of the UDF. On the night of 20 August 1945, South Africans went on the rampage at Helwan, burning down two cinemas, preventing the fire brigade from extinguishing the fires, looting Egyptian premises and setting alight shops, cars and book stalls. They also set alight a mess and NAAFI liquor store.

The General Officer Commanding 6th South African Armoured Division flew in from Italy to address the troops, promising that steps were being taken immediately to speed up the rate of repatriation. The court of enquiry findings spoke of the frustration and despondency felt by the troops at not being repatriated as quickly as they had believed they would be and of the overcrowding at Helwan. It recognised the low standard of messing, the dispirited state of mind of those coming from Foggia, and the high charges asked by the Egyptians, who had exclusive trading rights in the camp.

There was a serious shortage of fuel at Juba in September, holding up departure for three days and leaving seventeen aircraft congested on the airfield until fuel from Kisumu and Malakal was ferried in by two Dakotas. The departures from Pietersburg were also delayed for three days to allow the congestion on the route to clear.

Review

The Intensified Shuttle Service was reviewed and it became increasingly apparent that 10 Wing would not be able to carry on much longer. On its way south was 28 Squadron with 25 Dakotas that would be taken over by 5 Wing, while Sunderlands of 35 Squadron were being prepared to carry passengers. The Ventura Pilots Training Unit at Bloemspruit closed on 1 October. During October, personnel were posted out to assist 5 Wing, or discharged or released from service. Sections had to be closed down and personnel misemployed to keep 10 Wing functioning. The two servicing flights and the maintenance section were amalgamated.

On 31 October the civil airport was handed back to the Pietersburg Municipality with the wing retaining the responsibility for the meteorological station as well as guarding the Aeradio station and emergency landing ground at Papkuil. The navigation, intelligence and signals sections were closed by the end of October. The last aircraft left on 31 October and all aircraft on the route were expected back by 15 November.

In November, 15 Air Depot took over the responsibilities of 10 Wing at Pietersburg and a detachment was established. It was responsible for the Meteorological Flight of Harvards, the guards at the auxiliary landing grounds, the Signal Station and the Meteorological office at the Civil Aerodrome. The detachment remained at Pietersburg until 21 August 1946, when it moved to Snake Valley and was re-designated as 15 Reserve Aircraft Storage Depot.

2 Wing

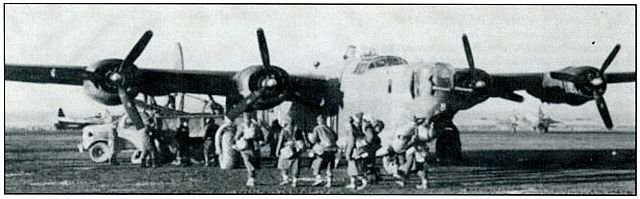

With the cessation of hostilities in Italy, Liberators of 2 Wing's 31 and 34 Squadrons were being used to carry supplies. Towards the middle of May 1945, this gradually gave way to transporting army personnel. Large numbers of Allied POWs were arriving in Italy for repatriation to the United Kingdom and, owing to limited shipping facilities and the desire to hasten their return home, it was decided that the journey from Italy to UK would be carried out by air. This commitment was allocated to RAF 205 Heavy Bomber Group, under whose control 2 Wing resorted.

To minimise the risk of accident, only experienced crews were permitted to participate in the airlift. Pilots chosen had to have at least 600 flying hours to their credit of which 50 hours had been on Liberators, or a total of 500 flying hours experience of which 100 hours had been on Liberators. Each crew was required to carry out a familiarisation flight to England and the first of these left Foggia on 10 May. Six days later the first Liberator carrying POWs took off for England. The British POWs were lifted from airfields at Bari and Naples and delivered to Westcott Airfield in Buckinghamshire. To enable their efforts to be stepped up, the number of Liberators allocated to the two SAAF squadrons was increased to 24. These flights were terminated in June.

Towards the end of May, a further assignment was given to 2 Wing, that of transporting 6th Division troops and SAAF members from Italy to Cairo. On 26 May, 150 6th SA Armoured Division members emplaned at Foggia, bound for Cairo on the first stage of their journey back home. A Liberator carried 25 servicemen and, on the return flights from Cairo, the Liberators carried Greek soldiers who disembarked at Hassani Airfield near Athens. English soldiers were taken aboard and flown as far as Foggia on their journey back to the UK.

During August plans were made for 31 and 34 Squadrons to move to the Middle East. An advance party left by air on 13 September, while the main party sailed on the Carnarvon Castle. At the time, 2 Wing was based at the RAF Air Station at Shallufa, situated quite close to Suez. Operating from Shallufa, the Liberators continued transporting army and SAAF personnel from Italy to the Middle East, returning via Greece.

The days of 2 Wing and the squadrons were numbered. The RAF took over the aircraft and flew them back to the UK on the expiry of their permissible life of 500 flying hours. At the beginning of October, plans were made to repatriate 2 Wing and its final parade took place on 7 December. Most members had left by 12 December, although some only left Cairo at the end of the month.

The two heavy bomber squadrons had made a significant contribution to the repatriation of servicemen and POWs. To maintain this extraordinary effort, the ground crews had to work day and night. At times it was difficult for them to believe that the war was over as they were of the opinion that peace entailed a greater effort than war.

The Sunderland

South Africa's 35 Squadron had been formed from 262 Squadron RAF on 15 February 1945. The squadron's role was the protection of South African waters from the overt German U-Boat threat. The RAF had made a gift to South Africa of twelve Sunderlands and South Africa had purchased another three. The Squadron was still very much in its infancy when hostilities ended in Europe. The war in the Far East was expected to be protracted and there was an urgency to get 35 Squadron converted onto the Sunderland for deployment to the Far East. By the time Japan surrendered, a full complement of crews was trained and ready for deployment.

With the war over and little need for the recently trained crews, a proposal was made to use the Sunderlands on the ITS. Details of seating, the distribution of weights and a provisional route had already been worked out by 35 Squadron. Discussions were held with BOAC on facilities along the route as it had operated flying boats down the East Coast of Africa to Congella at Durban throughout the war. A survey flight was flown at the beginning of September. The first stop was at Lindi, which was found only to be suitable as an emergency stop. The next stop was Kisumu on Lake Victoria, which proved to be an exceptional night stop with superior maintenance facilities. The flight continued to Cairo via Khartoum, both times landing at BOAC facilities on the Nile. There was a suitable transit camp at Kasfreet in Cairo, which would provide all the necessary accommodation. On the return flight the aircraft landed at Mombasa.

The route decided on from Cairo to Durban was via Khartoum, Kisumu, Beria, Mombasa, Beira, with Dar es Salaam and Lindi as emergency stops. Beria would only be used as a refuelling stop, with night stops at all the other points alternating between north and south-bound aircraft.

By the end of October, all armament had been removed from the Sunderlands and 42 seats installed. Provision was made for meals to be served on board and a smoking compartment was provided. A further survey flight took place at the end of October and the first flight left for Cairo on 2 November 1945 and arrived back at Durban on 13 November. A courtesy stop was made at Luxor on the north-bound route to accommodate RAF needs. The Sunderland carried 40 male passengers, south-bound, with a kit limitation of 40 pounds (just over 18 kg). The crews stayed at RAF bases in Mombasa and Kisumu and at the Riverside Camp in Khartoum. Servicing detachments to support the flights were established at Beira, Mombasa, Kisumu, Khartoum and Kasfreet.

The use of the Sunderland was justified. It carried 40 passengers compared to 13 of the Ventura and it made fewer stops because of its range. After the withdrawal of 10 Wing's Venturas, the Dakotas bore the brunt of the work on the Intensified Transport Service. By February 1946 the Sunderland flights had dropped to every third day. The last Sunderland flight left Cairo on 2 March with Major-General Everard Poole of the 6th South African Armoured Division and his staff as passengers. All detachment personnel were returned by the end of March 1946.

The Sunderlands brought home 2 081 personnel and carried some 50 tons of freight. At no stage was a shuttle more than a day late. One aircraft was delayed at Kisumu for fifteen days but the reserve aircraft took its place. Many members of 35 Squadron, who had stayed on for the Intensified Transport Service, were released from service.

Concluding the service

The last of 25 Dakotas flown back by 28 Squadron arrived on 8 October 1945. The crews were sent on fourteen days' leave, ready to start with the ITS in November. As the extra Dakotas became available, they replaced the Venturas of 10 Wing. On 22 October 1945, 5 Wing was disbanded and 4 Group took over the direct control of the ITS aircraft.

Early in February 1946 it was anticipated that the ITS would be concluded by 31 March 1946. The intention was to replace it with a skeleton Shuttle Service of one aircraft a day, according to requirements, with the assistance of the RAF and petrol companies for refuelling. As the service would not require an organisation like 4 Group to control it, 28 Squadron would be allocated between ten and twelve Dakotas and given the responsibility of running the service. Personnel would have to be earmarked for 28 Squadron and 4 Group was to commence with clearing its personnel from the route and winding itself up.

On 7 March, 4 Group ceased operations and was disbanded. On 18 April 1946, 28 Squadron was re-formed as a Permanent Force unit at Zwartkop. A Board of Survey arranged for the return of equipment loaned from local sources or supplied by the RAF. It decided on what equipment and vehicles should be returned to the Union or disposed of by local sales or reduced to produce. Liabilities that arose through the use of property and fixed installations were settled and contracts terminated. The last of the outstanding payments for the ITS was made in 1952.

Every effort was made to allay fears of flying amongst the returning soldiers. They had lost a well respected leader, Dan Pienaar, in an air crash and had heard of other crashes. A booklet was given to every passenger and covered rules for the flight and demobilisation schemes. It began with: 'This adventure of flying from Cairo to Pretoria will, no doubt, take a high priority in our memories of World War Two. It is an experience for which fat businessmen and the wealthy ones of South Africa paid more than £200 before the war. You are getting it for "baksheesh", not because the UDF is a magnanimous institution, but because, frankly, it is the quickest way to get us all home. At the same time, the UDF chiefs are very happy that thousands of men will be experiencing for the first time, the thrill of speedy travel by air. We have entered a new transport age and, after this trip to South Africa, we should all be so air conscious that the time will come when we will board an aircraft with the same nonchalance as we do a tram, or train, or a ship today.'

The travelogue prepared by 10 Wing for navigators briefing passengers on the shuttle service was more to the point: 'The great majority of your passengers will be flying for the first time. They will be suspicious of aircraft in general and Venturas in particular. Many of them will be suffering from that chronic army complaint - Airforcephobia. They will have heard vaguely of gremlins and they will have a sneaking belief that you, your pilot and wireless operator are, in fact, gremlins in uniform. It is your job to dispel all these suspicions and false beliefs. Flying is not repeat not - a dangerous way of travelling. But don't introduce the subject of danger. If your passengers start discussion on the subject, you can easily defeat their arguments by pointing out that a comparison of road accident figures with present day flying accident figures shows that many more people are written-off by cars than by aircraft. If, after all this display of intelligence on your part, they are still under the impression that the air force is peopled by thinly disguised gremlins, admit quite frankly that we are ordinary (very ordinary - most of us) human beings with a variety of civil occupations and no further round the bend than anyone else in Khaki.'

On arrival in South Africa volunteers from the South African Women's Auxiliary Service (SAWAS) were on hand with refreshments and POWs were met by the POW Relatives Association.

There have been many tales told of the ITS, some of which have been published. One of the most interesting of these was of crew members who took tea to Egypt. If the customs officials were present to meet the aircraft, a message would be sent to advise the crew that 'the sands are rising' and the tea would be jettisoned. It was rumoured that when Dakotas were taken out of storage at 15 Air Depot for conversion to navigation trainers in the late 1950s, tea leaves were found in large quantities under the floor boards!

The ITS achieved its purpose in the eight months of its existence and was at that time the biggest airlift in Africa.

Acknowledgements

The late A V Weinerlein for copies of Africa Star and Springbok newspapers.

References

10 Wing War Diary, June to December 1945

SAAF Museum Swartkop Research Centre

SANDF Documentation Services

Bibliography

Cryws-Williams, J et al, A Country at War (Ashanti Publishing, Rivonia,1992).

Isemonger, L, The Men who went to Warsaw (Freeworld Publications, Nelspruit, 2002).

Joyce, P, et al, World War 11 1939-1945 (The Star, Johannesburg, 1989).

Spring, I R D, Flying Boat (Spring Air, Johannesburg, 1995).

Webster, S, 'The Helwan Riots' in Military History Journal, Volume 12 No 3, June 2002.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org